As one of the world’s largest repositories of archival materials generated by diplomatic, military, and government officials and institutions, Hoover Archives contains an enormous amount of formerly top-secret documents: the plans for the D-Day invasion of Normandy, as well as files on Adolf Hitler’s personal traits and habits (strict vegetarianism; trips to the dentist to remedy a mouth full of cavities resulting from obsessive cake-eating; post-assassination attempt hypochondria), and counterterrorism files from the Reagan era. Since 2001, a US government team has periodically visited the archives to review security-classified records, which are then evaluated by relevant federal agencies. Some records are released in full, others in part, and some remain classified.

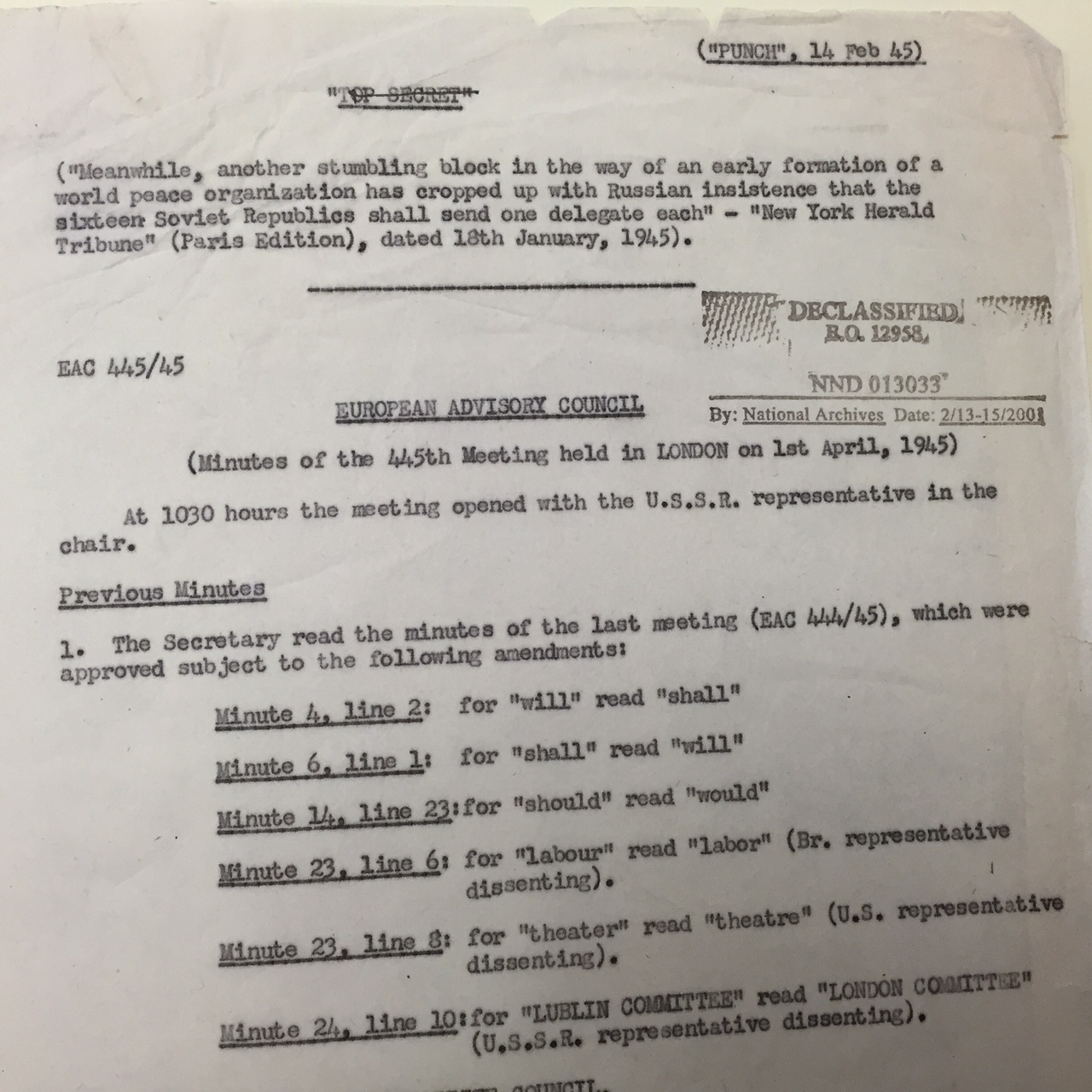

Following the declassification team’s most recent visit to the archives, Hoover archivist Sarah Patton has reviewed collections for which materials have been cleared. Among the many finds that will be featured in a new series of articles on declassified materials was a document from the John Marshall Raymond papers dated April 1, 1945, and titled “Top Secret”. Upon close inspection, Patton discovered that the declassified document was indeed not a smoking gun but an April Fools’ joke more than seventy years old: a spoof of the post-World War II era that is as instructive to historical study today as it was to current events then. Patton also discovered that the document in question (a parody of minutes kept in an Allied Council meeting) was not actually official but was, in fact, a draft of an article that ran in the February 14, 1945, edition of Punch, the well-known British humor magazine. The discovery of the document calls into question whether or not John Marshall Raymond, a colonel in the US Army, was the author of the parody, which is signed by a trio of “joint secretaries” that we can only assume must be false or fictitious: the US secretary is a “Major Omar V. Stuntz.”

Why—and how—did this April Fools’ antic end up in John Marshall Raymond’s archive? Raymond, a colonel in the US Army, served during 1948-49 as the director of the legal division of what was then known as OMGUS. Before the acronym OMGUS took on its current, antagonistic —and hardly fit to print!— meaning in the Twitterverse, the abbreviation stood for an organization that was, ostensibly at least, aimed at creating a sense of harmony that was a far cry from the more modern iteration. OMGUS, in the years following World War II, stood for the “Office of Military Government, United States,” a military organization formed to maintain peace in occupied areas of Germany after the country’s surrender to the Allies, to demystify Nazi ideology among German citizens, and to locate and return art and cultural artifacts that had been looted by the Nazis. OMGUS was part of an Allied Control Council made up of military and government leaders from the United States, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union.

