- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

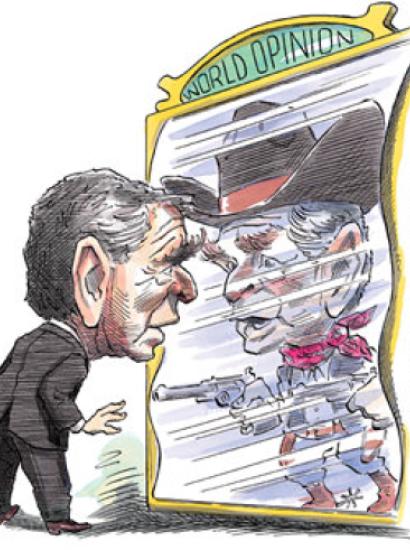

So why is the United States so disliked and resented in the world today?

As Zbigniew Brzezinski said in his remarks at the Hoover Institution in April, there has probably never been a time when there was such a wide gap between our military and political standing in the world. Militarily, American power has never been more dominant. Not only is the United States without peer among potential military challengers, but there is no conceivable coalition of nations that could challenge the military might of the United States today or at any time in the foreseeable years to come. And the military gap between the United States and other relatively powerful and resourceful countries—both our allies and our potential adversaries—is rapidly widening.

Yet the political and moral standing of the United States in the world is in many respects the lowest it has been in decades, at least since the Vietnam War. Most of the governments that joined or endorsed the United States–led war to topple Saddam Hussein did so in defiance of their own public opinion. In Eastern Europe—what Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld hopefully dubbed the “new Europe”—up to three-quarters of the public in most countries were antiwar, and public opinion in some countries even opposed assisting the United States from the sidelines. In many countries we regard as democracies and friends, the majority of the public regards the United States as a problem for the world, not a guarantor of freedom and order.

Anti-Americanism is surging around the world, and in sharp contrast to the Cold War era it is no longer the exclusive domain of the Left. In South Korea, it helped propel a trailing presidential candidate to victory in December 2002. In Western Europe it has infiltrated the political right as well and has even become entangled with anti-Semitism. In Eastern Europe, anti-Americanism shows signs of converging with anti-market and anti-democratic sentiments into a potent new reactionary brew. In remarks to the National Endowment for Democracy in April, Ivan Krastev, director of the Center for Liberal Strategies in Bulgaria and one of Eastern Europe’s most astute political analysts, warned that anti-Americanism risks becoming an empty vessel into which can be poured economic frustrations, “nostalgic communism,” and ethnic bigotries. “This is why for us anti-Americanism seen from Bulgaria can be a threat to the democratic agenda itself.”

What drives this new wave of anti-Americanism? Part of it is the inevitable resentment of U.S. power, now that we are the world’s lone superpower. Part of it is envy at our wealth, success, and cultural dynamism. Much of it springs from opposition to our policies, particularly—in the Arab world, the Muslim world more broadly, and to some extent in Europe—our steadfast support of Israel. (Much of this is plain bias against Israel or even anti-Semitism, but there is also a growing global sense that, in tolerating Israel’s relentless expansion of settlements and heavy military measures in the West Bank, U.S. policy has lacked the fairness and balance to which it professes commitment.) A good measure of the resentment, however, stems from the perception that, as the United States has become ever more powerful, it has also become more arrogant, cavalier, and condescending to the rest of the world.

The “new American hubris” is how Hoover Institution senior fellow Timothy Garton Ash—one of the most sophisticated pro-American Europeans—described the tendency among many American foreign policymakers and intellectuals “to celebrate and exaggerate American power,” in an important essay in the New York Times Magazine on April 27. To be sure, the United States has never shied away from unilateral military action when it believed its vital interests were at stake. But, since 1945, American leadership of the free world has been based on a shared vision of a common global project and on a dense array of alliances with other free states, especially in Europe. Perhaps the most alarming aspect of the new drift in world affairs is the rapid deterioration of the Atlantic alliance and the possibility of an enduring rupture in the shared values and strategic purpose that have for more than half a century bound Europeans and Americans together in the pursuit of global freedom, order, and economic openness.

