- International Affairs

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

After 15 years of tumultuous change in Russia, Moscow is booming and parts of the city give the impression that they are part of the West.

Tverskaya Street, the capital’s principal artery, is filled with strollers, late-model cars, and outdoor cafés. On Novoslobodskaya Street, coffeehouses are filled to capacity and consumers crowd the new “Friendship” Russo-Chinese shopping center. Everywhere, restored buildings reveal the beauty of Moscow’s nineteenth-century architecture; at night the illuminated facades of the buildings and gleaming cupolas of the churches create an atmosphere of dynamism and resurgent grandeur.

But the state of Russia is not simply a matter of surface appearances. The reforms that remade Russia took place without the benefit of higher values, and they bequeathed to Russia a moral vacuum. The result is that behind the facade of relative prosperity made possible by Russia’s improving economy, Russia faces underlying problems—criminalization and lawlessness, disregard for human life, and a deep spiritual malaise—that define the circumstances of the country’s existence and threaten its long-term survival.

A Roof of Corruption

The lawlessness in Russia defines the tenor of everyday life. Business in Russia operates according to the law of the jungle: the most basic functions can only be carried out under the protection of armed force.

On the street, gangsters create a sense of permanent insecurity for millions of citizens. It is impossible in Russia simply to run a business; that business must have protection, which Russians refer to as a “roof” (krysha). This roof is provided by a criminal gang that protects businesspeople from other criminal gangs (as well as itself) in return for a share of their income. The system of roofs is so well established that entire regions are divided up between rival gangs, and businesspeople turn to the gangs to settle their disputes and collect their debts. Moral boundaries have become so blurred that many Russians treat the demand that they hand over a share of their income as a legitimate obligation.

The gangs’ only real competitors are law enforcement agencies. For a long time, the gangs had a near monopoly on extortion, but, as the heads of law enforcement agencies saw the enormous profits that were possible, they too entered the protection racket. Today, security firms connected to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Regional Directorate for Combating Organized Crime (RUBOP), and the Federal Security Service also offer protection to paying clients, particularly in Moscow. The official roofs have some advantages over the criminal roofs, in that they are less likely to betray their clients and, unlike the gangs, can be fired. But the involvement of police agencies in the protection racket undermines the whole notion of law enforcement and implicitly treats extortion as a normal part of life.

Government for Sale

Whereas the protection racket dominates Russian business at the street level, the government serves as the roof for oligarchic businesses that have their own security and are thus not vulnerable to crude racketeering.

When the reforms in Russia began, money was in the hands of gangsters and black market operators and property was in the hands of government officials. The first priority of virtually every new enterprise was therefore to buy government officials. Soon Russia came to be dominated by oligarchic clans that had, in effect, put the government on their payroll. The result is a country characterized by both massive poverty and a striking concentration of wealth. Eight oligarchic groups today control 85 percent of the value of Russia’s top 64 private companies, and the combined sales of the 12 top private companies equal the revenue of the government.

An example of how the system operates was provided by MDM, one of the most powerful banking groups in the country. In the years since Vladimir Putin acceded to power, MDM acquired Russian industrial giants, including defense plants, at a speed that would not have been possible without the government’s protection. MDM became interested in Nevinnomissky Azot, one of Russia’s largest fertilizer factories, but met resistance from the factory’s director, Viktor Ledovsky, who set up a firm through which workers could buy shares in the factory. He appealed to the government not to sell its stake in an enterprise that was making a profit. In response, the tax police arrested Ledovsky on charges of hatching a scheme to steal money from the workers, despite a statement from the Russian Institute of the State and Law that his activities were legal. With Ledovsky in prison, the government sold its interest in Nevinnomissky Azot for the lowball price of $25 million to a group representing MDM.

Many of the principal oligarchic clans—united by their connections to Boris Yeltsin and his immediate relatives—are known collectively as the “family.” With the accession of Putin, however, the family has faced competition from the “Leningraders,” mostly associates of Putin and veterans of the intelligence services. The basic situation, however, has not changed.

One of Putin’s favorite oligarchs is Oleg Deripaska, the director of Russian Aluminum, which produces nearly 80 percent of that metal in Russia. Dzhalol Khaidarov, a former close associate of Mikhail Chernoy, a partner of Deripaska’s with close ties to organized crime, described, in an interview with Le Monde, how Russian Aluminum became so large: “You ask why Russian Aluminum gained one or another factory. They will say that the shares were purchased. But if you look, you’ll find that the former shareholder is in prison, became a ‘drug addict,’ or disappeared. When I worked with Mikhail Chernoy, the group gave bribes of 35 to 40 million dollars every year. It was always possible to buy a judge, a governor, or a law. In the early 1990s, they murdered. Now they prefer to file a case or put someone in prison. They can do anything.”

The Cheapness of Human Life

The current murder rate in Russia (40,000 a year) is triple the rate in 1990, giving Russia the highest murder rate in the world after South Africa. But even this appalling number may be a serious underestimate. According to Russian demographers, there are another 40,000 violent deaths a year in which the cause of death—murder or accident—cannot be established, and in 20,000 cases a year, individuals simply disappear.

