- Contemporary

- World

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- History

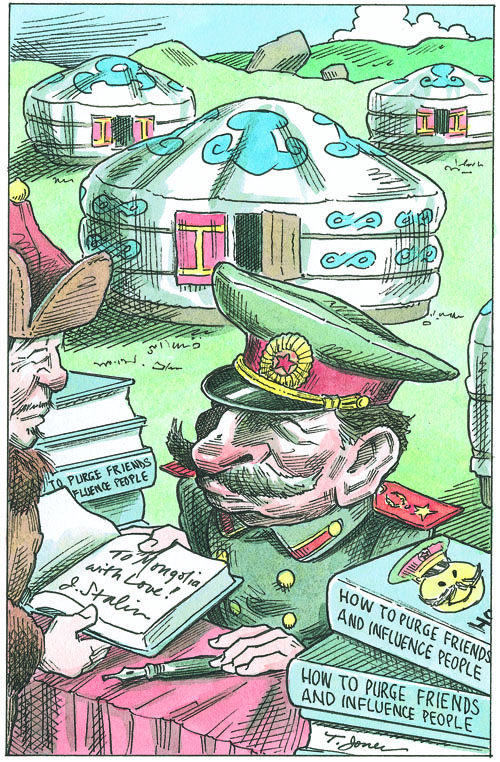

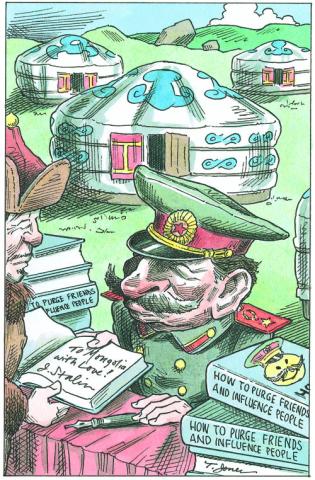

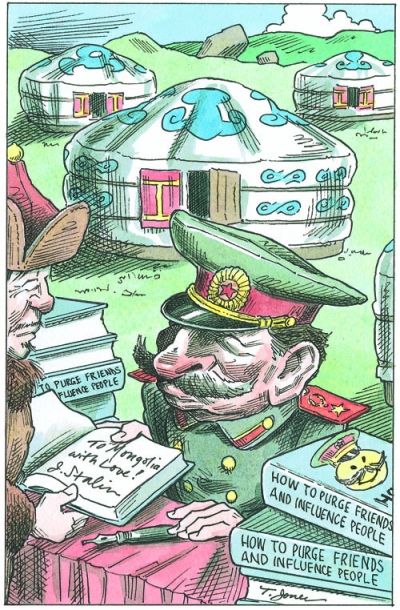

In the Hoover collection known as Fond 89 we find a document that can only be called a short course in despotism. The teacher: Josef Stalin. His pupils: the leaders of the Mongolian Communist Party, who had trekked to Moscow specifically for his tutelage. It was November 15, 1934, during a time when Mongolia had broken away from China and become a Soviet protectorate with a local communist government. The communists were opposed by Buddhist monks, who held sway over the nomadic population. Mongolia was important to the Soviet Union in light of the growing Japanese threat.

The Mongolian party secretary, Gendun, had brought along the delegation to collect their patron’s advice on how to defeat the monks. In the course of this conversation, Stalin imparted his wisdom on the first steps towards establishing a totalitarian regime. His playbook should be required reading for dictators the world over.

Stalin’s advice applied to a would-be dictator in a backward country facing significant resistance from a religious opposition. He warned his Mongolian visitors that they were not yet ready for the big time: forced collectivization, arrests, and outright terror. That could come later. For the time being, he counseled patience and emphasized the importance of winning the battle for hearts and minds.

A verbatim transcript of the three-hour meeting tells the story. The meeting begins in typical Stalin style, with the Soviet leader asking questions. He wants to know the facts about the Buddhist monks—“the greatest danger,” as he calls them, to the communist government: Are they well organized? Do they oppose you openly? Do the nomads believe them or the communists? In what language are religious services conducted? Do the monks finance their religious and educational activities with “voluntary or compulsory” contributions? Who controls and builds wells? Do you send party activists into monasteries to stir things up?

The Mongolian party leader’s answers do not particularly please Stalin. He is especially put out to hear that party activists cannot infiltrate evening prayers and that arrests of Buddhist leaders are met with strong protests.

After extracting a reluctant admission that the monks are more popular than the communists, Stalin, exasperated, concludes that Mongolia has “two governments” and that the Buddhists are the stronger. He then launches into a lengthy discourse full of advice, excerpts of which I provide here:

“In a war in which you cannot defeat the enemy by a frontal assault, you should use roundabout maneuvers. Your first action should be to put your own teachers in the schools to battle the monks for influence among the youth. Teachers and activists must be the direct conduits of your policy.”

