- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

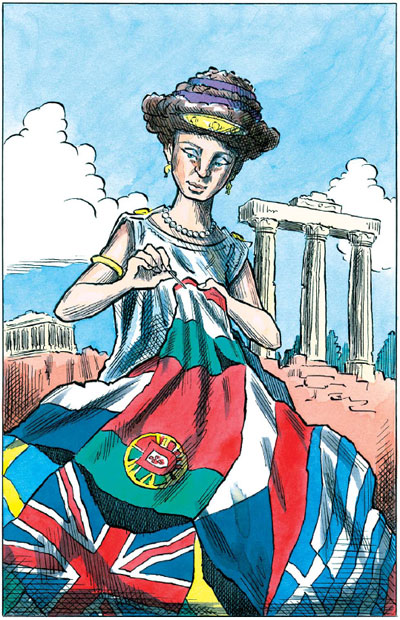

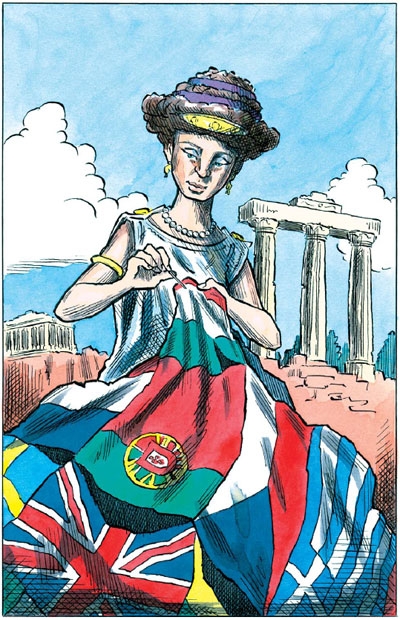

Europe has lost the plot. As we look back at the March 25 anniversary of the Treaty of Rome—the 50th birthday of the European Economic Community that became the European Union—Europe no longer knows what story it wants to tell. A shared political narrative sustained the postwar project of (Western) European integration for three generations, but it has fallen apart since the end of the Cold War. Most Europeans now have little idea where we’re coming from; far less do we share a vision of where we want to go to. We don’t know why we have an EU or what it’s good for. So we urgently need a new narrative.

I propose that our new story should be woven from six strands, each of which represents a shared European goal. The strands are freedom, peace, law, prosperity, diversity, and solidarity. None of these goals is unique to Europe, but most Europeans would agree that it is characteristic of contemporary Europe to aspire to them. Our performance, however, often falls a long way short of our aspirations. That falling short is itself part of our new story and must be spelled out. For today’s Europe should also have a capacity for constant self-criticism.

In this proposal, our identity will not be constructed in the fashion of the historic European nation, once humorously defined as a group of people united by a common hatred of their neighbors and a shared misunderstanding of their past. We should not even attempt to retell European history as the kind of teleological mythology characteristic of nineteenth-century nation building. No good will come of such a mythopoeic falsification of our history (“from Charlemagne to the euro”), and it won’t work, anyway. The nation was brilliantly defined by the historian Ernest Renan as a community of shared memory and shared forgetting, but what one nation wishes to forget, another wishes to remember. The more nations there are in the EU, the more diverse the family of national memories, the more difficult it is to construct shared myths about a common past.

Nor should our sense of European togetherness be achieved by negative stereotyping of an enemy or “other” (in the jargon of identity studies), as Britishness, for example, was constructed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in contrast to a stereotyped France. Since the collapse of the Soviet communist “East,” against which Western Europe defined itself from the late 1940s until 1989, some politicians and intellectuals have attempted to find Europe’s “other” in either the United States or Islam. These attempts are foolish and self-defeating. They divide Europeans rather than uniting them. Both the negative stereotyping of others and the mythmaking about our own collective past are typical of what I call Euronationalism: an attempt to replicate nationalist methods of building political identity at the European level.

In this proposal, Europe’s only defining “other” is its own previous self: more specifically, the unhappy, self-destructive, at times downright barbaric chapters in the history of European civilization. With the wars of the Yugoslav succession and the attempted genocide in Kosovo, that unhappy history stretches into the very last year of the past century. This is no distant past. Historical knowledge and consciousness play a vital role here, but it must be honest history, showing all the wrinkles, not mythistoire.

