Foundations

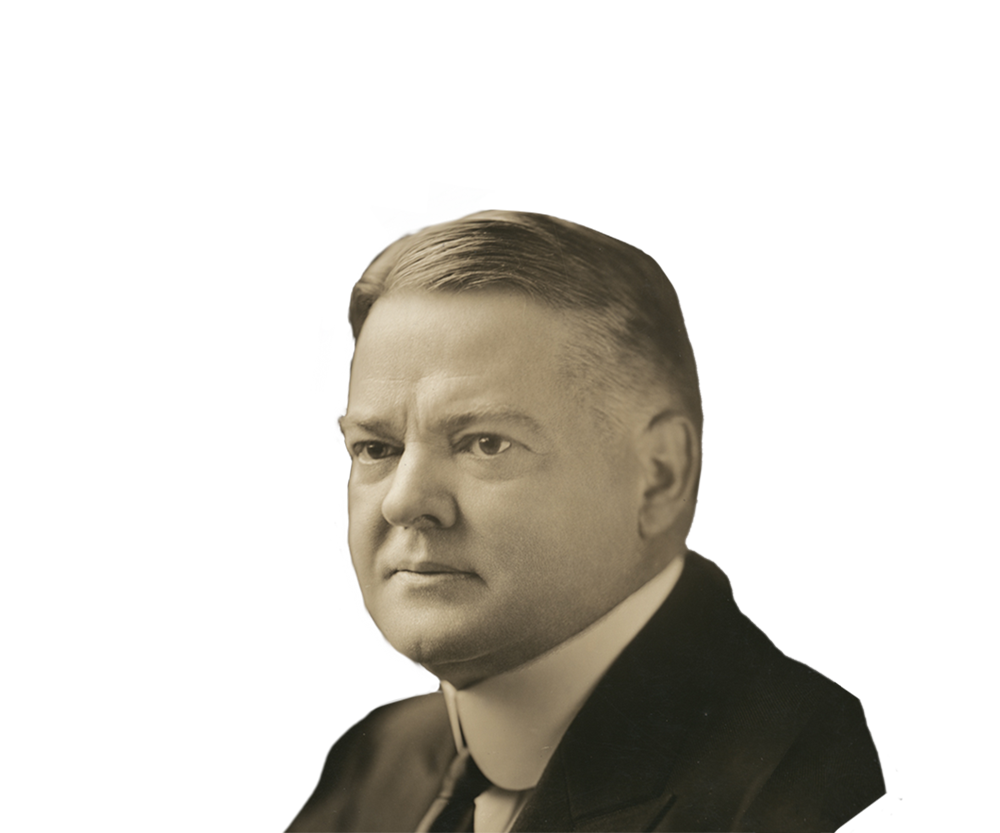

The Hoover Institution Library & Archives, with its vast original documentation on modern history, are a core component of the institution that Herbert Hoover (1874–1964) founded at his alma mater, Stanford University, in 1919. After graduating in 1895, Hoover built a successful career as an international mining engineer. While pursuing business interests, he found time to serve his university as a trustee. He maintained strong ties with faculty, including Professor Ephraim D. Adams (1865–1930) of the history department. Even before World War I, Hoover helped Adams acquire transcripts of documents from the British Public Records Office. Similarly, he supplied funds for another Stanford historian, Payson Treat (1879–1972), to purchase rare books on China and the Far East.

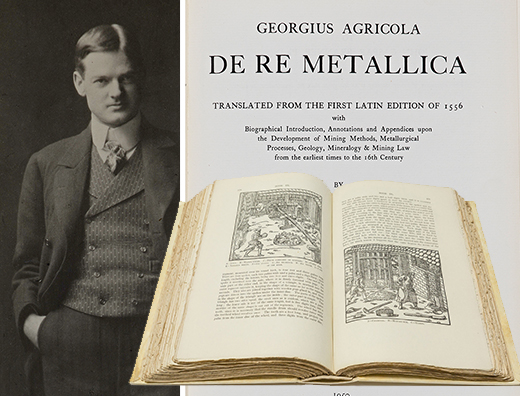

Hoover's lively intellectual curiosity motivated him to conduct research on the history of his own chosen field, geology. He delighted in writing scholarly footnotes to the English translation he and his wife made of the sixteenth-century Latin mining treatise by Agricola, De Re Metallica. By 1912 Hoover had become a confirmed bibliophile and an accomplished collector. At this time in his life, he was looking for a new arena where he could use his managerial skills to serve the broad public interest. These two disparate impulses—to collect scholarly research materials and to launch a new career of public service—soon converged.

