- Health Care

An important debate surfaced in the wake of Hurricane Katrina that could lead to a shift in social policy as significant as the welfare reform law of 1996. The devastation wrought by the hurricane in Louisiana, Mississippi, and parts of Alabama left many already poor people even more destitute. The nation’s sense of compassion was stirred, and thousands of volunteers and millions of charitable dollars flowed into affected areas. After initial missteps, the federal response intensified as President Bush and congressional leaders pledged significant resources to the region.

A great deal of the public and private aid is on hand and being utilized in the monumental rebuilding task. One benefit that has not materialized is the proposal by Senators Charles Grassley and Max Baucus to temporarily expand Medicaid health insurance coverage to all low-income persons affected by the hurricane. The debate over this legislation, its tepid reception, and the questions raised about how best to meet the health-care needs of the poor may have unexpectedly introduced the nation to its next major welfare reform target.

The Write-Up on Medicaid

Before considering the issue of Medicaid reform, understanding its purpose and reach could prove valuable. Medicaid is one of the three big entitlement programs in the United States, along with Medicare and Social Security. Medicaid often gets less attention from the media and in Washington than the other two programs, but it is actually growing at a faster rate and is now the largest and most costly government health-care program.

Medicaid was enacted as part of the Social Security Amendments of 1965 to assist states in providing adequate medical care to eligible needy persons. It started at the same time as its sister program, Medicare, which offers health insurance to the elderly. Medicaid was gradually phased in on a state-by-state basis between 1966 and 1972. Unlike Medicare, in which the federal government provides all the funding, Medicaid is jointly financed by the federal government and the states. In its first year, the combined expenditures totaled $1.7 billion, with the states paying just over half the costs. In 1972, with 49 of the 50 states on board, Medicaid spending had increased to $8.4 billion, covering a total enrollment of 17.6 million adults and children.

