- International Affairs

- Security & Defense

- Terrorism

- History

- World

The first week of January 2015’s biggest news—three Muslim jihadists murdering a dozen journalists in their Paris office, another killing four patrons in a nearby Kosher market, and the reactions to these events—leads us to ask what history may teach us about such people and how we may rid ourselves of them.

History has no precise parallel to the growing wave of murders throughout the planet perpetrated by persons who proclaim Allah and Muhammad. To be sure, history is full of instances of persons belonging to a group defined by blood or faith who murder members of other groups to assert some of their own group’s claims, and whose numbers grow by attracting some of their own group to themselves and intimidating the rest. But examining the differences between our present phenomenon and its partial antecedents—even more than the similarities—yields valuable insights.

History’s most touted campaign of assassinations, waged by a group that gave the practice its name, was by the Nizari Ismaili sect of Persian Shia against the Cairo-based Seljuk Sunni regime in the late eleventh century. But the Assassins, whose chief, Hassan-i Sabbah, was headquartered in the Alamut fortress, did not join spontaneously but rather were recruited and trained individually, and killed only the regime’s prominent enemies. Today’s terrorists are not Assassins.

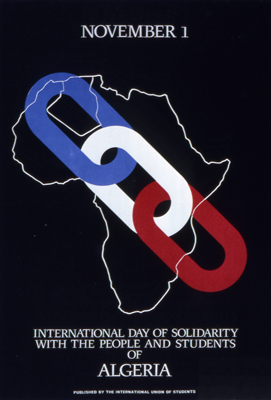

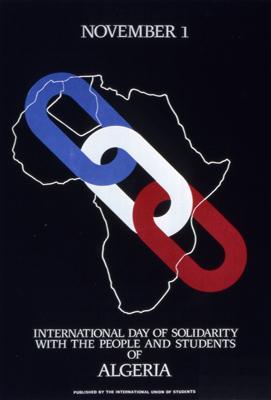

Today’s wave of jihad murders more closely recalls India’s Sepoy rebellion of 1857 insofar as it began as a single incident, but feeding on a complex set of resentments of British rule by Indians, spread spontaneously. More and more Indians who had no prior intention of doing such things took it upon themselves to inflict gross cruelties on the British among them. The Arab slaughters of Jews in the 1920s, which began on a small scale at the behest of the Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseini, and culminated in the 1929 Hebron massacre, differed from the former in that the role of longstanding, complex, underlying resentments was smaller, that of religion was greater, and that of organization much greater. The Mufti’s forces also intimidated or eliminated fellow Arabs who were unwilling to join the Jihad. Organization and intimidation of fellow Arabs was far more important in the 1954-1962 campaign by the FLN to drive Frenchmen from Algeria by murder, and religion less. By contrast, in the Muslim Brotherhood’s murderous 1990 campaign to drive the FLN from power in Algeria, organization played a much smaller role, religion and spontaneity a much greater one. Throughout history, countless instances of foreign occupation have been accompanied by more or less spontaneous revolts by scattered individuals, localities, and groups.

The closest example to contemporary jihadism of persons rising from quiescence, energized to murder, whose example spread like wildfire and endangered society, is from Europe’s late Middle Ages and Renaissance. Inspired by various prophetae who claimed to embody God’s cleansing wrath against corrupt religious and secular nobles, a baker’s dozen of movements known variously as “Anabaptists” or “Cathars,” led ordinary people to murder their neighbors. Part of their inspiration, like that of today’s jihadists, was the prophetae’s establishment of model states that they claimed embodied God’s promises and whose temporary success energized imitators.

All previous movements that share some of jihadism’s features, however, shared one feature the absence of which sets them far apart from twenty-first century jihadism. Whereas all such movements were trying to destroy societies and polities that pushed back very hard and crushed them by massive, brutal, and exemplary force, lack of resistance to its spread is the distinctive feature of today’s jihadism. Consider how different was the environment of all previous murder movements:

The Assassins really were tools of an institution that represented a well-defined sect, the headquarters of which was in one fortress. After the Mongol invasion wiped out Alamut in 1256, the sect ceased to exist. The Sepoy rebellion ended when British troops stormed the cities where the rebels had taken refuge, and repaid the rebels’ cruelties with interest by bayonetting and hanging whoever was at hand. Vigorous Jewish self-defense augmented British forces’ suppression of the Mufti’s pogroms. French forces stopped the FLN cold in 1956, efficiently targeting a meticulously designed campaign of counter-murder by applying torture intelligently. The FLN, for its part, crushed the Muslim Brotherhood with far less finesse and with brutality that was far more indiscriminate. The several medieval European chiliastic movements ended with slaughters on the battlefield, captives burned at the stake, etc. The leader of the last of these, one Jan Bockelson known as Jan van Leiden, was tortured in the main square of several cities before being placed in a cage and lifted to the top spire of Münster’s cathedral to be picked apart by the birds in the sight of all. The cage hangs there still.

By contrast, of all the countless activities undertaken, plans made, utterances formulated by Western authorities, none have been of the sort that aimed at or envisaged ending jihadism.

In America as elsewhere, “security officials” reacted to the Paris events as they have to all previous others, by promising to track down the perpetrators’ connections: to discover by whom they were recruited and trained, as well as to redouble efforts to keep track of persons who, like the perpetrators, have given reasons to suspect them of willingness to kill. At the same time, they voiced frustration at the fact that the burgeoning number of such people is making it impossible for them to do that, and that they have no means of restricting such persons’ access to the means of slaughter, whether gun or knife or moving car, arson, poison, or mob. Slowly, they are recognizing that, as jihadism spreads, connections and organization are less and less important, that jihadism has acquired a momentum of its own with which they are loath to grapple.

This sense of exasperation, that the phenomenon has escaped our ruling class’s intellectual and moral capacity to understand and defeat it, this contrast between jihadism, which is spreading unchecked, and the lack of plans or prospects for ending it, is causing European and American publics to lose what remains of their allegiances.

All too obviously, such words and deeds as are being deployed against jihadism stand no chance of getting in its way. Typically, Senator Lindsey Graham suggested that the only way to destroy today’s jihadists “is to have the people within the religion turn on them, have the capability to keep them at bay within the countries where they exist.” No one is holding his breath. Meanwhile, the jihadists intimidate more and more Muslims—and Western societies as well. Note that no major American media published the cartoons that triggered the Paris outrage, and all bent yet further to absolve Muslim authorities of any duty to crush the jihadists. Government officials, when questioned about what they are doing to protect their publics, talk about increasing universal surveillance—precisely what has not worked in the past—and say that safety will come in future years.

Meanwhile, whereas in past years only strict Muslims might have become jihadists, nowadays persons with scarce connection to Islam, or none, are joining it as a way of legitimizing their social or personal grievances. This is particularly important in America, where Islam and jihadism are spreading among those who are not of Middle Eastern descent, especially among African American male youth. Why or how radical Islam seems to be increasingly popular among particular minority groups is a topic that few wish to investigate.

In short, it seems that the jihadists, rather than as in the past making war on societies and groups intent on defending their lives, are now feeding off ones that flounder impotently as they suffer. They are less like assassins and more like jackals.