In 2013, the Dallas Safari Club worked with Namibian wildlife officials to auction a hunt of a black rhino, the most endangered of the rhino species. They expected to raise as much as $1 million from the auction with 100 percent of the proceeds going to rhino conservation efforts. Moreover, the rhino to be hunted was a cantankerous old bull, no longer of breeding age, which was harassing and even killing other rhinos.

Nonetheless, animal rights groups viciously attacked the Dallas Safari Club even to the point of threatening bodily harm to club leaders and anyone who bid on the hunt. Not surprisingly the auction brought far less than $1 million—$350,000. Further opposition from the animal rights groups pressured the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to disallow importation of the trophy on the grounds that the Endangered Species Act protects endangered species even if they reside outside our borders. Finally, in 2015 the USFWS recanted and issued the importation permit, and the hunter bagged his rhino.

This raises the question: Is hunting good for wildlife conservation? To understand why the answer is unequivocally yes, consider the conservation story of Marty Anderson, a Hoover Institution board member.

Kenya banned hunting completely in 1977. The result of the ban is no better illustrated than on Galana Ranch, a property almost as large as Yellowstone Park. The Galana story is one that should be in every hunter’s arsenal for responding to anti-hunters because it illustrates what hunting can do for wildlife and what happens when hunting is banned. (Details of this story can be found in Galana: Elephants, Game Domestication, and Cattle on a Kenya Ranch.) Leaving emotion aside, hunter-conservationists must continue to provide evidence, not rhetoric, that hunting is an environmentally sound practice—something that anti-hunting zealots rarely do. Through examples such a Galana, hunters can drive home the message that hunting is sustainable conservation.

We pick up the story of Galana Ranch in 1960 when Martin Anderson ventured to the Dark Continent on his first hunt. He was lured to Africa by the sights and sounds familiar to all who have read Hemingway or Ruark. But his hunting passion was quickly directed to wildlife conservation.

In 1960, Kenyan wildlife was abundant and its politics were turbulent. The Mau Mau Rebellion signaled the end of colonial rule, leading most colonialists to ask one another, “Have you sold your land yet?” As a retired Marine, lawyer, and entrepreneur, however, Anderson saw Kenya' s challenges as an opportunity.

Having whetted his appetite by investing in a 1,500-acre farm, Anderson took a giant leap into sustainable wildlife conservation when he bid on and won a 46-year lease on the 1.6 million acre Galana Ranch on the border with Tsavo East National Park.

As an astute businessman, financing the $100,000 winning bid and finding local management partners was not a problem. But Anderson had to ask himself. “Was developing this virgin land the right thing to do? Would we destroy it for the elephant and the Waliangulu [bushmen]?” Ultimately, he pursued a strategy which incorporated cattle ranching and hunting so as to generate income and preserve the conservation values.

Anderson and his partners developed pipelines, water points, roads, airstrips, and lodges, all of which contributed to the financial and conservation bottom lines. They generated revenues from 16,000 cattle and from hunting every species from the big five—rhino, elephants, Cape buffalo, lion, and leopard—to the smallest duikers. Wherever possible, they employed native Kenyans in their cattle and wildlife operations.

One of the first management challenges on Galana was to find a way to reduce elephant hunting by bushmen. Although they hunted only with poison-tipped arrows launched from wooden longbows with 100 pound draw weights and only for meat (not ivory), the bushmen were so proficient that they were decimating the Dabassa elephant herd, which roamed Galana and Tsavo East. Anderson reported that one search “between the Galana and Tana Rivers, discovered the carcasses of about 900 elephants,” including “352 tusks, weighting more than 6,500 pounds.” Rather than trying to force them to stop killing elephants, Anderson incorporated the Waliangulu into his elephant management program, allowing them to cull elephants on a sustained yield basis.

For ten years, Galana made profits from safari hunting based on sound conservation principles. Anderson’s success gives meaning to the old rancher adage, “If it pays, it stays.”

Unfortunately, Anderson and the other Kenyan hunter-conservationists ultimately lost out to so-called animal “welfare” activists. In May of 1977, anti-hunters succeeded in banning all “legal" hunting in Kenya. Without hunting, wildlife on Galana ceased being an asset. Hunting had provided a major source of revenue for sustainable, profitable, private conservation. Thanks to the wildlife activists, though, there were no revenues and no hunters or guides in the field to police against poaching. Not surprisingly, poachers slaughtered more than 5,000 of the 6,000 elephants Anderson and his partners had conserved.