According to the journal Demoscope Weekly, the figures for all categories of violent death in Russia far exceed their Western equivalents. A comparison of Russia and England, for example, shows that a Russian is 3 times more likely to die in an accidental fall than an Englishman, 5 times more likely to die in a traffic accident, 7 times more likely to commit suicide, 25 times more likely to accidentally poison himself (usually with alcohol), 31 times more likely to drown accidentally, and 54 times more likely to be murdered.

Among the reasons for the lethality of Russian life is that when a life-threatening situation occurs, Russians can rarely count on timely help from emergency services personnel.

Besides the hazards of everyday life, the low value assigned to Russians’ lives is reflected in the readiness of the government to sacrifice them. This was reflected in the reform program that was undertaken in the 1990s with little regard for its effect on the health of the population, resulting in 5 million premature deaths—the result of a surge in cardiovascular illness and an epidemic of accidents and violent crime. It is also reflected in the Chechen wars, in which the authorities have shown little regard for the lives of Russian soldiers or Chechen and Russian civilians.

The most graphic illustration of the authorities’ indifference to human losses, however, took place during the hostage crisis in October 2002 at Moscow’s Dubrovka Theater. Chechen terrorists (many of whom had explosives strapped to their body) seized 800 hostages, seeking to negotiate an end to the war in Chechnya. In the initial stages of the crisis, Putin said that saving the lives of the hostages was his first concern, and there were clear indications that a peaceful solution was possible. Yet the Russian authorities never engaged in—or apparently even considered—serious negotiations with the terrorists. In the end, the theater was flooded with toxic gas and stormed by security forces. All 41 of the terrorists were killed, many of them shot while they were unconscious. More than 100 hostages were dead, all but three of whom died from the gas being used to “rescue” them. Doctors arriving at the scene were not told that the hostages had been gassed and thus could not provide the necessary antidote. The order for ambulances to proceed to the theater came 45 minutes after the beginning of the operation. Countless lives were needlessly lost due to the ineptitude of the rescue operation. The refusal to negotiate and the nature of the rescue effort suggest that saving the lives of the hostages was a very low government priority indeed.

A Vast Moral Vacuum

Russia’s future is also threatened by an even more fundamental problem: a deep spiritual malaise that reflects the inability of Russia to find a new moral orientation in the wake of the fall of communism.

The communist regime was based on “class values”—the notion that right and wrong are determined by the interests of the dominant class. In the wake of communism’s fall, moral coherence for society could only be achieved through establishing universal values that, as a practical matter, required the efforts of the Russian Orthodox Church or the government or both.

But the moral authority of the church has been crippled by its widespread corruption and its history of collaboration with the KGB. Church hier-archs and ordinary priests alike have pursued commercial interests, blessing businesses, banks, homes, and automobiles for a fee. At the same time, the church has remained silent on such genuine moral issues as Russia’s pervasive corruption and the killing of noncombatants in Chechnya.

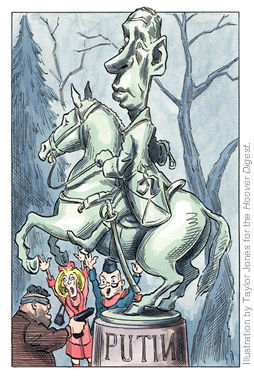

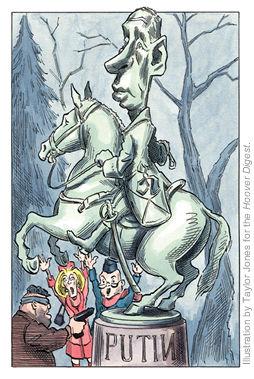

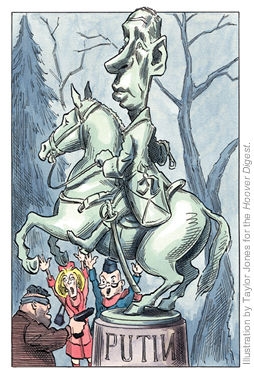

The government has contributed to Russia’s moral malaise by seeking to legitimize authoritarian rule by glorifying state power. One disturbing aspect of this effort is the cult of personality that has been created around President Putin, which includes everything from sculptures and paintings to a mountain named for him in Kyrgyzstan to his own youth movement (“Forward Together”).

Perhaps more important than the Putin personality cult, however, is the development of a new ideology that identifies Russia’s future well-being with the power of the Russian state. Propounded by intellectual and political figures who describe themselves as statists (gosudarstvenniki), this outlook treats Russian history as the story of the development of the Russian government, in which the Soviet period was only one episode. An inevitable result of this approach is to rehabilitate communism and gloss over the lessons of the communist period, making it that much harder for Russian society to gain the democratic, moral orientation that it needs.

A Moral and Legal Framework

Both in Russia and the West, there has been a tendency to interpret success in Russia strictly in economic terms. But Russian society lacks moral foundations, and those in power often interpret liberty as the freedom to do whatever they want, regardless of the welfare of others.

Much of the discussion of the Russian reform experience concerned the relative merits of “shock therapy” versus government regulation, but a market economy—based on equivalent exchange—can only be guaranteed by a framework of morality and law. Without such a framework, the result is just another articulation of the rule of force.

In the final analysis, Russia can only overcome the systemic problems that threaten its future by respecting the dignity of the individual and establishing the authority of transcendent, universal values as reflected in the rule of law.