By contrast with much traditional EU-ropean discourse, neither unity nor power is treated here as a defining goal of the European project. Unity, whether national or continental, is not an end in itself, merely a means to higher ends. So is power. The EU does need more capacity to project its power, especially in foreign policy, so as to protect our interests and realize some benign goals. But to regard European power, l’Europe puissance, as an end in itself, or desirable simply to match the power of the United States, is Euronationalism, not European patriotism.

So our new narrative must be an honest, self-critical account of progress (very imperfect progress but progress nonetheless) from different pasts toward shared goals that could constitute a common future. By their nature, these goals cannot fully be attained (there is no perfect peace or freedom, on earth at least), but a shared striving toward them can itself bind together a political community.

What follows are notes toward the formulation of such a story, with built-in criticism. This is a rough first draft, for others to criticize and rework.

Freedom

Europe’s history over the past 65 years is a story of the spread of freedom. In 1942, there were only four perilously free countries in Europe: Britain, Switzerland, Sweden, and Ireland. By 1962, most of Western Europe was free, except Spain and Portugal. In 1982, the Iberian Peninsula had joined the free, as had Greece, but most of what we then called Eastern Europe was under communist dictatorship. Today, among countries that may definitely be accounted European, only one nasty little authoritarian regime is left—Belarus. Most Europeans now live in liberal democracies.

That has never before been the case, not in 2,500 years. And it’s worth celebrating. A majority of the EU’s current member states were dictatorships within living memory. Italy’s president, Giorgio Napolitano, has a vivid recollection of Mussolini’s fascist regime. The president of the European commission, José Manuel Barroso, grew up under Salazar’s dictatorship in Portugal. The EU’s foreign policy chief, Javier Solana, remembers dodging General Franco’s police. Eleven of the 27 heads of government who gathered round the table at the spring European council, including Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany, were subjects of communist dictatorships less than 20 years ago. They know what freedom is because they know what unfreedom is.

To be sure, people living under dictatorships wanted to be free mainly because they wanted to be free, not because they wanted to be EU-ropean. But the prospect of joining what is now the EU has encouraged country after country, from Spain and Portugal 30 years ago to Croatia and Turkey today, to transform its domestic politics, economy, law, media, and society. The EU is one of the most successful engines of peaceful regime change ever. For decades, the struggle for freedom and what is emotively called the “return to Europe” have gone arm in arm.

Shortcomings: Closer examination shows that many of Europe’s newer democracies are seriously flawed, with high levels of corruption—especially, but by no means only, in southeastern Europe. Money also speaks too loudly in the politics, legal systems, and media of our established democracies, as it does in the United States. Whatever the theory, in practice rich Europeans are more free than poor ones. The EU is a great catalyst of democracy, but it is not itself very democratic. EU regulations are justified in the name of the Treaty of Rome’s “four freedoms,” the free movement of goods, people, services, and capital—but these regulations can themselves be infringements of individual freedom. Anyway, the EU can’t claim all the credit: the United States, NATO, and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe have also played a major part in securing Europeans’ freedoms. Until recently, the defense of individual human rights and civil liberties had been more the province of the Council of Europe and its European court of human rights than of the EU.

Peace

For centuries, Europe was a theater of war. Now it is a theater of peace. Instead of trying out our national strengths on the battlefield, we do it on the soccer field. Disputes between European nations are resolved in endless negotiations in Brussels, not by armed conflict. The EU is a system of permanent, institutionalized conflict resolution. If you get tired of Belgian waffle and fudge, contemplate the alternative. It may seem to you unthinkable that French and Germans would ever fight each other again, but Serbs and Albanians were killing each other only the day before yesterday.

You cannot simply rely on goodwill to keep the peace in Europe. This may be an old, familiar argument for European integration, but that does not make it less true. Sometimes the old arguments are still the best.

Shortcomings: We cannot prove that it was European integration that kept the peace in Western Europe after 1945. Others claim it was NATO and the hegemonic system of the Cold War, with the United States functioning as “Europe’s pacifier”; still others cite the fact that Western Europe became a zone of liberal democracies and liberal democracies don’t go to war with each other. Several things happened at once, and historians can argue about their relative weight. Anyway, Central and Eastern Europe did not live at peace after 1945: witness the Soviet tanks rolling into East Berlin, Budapest, and Prague and the “state of war” declared in Poland in 1981.

