- Energy & Environment

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- State & Local

- California

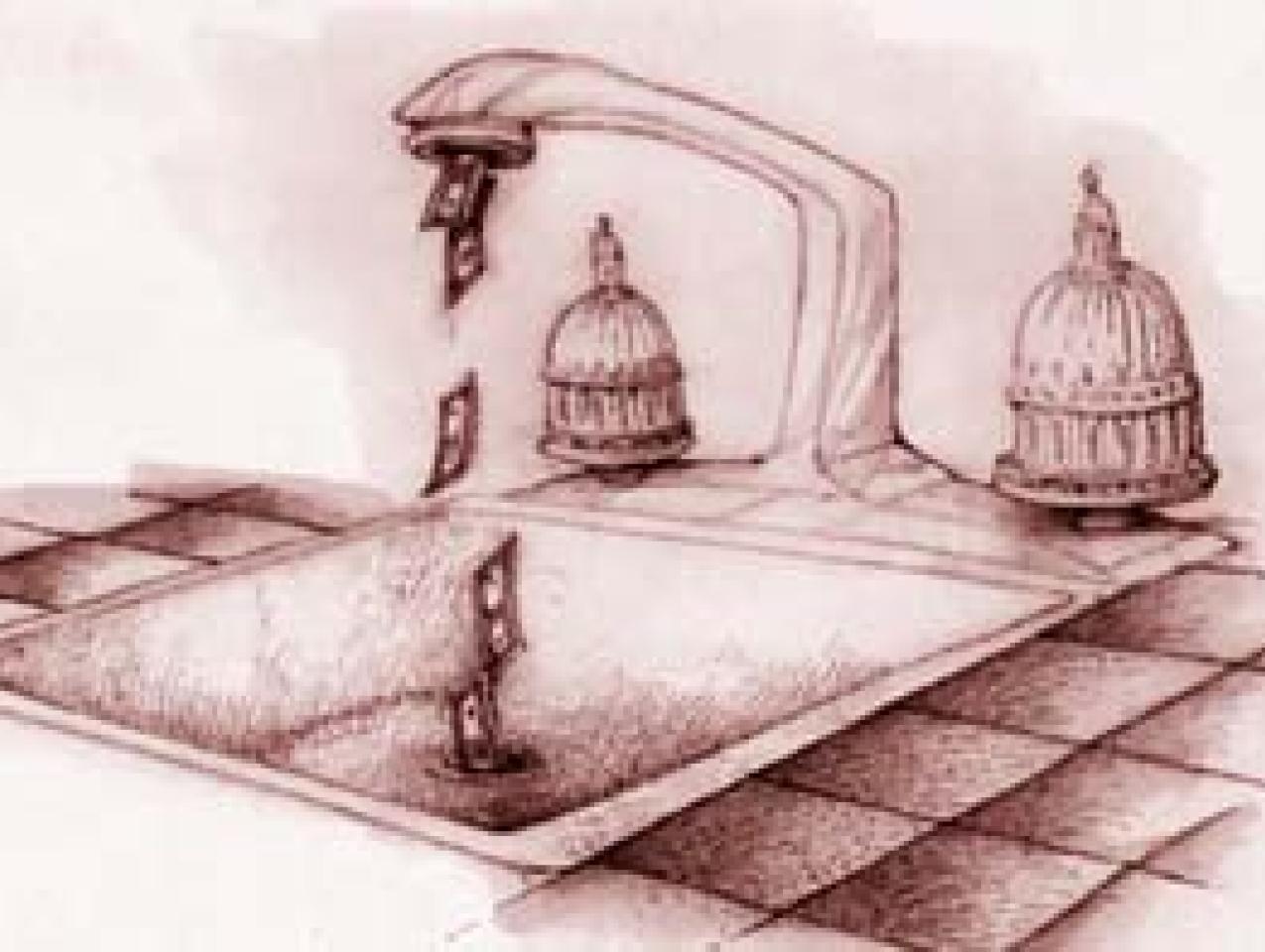

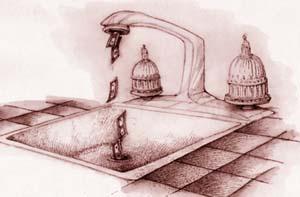

Just as El Niño rains are sending rivers over their banks, the Resources Agency of California has released a draft of the California Water Plan predicting statewide shortages early in the next century. Doomsday predictions are typical of such reports, as are the calls for bureaucratic planning to correct the problem. Neither the predictions nor more bureaucracy would be necessary if the plan put more emphasis on water markets.