One of the first instincts of Americans when they confront anti-Americanism is to think, “This must all be some misunderstanding. Once they know us and understand us, surely they will like us.” In our posture toward the Middle East, this instinct has driven the rapid expansion of new radio broadcasting efforts in Arabic and Persian to disseminate American music, as well as ideas and information. Now, plans are under way to organize an Arabic-language all-news television station, beamed to the Middle East, to counter the overwhelmingly anti-American and anti-Israeli tone of several existing Arabic channels, most prominently, Al Jazeera. These initiatives in public diplomacy and public broadcasting will help. But they cannot substitute for a strategy. And they do not relieve us of the urgent need to reflect upon our tone, our means, and our priorities.

Surging anti-Americanism has become a serious problem for our national security. It threatens to undermine cooperation in the war on terror, to create a permissive climate for attacks on American citizens and interests, and to frustrate other crucial strategic objectives such as the lowering of trade barriers, the expansion and consolidation of democracy, and the disruption of global criminal networks. How can we turn back the rising tide of anti-Americanism? Our security depends not only on our being extensively engaged with the world on all these fronts but on our being seen to engage in a way that invites partnership and cooperation rather than dictation and domination.

Here are some guidelines that can aid us in this mission:

1. Adopt a less arrogant tone. We can take pride in the power, courage, and efficiency of our armed forces and in American values. But to be effective in the world, we need to see ourselves as others see us and thus adopt a posture and rhetorical tone that are less boastful, arrogant, flippant, and self-congratulatory. Statements directed to the American public are also heard around the world. We need to do more to acknowledge that, even as it liberates, our military action causes pain and death and imposes huge postwar responsibilities on us. We need to recall President George W. Bush’s own stated philosophy from the 2000 presidential campaign: that the United States needs to speak and act on the world stage with greater humility. A century later, we would still do well to follow Teddy Roosevelt’s famous dictum (borrowed from a West African proverb): “Speak softly but carry a big stick.”

2. Respect nationalism as a political force. The people of every nation want to feel proud of themselves as a nation, and nationalism is a force we have to acknowledge and accommodate in many places, even as we try to steer it toward positive ends. This means treating rising powers such as South Korea with dignity and respect. It means understanding the historical grievances and aspirations of other nations that may shape but also transcend the policies of any particular government or regime. It requires finding ways to draw sharp distinctions between governments we think are irresponsible and societies we want to engage and embrace.

In the most recent World Values Survey, 92 percent of Iranians said they felt “very proud” of their nationality. When we condemn the oppressive Iranian regime of the ayatollahs, we must be careful at the same time to affirm our solidarity with the Iranian people and our esteem for their culture, history, and rightful place in the region and the world. As Minxin Pei argues in the May/June issue of Foreign Policy, we need to recognize that other countries do not like being dictated to by the United States and that, when we are domineering, we tend to alienate the very people we are trying to rally to our side.

3. Do a better job of consulting with and engaging our democratic allies. We cannot on our own forge enduring solutions to the global challenges of terrorism, weapons proliferation, drug trafficking, money laundering, poverty, AIDS, trade barriers, sluggish growth, and so on, for they require cooperative solutions that coordinate the policies and pool the resources of the world’s most powerful countries—in particular, the wealthy democracies of North America, Europe, Japan, and Australia but also the emerging powers of the world. And in crafting policy responses, we need to engage as well the developing and conflict-ridden countries from which many of these problems emanate. Of course, we do have some international institutions that are making progress toward cooperative solutions. The World Trade Organization is one. The Global Fund to fight HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases could become another. But we need to revitalize the G-8 summit and other instruments for crafting common approaches to these problems.

4. Commit to a long process of nation rebuilding in Iraq and Afghanistan. With victory in war comes responsibility. We now have a responsibility both to ourselves—to ensure that Iraq and Afghanistan do not once again threaten the United States and our allies—and to these two countries to ensure that decent, humane, lawful, effective, and hopefully democratic states are reconstructed. In each case, that is going to require the presence of large numbers of international troops for probably several years to ensure political order and a huge commitment of civilian postwar reconstruction.

In Afghanistan, a much larger peace implementation force is needed to face down the warlords who have created their own private, de facto states within various regions and to stop the Taliban from regrouping, as it is now apparently doing. In Iraq, more than 150,000 international troops may be needed for the next two years and a heavy international security presence for several years beyond, until a new Iraqi state (and army) fully establishes its democratic form and authority. The scope and likely duration of these burdens require their extensive internationalization. On the security side in Iraq, the military occupation should be gradually transformed from an Anglo-American to a NATO force.