The document, therefore, is a parody written to emphasize that negotiations among the World War II victors was strained at best, with each of the Big Three seeking to assert its dominance and progress stymied in a morass of legalese and bureaucratic wrangling. Within the mock-minutes, the British and American delegates argue over spelling and diction (labour or labor? theatre or theater?), while the USSR demands that all sixteen states of the Soviet Republic be given a representative. When the United States counters that it would then demand forty-eight representatives for each of its states, the British committee interrupts to report that according to the records of its Foreign Office, the United States should only consist of thirteen states. Further spoofing British colonial spirit, the minutes record that, after a brief adjournment for tea, the British reported that according to their calculations, the commonwealth as a whole would grant them forty-nine representatives, allowing them to outrank the United States. The political wrangling is finally broken up by a commotion in the hallway: “on inquiry it was discovered that a foreigner calling himself ‘de Gaulle’ had attempted to get in but had been overpowered and removed to safe custody.”

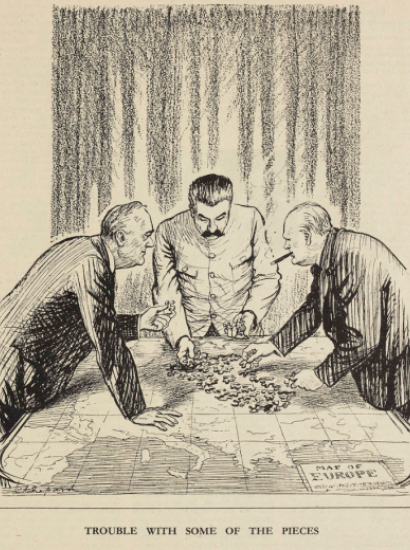

Although we may never know if John Marshall Raymond penned those quips, it is significant that he chose to keep a transcription of the parody in his papers among other documents that were indeed top-secret, containing sensitive information that would influence the developing Cold War politics outlined in the April Fools’ Day satire. The 1945 edition of Punch that included the “Top Secret” spoof of Allied negotiations also included a cartoon entitled “Trouble with Some of the Pieces,” in which Joseph Stalin, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill bend over an unfinished jigsaw puzzle of the map of Europe. Published just one year before Churchill’s Iron Curtain speech and two years before Stalin responded to the Marshall Plan with the Zhdanov Doctrine, the illustration and the “Top Secret” article testify to a crucial moment in history when the continuous rivalries of the victorious Allies began to shape the remains of the twentieth century.