“The government must build more water wells to show the people that they, not the monks, are more concerned about their economic needs.”

“In the case of the Buddhist leaders, it is necessary to charge them with espionage, not counterrevolution, so that the people understand that they are working for foreign enemies. But you can do this only from time to time at this point.”

“If you have workers who disagree with your policies, there is no need for roundabout measures. You must conduct against them the most merciless battle.”

“If the monks practice medicine, it is necessary to prepare your own physicians and veterinarians to counter their influence.”

“It is necessary to have a strong army in which not one recruit is illiterate. Along with other training, they must receive political training.”

“You should produce films and promote theater in the Mongolian language [to spread the communist message].”

“You should hold religious services not in Tibetan but in the Mongolian language.”

“As long as there is private and not state ownership, there will be exploitation of the poor by the rich. You must conduct a merciless battle against feudalism and monks by taxing them while providing support and subsidies to the poor and middle class.”

“You should not allow the rich in the party; only admit a few who are useful. You cannot give the party to the rich. You must hold power in your own hands.”

“Foreign powers will not recognize you as long as it is unclear who is stronger, you or the monks. After you strengthen your government and army and raise the economic and cultural level of your people, the imperialistic powers themselves will recognize you. If they do not, now being strong you can spit in their faces.”

“If you carry out all these measures, you will be stronger than the monks. They will stand before you on their hind legs.”

After the Mongolian party leader accepts Stalin’s advice “with joy,” the conversation takes an almost comical turn. The Mongolian leader asks: “And our independence?” Stalin assures him: “You have nothing to gain from independence from the USSR. The USSR does not want your land. We already have enough.”

The Mongolians then proceed to submit to Stalin proposed changes in the structure of government and their nominees for the most important positions in the party and state. They go over each name. Stalin knows about each one; he has done his homework. He then endorses the list of candidates, instructing that these nominations should be formally approved “back home.” So much for the independence of the Mongolian party.

EDITING HIS PLAYBOOK

Stalin obeyed his own advice to wait for a decisive move. In July 1937, almost three years after he met with the Mongolian party leaders, he sent the second in command of his secret police to Ulan Bator to personally supervise the purging of the Mongolian party elite. Stalin’s November 1934 conversation partner, Gendun, was among the first victims. A longtime survivor of intraparty struggles in his homeland and known for defying Stalin on occasion, Gendun was executed on a charge of conspiring with “lamaist reactionaries” and spying for the Japanese (remember Stalin’s counsel to accuse one’s enemies of espionage). When the purge was over, some 4 percent of Mongolia’s population had been killed, among them some twenty thousand Buddhist monks. Only one monastery was eventually reopened. (Today, Gendun’s former Ulan Bator home is the site of Mongolia’s Victims of Political Persecution Museum.)

The transcript is of interest in itself because it was extensively edited in Stalin’s own hand. Some of his edits are stylistic. Others clarify his comments relating to future collectivization. But a number of edits try to make him appear more statesmanlike. For example, he crossed out his remark about the USSR not needing Mongolian land and removed his reference to spitting on imperialists. Perhaps Stalin wanted a cleansed version of this document for his personal archive or a later publication.

Stalin’s playbook for the Mongolians shows why dictators and would-be dictators the world over have taken him as a model. We know, for example, that Saddam Hussein and Mao Zedong were apt students of Stalin. In this sort of challenge the Soviet leader was in his element. He had already practiced such an approach in Central Asia, where Muslim clerics, who enjoyed strong support among the population, opposed his policies.

In dispensing his advice, Stalin revealed patience combined with both flexibility and ideological rigidity. His long-run goal for Mongolia was totalitarian control by a communist elite loyal to him, but he counseled that the battle for hearts and minds must first be won in the schools and theaters and through the distribution of water. Arrests and repression were to begin slowly, leaving room for retreat if necessary. Enemies should be associated with detested foreign powers such as the Japanese. His rigidity is seen in his ultimate goal, the collectivization of a nomadic population—almost a contradiction in terms.

A MODERN POSTSCRIPT

China today faces a problem in Tibet similar to Stalin’s in the Mongolia of the 1930s. Tibet also has “two governments”—an official one subservient to Beijing and an unofficial one led by Tibetan monks, whose spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, fled in 1959 as Chinese forces suppressed the Tibetan uprising. China has made heavy investments in Tibet (as advised by Stalin) but has failed to win over hearts and minds. Tibetan monks have been suppressed in quiet campaigns; many have disappeared. Unable to find “loyal” Tibetans (as Stalin did in Mongolia), Beijing installed Han Chinese to run the official government. And Beijing also has followed Stalin’s advice to demonize the opposition as agents of hostile foreign powers. Among the many charges against the Dalai Lama is that he is an agent of the CIA.