- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- Contemporary

- Security & Defense

- Terrorism

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- History

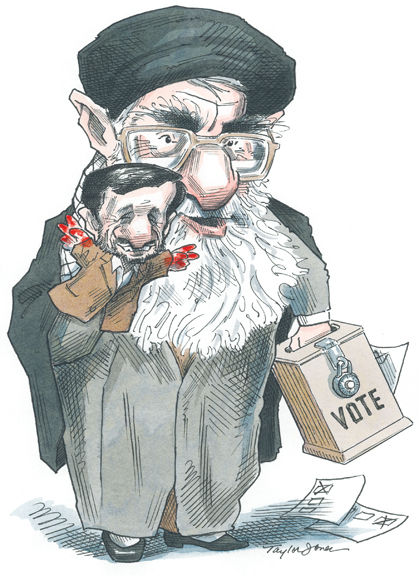

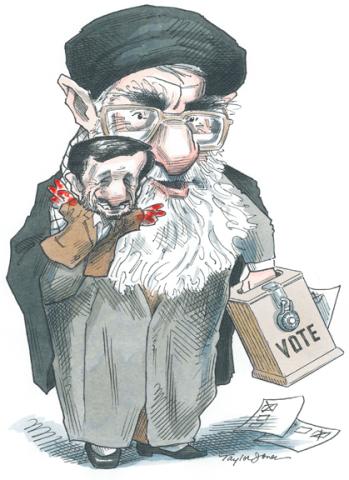

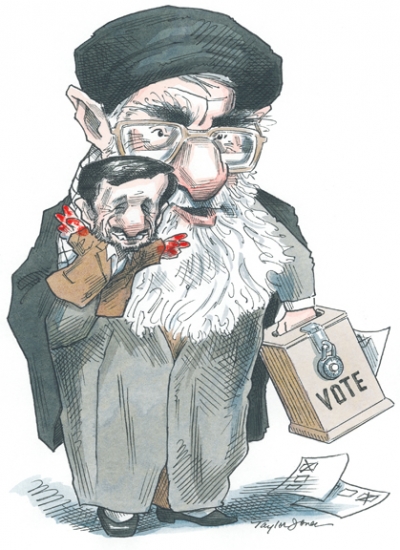

Last summer, in the most anticipated speech of his storied career, Ali- Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani finally weighed in on the side of the opposition in Iran’s postelection crisis. Whereas Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and his despotic cohorts praised June’s presidential election as “blessed” and divine, the “freest in the world,” and the “death knell of liberal democracy in the world,” former president and parliament speaker Rafsanjani declared it incurably flawed and the source of a “crisis of confidence” in the nation. It is, he said in a defiant July 17 speech, un-Islamic to “ignore people’s votes,” bluntly accusing the regime of stealing the election. He demanded the release of all political prisoners, saying they must be allowed to offer their services to the nation. And he began his Friday sermon by conjuring the name of Ayatollah Mahmoud Taleghani—easily the most democratic cleric of the early days of the revolution and the man, not incidentally, who edited the new version of Ayatollah Mohammed Hussein Naini’s famous twentieth-century treatise on the necessity of democracy for Shiite countries.

In nearly every one of these defiant declarations, Rafsanjani took aim at Khamenei, once again reaffirming that the days of Khamenei as the infallible spiritual leader have mercifully ended.

It is increasingly clear that the opposition protests that continue to simmer in Iran have seriously undermined the credibility of the regime. Four of Iran’s highest-ranking ayatollahs have issued statements defiantly declaring the current regime “illegitimate.” Iranian Nobel Peace Prize laureate Shirin Ebadi has asked the international community to refuse to negotiate with the Ahmadinejad presidency until the crackdown on the opposition ends. And two of the most important groups within the Shiite clerical establishment—Majma Rohaniyat-e Mobarez and Majma Moddaresin o Mohaggegin Hozeye Elmiye Qom—have issued statements doubting the legitimacy of the election.

But Mahmoud Ahmadinejad lives in a parallel universe peopled by corrupt sycophants whose continued presence at the trough of public funds is dependent on his continued presidency. He is as willfully ignorant of the sentiments of Iranian society as of the realities of the modern world. He talks constantly of his desire to help the world’s poor and dispossessed and expedite the return of Shiism’s hidden imam. Although Ahmadinejad will probably be even more deluded during his second term, the changing domestic and international dynamics will, it is hoped, force him back to reality.

AIR OF INVINCIBILITY SHATTERED

Ahmadinejad’s domestic agenda was previewed during a meeting in June with his spiritual guru, Mohammad Taghi Mesbah-Yazdi, who is notorious not only for providing the theological underpinnings of Ahmadinejad’s messianic fervor but also for fueling his disdain for liberal democracy. Mesbah-Yazdi rejects all things Western: to him, elections and parliaments are silly Western paraphernalia; even the name of the country—the Islamic Republic of Iran—to him reflects liberal appeasement. Laying out the plans for his second term, Ahmadinejad promised his spiritual guru a full implementation of Islamic values throughout Iran’s educational and cultural system. Iranians have hitherto had nothing like “true Islam,” he said; as soon as people “get a whiff ” of this genuine faith, they will rush to embrace it.

