- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Campaigns & Elections

- State & Local

- California

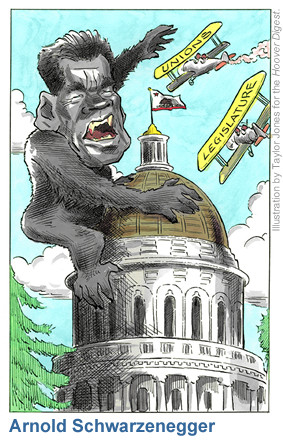

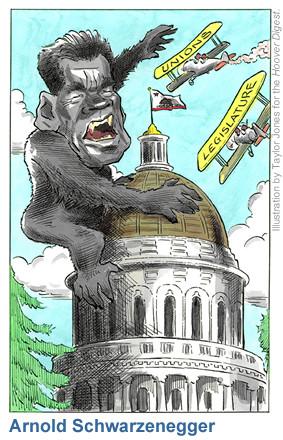

For fans and followers of Arnold Schwarzenegger, the Election Day meltdown this past November elicited the same reaction as the Titanic’s sinking: “It was sad when the great ship went down.” How did this once-unstoppable governor who came into power on the strength of his promise to fix a dysfunctional state capitol end up the big loser in an election called to overhaul government? How could a man whose life has been, for the most part, wall-to-wall success suddenly find himself both humbled and humiliated for the first time in his political career?

There are no simple answers to those questions, only long-winded discourses on greed, ego, and flawed strategy. It’s the stuff of which political science classes and barroom debates are made.

Should Schwarzenegger have terminated the partisan agenda earlier in 2005 and adopted a less confrontational approach to California’s problems? If he was correct in deciding, as his strategists have been spinning, that the choice was fight or give in to the status quo, why did he leave himself so vulnerable to an all-out assault from the public employee unions that left the governor outspent, outflanked, and outmaneuvered come Election Day?

Let’s leave all that to the talking heads and chattering classes. Instead, what deserves closer scrutiny is the paradox that is California’s 38th governor—a leader whose image is embedded in our pop culture but whose policy advancements haven’t taken root.

The Curse of Hiram

No California governor has enjoyed Schwarzenegger’s level of name recognition—95 percent, his pollsters will tell you—at least not while confined in the media backwaters of Sacramento. But maybe 5 percent of Californians can list three things that his administration has been up to these past two years (e.g., workers’ compensation reform, reducing the state’s structural deficit), much less cite three policy priorities that weren’t on the special-election ballot in November.

How could this be? It’s not as if Schwarzenegger lacks for attention and can’t draw a crowd of reporters at the drop of a hat. But one explanation might be that the former Mr. Universe at times is too in love with issues of a universal scope—the hydrogen highway, 1 million solar-paneled roofs for California homes, or curbing global warming in the Golden State.

It’s not unlike an oncologist who goes into practice not to treat patients but rather to cure cancer. During his first two years on the job, Schwarzenegger has showed little interest in the smaller steps sometimes required to accomplish major reform over time; nor has he seemed willing to pay much attention to the less-sexy side of governing the nation-state—like signing proclamations that don’t accomplish big-picture goals but let people know you care about their day-to-day concerns.

Even when the governor did sweat the small stuff—like when he reversed himself last fall to support cracking down on students’ use of steroid-like supplements, or when he suddenly embraced the removal of soda machines from California’s public high schools—his office did little more than issue a press release. No press conferences and no showmanship equaled almost no coverage amid negative special-election news. It also denied him the chance to show that, in addition to being physically strong, he can also be politically flexible.

What the governor and his handlers forgot is that it’s the more mundane maintenance aspect of the job—touching base with Californians on the environment, health care, education, infrastructure, the jobs climate, and public safety—that gives an executive his identity and support among regular people. Such backing could have come in handy in the months leading up to the special election; Schwarzenegger and his ambitious agenda were easy pickings as too much politicking, too little governing.

If there was a lesson for Team Arnold to learn in the special-election setback, it’s that California’s public employee unions were far too effective in painting Schwarzenegger, the erstwhile “people’s governor,” as an enemy of the people—firefighters, police, nurses, and educators in particular.

Think of Schwarzenegger’s problem as the “curse of Hiram.” California’s governors invariably enter office with one of two role models in mind—Pat Brown, the great builder of roads and schools, or Hiram Johnson, the great political reformer who fought corporate influence and gave California the initiative process. And although Schwarzenegger is fond of Reaganesque comparisons and even keeps a bust of California’s 33rd governor in his office, it’s Johnson’s name and legacy he chose to invoke on the campaign trail. Here’s the rub: Being California’s second coming of reform is a noble idea, but it shouldn’t come at the cost of the grunt work of being a governor.

This is not to suggest that the past two years of Arnold-mania translate to a blank page. He did talk the Democrats into enacting workers’ compensation reform. Without his looming presence in Sacramento, the car tax would not have been lowered and lawmakers would still be ripping off gasoline tax revenues for things having nothing to do with transportation. Thanks to a stroke of his pen, you can drive your hybrid in the diamond lanes on state freeways. And same-sex couples can live their lives with greater dignity, thanks to this governor’s embrace of a law that requires health insurance companies to treat all couples the same.

