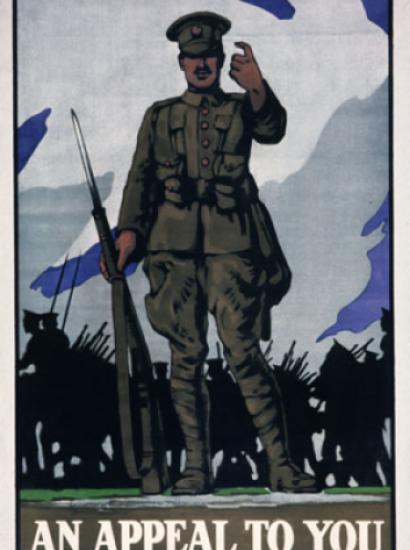

Europe used to be a continent of warriors, but no longer is. For about 2000 years, Europeans excelled at massacring one another, and then with mounting efficiency and furor as the two world wars have demonstrated. They were also a race of conquerors, sailing forth from the 15th century onward to occupy the four corners of the earth. In the process, they invented the arsenal of modern war from the crossbow to the U-Boat, from mass to gas warfare. No more.

Where Have Europe's Warriors Gone?

Above all, the warrior culture is gone, and with it, the values that celebrated duty, honor, manliness, self-sacrifice, and what Tocqueville called the “poetical excitement of arms.” For all its über-modernity, the United States still has such a culture, rooted mainly in the South, including Texas. Among the Europeans, the British and the French, ex-imperial powers both, retained at least remnants of this culture, but it is dwindling as well. A recent data point is the resounding defeat David Cameron suffered in the House of Commons when he called for a war resolution against the Assad regime. Not to be outdone by their archrival, more than two-thirds of the French said “non” to participation. If President Hollande went to the National Assembly, he, too, might go down.

More significant is the creeping demise of Europe’s armies. The UK’s regular forces are to shrink to their lowest size in 150 years. The French government wants to cut 30,000 over the next six years. The Germans, fielding more than 600,000 when divided into East and West, are down to 185,000–and falling.

By themselves, these numbers don’t mean much, not in an age when mass warfare seems passé. But smaller will not be more beautiful, given dwindling defense budgets. Even two years ago, NATO Secretary bemoaned the fact that the European members had cut their spending by $45 billion, which is the size of the German budget. And with the end of the Afghanistan venture, more cuts are coming. The French, once trailing only the British among the big E.U. countries, want to reduce to1.3 percent of GDP. By comparison, the U.S., never mind the sequester, is spending 4.4 percent.

Such trends do not foreshadow meaner and leaner armies, for these are highly capital-intensive. The Europeans are cutting faster than they are buying into useable, that is, mobile forces, such as transport and tanker aircraft, supply and fighting ships, longer-range bombers and tactical helicopters, stand-off weapons and battlefield surveillance. Not to put too fine a point on it, Europe’s armies are being compressed into mini-Cold War formations, minus the thousands of heavy tanks once deployed to lunge across the North-German Plain.

To put it more harshly: European nations cannot fight a war beyond their borders, neither singly nor in combination, given their competitive rather than complementary procurement. When they last did fight in Libya, they ran out of ammunition in short order, having to hit up the U.S. for ordnance and battlefield surveillance. So much for a continent whose potentates (Napoleon, Hitler) once went all the way to Moscow and Cairo, not to speak of North America in the 18th and Africa in the 19th centuries.

Historians scratch their heads. The population of the EU-27 exceeds America’s by almost 200 million. Its GDP comfortably outstrips the American one. Europe’s riches are the puzzle, not the answer. The explanations come in a grab bag. The two world wars have extinguished the fires of nationalism and hence the will to grandeur. From some 60 million dead, the Europeans have drawn the conclusion that, short of self-defense, there is little worth fighting for. Life under America’s strategic umbrella has taught the Europeans how dulce et decorum it is to outsource even self-defense.1

Their lost colonial wars have taught them that force doesn’t buy anything, except blood, sweat and domestic revulsion. Those who fought in Iraq and Afghanistan had the lesson refreshed a few decades later. Last, but certainly not least: the warfare-welfare squeeze. Since the War, Europe has rewritten its “social contract” in favor of welfare and redistribution. Give or take a few points from country to country, 30 percent of GDP are now devoted to a rich array of transfers. The United States hasn’t exactly been idle on this front, but with a decisive difference. The U.S. spends three times more as a fraction of GDP on defense than its European brethren.

Will Europe recoup its capabilities? The trends and the data say “no.” And why should Europe do so? There is no strategic threat on the horizon as far as the eye (and satellites) can see. In spite of all the hoopla about “pivoting” and “rebalancing,” the Europeans know that the U.S. cavalry will ride to the rescue if the threat re-materializes. In locales farther beyond, both Europe and the U.S. are losing their appetite for intervention because wars of order have proven costly and futile. It may well be “Sweden” for the rest of Europe. A mighty player and the scourge of the Continent in the 17th century, Sweden is now as aggressive as a reindeer, foreshadowing Germany’s metamorphosis into a Greta Garbo power (“I want to be alone.”). Russia, Iran and China are watching attentively.

1 Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori is a famous line from the Odes (3.2) of Horace. Roughly translated: “It is sweet and right to die for your country.”