Moreover, Europe—in the sense of the EU and, more broadly, the established democracies of Europe—failed to prevent war returning to the continent after the end of the Cold War. Twice it took U.S. intervention to stop war in the Balkans. So what are we so proud of?

Law

Most Europeans, most of the time, live under the rule of law. We enjoy codified human and civil rights, and we can go to court to protect those rights. If we don’t receive satisfaction in local and national courts, we have recourse to European ones—including the European court of human rights. Men and women, rich and poor, black and white, heterosexual and homosexual, are equal before the law. By and large, we can assume that the police are there to defend us, rather than advancing the interests of those in power, doing the bidding of the local mafia, or lining their own pockets.

We forget how unusual this is. For most of European history, most Europeans did not live under the rule of law. At least two-thirds of humankind still does not today. “I have a gun, so I decide what the law is,” an African officer at a roadblock told a journalist of my acquaintance, before pocketing an arbitrary “fine.”

The EU is a community of law. The Treaty of Rome and succeeding treaties have been turned into a kind of constitution by the work of European courts. One scholar has described the European Court of Justice as “the most effective supranational judicial body in the history of the world.” EU law takes priority over national law. Even the strongest governments and corporations must eventually yield to the rulings of European judges. Why are the leading European soccer teams full of players from other countries? Because of a 1995 ruling by the Court of Justice. It is thanks to the judicial enforcement of European laws on the four freedoms that most Europeans can now travel, shop, live, and work wherever they like in most of Europe.

Shortcomings: In practice, some are more equal than others. Look at Silvio Berlusconi. And there are still large areas of lawlessness, especially in eastern and southeastern Europe. In established democracies, security powers, including detention without trial, have been stepped up, violating civil liberties in the name of the “war on terror.” And the primacy of European law and the power of judges is, of course, precisely what Euroskeptics—especially in Britain—hate. They see it as stripping power from the democratically elected parliaments of sovereign states.

Prosperity

Most Europeans are better off than their parents and much better off than their grandparents. They live in more comfortable, warmer, safer accommodations; eat richer, more varied food; have larger disposable incomes; and enjoy more interesting holidays. We have never had it so good. Look at Henri Cartier-Bresson’s wonderful photographs, Europeans, and you will be reminded just how poor many Europeans still were in the 1950s. If you represent the countries of the world on a map according to the size of their gross domestic product, and shade them according to GDP per head, you can see that Europe is one of the richest blocs in the world.

Shortcomings: Bond Street and the Kurfürstendamm are not typical of Europe. There are still pockets of shaming poverty, even in Europe’s richest countries, and there are some very poor countries in Europe’s east. It is also very hard to establish how much of this prosperity is due to the existence of the EU. In his book Europe Reborn, the economic historian Harold James reproduces a graph that shows how GDP per capita in France, Germany, and Britain grew throughout the twentieth century, with large dips in the two world wars from which we recovered with rapid postwar growth. Overall, prosperity grew at roughly the same rate in the first half of the century, when we didn’t have the European Economic Community, as in the second half, when we did. The main reason for this steady growth, James suggests, is the development and application of technology.

The EU’s single market and competition policy have almost certainly enhanced our prosperity; the Common Agricultural Policy and extra costs generated by EU regulations and social policy almost certainly have not. Countries like Switzerland and Norway have done well outside the EU. In any case, the glory days of European growth are far behind us. In the past decade, the more advanced European economies have grown more slowly than the United States and far more slowly than the emerging giants of Asia.

Diversity

In an essay titled “Among the Euroweenies,” the American humorist P. J. O’Rourke once complained about Europe’s proliferation of “dopey little countries.”

“Even the languages are itty-bitty,” he groaned. “Sometimes you need two or three just to get you through till lunch.” But that’s just what I love about Europe. You can enjoy one culture, cityscape, media, and cuisine in the morning and then, with a short hop by plane or train, enjoy another that same evening. And yet another the next day. And when I say “you,” I don’t just mean a tiny elite. Students traveling with EasyJet and Polish plumbers on overnight coaches can appreciate it too.