But those actions are drops in the bucket compared to the exhaustive agenda Schwarzenegger unveiled during his recall campaign—and that has since gone missing. Two years later, where’s the progress on education reform, more affordable health care, and streamlining government? What business agenda other than overseas trade and investment is currently being promoted by the governor who, the unions cried throughout the long special-election campaign, was a tool of corporate California?

It’s an incomplete scorecard, to be polite. And, by the fall of 2006, you’re sure to hear his Democratic opponent giving Schwarzenegger an F for unfulfilled promises.

Small Ball

So what’s a Governator to do? The good news for Schwarzenegger is that he has the ability to recapture what once was a sterling reputation; he is a rare celebrity who noncondescendingly connects with working folks. And there’s an easy way to go about it. It requires, however, doing something that may be hard for Republicans to swallow: taking a page from Bill Clinton’s book and engaging in “small ball” for the first eight months of 2006, until Labor Day and the historic kickoff of the November election.

What exactly is “small ball”? You might know it as “triangulation”—borrowing some of the other party’s ideas to absorb the political center. Clinton did this by endorsing concepts like school uniforms. No question such moves are “small” in that the ideas aren’t gigantic—certainly not the stuff of which action heroes are made. But, done consistently and over time, they allow a politician to connect with the electorate.

The big question now is whether Schwarzenegger will see the value of small ball or will, instead, act like a driver who hits an icy patch and turns the wheel hard in the opposite direction. In other words, will he see himself as deeply wounded and even deeper in trouble and steer so far left that his Republican supporters don’t recognize him? Does he raise taxes and support a more generous state minimum wage? Does our he-man governor put himself at the mercy of Speaker of the Assembly Fabian Nuñez, who’s a bantamweight in size but whose aggressive campaigning KO’d the governor in the special election?

It would be an understatement to say that this scares rank-and-file Republicans. They see the governor as in a skid but certain to regain traction. A complete change in direction (and loss of control, they argue) would inevitably lead to a big crash.

This may be the biggest test of Schwarzenegger’s political life. Does he have the patience and inner fortitude to ride out the current bad stretch, or does he overreact and, at least from a Republican point of view, make a bad situation worse? Is Schwarzenegger interested in merely the symbolism of bipartisanship (à la Clinton, who supported school uniforms but not school vouchers), or does he venture all the way across the aisle and start endorsing ideas previous Republican governors would have shunned?

I would argue that he doesn’t have to go that far to regain his reputation as a bipartisan problem solver. It’s easy to see Schwarzenegger and legislative Democrats reaching common ground on a multibillion-dollar infrastructure bond, redistricting reform, and even a prescription-drug benefit that could have and should have been inked last year. Democrats and Republicans aren’t too far apart on any of those issues.

But because the governor is still a newcomer, relatively speaking, to politics, it’s anyone’s guess how strongly he will react to this loss.

Let’s face it, up until now, Schwarzenegger has had it pretty easy. He first entered the political arena in the late 1980s as “Conan the Republican”—a fund-raising draw and chairman of the President’s Council on Physical Fitness, with endless one-liners about his famous in-laws. Pretty tame stuff. Even the recall election was relatively safe ground; he was, after all, challenging a notoriously unpopular governor. But the special election was a large serving of humble pie, not something usually on the governor’s diet plan.

Pumping Up the Vote

As we search for clues to what Governor Arnold, version 2.0, will resemble by Election Day this coming November, his recent State of the State address should be a good indicator. In its first two years, the Schwarzenegger administration has front-loaded new policy into that yearly address, cramming all its big ideas into one huge speech. That meant that some good ideas just got overwhelmed, and all it takes is one bad idea to make the big speech otherwise forgettable. That’s what happened in 2005, when a flawed pension-reform proposal sank what was otherwise a good address.

That was not the case in this year’s State of the State address. Schwarzenegger spoke for only 25 minutes—less than half the time of a presidential State of the Union address. And he offered just three basic themes: He was sorry for last year’s politicking; he wants to rebuild California by taking out some $70 billion in infrastructure bonds; and his door is open to any lawmaker with a good idea.

But what ideas? Anything that will score political points, it seems. Schwarzenegger not only wants to rebuild schools and highways, he also wants to raise the state’s minimum wage, import prescription drugs from Canada, spend more on K–12 education, and freeze tuition at public universities. The merits of that agenda are dubious, yet there’s no debating its potential effectiveness in cleaning up the image of a politician who was painted as an enemy of teachers and the working class.

Still, it leaves a nagging question: Does Schwarzenegger represent a movement, or, like so many other politicians, does he merely live in the moment? He ran in the October 2003 recall election as an outsider committed to reforming Sacramento’s practices. So far, his agenda for 2006 is that of an insider, looking for compromise from within the system. Time will tell if the “new” Arnold can revert to the original Governator who so charmed California voters.

But the most important question may be whether he is willing to do the grunt work to show voters that he does indeed possess a vision—that there is actual substance behind his mantra of “action, action, action.” In bodybuilding terms, it’s the equivalent of taking weight off the bar but doing more reps.

It may not be the big-weight, big-lift this governor loves. But it may be the most sensible way for Arnold Schwarzenegger to once again pump up the vote.