While Washington was trying to arrange a bailout of the domestic auto industry, the Detroit Three and their union, the United Auto Workers, kept insisting that bankruptcy would be the kiss of death. Not so: a Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing would probably result in a stronger domestic industry.

Why? Consider that the fundamental question to ask of any firm facing bankruptcy is whether it failed economically or simply failed financially.

If a typewriter manufacturer were to file for bankruptcy today, it would probably be considered an economically failed enterprise. The market for typewriters is small and shrinking, and the manufacturer’s financial, physical, and human capital would probably be better redeployed elsewhere, such as in making computers.

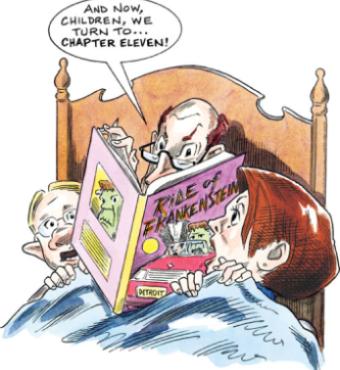

A financially failed enterprise, on the other hand, is worth more alive than dead. Chapter 11 exists to allow it to continue in business while it reorganizes. Reorganization arose in the late nineteenth century, when creditors of railroads unable to meet their debt obligations threatened to tear up their tracks, melt them down, and sell the steel as scrap. But innovative judges, lawyers, and businessmen recognized that creditors would collect more if they all agreed to reduce their claims and keep the railroads running and producing revenues to pay them off. The same logic animates Chapter 11 today.

General Motors looks like a financially failed rather than an economically failed enterprise—in need of reorganization, not liquidation. It needs to shed labor and retirement contracts and modernize its distribution systems by closing many dealerships. This would give rise to many current and future liabilities that might be worked out in bankruptcy. It may need new management as well. Bankruptcy provides an opportunity to make those changes. Consumers have little to fear: reorganization would pare the weakest dealers and strengthen those who remain.

So why do the Detroit Three managers and the UAW insist that “bankruptcy is not an option”? Perhaps because of the pain that would be inflicted on both.

The bankruptcy code places severe limitations on the compensation that can be paid to a manager unless there is a “bona fide job offer from another business at the same or greater rate of compensation.” Given the dismal performance of the Detroit Three in recent years, it seems unlikely that their senior management would be highly coveted on the open market. Incumbent management is also likely to find its prospects for continued employment less secure.

Chapter 11 also would provide a mechanism for forcing UAW workers to take further pay cuts, reduce their gold-plated health and retirement benefits, and overcome their cumbersome union work rules. The process for adjusting a collective bargaining agreement is somewhat complicated, beginning with a compulsory mediation process. But if this fails a company can (with court permission) nullify the agreement. This doomsday scenario is rarely triggered, however, as its threat casts a large shadow over negotiations, providing a stick to force concessions.

Those Washington politicians who repeat the mantra that “bankruptcy is not an option” probably do so because they want to use taxpayer money to bribe Detroit into manufacturing the hybrid cars favored by Nancy Pelosi and Harry Reid, rather than the cars American consumers want to buy. A Chapter 11 filing would remove these politicians’ leverage, which explains their desperation to avoid bankruptcy proceedings.

In short, Detroit and the public have little to fear from a bankruptcy filing but much to fear from a corrupt bargain among incumbent management, the UAW, and Capitol Hill to spend our money to avoid their reality check.