- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- Security & Defense

- Terrorism

Since time immemorial, rogue entities have flouted the rules imposed by major states or imperial structures to attain their ends. In the modern context, rogue states show contempt for international norms by repressing their own populations, promoting international terrorism, seeking weapons of mass destruction, and pursuing militant policies of nonalignment. Although the weapons and strategies employed by rogues have evolved over the centuries, their inevitable lapse into political oblivion or subservience to a stronger power has remained a historical constant that endures.

|

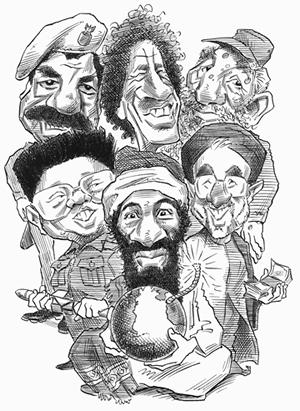

| Illustration by Taylor Jones for the Hoover Digest.

|

A cursory examination of the rich historical role rogues have played through the ages can help advance our understanding of their modern counterparts. This essay does not claim to be exhaustive or imply that today’s rogues are exact historical analogs to their ancient cousins. It does, however, seek to highlight perennial patterns of rogue behavior that are clearly resurgent today while suggesting more effective policies by which the United States might meet this threat.

Historical Overview

The pages of history—both ancient and modern—are replete with examples of rogue powers that were anything but inconsequential to the geopolitical balance of their day. The assistance of the Gauls, to take but one illustration, played a crucial role in Hannibal’s drive across the Alps into the Italian peninsula—a campaign that shook the Roman Empire to its very foundation. With the eclipse of the Pax Romana, rogue entities moved to the fore as northern Europe experienced the depredations of the Vikings while the Mediterranean became a hotbed of piracy. As the medieval age gave way to the age of exploration, the larger European powers continued to court rogues as the struggle for hegemony in Europe grew into a worldwide contest. The late sixteenth-century maritime standoff, for example, saw the European powers actively encouraging private shipowners to attack enemy vessels on the high seas.

The European expansion of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries did not spell the end of the rogue phenomenon. In fact, ironically, two hallmarks of the modern era—the unbridled advance of technology and virulent strains of nationalist and socialist ideology—provided outlaw regimes with powerful new mechanisms for maintaining their rule at home and manipulating the international system abroad.

Early Twentieth-Century Rogues

The early twentieth-century international landscape also manifested the rogue phenomenon in rich variety and profusion, with one notable break with the past—the infusion of ideological fanaticism.

The Bolsheviks considered the seizure of power in backward Russia a prelude to worldwide revolution. Considering such strident revolutionary doctrine, it is little wonder that Washington isolated Soviet Russia for a decade and a half. Not until the rise of militarism in Asia and Nazism in Germany did the administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt restore diplomatic relations with a Moscow gazing apprehensively askance at the same phenomena.

The post–World War I era witnessed the birth of another pariah state in defeated Wilhelmine Germany. Riding a wave of political and economic crises, the twentieth century’s ultimate rogue, Adolph Hitler, came to power and transformed a modern, civilized nation into a genocidal military machine bent on mass murder and world domination. The Allied defeat of Germany eliminated a menace but failed to erase the rogue role model.

The cataclysmic results of the Second World War often obscure the fact that before its outbreak a revolutionary Marxist vanguard and a reactionary, Junker-inspired military state found common cause in mutual isolation. Denied membership in the League of Nations, Weimar Germany and Bolshevik Russia cooperated covertly on military-technical matters throughout the interwar period. Knowledge of this unholy (and counterintuitive) alliance occasionally surfaced, most sensationally in the 1939 Nazi-Soviet pact. The latter half of the twentieth century would bear witness to similar marriages of convenience–nihilistic codependencies that became even more dangerous with the advent of weapons of mass destruction.

Cold War Nuclear Pariahs

During the Cold War, the world accorded pariah status to states such as Israel, South Africa, South Korea, and Taiwan for developing, or even hinting at developing, nuclear weapons. Despite divergent political and economic systems, these four pariahs shared one overriding concern: national survival in regions where the conventional military balance was tilted against them. Their experience warrants mention because it serves as a prelude to the nexus between pariah regimes and the weapons of mass destruction of the post–Cold War era.