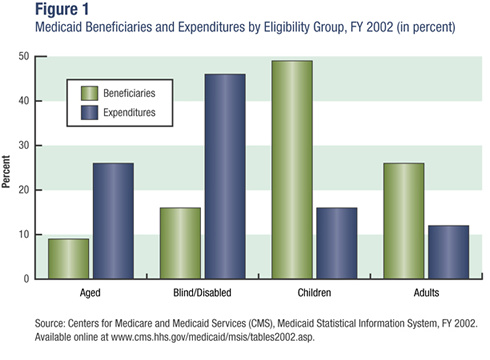

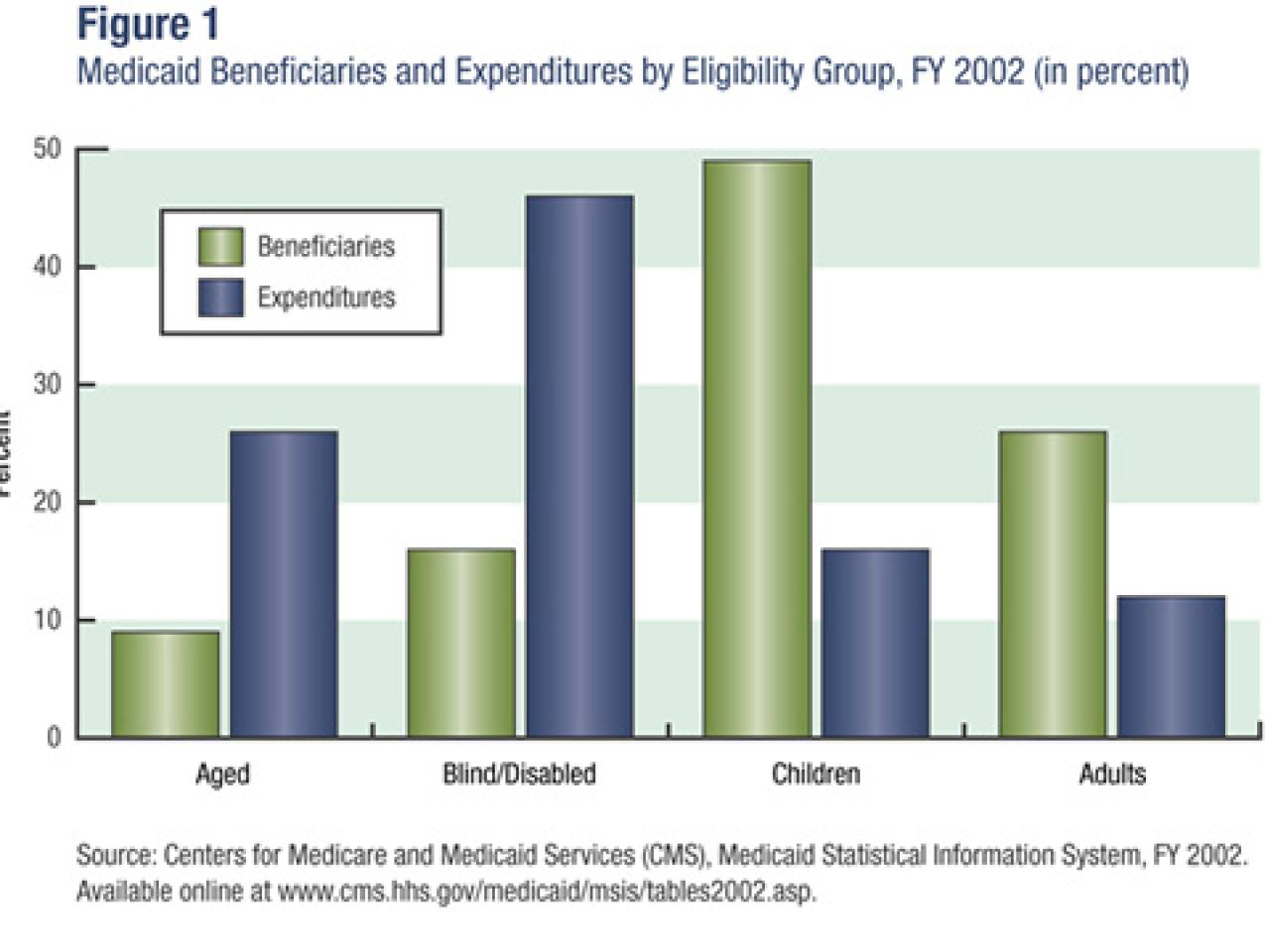

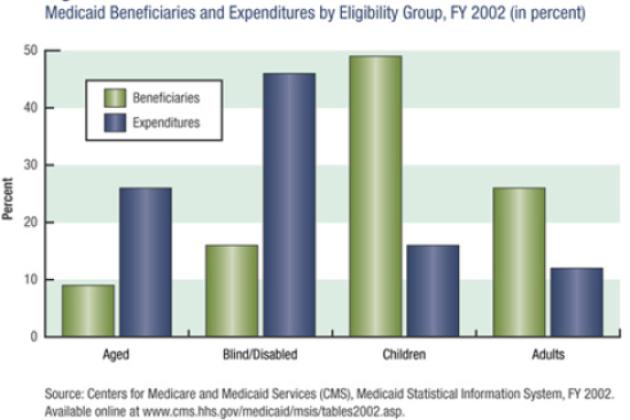

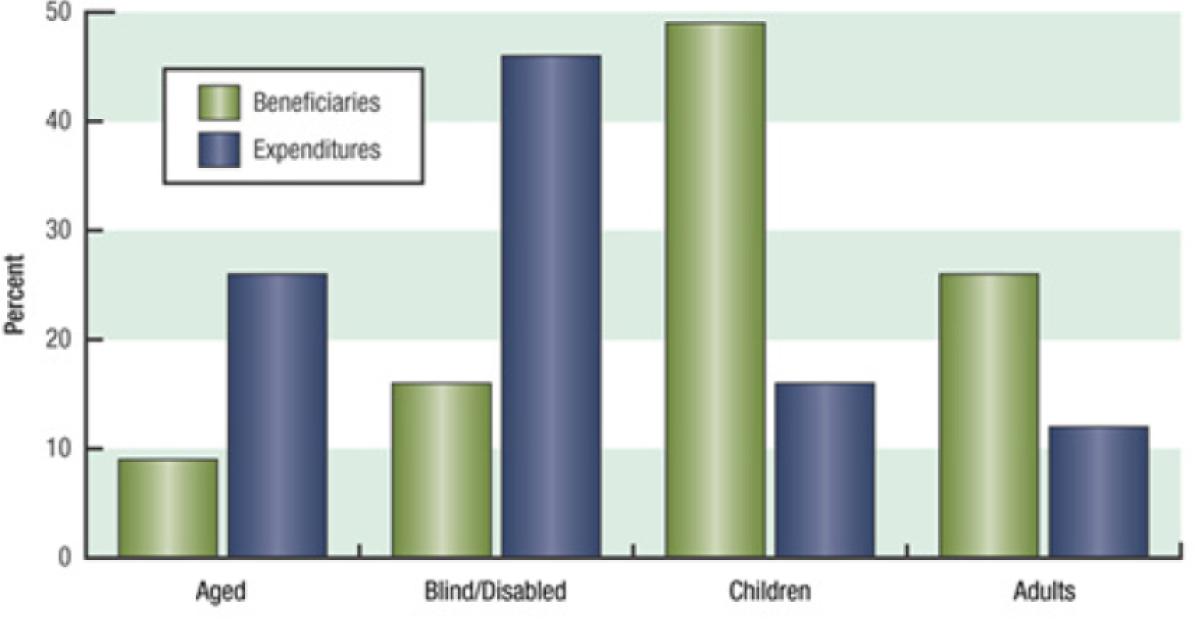

Medicaid serves a diverse population that includes foster-care children, mothers on welfare, and elderly nursing home residents. Although three-quarters of its beneficiaries are low-income women and children, together they only account for one-third of the spending on health care, meaning that the relatively smaller populations of aged and blind/disabled Medicaid recipients account for the lion’s share of medical expenses (see figure 1). This makes sense when one considers the high cost of personalized disability services and long-term nursing home care. According to a report by the National Bureau of Economic Research, “This panoply of functions has led to uneven program growth and some confusion about the mission of the program and how it integrates with other public insurance institutions.”

Adding to the confusion, each state is responsible for designing and administering its own program. Within federal guidelines, states determine eligibility requirements, program benefits, and reimbursements to health-care providers. The result is a patchwork of medical services and coverage that varies from state to state. Despite these differences, every state operates a Medicaid system that is characterized by price controls and a package of defined benefits. Together, these factors create inflexibility and fewer choices for beneficiaries.

A 40-Year Growth Spurt

Since its inception, Medicaid enrollments and spending have grown rapidly. That growth is in part a reflection of the rise in health-care costs nationally but is also a result of states’ loosening their eligibility requirements, resulting in more and more recipients.