Here is the essence of the report’s findings. Between today and 2020, population growth is predicted to increase California’s water shortfall to 2.9 million acre-feet in an average year. (An acre-foot is approximately the amount used by a typical family each year.) The plan concludes that “Californians cannot afford to sustain future water shortages of this magnitude.” Indeed!

So what is the solution? More concrete and steel and more bureaucratic controls. David Kennedy, director of the Department of Water Resources, calls for “water management options” including new storage and conveyance facilities, water recycling and conservation, water transfers, local agency surface water and groundwater supply projects, and desalination, to mention a few.

These management options suffer from two major problems. First, they lack any meaningful sense of economic and environmental costs and benefits. Second, they ignore the obvious solution—water markets—that is catching on in the West and around the world.

Supply-side solutions including more storage and conveyance facilities, recycling, and desalination are common in state water plans, despite the fact that they seldom pass economic benefit-cost muster. A classic example of government water economics comes from Utah, where it will cost $300 per acre-foot just to deliver water to farmers from the recently funded Central Utah Project, never mind the sunk costs of dams already built. The same acre-foot of water will produce crops worth $30 but cost farmers only $8. Is anyone surprised that the Utah congressional delegation was able to move this project forward, and is there any question whether California projects will be any different? Water may not run uphill on its own, but it surely gushes uphill under political pressure.

Water may not run uphill on its own, but it surely gushes uphill under political pressure.

At costs as high as $2,000 per acre-foot, desalination does not make good economic sense; recycling does not look much better with costs as high as $500 per acre-foot.

The second major problem is that a search of the plan’s summary bulletin revealed not a single reference to water markets or water prices. Yet markets provide the surest way to encourage water use efficiency and eliminate shortages.

If there are water shortages, it will be because water prices are too low. Data from every corner of the world show that a 10 percent price increase reduces urban water use by as much as 12 percent and farm water use by 20 percent.

Consider two of the success stories of water marketing:

- When the state of California experimented with its Drought Emergency Water Bank in 1991, an offer price of $125 per acre-foot yielded offers to supply water in excess of the 500,000 acre-feet that the state was trying to obtain.

- In the drought year of 1987–1988, water trading between the Australian states of New South Wales and South Australia involved more than 1 million acre-feet and, by improving water use efficiency, increased farm incomes by an estimated $17 million.

Trading between California and Arizona for Colorado River water could provide similar benefits. The Central Arizona Project (CAP) pumps water 3,000 vertical feet from the Colorado River to agricultural users, who pay between $17 and $41 per acre-foot. Even at these subsidized prices, Arizona users demand only 55 percent of the 1.5 million acre-feet they are guaranteed by the Colorado River Compact. Moreover, the project operates at a loss of $24 million a year. Much of the remainder is being captured by California and Nevada, but the supply is certainly not secure.

Why not encourage some interstate trading between Arizona and California?

A price of $140 per acre-foot would enable CAP to cover its losses, a price far below the $150 being paid in California and Nevada for water from irrigation districts and even farther below the $1,600 for desalinated water. Arizona has expressed interest in changing the decree that governs water use among the Colorado River states to allow leasing of unused water. California ought to jump on this bandwagon.

In 1982, when the Peripheral Canal Initiative was defeated by California voters, Thomas Graff, general counsel for the Environmental Defense Fund, raised a prophetic question when he asked, “Has all future water-project development been choked off by the new conservationist-conservative alliance?” The California Water Plan suggests not, but the plan is open for comment. Now is the time for a “conservationist-conservative alliance” to make itself heard and put some market sense into California’s water problems.