If the attempt at an Islamic cultural revolution undertaken by the regime in the 1980s is any indication, Ahmadinejad’s promised “Islamization” of society can only be realized by a massive purge of the educational system and by far more drastic censorship in the cultural domain. Many of the more traditional members of the Islamic elite (particularly Rafsanjani, who faced intense public pressure from Khamenei and his allies to break Rafsanjani’s alliance with the reformists) will face serious challenges to their authority; some might even face jail sentences.

At the same time, Ahmadinejad is likely to continue the process of enriching commanders of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and members of the paramilitary Basij forces—as he did during his first four years in office. Four years ago, he ran on a populist economic platform that promised to fight corruption and put a bigger slice of the oil pie on each plate. He ran this year on the same platform, despite the fact that he had surrounded himself by many IRGC commanders notorious for corruption—foremost among them being Sadeq Mahsuli, the interior minister in charge of the elections. And it seems that few, if any, of those accused of corruption have served a day in prison.

In addition, as many reformists have warned, the republican elements of the 1979 constitution are in serious jeopardy. Ahmadinejad has more than once hinted at his wish to follow in the footsteps of Venezuelan leader Hugo Chávez by changing the constitution and becoming a lifetime president. Today, hundreds of Ahmadinejad’s emissaries are in Venezuela working with the Chávez government. There are reports of close cooperation between the two countries’ intelligence agencies, particularly on methods of crowd and opposition control, as well as plans to co-opt the lower classes through patronage. The Ahmadinejad-Chávez relationship is not surprising, considering the many similarities between their brands of populism, including election-rigging methods and government-sanctioned anti-Semitism.

Several things, however, work against the implementation of those shared plans. Iranian society now recognizes the power of its own civil disobedience. The two supposedly losing candidates in the June voting, Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karubi, show no sign of cracking under increasing pressure to accept defeat. The youth—written off until recently by most scholars and analysts as incorrigibly sybaritic, self-centered, and apolitical—have shown remarkable resilience and courage in asserting their rights. The regime’s air of invincibility has been shattered, and it will no longer be able to rule without regard to public will.

In international politics, Ahmadinejad can be expected to be even more publicly confrontational. As Mousavi has suggested, Ahmadinejad’s overseas saber-rattling will be a thinly veiled attempt to garner internationally the respect he so clearly lacks at home. The heart-wrenching pictures of brutality on Iranian streets broadcast over international media have convinced more and more people that the regime cannot be trusted with a bomb. But it is highly unlikely that he will publicly compromise on the nuclear issue: today, the regime, ever more bereft of legitimacy at home and abroad, cannot seem to be compromising on the nuclear issue. More than ever, it needs to claim a victory—and continuing some level of uranium enrichment is mandatory.

PRESSURE, WEAKENING INFLUENCE

But the regime’s desperate economic situation—the need to create about a million jobs a year just to keep unemployment at the same level as today and to invest billions of dollars in the country’s failing oil infrastructure— will inevitably force it to seek rapprochement with the West in general and with the United States in particular. There are already signs that the Islamic Republic is losing much of its influence in the Muslim world. The Iranianbacked Hezbollah lost the recent election in Lebanon, and there are hints that Hamas might be inching toward an alliance with the Palestinian Authority. Some radical Sunni groups, such as the Muslim Brotherhood, who had earlier been flirting with Iran, are now voicing criticism of Iran’s flawed election.

Perhaps most significant, the regime’s Shiite allies in Iraq are also distancing themselves from their Persian patrons. A few weeks before the Iranian election, Rafsanjani made a trip to Iraq in which he met with Ayatollah Ali Sistani, an Iranian-born cleric who is the highest-ranking Shiite figure in the world; in a subsequent official statement, the Iraqbased cleric emphasized how important it was that voices of moderation like Rafsanjani’s retain their power. The comment was clearly meant as a warning to Ahmadinejad and other members of the regime, who had been using increasingly tough language against Rafsanjani (even jailing his daughter briefly). Sistani’s refusal to publicly support the Iranian regime was only the most evident sign of a rift that has long existed between his brand of Shiism and the kind promulgated by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomenei and now followed by Khamenei. The Iranian regime’s weakening influence across the region—particularly in Iraq, where it holds the most leverage over U.S. interests—will force it to be more pragmatic in its international dealings.

Ahmadinejad, buoyed by support from Khamenei and the IRGC, will still have a relatively strong hand heading into his second term. But the continued defiance of the Iranian people and an increasing number of the Islamic elite, dire economic realities, and a rising chorus of criticism from democracies all around the world make it highly unlikely that Ahmadinejad will be able to ignore reality for long.