In time, though, South Korea and Taiwan took shelter under the American nuclear and conventional arms umbrella rather than pursue their own atomic programs. As excluded states often do, South Africa and Israel overtly cooperated in conventional military activities and perhaps clandestinely on nuclear matters. Pretoria, however, voluntarily and unilaterally dropped its nuclear capability in 1993. Although Tel Aviv officially denies it, Israel is believed to have atomic weapons.

Cold War Proxies

Washington and Moscow fought the Cold War in political, economic, and diplomatic arenas. In addition to the nuclear standoff, each employed blocs and proxies to hamstring its opponent–the United States through NATO and a string of global security guarantees, Moscow through its direction of the Warsaw Treaty Organization and a host of liberation movements in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Many of the proxy states that embraced terrorism during this time became synonymous with rogue states in the post—Cold War period.

Moscow’s sponsorship of national liberation movements racked up a string of victories in the Third World. But it was Cuba that became Moscow’s archetype proxy state, instigating or supporting insurgencies in Africa and Central and South America. Not all of Moscow’s Third World proxies embraced Marxism. Outright dictatorships such as Iraq, Libya, and Syria had little affinity for Marxist doctrine–their game was power, antipathy to the United States, and hatred of Israel. Post-Shah Iran fell into this category. Iran had long resisted Russian encroachments on its territory, and the country’s Islamic clerics were repelled by Moscow’s espousal of godless communism. Still, Iran’s sponsorship of terrorism and its strident anti-Americanism paralleled Moscow’s designs.

|

During the 1990s, the leaders of rogue states were seen as irrational actors who formed policy based on nihilistic impulses rather than on national interests. Today’s rogue states, by contrast, generally do pursue policies firmly based on national interests. |

Post–Cold War Rogues

The immediate post–Cold War era witnessed the first official application of the term rogue state when President Clinton spoke in Brussels about the "clear and present danger" that missiles from "rogue states such as Iran and Libya" posed for Europe. The shift away from the bipolar competition of the Cold War goes a long way toward explaining why the Clinton administration found it so difficult to come to terms with states that defied international norms, sponsored terrorism, and pursued the acquisition of mega–death weapons. But the lack of precedence notwithstanding, the administration also misread the very nature of the beast itself.

In the initial years following the end of the Cold War, rogue states—particularly North Korea and Iraq—acted unpredictably and criminally in the absence of great-power patrons. This behavior gave rise to the assumption that rogues were simply irrational actors who formed policy on nihilistic impulse rather than on rational interest. By the new millennium, however, these initial assumptions had fallen by the wayside, modified in part by their rulers’ more subdued public pose. Although rogues still possessed the capacity for mischief, their actions seemed grounded in a rational self-interest that was amenable to negotiation. Their international isolation, moreover, had decreased substantially.

Cuba and Libya: Rational Survivalists

Cuba has become less extroverted in its practice of terrorism, but it has kept up its anti-U.S. rhetoric and facilitated the shipment of narcotics onto American shores. Unlike North Korea, Cuba has not attempted to build nuclear weapons or export rockets. It has, however, imitated its Asian counterpart by looking to China for selective support. During the early 1990s, Castro and President Jiang Zemin exchanged visits, and Chinese defense minister Chi Haotian headed a military delegation to Cuba in 1997. As European and Canadian business dealings and tourism eased the American economic embargo, Beijing furnished economic and military aid in return for an eavesdropping post near the United States through its financing of the Terrena Caribe Satellite Tracking Base and other facilities.

In 1999, after decades as a hotbed of terrorism, Libya’s Muammar Qaddafi turned over two suspects in the 1988 downing of Pan American flight 103 for trial in the Netherlands. Additionally, Qaddafi financially compensated the families of the French victims killed when their airliner was blown up over Africa in 1989. Libya also agreed to pay a $1 million ransom for each of the 12 foreign hostages held by Muslim rebels in the southern Philippines in mid-2000. These and other actions spawned press accounts of how Qaddafi craved respectability and hungered for acceptance from former foes. Qaddafi’s reversal, in part, derived from Libya’s need to have sanctions lifted in order to revive its depressed economy and export its oil reserves for hard currency. Nevertheless, the change in outward appearance was dramatic.

North Korea: From Rogue to Tame Partner?

During the 1990s, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) loomed as the quintessential rogue state. A rusting relic of the Stalin period, the DPRK within a few years of the Soviet Union’s demise looked poised to follow its mentor onto the ash heap of history.

