- Economics

- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- Energy & Environment

- US

- Contemporary

- Economic

- World

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- History

Where will Russia go this year? Under Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev, Russia is not a democracy, but neither is the government heading back to Soviet-type totalitarianism. The absence of political competition is not Russia’s primary problem; it is the absence of the rule of law.

Russia today has markets and private property. It is not the Soviet totalitarian state; nor is it, strictly, a “mafia state.” That is one step forward. But Russia’s government seeks the power to intervene at will, selectively and at its own discretion, in markets and property relations. The government stands above the law. The result is two steps back. You can see this clearly in the four stories that follow.

Story number one: Russia suffered a harvest failure and nobody died. Last summer saw a severe drought across Russia. Harvests failed disastrously. In the Soviet past, failures on similar proportions occurred in 1932 and in 1946. When those harvests failed, there were severe regional famines in which millions of people starved to death.

After the harvest failure of 2010, two things happened that were in striking contrast with the Soviet past. First, no one died. Instead, when food prices at home threatened to rise, the Russian government responded by imposing an export ban, requiring Russian food suppliers to break their contracts with foreign buyers. Second, this exposed the fact that for the first time since the 1920s, Russia is exporting food to the West. Under a market economy, Russian agriculture has become a competitive success. (It does not take much to be a success by Russian standards.)

The reflexive response of the Russian administration—to try to control prices by restricting the market and breaking contracts—was a bad sign, however. This will limit the incentives for Russian farmers to make the forward-looking investments that will reduce harvest volatility in the future. Foreigners will become less ready to make forward contracts for Russian exports, knowing the state can override them at any time.

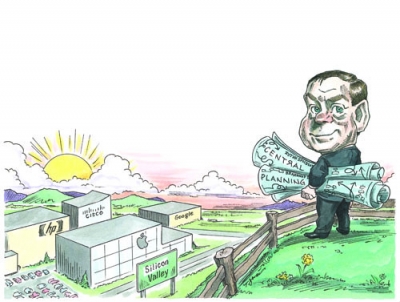

Story number two: President Medvedev has seen the future, but can he make it work? In 2010, Medvedev visited Silicon Valley, the world’s biggest concentration of innovative start-up ventures. Now, the Russian government wants to build an analogue in the district of Skolkovo, outside Moscow.

The goal is to promote five presidential high-tech directions (one is tempted to substitute the Soviet-era jargon of “priorities”) of modernization: energy production, information technology, telecommunications, and biomedical and nuclear technologies.

There is some sound logic behind this. Economic development does require new urbanized configurations. And it’s true that Russians today don’t live in the right places for innovation.

Most Russians are spread out across the country’s vast landmass in small and medium-sized towns. They are too immobile (apart from the ones who have gone to live abroad, many in places like Silicon Valley). Lots of young people need to move to big sprawling cities and suburbs to squash up and rub together, mix ideas and talents, get funding, and start up innovative ventures. In fact, quite a lot of them would like to but can’t, because Moscow is congested and operates a restrictive system of residence permits.

Like other poor countries, Russia may also need to experiment in new ventures to uncover comparative advantages.

In short, there is a respectable case for the Russian government to do more to encourage movement away from rural districts and remote small towns, and let its largest cities grow further. It should also stand ready to subsidize pioneering entrepreneurs.

But what Medvedev actually has in mind is to create a controlled environment for approved people and favored companies to sit in a green field outside Moscow. This is not how Silicon Valley was born. The Russian government will not be able to commit itself not to meddle and grab. The powerful military-industrial lobby will not be able to stand aside and let individual enterprise make and take profits.

If it is ever built, Russia’s innovation city will drain the state budget of grants and subsidies. There will be just enough spinoffs that everyone will declare it a success. The aggregate net benefit will be zero or negative.

Story number three: Russia writes a new law on the secret police. After the Soviet Union collapsed, Russia went from a government system of micro-controls on everything to too little government control. In the 1990s, public confiscation was replaced by “piratization” (from the title of a book by Marshall Goldman). The Russian state went from having far too much capacity to having too little capacity to raise taxes and regulate public life. In fact, the thing that gave the first Putin administration its legitimacy was public recognition that some restoration of state capacity was deeply necessary.

Up to a point.

But Prime Minister Putin is a KGB alumnus, and part of his mission has been to restore the power and prestige of Russia’s secret services.

Russia’s parliament has given first reading to a new law on the FSB (the domestic security service) that illustrates the direction of movement today. It gives the FSB the power to issue legally binding warnings to people who might be about to undertake illegal actions. This reinstates the legal basis of the KGB practice of controlling the behavior of people who were on the edge of political or cultural deviance or defiance by warning them off.

The reinstatement of the early warning system matters not only in itself, but also for what must lie beneath. The KGB’s ability to control deviance by giving out early warnings rested on a vast apparatus of informers and mass surveillance. It could hand out tens of thousands of warnings a year across the vast Soviet territory because it kept individual tabs on millions. Mass surveillance enabled the selective intervention that kept the population quiet and conformist.

The new law on the secret police does not bring back totalitarian control, but it makes little sense unless the FSB is quietly rebuilding its networks of spies and informers on a mass scale.

Story number four: some go to jail, some go free. After violent demonstrations in London over university tuition increases, the British police identified and arrested 180 participants suspected of significant responsibility. After race riots in Moscow, the Russian police rounded up no fewer than 800 ringleaders (I don’t know what happened to them after that). So there is something, at least, that the Russians can do better!

No one I know is likely to shed any tears over the fate of violent ultranationalists and fascists. I confess to feeling ever so slightly sorry for them. The Russian government used them as a lightning rod until the voltage ran out of control; now they can be slapped down, at least for the sake of appearances. Moreover, the same police who could locate and arrest hundreds of suspects in the course of a weekend seem unable to find the murderers of dozens of journalists killed in Russia during the Putin era. Hmm.

Which brings me to the latest victim of selective Russian justice: Mikhail Khodorkovsky. Khodorkovsky was put away originally for trying to break away from the “mafia state” that gave him his fantastic wealth. The first time, he was put away for evading taxes on his company’s profits. The second time, it was for stealing his company’s entire revenues.

If you treat this literally, it is then hard to explain how it was that his company was making taxable profits at the same time that Khodorkovsky was stealing the revenues. But the underlying principle is not that complicated. In Russia, the state decides first who is guilty. Then it decides what he is guilty of.

It is cheering to see violent thugs get what’s coming to them, but it is still a mistake to cheer at the sight of a few unpleasant people put behind bars. Under the rule of law, you go to prison because you have broken the law, not because some official has decided you might be a threat.

These four stories suggest where Russia is moving: toward a state with increased discretionary power to intervene as it chooses to control prices and direct resources, subsidize favored interests, monitor deviance, and lock up or kill inconvenient people. By the standards of Russia’s Soviet past, they definitely represent one step forward. This one step is hugely important. Russia is no longer a totalitarian state of mass mobilization and thought police. But compared with the “normal” society that Russians deserve, and Russia’s friends wish for, it is two steps back again.