An Idea Is Born

When the Great War broke out in Europe in 1914, Hoover became deeply involved in an unprecedented relief effort to help its civilian victims. He traveled freely through the war zones and negotiated with generals and heads of state. In 1915, his good friend Adams suggested that he save the records of his relief organization, the Commission for Relief in Belgium, and place them at the university for the benefit of Stanford students. The suggestion struck a responsive chord with Hoover, who was already aware of the need to document his organization for practical auditing purposes.

The idea was strengthened by the inspiration of another historian, Andrew D. White, whose remarkable career combined the two roles of building scholarly institutions and participating in high-level diplomacy. White had acquired a vast collection of ephemera from the French Revolution and placed these resources at Cornell University, where he served as founding president.

"I had collected in all parts of France, masses of books, manuscripts, public documents, and illustrated material on the whole struggle: full sets of the leading newspapers of the Revolutionary period, more than seven thousand pamphlets, reports, speeches, and other fugitive publications, with masses of paper money, caricatures, broadsides, and the like, thus forming my library on the Revolution, which has since been added to that of Cornell University." –see The Autobiography of Andrew D. White, New York: Century Company, 1905, vol. II, p. 489.

While crossing the English Channel to supervise relief efforts during the Great War, Hoover had read White's autobiography and had resolved on the spot to save the original records of the social revolutions that would no doubt be unleashed by the Great War. His goal was to provide the scholarly basis for understanding the international conflicts of the modern world. Hoover expressed the mission of the archives best:

Early Years

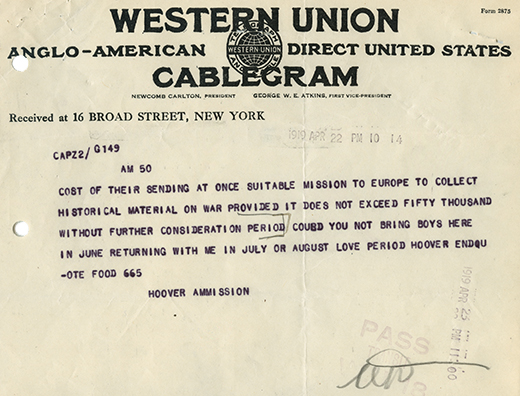

Hoover was ahead of his time in this collecting activity. The idea of preserving archival material was not yet well understood in the United States (the National Archives was not founded until 1934). In 1919, when Hoover offered the university a personal check for $50,000 to collect primary materials on the Great War, the president, Ray Lyman Wilbur, wired back for more explicit instructions. Once the purpose was clarified, Professor Adams went to Europe and began assembling materials for the Hoover War Library at Stanford. Adams collected pamphlets, society publications, government documents, newspapers, posters, proclamations, and other ephemeral materials because of their influence in stirring up nationalism and political movements. In his history of the origins of the archives, Adams emphasized that most of the materials were received as gifts and that reference books to support the archival collections were purchased with great care.

With Hoover's influence and at Adams's instigation, in 1919, General Pershing sent new orders to a talented Stanford history graduate named Ralph Haswell Lutz (1886–1968), who was with the US military mission in Berlin, to go to Paris to help build the collection; it became his life's work. Adams also recruited Harvard-trained historian Frank A. Golder (1877–1929), an expert on Russian archives, to collect both in Central Europe and in Soviet Russia.

Golder entered Soviet Russia in 1921 with a dual role. He served as an analyst and observer for the American Relief Administration, which supplied millions of Russians with food during the famine of the early 1920s. He also established contacts with the Soviet Ministry of Education, which enabled him to collect government documents and posters for the library. His contacts with the intelligentsia resulted in the acquisition of invaluable handwritten diaries and correspondence containing firsthand accounts of the Russian Revolution.

The founding collections of the Hoover Institution Archives include the extensive files of the Commission for Relief in Belgium, the US Food Administration, and the American Relief Administration in Europe and Russia. Hoover added materials such as nationalist pamphlets that he acquired in the course of his work for the Paris Peace Conference. These files, as well as the ephemeral leaflets, posters, and diaries that Adams, Golder, and Lutz collected, formed the basis of the institution. The emphasis was on saving materials that would ordinarily be quickly lost: publications intended to respond to a specific historical moment, eyewitness accounts of historical events, correspondence and memoranda by public figures, and files of international humanitarian organizations. Posters, film footage, and photographs were important components of the collection from the beginning. Most of the materials required special care and handling. Hoover was prescient in collecting source materials on ideologies such as fascism, communism, and nationalism, which he saw shaping the new global politics.

