- Education

- K-12

- State & Local

- Budget & Spending

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Economics

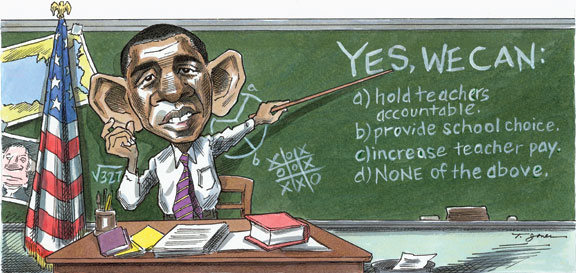

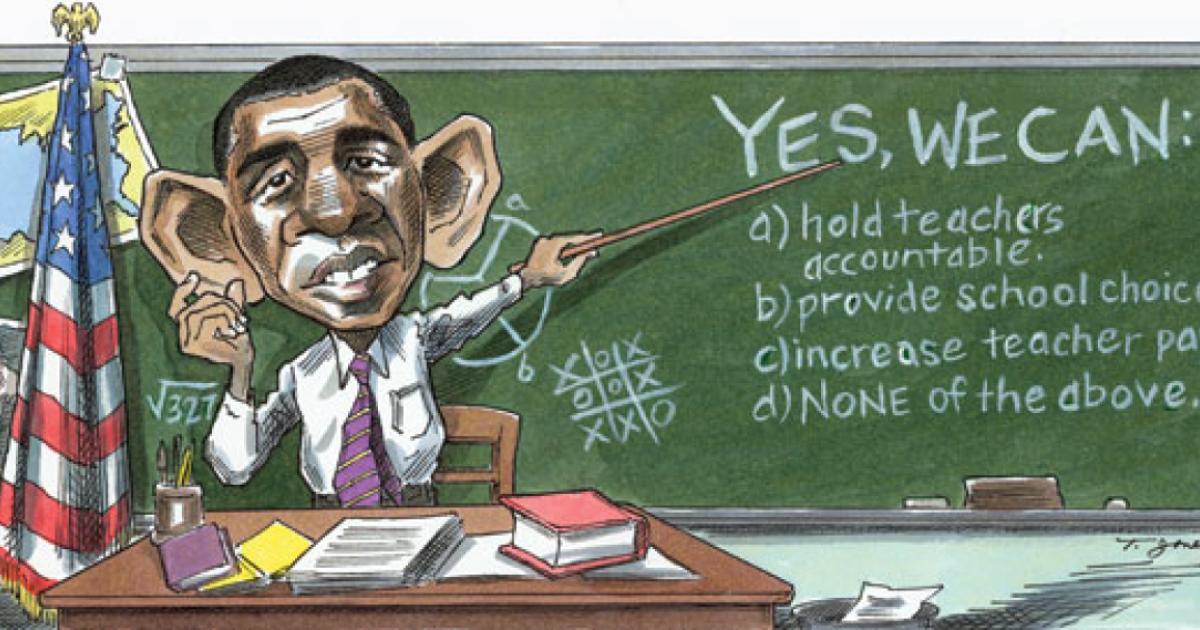

Can President Obama bring change to American education? The answer is yes, he can. The question, however, is whether he actually will. Our new president has the potential to be an extraordinary leader, which is why I suppported him in the 2008 election. But on public education, he and his fellow Democrats are faced with a dilemma that has boxed in the party for decades.

Democrats are fervent supporters of public education, and the party genuinely wants to help disadvantaged kids stuck in bad schools. But it resists bold action. It is immobilized, impotent. The explanation lies in its longstanding alliance with the teachers’ unions, which, with more than 3 million members, tons of money, and legions of activists, are among the most powerful groups in American politics. The Democrats benefit enormously from all this firepower, and they know what they need to do to keep it. They need to stay inside the box.

And they are doing so. Democrats favor educational “change”—as long as it doesn’t affect anyone’s job, reallocate resources, or otherwise threaten the occupational interests of the adults running the system. Most changes of real consequence are therefore off the table. The party specializes instead in proposals that involve spending more money and hiring more teachers: reductions in class size, across-the-board raises, and huge new programs like universal preschool. These efforts probably have some benefits for kids. But they come at an exorbitant price, both in dollars and opportunities forgone, and purposely ignore the fundamentals that need to be addressed.

What should the Democrats be doing? Above all, they should be guided by a single overarching principle: do what is best for children. As for specifics, here are a few that deserve priority.

They need to get serious about accountability. The unions want it eviscerated, and many Democrats are eager to sing their tune: denouncing No Child Left Behind, excoriating standardized tests, opposing consequences for poor performance, and demanding more money.

Real accountability is about standing up for children. The adults are supposed to be teaching kids something, and accountability demands hard, objective measures—through sophisticated testing and information systems— of how well they are doing. Good performance needs to be rewarded, but poor performance needs to be uprooted. Schools need to be reconstituted, teachers need to be moved out of the classroom, and jobs need to be put at risk— because if they aren’t, children continue to be victimized.

Democrats also have to get serious about school choice. The unions oppose it because they don’t want one student or one dollar to leave the regular public schools, where their members teach. So the Democrats have been timid and weak in putting choice to productive use—even though their constituents are the ones trapped in deplorably bad urban schools whose futures are being ruined and who are desperate for new educational opportunities.

If children were their sole concern, Democrats would be the champions of school choice. They would help parents put their kids into whatever good schools are out there, including private schools. They would vastly increase the number of charter schools. They would see competition as healthy and necessary for the regular public schools, which should never be allowed to take kids and money for granted.

The Democrats also need to get serious about the downside of collective bargaining. They have long looked the other way as labor contracts impose page after page of onerous work rules—basing teacher assignments on seniority, for example, or making it virtually impossible to dismiss anyone. These rules fundamentally shape, and distort, the organization of schooling. Because of them, schools are organized to promote the interests of adults, not children.

The Democrats are a party of noble ideals, with a proud history of fighting for the underdogs. So far, their Faustian bargain with the unions has prevented them from living up to what they truly believe. Yet there are two reasons for optimism.

The first is Barack Obama, the party’s new leader. He has hinted at a willingness to break with the teachers’ unions, and his massive success at decentralized fund-raising and recruiting volunteers may enable him to do that. He has talked—vaguely—about removing mediocre teachers, holding educators accountable, basing pay on performance, and expanding school choice. But his positions on these scores are hedged about with qualifications, and his education agenda as a whole is mainly (not entirely) a laundry list of typical Democratic ideas.

The second basis for optimism is that two new groups that speak for disadvantaged kids, the Education Equality Project and Democrats for Education Reform, have finally stood up within the party and spoken out against the unions. Including key figures such as Cory Booker, Joel Klein, Michelle Rhee, and Al Sharpton, these groups want real accountability, they want more school choice, they want to end restrictive work rules—and they insist that children come first. That internal rebellion is one of the most important developments in modern American education.

It all boils down to a simple question. Will President Obama have the courage to unite with the rebels inside his party, champion the interests of children over the interests of adults, and be a true leader who really means it when he talks about change? We can only stay tuned. And have the audacity of hope.