- US Labor Market

- International Affairs

- Economics

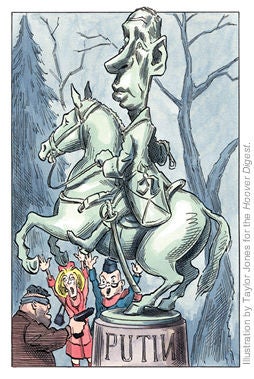

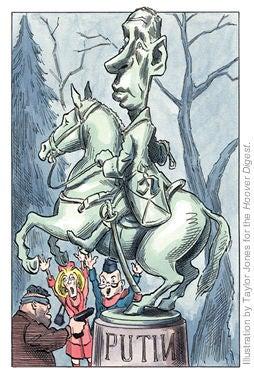

Illustration by Taylor Jones for the Hoover Digest Illustration by Taylor Jones for the Hoover Digest |

“The rule of law concept,” John Whyte has written, “is based on the praise of rules. Rules, rather than being seen as prisons, or impediments to developing rich and supporting social communities, are seen as the condition for freedom and diversity because they limit, with the force of law, those that seek to limit others. The rule of law rests on the moral satisfaction of observing promises, honoring commitments and enforcing legitimate rules.” And he concludes: “These outcomes are morally satisfying because they give purpose to one’s autonomy. . . . The rule of law is hostile to arbitrary force, especially when it takes the form of state action, because that force leaves individuals with no control over their own futures.”

Contrast that Western view of the rule of law with the Russian view, enunciated by President Boris Yeltsin himself: “Everyone knows that we Russians do not like to obey all sorts of rules, laws, instructions and directives. . . . We are a casual sort of people and rules cut us like a knife.”

That Russia under Yeltsin has become an enormously lawless and corrupt state is well known, but I believe the extent of its corruption is difficult for many Westerners, and even specialists in Russian politics, to grasp. Evidence of corruption, cronyism, and Yeltsin’s authoritarian tendencies have been present since the early days of his regime. One chilling incident from 1994 illustrates that, in dealing with Boris Yeltsin’s Russia, we are dealing with a lawless state. Many of the details come from the memoirs of General Alexander Korzhakov, Yeltsin’s former chief bodyguard. Statements by General Korzhakov must be treated with caution, but in this instance he seems reliable.

Given the increased lawlessness in Russia’s capital, it has become common for the new breed of powerful Russian plutocrats to whisk around Moscow with large contingents of bodyguards as if they were themselves heads of state. These moguls control enormous empires and enjoy pushing their weight around. In the winter of 1994, one of these moguls, Vladimir Gusinski, a media and banking magnate, made the mistake of stepping on Boris Yeltsin’s toes.

On December 1, 1994, ten days before the Russian invasion of Chechnya, Boris Yeltsin complained bitterly during a meal with General Korzhakov and his colleague, General Mikhail Barsukov, head of the Kremlin Guards: “Why can’t you take care of this Gusinski person?! What is he up to? Everyone is complaining about him, including my family. How many times has it happened that Tatyana or Naina [Yeltsin’s daughter and wife] is riding in a car and the road is closed off because of that Gusinski? His NTV [television station owned by Gusinski] has cast aside all restraint and is behaving insolently. I order you: Take care of him!”

Evidence of corruption, cronyism, and Yeltsin’s authoritarian tendencies are not a recent phenomenom—they have been present since the early days of his regime.

On the following morning, December 2, armed men dressed in paramilitary gear, wearing no distinguishing badges, arrived at Gusinski’s dacha outside of Moscow. They belonged to a special unit attached to the presidential security service and headed by Korzhakov’s assistant, Rear Admiral Gennadi Zakharov, who had earlier served abroad as a Soviet saboteur.

The seven cars carrying Zakharov’s heavily armed unit followed Gusinski and his personal bodyguards as they drove from the dacha to a building in central Moscow housing Gusinski’s Most Bank and also offices of the mayor of Moscow, Yuri Luzhkov. As they drove into Moscow, Zakharov’s men attempted to provoke Gusinski’s guards into an exchange of fire, but the latter “did not give in to the provocation.” If they had, then Gusinski might have been killed in the crossfire.

Sometime after Gusinski had arrived at the Most building, Zakharov’s heavily armed men, wearing ski masks, seized several of Gusinski’s body-guards and drivers and forced them to lie down on the snow-covered ground for a period of two hours. Watching this scene from his office, an alarmed Gusinski telephoned Yevgeny Savostyanov, deputy chairman of the FSK (secret police) and director of that organization’s operations in Moscow, who sent some men to check out the situation. These operatives reported back that the presidential security service was behind the incident. This identification immediately cost Savostyanov his job. The FSK group had arrived at the Most building at 2:00 p.m., and by 4:00 p.m. Yeltsin had signed papers releasing Savostyanov from his duties. Shortly thereafter Gusinski, after being severely harassed at the airport, was able to flee abroad until such time as his political prospects improved.

This incident typifies and encapsulates Boris Yeltsin’s concept of the rule of law. For Yeltsin, such issues as freedom of the press, freedom of speech, and freedom of movement pale before the desire to deal brutally with political opponents and enemies. Until Russia has a leader who embraces the rule of law—and there appears little prospect of that happening over, say, the next five years—that unhappy country is likely to continue its descent into chaos.