Europe is an intricate, multicolored patchwork. Every national (and subnational) culture has its own specialities and beauties. Each itty-bitty language reveals a subtly different way of life and thought, ripened over centuries. The British say, “What on earth does that mean?”; the Germans, “What in heaven should that mean?” (Was im Himmel soll das bedeuten?): philosophical empiricism and idealism captured in one everyday phrase. Awantura in Polish means a big, loud, yet secretly rather enjoyable quarrel. Bella figura in Italian is an untranslatable notion of how a man or woman should wish to be in the company of other men and women.

This is not just diversity; it is peaceful, managed, and nurtured diversity. America has riches and Africa has variety, but only Europe combines such riches and such variety in so compact a space.

Shortcomings: This is the strand on which I see the least credible criticism. Euroskeptics decry the EU as a homogenizing force, driving out old-fashioned national specialities like handmade Italian cheese (with delicious added hand grime) or British beef and beer measured in imperial pounds and pints. But the examples are not numerous, and for every element of old-fashioned diversity closed down by EU regulation two new ones are opened up, from the Caffè Nero on a British high street to the cheap weekend trip to Prague. Europeanization is generally a less homogenizing version of globalization than is Americanization.

Solidarity

Isn’t this the most characteristic value of today’s Europe? We believe that economic growth should be seasoned with social justice, free enterprise balanced by social security—and we have European laws and national welfare states to make it so. Europe’s social democrats and Christian democrats agree that a market economy should not mean a market society. There must be no American-style, social-Darwinian capitalist jungle here, with the poor and weak left to die in the gutter.

We also believe in solidarity between richer and poorer countries and regions inside the EU, hence the EU funds from which countries like Ireland and Portugal have benefited so visibly during the past two decades. And we believe in solidarity between the world’s rich north and its poor south—hence our generous national and EU aid budgets and our commitment to slow down global warming, which will disproportionately hurt some of the world’s poorest.

Shortcomings: This is the strand where Europe’s reality falls painfully short of its aspiration. A significant degree of social solidarity, mediated by the state, prevails in the richer European countries, but even in our most prosperous cities we still have beggars and homeless people sleeping rough. In the poorer countries of eastern Europe, the welfare state exists mainly on paper. To be poor, old, and sick in Europe’s wild east is no more pleasant than it is to be poor, old, and sick in America’s wild west. Yes, there were big financial transfers to countries such as Portugal, Ireland, and Greece, but those to the new member states of the EU today are much meaner. In 2004–06, the “old” 15 member states contributed an average of 26 euros per citizen per year into the EU budget for enlargement—so our trans-European solidarity amounted to the price of a cup of coffee each month.

As for solidarity with the rest of the world, the EU is at the top of Oxfam’s “double standards index,” which measures protectionist practices in the rich north. Our agricultural protectionism is as bad as anyone’s, and the EU is responsible, with the United States, for the shameful stalling of the Doha round of world trade talks.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

These are, I repeat, merely notes toward a new European story. Perhaps we need to add or subtract a theme or two. The flesh then has to be put on the bare bones. Popular attachment, let alone enthusiasm, will not be generated by a list of six abstract nouns. Everything depends on the personalities, events, and anecdotes that give life and color to narrative. These will vary from place to place. The stories of European freedom, peace, or diversity can and should be told differently in Warsaw and Madrid, on the left and on the right. There need be no single one-size-fits-all version of our story—no narrative equivalent of the euro-zone interest rate. Indeed, to impose uniformity in the praise of diversity would be a contradiction.

Nonetheless, given the same bone structure, the fleshed-out stories told in Finnish, Italian, Swedish, or French will have a strong family likeness, just as European cities do. Woven together, the six strands will add up to an account of where we have come from and a vision of where we want to go. Different strands will appeal more strongly to different people. For me, the most inspiring stories are those of freedom and diversity. I acknowledge the others with my head, but those are the two that quicken my heart. They are the reason I can say, without hyperbole, that I love Europe. Not in the same sense that I love my family, of course; nothing compares with that. Not even in the sense that I love England, although on a rainy day it runs it close. But there is a meaningful sense in which I can say that I love Europe—in other words, that I am a European patriot.

Our new European story will never generate the kind of fiery allegiances that were characteristic of the pre-1914 nation-state. Today’s Europe is not like that—fortunately. Our enterprise does not need or even want that kind of emotional fire. Europeanness remains a secondary, cooler identity. Europeans today are not called upon to die for Europe. Most of us are not even called upon to live for Europe. All that is required is that we should let Europe live.