- Budget & Spending

- Economics

- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- Energy & Environment

- International Affairs

- Economic

- Contemporary

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Campaigns & Elections

- State & Local

- Civil Rights & Race

- History

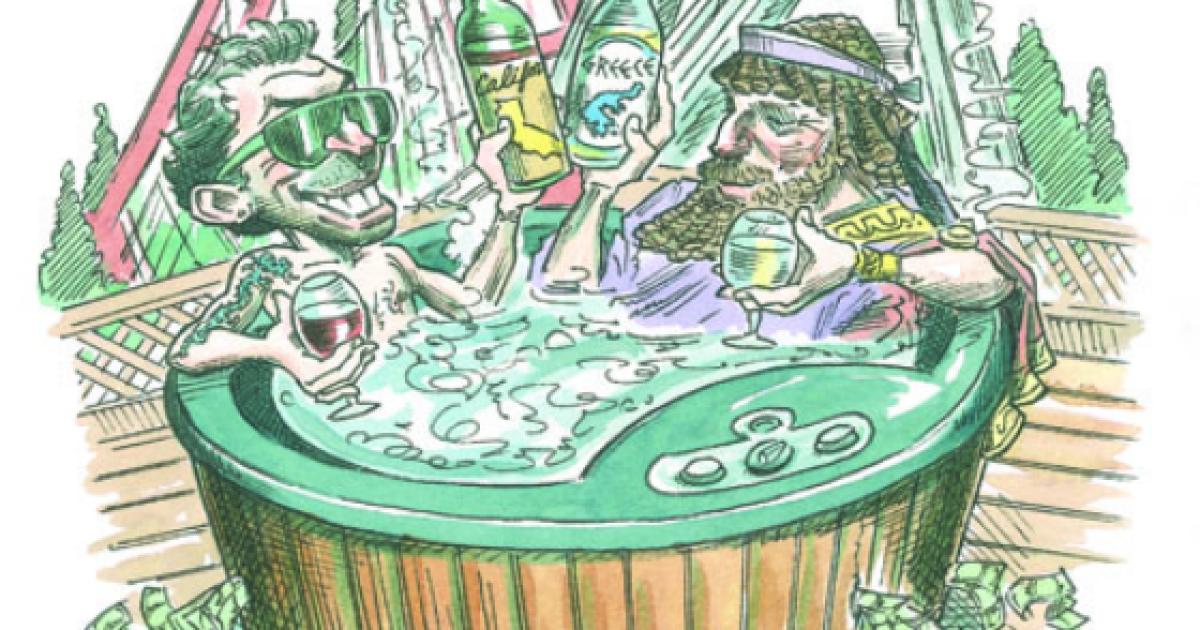

No one who has lived in Greece would be surprised to see national default looming. It’s a wonder that crazy things have lasted this long. The symptoms are well known: tax evasion is an art form and a matter of pride; pensions are absurd to the point of caricature; the public sector is self-righteous, bloated, and inefficient; and what little industry there is doesn’t meet European standards of efficiency and productivity.

Greece has a wonderful climate and rich soils, but few vast expanses of agricultural land, and farming there has so many built-in cultural and political impediments that vine, tree, grain, or cotton agricultural productivity lags far behind comparable farming in the United States, Australia, or Western Europe. All this unfolds amid a landscape of a naturally beautiful but otherwise largely resource-poor country, whose majestic, disparate terrain poses enormous problems for communications, transportation, and infrastructure. Tourism, EU membership, and the Olympics all brought scarce capital to the country, but not enough to match Greeks’ rising attitude of entitlement. The public readily spins all sorts of complicated and byzantine arguments why the standard of living in Greece must be roughly comparable to those of Germany or Scandinavia—or else.

Even more disturbing, the ongoing crisis takes place amid a regional landscape in which an ascendant (and fellow NATO ally) Turkey has decades-long disputes with Greece over Cyprus, territorial claims in the Aegean, and overflights of Greek airspace at precisely the time when budgetary implosions are forcing Greek defense cuts; the country is shrinking and its mountain villages are emptying; its allies in Europe are turned off by serial Greek recriminations; and four decades of cheap anti-Americanism has eroded almost all U.S. goodwill toward the country.

There is no way out except either sudden or gradual default, because a xenophobic Greek public assumes expansionary entitlements are an earned birthright and would treat any who would trim them as some sort of existential enemy. In that narrative, a greedy predatory northern European or American bondholder, wanting to pile up even more needless profits, enforces unfair and amoral terms on the courageous, brave, long-suffering Greek collective.

Once a society descends into that mindset, there is little alternative but the shock therapy of default, which, in the Greek case, would return it to something like the early 1970s, when I first visited: a nonconvertible, widely fluctuating drachma, a standard of living more akin to the southern Balkans or western Turkey than France or the Netherlands, a vibrant black market in money exchanges, tight controls on the possession of foreign currencies and a curtailment of imported goods, and very little new infrastructure construction or repair.