Faced with evidence in late 1992 that the DPRK was cheating on the Non-Proliferation Treaty, the Clinton administration chose negotiation over deterrence through an elaborate agreement with North Korea. Under the Agreed Framework, in return for two light-water reactors funded by Japan and South Korea, Pyongyang promised to halt its nuclear weapons program. The White House touted this agreement as creative conflict resolution; critics greeted it with skepticism, and their doubts were shortly confirmed.

On August 31, 1998, Pyongyang test fired a long-range missile that traveled over northern Japan before plunging into the Pacific. Although North Korean officials claimed that the solid-fuel missile had been fired in an attempt to place a satellite in orbit, observers in Japan, South Korea, and the United States concluded that the DPRK was on the road to building ICBMs capable of hitting the American continent. Soon thereafter Pyongyang announced a suspension in missile launches in return for continued foreign aid from Japan, South Korea, and the United States.

In 2000, after a series of meetings between DPRK leaders and former U.S. secretary of defense William J. Perry—and the historic June summit between the North and South Korean leaders that followed—Washington lifted most of its economic sanctions against the DPRK. Other conciliatory steps followed, including family visits, joint economic enterprises, and new North-South communications links. Like Libya, North Korea also turned a softer face to the outside world.

Despite an apparent thaw on the peninsula, however, the DPRK has persisted in bandit-state antics and outright criminal pursuits such as trade in narcotics and counterfeiting U.S. currency. Most worrisome, though, has been its trafficking in missile technology to other rogue states such as Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, and Syria.

Despite Beijing’s long-standing denials, outsiders note that China has influenced the DPRK’s behavior more than any other state. After all, China spent blood and treasure repelling the U.S. intervention during the Korean War. In the postwar period, China has continued to provide Pyongyang with material and technical assistance, including access to off-the-shelf electronics for weapons and missile development. Although Beijing claims a lack of influence over its difficult neighbor, Kim Jong Il’s visit to the Chinese capital just before the landmark North-South meeting in mid-2000 told a different story.

With great diplomatic astuteness, Pyongyang managed to insinuate itself into the American consciousness through nuclear blackmail. The DPRK circumvented South Korean objections and achieved direct contact with Washington. The North Korean stratagem resulted in U.S. shipments of food through the U.N. World Food Program and, ultimately, an end to most economic sanctions. Far from irrational, North Korea’s leadership played a weak hand with commensurate skill.

Iraq: From Rogue to Brother State

Iraq’s trajectory parallels North Korea’s in many regards. At the close of the Gulf War, Iraq stood isolated (both internationally and within the Muslim world) and hemmed in by U.N. sanctions and restrictions, such as authorized no-fly zones in the north and south.

Still, Iraq dug in its heels, forcing Washington to bolster its military presence in the region and revisit the use of force through punitive air strikes on several occasions. Although this no-war, no-peace formula persists to this day, major cracks have appeared in the anti-Hussein coalition as former enemies have rushed to trade with and travel to Iraq.

The withdrawal of the U.N. Special Commission (UNSCOM) in mid-1998 left Saddam Hussein free to develop weapons of mass destruction without risk of public exposure. While Hussein lavished oil revenues on palaces and resorts for his family and cronies, international attention shifted from weapons violations to sympathy for the plight of Iraq’s suffering civilian population.

The heightened anti-Americanism generated throughout the Muslim world as a result of renewed Israeli-Palestinian fighting in late 2000 also played into the hands of Baghdad. Embracing the Palestinian cause, for the first time since the Gulf War Iraq found itself invited to the Arab League summit in October. Soon after, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Oman, and Qatar resumed diplomatic relations with the Iraqis.

The Undeclared Rogues

Branded rogues like Iraq and North Korea nabbed the most attention in the 1990s, but the early post—Cold War period saw other marginal, brutal, and dictatorial regimes come to power. Although they may have eschewed weapons of mass destruction, these states showed no qualms about spreading terrorism and murdering large numbers of their own citizens. Their governments, however, escaped being branded as roque states, partly because they did not cross the diplomatic line demarcating internal criminality from the acquisition of nuclear or biological weapons.

Afghanistan has somehow avoided the State Department’s list of terrorist states despite harboring America’s most-wanted terrorist, Osama bin Laden. Under Taliban rule, Afghanistan has become a breeding ground for extremists and terrorist groups, who are funded by bin Laden and by the largest sales of opium in the world. The Taliban receives recruits and resources from Pakistan (Afghanistan’s chief patron) and Saudi Arabia in efforts to propagate militant Sunni Islam northward into Central Asiaand the Russian Caucasus and southward into South Asia, including the Philippines.