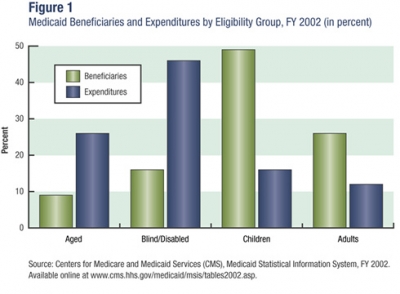

Comparing Medicaid to the next five largest federal “safety net” programs reveals just how disproportionate its growth has been (see figure 2 on page 110). Apart from the Earned Income Tax Credit, no other social welfare program has more participants. In 2002 there were more than 49 million Medicaid beneficiaries, or roughly 17 percent of the U.S. population, well above the national poverty rate. Although participation in cash assistance welfare (Aid to Families with Dependent Children or Temporary Assistance to Needy Families) has trailed off since the passage of welfare reform in 1996, Medicaid enrollment has continued to increase.

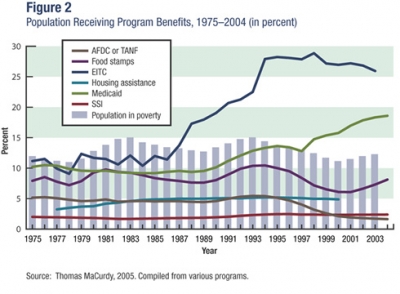

In terms of expenditures, Medicaid dwarfs the other major means-tested programs. Spending on Medicaid has risen steadily as a fraction of the federal budget during each of the past three decades, increasing from approximately 4 percent in 1975 to 13 percent in 2002 (see figure 3). That year, total outlays for the Medicaid program (federal and state) were $259 billion, or an average of $4,291 per recipient. And the costs are projected to continue to rise. “Medicaid—not Medicare—is now the largest government health program in the United States,” according to the programs’ administrator, Thomas Scully. “This trend is continuing,” he says, “with Medicaid outlays exceeding Medicare by about $4 billion in FY 2003 ($281 billion versus $277 billion), and estimated to exceed it by approximately $26 billion in FY 2004 ($304 billion versus $289 billion).”