During the interwar period, Hoover's network of connections with major figures in the Russian emigration enabled him to rescue the official files of the Okhrana, the tsarist secret political police. These files, which were transferred from the Russian embassy in Paris, are a major source on the early years of such revolutionaries as Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin, as well as hundreds of grassroots organizers. Files from several tsarist consular offices were sent to the Hoover Institution for safekeeping by displaced diplomats, setting a precedent for saving the archives of defeated governments and dissident organizations so that all sides of the historical record are available to historians.

The papers of General Petr Vrangel' provide a unique understanding of the White Army during the Russian Civil War, whereas the papers assembled by Baroness Mariia Vrangel', the general's mother, chart the history of Russian émigré cultural life in various countries. These two aspects of Russian culture, which were eradicated in the Soviet Union, are preserved in the Hoover Institution Archives.

In a parallel example, Professor Lutz, who took a special interest in building the German collections, was able to document the 1918 revolutionary movement and the Weimar Republic even as national socialism was trying to destroy this page of the German heritage. Aware of the rising militarism in Germany, Lutz traveled to Europe in 1939 to make arrangements for collecting documents in the event of another major war. In Berlin he visited Mathilde Jacob, former assistant to the cofounder of the German Communist Party, Rosa Luxemburg. Jacob entrusted Lutz with original correspondence and notes of her former employer. A few years later, Mathilde Jacob perished in Theresienstadt.

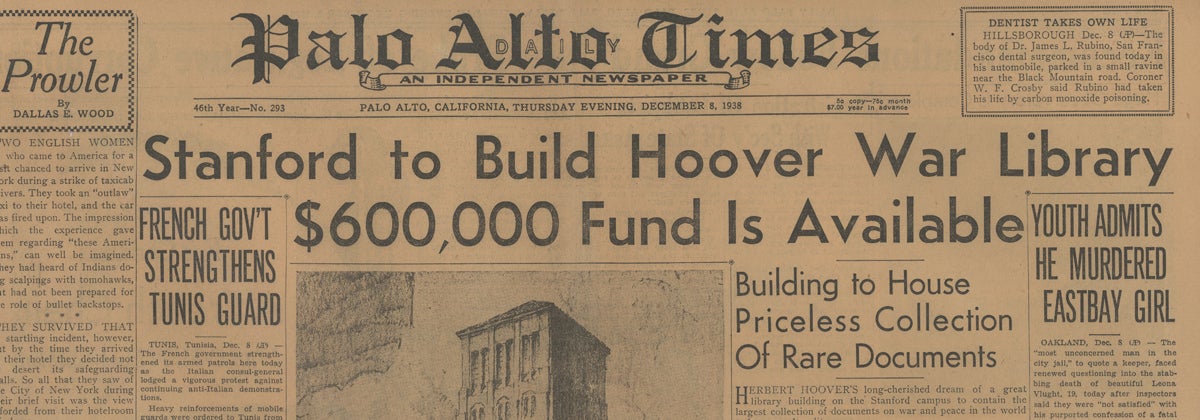

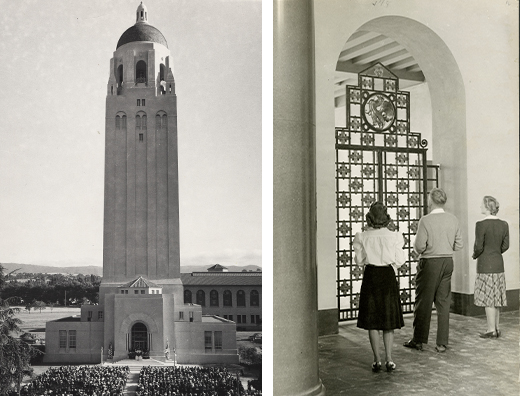

Hoover Tower

The archives, originally a repository for documentation on World War I, grew to encompass the records of the fascist, communist, and nationalist movements that precipitated World War II. When the university library no longer had space for the growing collections, Hoover raised funds for a separate building to house the library and archives. The Hoover Tower was designed by architect Arthur Brown Jr., who a few years before had built Coit tower in San Francisco. Completed in June 1941, the tower provided the necessary space to continue the work of documenting war, revolution, and peace.

