- Campaigns & Elections

- Congress

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

How, then, given the historical pattern and the Democrats’ expectations, did the Republicans beat the odds? The answer is a combination of the advantages of incumbency, reapportionment and redistricting, President Bush’s popularity, and the Republican Party’s strategy for the 2002 elections.

Incumbency and Open Seats

In contemporary America, House incumbent candidates overwhelmingly win reelection, and 2002 was no exception: Only 4 incumbents of 378 running lost. This victory percentage reflected all the usual advantages of incumbency: money, name recognition, the frank (the free mailing privileges that members of Congress enjoy), constituent service, and pork-barrel politics.

Moreover, 2002 was a redistricting year, and across the nation districts were redrawn to ensure incumbents’ safety. In addition, Republicans gained from the reapportionment of House seats after the 2000 census, a result of the continuing population movement from Democratic-leaning Frost Belt areas to Republican-leaning Sun Belt areas. President Bush ran ahead of Al Gore in 228 House districts in 2000; he would have finished ahead in 238 of the post-reapportionment districts.

From 1988 through 2002, no single year shows less than 90 percent of incumbent members of the House winning reelection (even in 1994 when over 30 Democratic incumbents lost), and 2002 is the all-time high at 98.9 percent (see table 1). Given this level of incumbent safety, change in control of the House in 2002 would have to come from the 47 open seats (no incumbent running).

Because of their competitive nature, open seats draw the attention of both parties. These races usually have good candidates who are well funded. During the period of Republican House control (1994–2002), Republican candidates generally have done well in open seats, 1998 being the only year they failed to win a majority (47.1 percent) (see table 2). In 2002 the GOP won a whopping 66 percent of open seats.

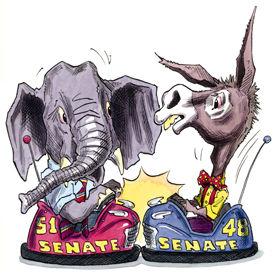

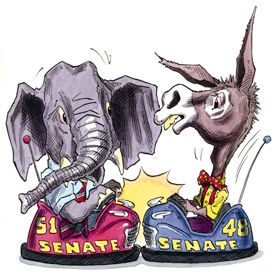

Senate elections in 2002 followed the House pattern. There were 34 seats up for election in 2002: 20 held by Republicans and 14 by Democrats. This greater Republican exposure (20 seats to 14) and the historical pattern of midterm loss led many to believe that the Democrats would gain seats. A closer look, however, shows that the Republicans were not as vulnerable as initially believed: 16 of the Republican seats were from states carried by President Bush in 2000.

There were 27 Senate incumbents running in the 2002 elections and 7 open seats (5 of which were Republican: North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and New Hampshire; and 2 Democratic: New Jersey and Minnesota). Only one of the Republican incumbents lost (Hutchinson of Arkansas), while two Democratic incumbents (Carnahan of Missouri and Cleland of Georgia) lost their reelection bids, giving the Republicans a one-seat gain. Among the open seats, there was just one reversal—the

Democrats lost Minnesota—giving the Republicans another one-seat gain. (The Republicans lost the December run-off in Louisiana.) Overall, 88 percent of incumbent senators were reelected.

The Broad Back of the President

Incumbency was clearly important in 2002, but it alone cannot explain the unusual Republican showing. The combination of Republican strategy and President Bush’s campaigning appears to have been crucial to the party’s electoral success.

The campaign strategy began with the party and the president recruiting strong candidates to run in seats where they had a chance: Coleman in Minnesota, Talent in Missouri, Thune in South Dakota, and Ganske in Iowa. During the campaign, the president focused attention on how he needed help in Washington, and the media focused on the potential war with Iraq. The Democrats could not make the sputtering economy or corporate scandals play with the American public. The final part of the Republican strategy was the old-fashioned but still effective notion of getting out the vote, especially in close states and districts. Preliminary figures show an increase in voter turnout of 4 percent from 1998 to 2002, suggesting that the GOP turnout effort was successful.

President Bush visited 40 states and more than 100 congressional districts. The president and his team carefully targeted competitive races. Open seats received special attention, as did seats held by vulnerable Democrats (observers believe that Bush visits to Georgia and Minnesota, for example, were critical to those Republican Senate wins). His appearances boosted local candidates not just by personal support but also by the campaign contributions he generated. Exit polls reported that 35 percent of those voting came to help the president, compared to 18 percent who came to oppose him. The president risked much by becoming so personally involved, but the results are impressive—he is the first Republican president in American history to increase his margins in both the House and Senate in a first midterm election.

Mandate?

What does the larger Republican margin in the House and the new majority in the Senate mean for public policy? As usual, the press has overstated the consequences. The Guardian wrote that the election would result in tax cuts for the rich, welfare cuts for the poor, the dismantling of key parts of the federal government, and the appointment of conservative judges. ABC News reported that Congress would privatize Social Security, pass a producer-friendly energy bill, and enact tort reform—among other things. John Dean, the former Nixon White House counsel, wrote a column predicting, “Bush is scouring the legal community for conservative judicial appointees. I promise you have seen nothing so far.”

The reality is likely to fall far short of such predictions. The “showtime” aspects of government will change a great deal—we will see more of Bill Frist and less of Tom Daschle on television, for example. The Senate agenda will take a sharp right turn as new Republican committee chairs conduct hearings and control the markup of legislation. Certainly changes in agenda control will have some policy consequences, but they are likely to fall far short of the consequences feared by liberals. Republicans probably will be able to enact a reasonable portion of the Bush tax plan; the president’s judicial nominees will now get out of committee, though not all will be confirmed; and there will be an energy bill. These initiatives and others, however, will be compromised by the fact that the switch from 49 to 51 Republicans does not alter two important facts.

The first is that moderate Republican senators such as Lincoln Chafee (Rhode Island), Arlen Specter (Pennsylvania), and John McCain (Arizona) will demand compromises both as matters of principle and as matters of political survival in their states. Second, and more important, Rule XXII in the Senate allows a minority of senators (41) to block action on most legislation. Thus, in order for most legislation to pass, Republicans will need a 60-vote majority, not a simple majority. In practice this means that the energy bill will not contain provisions to drill for oil in the Alaska National Wildlife Refuge and that controversial judicial nominees such as Charles Pickering will not be confirmed. President Bush’s public statements after the election reflected these realities as he urged Republicans to refrain from gloating (as Newt Gingrich and other party leaders did in 1994) and to keep legislative expectations to a reasonable level.

Finally, there is an old caveat that warns about the dangers of getting what you wish for. Republicans now have full control of the government after a midterm election for the first time since Calvin Coolidge in 1926, and the last Republican president to be reelected after controlling the government at midterm was William McKinley in 1900. Recent electoral history has shown us that presidents of both parties can use divided government to further their reelection by blaming failures on the opposition in Congress. In the post–World War II period, Eisenhower, Nixon, Reagan, and Clinton won reelection under conditions of divided government, but no president with full control has won reelection. In short, having full control of the government implies that the president and his party will be held fully responsible for their record and the condition of the country two years from now.