Perhaps more importantly, hunting provided native people with incomes and with meat, giving them an incentive to be part of the conservation effort. With wildlife all but gone, the government proposed in 2013 to put 1.2 million acres of the original ranch under irrigation, a project that will not be sustainable.

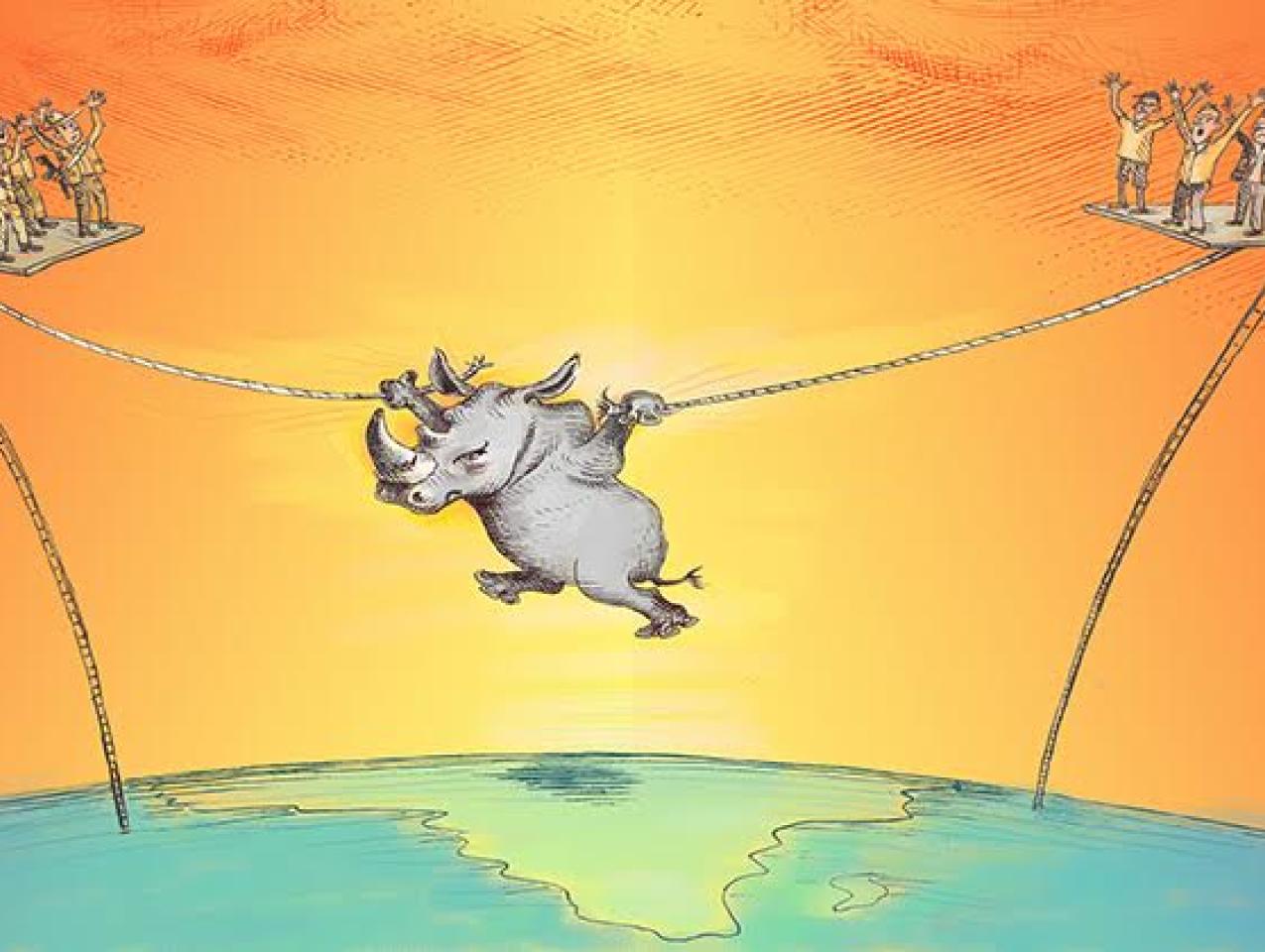

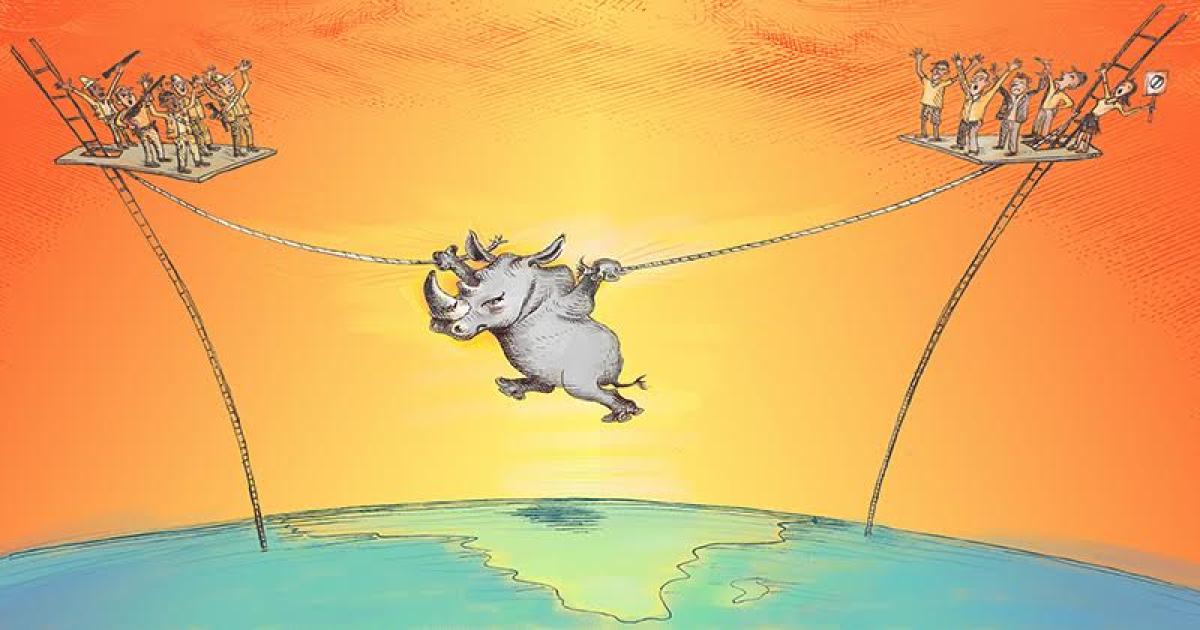

Anderson summarized the hunting/anti-hunting debate as follows: “Sadly, the often emotional rhetoric between the hunting and the non-hunting communities obscures a large area of shared agreement. Both camps want passionately to preserve animal populations. Both sides know that wildlife needs protection from a shrinking wildlife habitat and a growing human population.” The difference is that Anderson and his hunting clients were actually making wildlife and its habitat a sustainable asset.

In 2006, I was invited to Kenya to participate in a conference debating whether to resurrect Kenyan hunting. One of the sponsors of the conference, IFAW (International Fund for Animal Welfare), packed the first rows of the auditorium with anti-hunting advocates. My role was to debate famed Richard Leakey, who was the director of the Kenya Wildlife Service when the hunting ban was implemented. Given his reputation and the sympathetic audience, I would have preferred facing a Cape buffalo with my bow as I had done a few years before. Leakey took the podium first as his allies listened intently. He opened saying “If anyone here thinks there is no hunting in Kenya, he is wrong. The ‘hunting’ is illegal hunting for bush meat, and it is decimating wildlife outside the protected areas.”

The comparison of data between Kenya, where hunting was banned, and Botswana, where it was allowed until 2014, and the Galana story demonstrate that hunting is the engine of profit that allows sustainable conservation. The Kenyan elephant population fell precipitously between 1973 and 2013 while the Botswanan elephant population skyrocketed. Seizures of illegal ivory were nearly five time larger in Kenya than Botswana between 1989 and 2011. And Kenya accounted for more than 15 percent of all illegal ivory seizure in Africa over the past two decades compared to just over 3 percent for Botswana. These data show that the prohibition of hunting kills the goose that lays golden eggs for the people of Africa and for the wildlife.

With such evidence, you would think the debate would be over, but the anti-hunting groups claiming to represent “animal welfare” continue their rant. While it is true that both hunters and anti-hunters want to preserve wildlife, as Anderson said, only hunters are doing something about it, and they have the evidence to prove it.