The pattern of rescuing the history of persecuted political groups emerged again in World War II, when the archives came to the aid of the Polish government in exile and preserved files that would otherwise have been lost. Collecting efforts intensified in the wake of World War II.

The personal papers of General Joseph Stilwell and General Albert C. Wedemeyer provide unique insights into the China-Burma-India theater. The papers of Robert Murphy are a primary resource on the occupation and division of Germany. Materials on the early days of the United Nations can be found in the papers of C. Easton Rothwell, executive secretary of the founding conference of the United Nations and then director of the Hoover Institution.

East-West relations became a major theme in the collecting activities following World War II. The James Donovan collection documents a famous cold war incident when captured American U2 pilot Gary Powers was exchanged for Soviet spy Rudolf Abel. The Vietnam War is covered by collections such as the papers of General Edward Lansdale. Retrospective collecting continued with major acquisitions, including the Boris I. Nicolaevsky collection, the papers and art collection of tsarist diplomat Nikolai Bazili, and Russian literary manuscripts from Gleb Struve and Boris Pasternak. The Jay Lovestone papers document the founding of the American Communist Party and the international activities of the trade union movement.

Once the Hoover Presidential Library was established at his birthplace in West Branch, Iowa, Herbert Hoover's presidential papers and secretary of commerce files were transferred to the new facility. Further expansion room was still needed for the Hoover Institution Archives. The Lou Henry Hoover Building, added in 1967, housed the East Asian Collection until the early 2000s, when most of that collection was transferred to Stanford University. The archives holdings were moved from the Hoover Tower into a third building, the Herbert Hoover Memorial Building, in 1978.

Postwar financial reconstruction is reflected in the papers of economists such as Friedrich von Hayek, Milton Friedman, and other members of the Mont Pèlerin Society. Theories of freedom are articulated in the papers of the British philosopher of Austrian background Sir Karl Popper and the American philosopher Sidney Hook. Other major areas of interest include the history of the nuclear age, with the papers of various members of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, including Dixy Lee Ray. Education policy became another major collecting interest, with the collections assembled by Paul and Jean Hanna. Active collecting of election campaign materials shows the workings of democracy in various parts of the world such as postapartheid Africa and postcommunist Eastern Europe and Russia. The Hoover Institution Archives has continued its tradition of saving the history of political victims by securing the records of such organizations as the International Rescue Committee. At another level, its effort to microfilm the Archives of the Soviet Communist Party and the Soviet State in Moscow yielded eleven thousand reels of official Soviet documents, many of which are not easily available to researchers in Russia.

Major American political figures who contributed collections include extensive papers from members of Congress such as Paul N. McCloskey and S. I. Hayakawa. The papers of George P. Shultz provide a panorama of high-level policymaking and diplomacy.

Present Day

In all there are more than six thousand separate collections in the Hoover Institution Archives, including millions of individual documents from the entire range of twentieth-century history and politics around the world. Detailed descriptions of the histories and major collections of each curatorial area are available for Africa, the Americas, East Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and Russia/Commonwealth of Independent States. Some of the most heavily used collections are the subject files on specific countries as compiled by the area curators. The poster collection is also extensively used and supplies images for documentaries, book jackets, and a growing body of work on political iconography. All this material is stored in more than 100,000 boxes and made available for use in the Hoover Institution Archives reading room.

The political themes identified by the pioneering collectors in 1919 proved to be of immense importance to scholars throughout the twentieth century. It is no longer possible to track all of the articles, books, and films that have used materials from the Hoover Institution Archives. Some have become classics, such as Barbara Tuchman's Stilwell and the American Experience in China and William Shirer's Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Recent examples of well-received books that mine the institution's resources include The Russians in Germany by Norman Naimark and Germany Unified and Europe Transformed by Philip Zelikow and Condoleezza Rice. Countless television documentaries in the past twenty years have utilized film footage of the Russian Revolution from the Herman Axelbank collection. A large number of Stanford University classes attend research workshops sponsored by the archives to understand the methodology of original archival research.

Current collecting efforts are in place to anticipate new research trends in areas of dramatic social change. The rubrics outlined by Herbert Hoover, "war, revolution, and peace," have proved to be central to the modern experience. Although areas of collecting necessarily shift, the purpose of the records in the Hoover Institution Archives remains the same: "to promote peace."