5. Be more consistent in promoting freedom and democracy. If we are going to be liked and respected again in the world (not just feared and deferred to), we must be about something more than the use of force to defend against threats to international security. We need to commit to positive endeavors that reflect universal values. Two values around which we can revive our political and moral standing in the world are democracy and development. We have done much in the past two decades to promote democracy and freedom, and this continues to be a major purpose of our international engagement. However, we need to do more, and more collaboratively, to project this commitment consistently and to thereby convey that it is not just a cover for unseating governments that are unfriendly to the United States. Our efforts to promote democracy, constitutionalism, and human rights, both through diplomacy and through various assistance programs, tend to ring hollow and invite suspicion when they select some countries and regions and ignore others. Of course, we have strategic interests in a lot of places. We need the cooperation of the governments of Pakistan, Uzbekistan, and Egypt in the war on terror. But, by the same token, they need our cooperation and support as well. We need to quit selling short our own leverage and influence and speak up more forcefully for the defense of human rights and the advocacy of long-term, real democratic change in these strategically important countries. We need to be seen to be faithful to our own principles if we want other countries to take them seriously.

6. Lead a new, smart campaign for international development. The international community has made great progress in reducing poverty and raising incomes and levels of health in many countries around the world. But several dozen countries (especially in Africa) remain mired in very deep poverty, and the growth performance of many middle-income countries remains far below what they are capable of. The most common underlying obstacle to development in these countries is bad governance, which fails to guarantee property rights and to use public resources to generate public goods. Rather, countries’ developmental promise is drained away in corruption and lawlessness that discourage investment and foster political violence, repression, and state failure.

The Bush administration has taken a daring conceptual lead in development policy by proposing a new Millennium Challenge Account (MCA) that seeks to encourage and reward good governance for development by increasing annual U.S. development assistance by $5 billion (to be phased in over the next three years). This entire new increment of annual aid is to be allocated to a small group of lower-income countries that will compete for it on the basis of three broad criteria: ruling justly (including respecting democracy, freedom, transparency, and the rule of law), investing in people (through spending on education and basic health), and promoting economic freedom. With the costs of the Iraq war and postwar engagement mounting and the pressure on the U.S. budget deepening, the fate of the MCA is not yet clear. It is vital that this initiative be fully funded and that the United States work with its fellow donors to institutionalize good governance as a core principle of all international development policy. As with the MCA, states that govern responsibly and accountably should be tangibly rewarded, but governments that are corrupt and abusive should not be bailed out of their larceny with continued international largesse. Increasingly, donor governments and institutions such as the World Bank understand that corrupt, abusive, lawless, and unaccountable governance is at the heart of development failure. We can lead a campaign to improve and reward governance, and thereby relieve poverty, if we are willing to invest new resources ourselves and commit to imaginative programs such as the MCA.

We, as Americans, continue to see ourselves, as Ronald Reagan famously reminded us, as “a shining city on a hill.” We are a beacon of freedom in the world, a bulwark against aggression and tyranny, and, by and large, a generous nation that has not used its power for its own imperial aggrandizement. But, increasingly, that is not how the rest of the world sees us. Where we see restraint, they see imperialism. Where we see idealism, they see arrogance. Where we see engagement, they see domination. What they see becomes a consequential reality, however distorted. And that reality now threatens our ability to shape the kind of world we want to live in.

The instruments of hard power have their limits in shaping the world. We cannot invade and occupy every country that may pose a threat to our security. Indeed, with our hands more than full in Iraq and Afghanistan, we probably cannot handle even one more venture of that kind right now. Quite appropriately, we will continue to use military force, intelligence, covert action, and law enforcement to capture, contain, monitor, preempt, disrupt, and bring to justice terrorists around the world. But all that addresses only one aspect of the danger we face. We need to shape a world in which people do not become terrorists and in which anger and frustration over the unfairness of life is not increasingly directed at the United States. Shaping this kind of world requires mainly the tools of soft power and a tone and a strategy that once again respects and engages our natural partners.