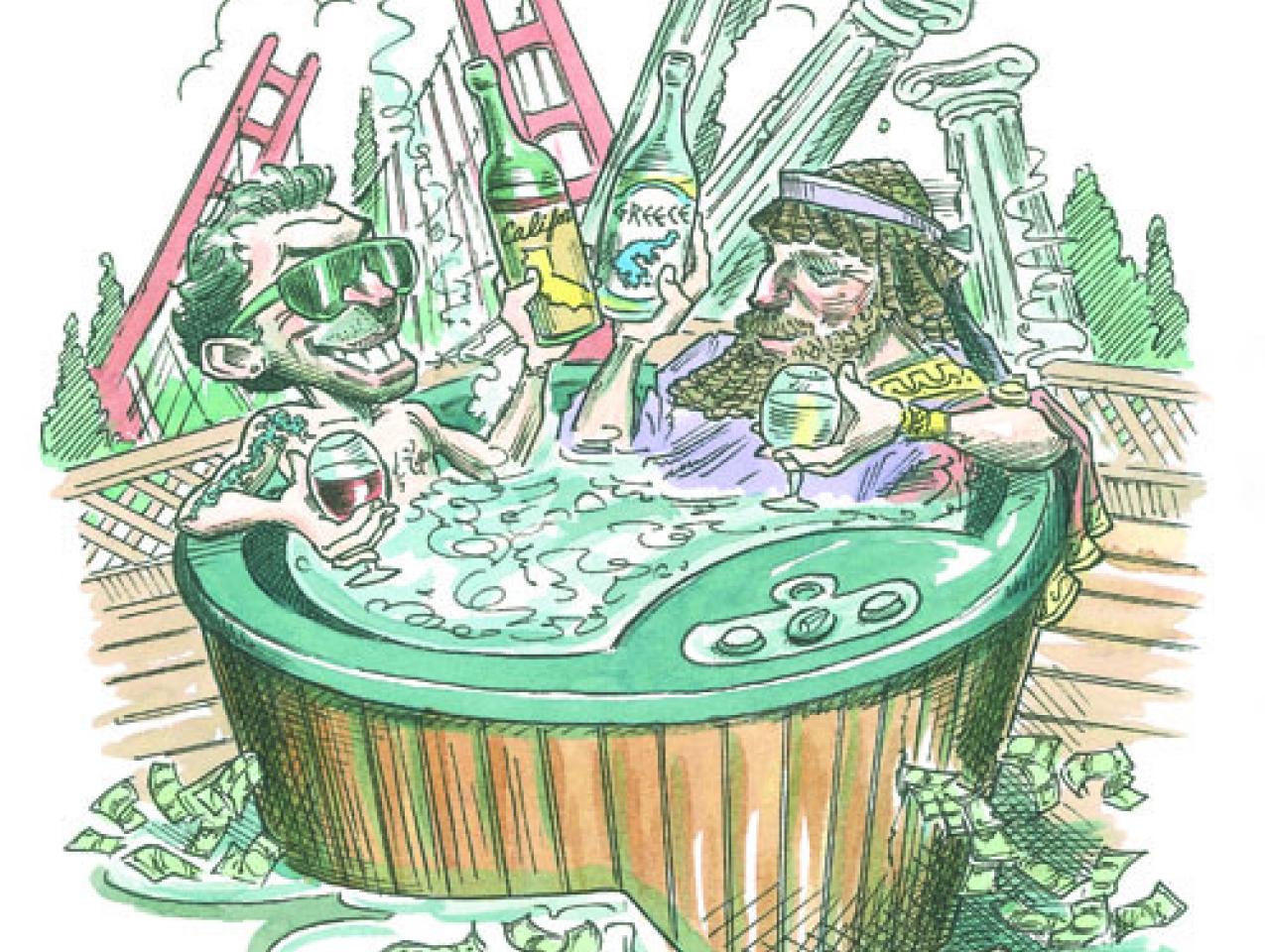

The Hellenic disease in its lesser forms is also spreading here in California, where entitlements have soared, illegal immigrants have vastly increased, and pensions and benefits of public employees have skyrocketed, while investments in infrastructure were largely neglected to fund redistributive payouts—all at a time when the affluent, income-tax-paying, and job-creating minority are leaving the state. The therapeutic California attitude is similar to that of the Greeks: even the slightest suggestion of cutbacks evokes class warfare and a litany of sanctimonious reasons why more, not less, public funding is critical for all sorts of victimized categories.

For now, Californians can enjoy the semblance of twenty-first-century living thanks to the state’s lingering advantages. These include the fumes of once-vibrant gas, oil, and timber industries; a highly productive agricultural sector that arose in the 1960s; the Napa Valley explosion of the 1980s; far-seeing investments during the 1950s and 1960s in infrastructure; Silicon Valley; and weather and geography conducive to tourism. These exist despite, rather than because of, state governance. That the state dreams of a multibillion-dollar high-speed railway even as its main north-south freeways collect congestion and potholes shows how hard it would be to save our state from this strain of the Hellenic disease.