Slobodan Milosevic’s Serbia (1987—2000) also possessed some but not all of the characteristics associated with a rogue regime. Although Milosevic did not seek to build weapons of mass destruction, his pursuit of "ethnic cleansing" in the cause of a Greater Serbia sparked an ethnic bloodletting throughout the Balkan region. Responsible for nearly 200,000 deaths and about a million refugees, the crimes, fear, and instability engendered by Milosevic can be likened to the practices of fellow rogue leaders like Saddam Hussein and Kim Jong-Il.

Rogue Collusion

Because of ideological, political, and economic disparities, in the past rogues were classified as sui generis and treated on a case-by-case basis. The logic behind this policy was and remains sound. There is a galaxy of difference between North Korea and Iraq. Still, mounting evidence shows that gangster fraternization often bridges cultural cleavages among rogues, thus contravening the notion that these mavericks operate alone or bereft of great-power patronage.

Even implacable enemies collaborate with one another. Despite a legacy of animosity generated by their bloody war in the 1980s, Iran and Iraq have moved toward increased cooperation due to a mutual interest in sanctions busting. Baghdad also dispatched officials to help Serbia weather the Kosovo bombing campaign. According to press accounts, Serbia permitted North Korean observers to assess the NATO bombing in order to prepare their country for a potentially similar conflict. China assists Sudan’s oil exploitation and deploys security personnel to protect the oil-carrying pipelines. Iran, arguably the most independent of rogue states, has entered into realpolitik cooperation with Russia, even though they share little besides common foes.

North Korea’s entire missile program, from launchers to rockets to fuel, bears the mark of extensive Russian and Chinese assistance—often in glaring violation of the Missile Technology Control Regime. This illicit trade in technology reverberates far beyond the Korean peninsula. Cash strapped and desperate for geopolitical leverage, North Korea in turn markets rocket components and scientific expertise to Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, and Syria.

China and Russia now sponsor rogues for commercial and geopolitical reasons rather than ideological objectives. Cold War relationships are being reactivated and arms sales and diplomatic initiatives pursued not only for cash and influence but also with an eye to countering American influence. Unlike the neat symmetry of the Cold War nuclear standoff, today’s security environment is a crazy quilt of "proliferators" and weapons-amassing states, which include not only rogues but also India and Pakistan. The scale, pace, and destination of these transfers portend a dangerous world in the near future.

Back to the Future and the New Security Environment—U.S. Policy Options

Competition between the globe’s major players naturally draws smaller states into the fray. As outcast states and major powers reestablish loose affiliations, the anomaly of the solitary rogue is fading. Throughout recorded history, major players moved pawns to checkmate queens. Global chess in the present era is characterized by attempts to exact concessions from the world’s most powerful state while avoiding head-on confrontation. Subtler than a direct challenge, the proliferation of nuclear or advanced ballistic missile technology by China and Russia achieves this effect by threatening U.S. interests worldwide.

The United States can and must take several steps to recalibrate its policies in order to meet this challenge:

• Because the nonproliferation of weapons of mass destruction is the single most pressing foreign policy issue today, the new administration must acknowledge that arms control treaties will not be effective against big-power—supplied rogues, which ignore international legal codes.

• Washington must redouble its diplomatic exertions to halt the patronage of rogue dictators by Russia and China. As the past decade clearly illustrates, commercial engagement alone is not enough to nudge Moscow and Beijing toward peaceful pursuits.

• Washington must pursue astute diplomacy that divides rogue regimes from patrons and each other. Since circumstances differ with each rogue, the steps taken to neutralize them can vary from covert actions to forms of economic and diplomatic engagement. But whatever the course of action, it must be sustained.

• To hedge against the failure of arms control and diplomacy, American national and theater missile defense systems must become a reality.

During the Clinton administration, the State Department rolled out the term states of concern as a more sanitized rubric for many of the regimes mentioned above. Nonetheless, changing global circumstances rather than departmental fiat will determine whether the term rogue slips from the diplomatic lexicon. Present-day rogues are less isolated than in the years immediately following the Cold War. Isolated rogue states have historically proven to be an anomaly. Their ties to leading powers constitute a more permanent feature of world politics. Today rogue animosity fuels a backlash against the development of the global economy and the spread of democracy. A possible narco-Marxist Colombia or a terrorist-prone Pakistan will search for stronger collaborators just as their rogue predecessors have. What seems unlikely is that small pariahs will for long shun the safety and material benefits that powerful patrons provide.