Spending increases have contributed to the recent federal budget deficit. Earlier this year President Bush asked Congress to cut as much as $10 billion over five years from the federal portion of Medicaid’s budget. Of even greater concern is the impact rising costs are having on state budgets. Medicaid expenditures alone account for approximately 22 percent of all state spending, and more than half the states exceeded their Medicaid budgets in FY 2005. Many state constitutions require a balanced budget; thus the Medicaid cost overruns must be covered by either raising taxes or cutting spending in other areas such as education, law enforcement, or transportation. Without question, rising Medicaid costs pose the single greatest risk to state financing and solvency.

An Ailing System of Care

The fiscal crisis is the most obvious trauma threatening the Medicaid entitlement. But the immediacy of such concerns should not draw attention away from persistent quality-of-care and administrative problems. Public surveys confirm the commonsense conclusion that most Americans would rather have private health insurance than Medicaid. One reason is the dearth of doctors willing to treat Medicaid patients—according to one survey, 4 in 10 physicians have such restrictions. Additionally, cost-containment measures currently being implemented lead to rationing health care by means of restricted formularies and monthly limits on prescription drugs. Provider payments are being reduced, rules on eligibility and benefits are being tightened, and states are introducing co-pays to share costs. Each of these measures affects the quality and availability of care, producing a two-tiered health system that stigmatizes and harms the poor. Not surprisingly, dissatisfaction with Medicaid is common among recipients.

Administratively, Medicaid has endured years of mismanagement, abuse, and outright fraud. From health officials failing to secure prescription drug discounts to insurance scams designed to collect fees for phony treatments, problems abound. A major flaw in the design of Medicaid is the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP), or federal match, which has been shown in studies and congressional testimony to encourage “a variety of legal and regulatory loopholes to enhance the Federal funds [states] receive.” When the feds chip in two or three dollars for every dollar spent by the states on Medicaid services, the incentives to increase spending or expand the definition of “Medicaid services” are clear. The Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has recently taken steps to rein in such abuse and has made strengthening financial oversight a top priority. Although eliminating “gamesmanship” is important for government accountability, it will certainly exacerbate the trade-offs between state financial solvency and the quality/availability of care for Medicaid beneficiaries.

Right Diagnosis, Wrong Prescription

When Hurricane Katrina hit land on August 29, 2005, it exposed a lot more than the poor urban planning and antiquated levees of New Orleans. In President Bush’s words, “As all of us saw on television, there’s also some deep, persistent poverty in this region,” with “roots in a history of racial discrimination.”

Among the first tasks to confront was providing health care to the victims of Katrina. Within weeks of the disaster, two approaches began to take shape. On September 15, Senators Grassley and Baucus introduced a bill (S. 1716) titled the Emergency Health Care Relief Act of 2005. The $8.7 billion proposal principally alters Medicaid rules so as to provide relief to hurricane survivors and the affected states for an initial five months. The bill seeks to expand eligibility to women and children with incomes up to 200 percent of the federal poverty line, as well as childless men previously barred from Medicaid. Benefits are also enhanced, with generous coverage of treatments for emotional and psychological disorders resulting from Hurricane Katrina and extension of TANF benefits and unemployment compensation. Furthermore, S. 1716 absolves the states of paying for any of the Medicaid expenses incurred by eligible evacuees—eliminating the state match and reimbursing, from the federal treasury, 100 percent of the costs.

The second approach, championed by Health and Human Services Secretary Mike Leavitt on behalf of the Bush administration, involves granting waivers on a state-by-state basis. The waivers make it easier for states to meet the health-care needs of individuals enrolled in Medicare, Medicaid, and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program. Enrollees evacuated to other states will continue to be covered, and the standards for eligibility have been simplified to get health care to as many qualified evacuees as possible. In addition, cost-sharing and mandatory managed care will be suspended for evacuees and extra mental health benefits will be available. For individuals not covered through private or public health insurance programs, CMS will fund an “uncompensated care pool” to reimburse providers for services rendered to uninsured evacuees. One significant advantage is that Secretary Leavitt has the authority to grant waivers and has already reached agreements covering such waivers with Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas, among others.

Objections to the Grassley/Baucus approach include its high costs, entitlement expansion to childless adults, and delays in implementing planned reforms to FMAP. Criticisms of the Bush administration approach include some evacuees having been turned down for Medicaid, an inadequately funded uncompensated care pool, and Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama being unable to afford their portion of Medicaid expenditures, which are expected to be well above historical averages.

Whatever the shortcomings of the state waiver remedy, the risks involved in expanding Medicaid through legislation far outweigh them. Despite 40-plus years of massive government entitlement spending to eliminate poverty, Katrina revealed just how little progress has been made. Instead of breaking the cycle of poverty, entitlements such as Medicaid reinforce government dependency. Out-of-control costs, fraud, abuse, and poor quality of care point to a system on the brink of failure. The survivors of Hurricane Katrina deserve better. The short-term payoff of a $9 billion aid package is a bet our country cannot afford to make. Ultimately, the problems with Medicaid and the limitations of the federal waiver plan can only serve to heighten, as President Bush put it, our “duty to confront this poverty with bold action.”

New Treatments Offer Hope

If a new Medicaid entitlement is out of the question and federal waivers come up short, what “bold action” can we take? Following in the footsteps of welfare reform, Medicaid can be restructured to increase personal responsibility and enhance individual freedom. Our best option for securing and improving the physical welfare of impoverished Americans is to move away from a system of socialized health care. In its place, federal and state governments can use their financial resources to help the poor afford private medical insurance and services tailored to their specific needs.

Inevitably, detractors will argue that such a “scheme” is too risky and will hurt the poor while lining the pockets of wealthy private insurance corporations. The charges are always the same—vague and combative. But the facts say otherwise. A remarkable demonstration project is under way in several states called the Cash and Counseling Program. Under this program, certain disabled and older beneficiaries are able to purchase community-based care and home health services with cash allowances. They can shop around, hire and fire, and generally have their disability needs met on their time schedule and as they see fit. This dramatically alters the benefits structure of Medicaid in favor of the consumer’s interests. Benefits are no longer defined by bureaucrats but by those actually using the health services.

The results have pleased both the beneficiaries and the states, something Medicaid has failed to do on both counts. In Florida, an evaluation by Mathematica found that satisfaction among program participants is extremely high—99 percent were satisfied with their caregivers, 88 percent said that their quality of life had improved, and 97 percent would recommend the program. In addition to beneficiary satisfaction, the program has energized states by significantly reducing fraud and abuse and offering a way out of the annual growth in spending. The Cash and Counseling Program utilizes a defined contribution model that caps state expenditures. This prevents the program from going over budget and introduces incentives that encourage beneficiaries to spend wisely on their routine care. And there is a promise of additional fiscal savings for states as consumers opt for home care over more costly institutionalized care.

Cash and Counseling, although demonstrating the potential of consumer-directed health care, is designed for individuals with various types of disabilities and illnesses. For the vast majority of Medicaid recipients, a more simplified option is gaining traction. Premium support programs can take several forms, but all essentially give Medicaid beneficiaries the choice of receiving a financial contribution that can be used to purchase private health insurance. This approach is already being utilized in some states to help qualifying beneficiaries pay the premiums on their employer-sponsored health plans. But South Carolina’s proposal in June of this year to bring a consumer-directed, market-based environment to Medicaid takes this concept to a level never before seen. If bold action is required, this is a good place to start.

South Carolina has requested a waiver under Section 1115 of the Social Security Act to initiate a research and demonstration project. The goal is to foster the efficiencies of a consumer market by giving personal health accounts to most of the state’s 850,000 Medicaid beneficiaries. The accounts would be used by recipients to purchase health insurance or pay for medical care directly. As stated in the introduction, “We plan to create an environment where providers and insurers are freed from unnecessary bureaucratic requirements and can compete for the consumer’s dollar.” At the same time, Medicaid consumers gain an incentive to weigh the costs of their care and maximize the funds in their account. With a full array of market forces at work, there exists a real chance to both improve the quality and availability of care and significantly curtail spending growth. The changes proposed by South Carolina to its Medicaid program mirror some of the best and most innovative choices in the private health-care system today.

It’s too soon to know whether the federal government will grant such a far-reaching waiver. Still, the filing of the request marks a significant turning point in the effort to bring marketplace principles to the Medicaid program. The problems that plague Medicaid, including cost overruns, reduced benefits, and restrictions on eligibility, will not go away on their own. One critic of South Carolina’s proposal, state senator Kay Patterson, suggested that “the money should be there to take care of our people, those who cannot take care of themselves, regardless of what you have to do, whether it’s to raise the cigarette tax or some other means. . . . That’s the purpose of government.” Ideas have consequences, and those that have propped up the failing Medicaid system will continue be voiced. The question is, “Can we afford to listen any longer?”