By Kera Lovell

As a PhD Candidate in American Studies at Purdue University, I traveled to the Hoover Institution as a Silas Palmer Fellow in June of 2016 to conduct research for my dissertation and first book project titled, “Radical Manifest Destiny: Urban Green Space and the Battle for American Identity.” My dissertation examines the urban realm as a contested territory for American identity in the late-twentieth century. Urban studies scholars have illuminated how cities became the context of contentions over power and space in the post-World War II era, yet nestled within scholarship on utopian communalism, political organizing, and urban planning lies the undocumented history of radical community-based design as a form of public protest. My dissertation traces a transnational movement of activist coalitions that illegally occupied, created, or reclaimed green space. Utilizing a range of archival collections, oral histories, and spatial analysis, I argue that as practices of experimental community-based urban design, insurgent place-making initiatives—such as the takeover of vacant lots and creation of guerrilla gardens and parks—facilitated coalitions that transcended ethnic, racial, and national borders in an effort to redefine American identity. Ultimately, these protests and parks ignited global conversations that linger, raising questions about space as both property and a representation of power.

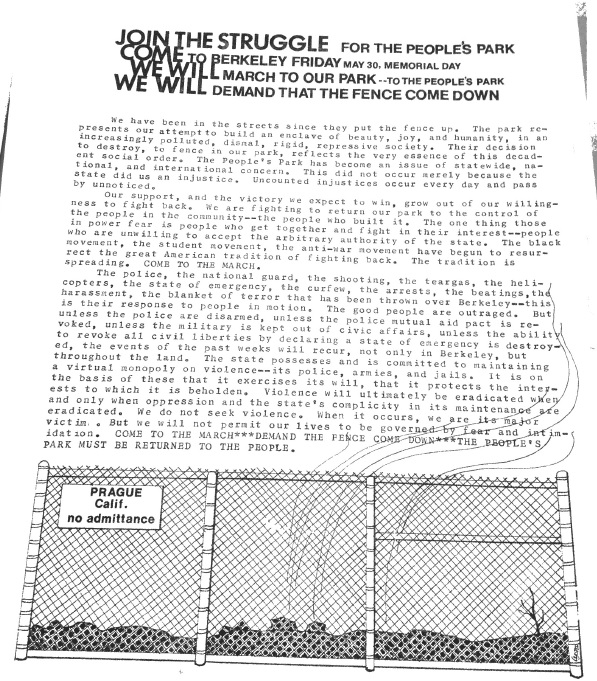

Beginning with protests at Columbia University and UC Berkeley in 1968, my dissertation focuses on the People’s Park movement that was sparked by the creation of an activist-created recreation area on a vacant lot in Berkeley in 1969. The 2.8-acre site, purchased by the University of California in 1967, was a muddy lot that had once been the home of cheap student housing prior to demolition—part of an expansive post-war urban renewal plan that included “rehabilitating” the increasingly hippie neighborhood between Haste and Dwight. A group of young liberals published a call in the local underground paper for those interested in independently converting the lot into a park show up with shovels in hand. Over the course of a few weeks, volunteers and fans of the community-created park grew to more than a thousand. In that short time span, the lot was stripped of debris, organized into brick-lined pathways into thematic stations, from vegetable gardens and an amphitheater to a children’s playground and barbecue pit. The majority of People’s Park’s history has been recounted through the telling of its aftermath – months of at-times violent altercations between park advocates and their adversaries who ultimately “paved paradise and put up a parking lot” (Mitchell, Big Yellow Taxi).

Although Berkeley’s People’s Park has been considered by many scholars as a singular site of insurrection, my dissertation situates its formation and popularity within a momentum of community-based design in which both radicals and planning and architectural practitioners worked together to reclaim power in the urban realm. My work documents a transnational movement of protests for access to and power over the design of urban green space from the late-1960s through the late-1980s. Having identified more than forty activist-created “people’s parks” between Berkeley and Johannesburg, my project analyzes the design, marketing, and memories of these parks as a lens into the politics of territoriality. People’s Parks became blank canvases for different political, cultural, and environmental agendas of their diverse makers, yet despite these differences, each newly-created park was imagined as a liberated zone in which top-down regulations of urban planning were supplanted by a socialist ideology of participatory urban design. People’s Parks became homes to a variety of programming, including squatters’ camps, rock concerts, political rallies, community gardens, and shared feasts where park goers could embody overlapping identities by “playing Indian” (Deloria, 1999) and exoticizing “the Other” (Said, 1979). Yet these spaces also facilitated cross-cultural coalitions in ways that transformed the urban realm into political, ethnic, and national borderlands—“la frontera” (Anzaldúa, 1987).

In search of racial, national, and gendered discourses embedded within urban green space in the 1970s, I began my research fellowship at the Hoover Institution by tackling several collections of local professors that contain largely unexcavated material on Berkeley’s People’s Park, including the Hardin B. Jones Papers and the Kenneth G. Fuller Collection. The greatest shared strength of these collectors was their amassing of editorials, mainstream newspaper coverage, and underground journal articles on Berkeley’s People’s Park from the Berkeley Daily Gazette, San Francisco Examiner, The Stanford Daily, The Daily Californian, the Oakland Tribune, as well as leaflets, posters, and underground press coverage. These opinion pieces and photographs largely concentrated on the violent aftermath of the park’s creation, from May 15, known as Bloody Thursday when local deputies shot dozens and killed an unarmed bystander, which has been used by both park advocates and adversaries to prove unnecessary violence as spatial infringements on the rights of American citizens.

Next, I tackled the papers of civil servants, politicians, and advisors to then-Governor Ronald Reagan, including Don Mulford and Edward Meese, in an effort to understand the extent with which local government and the state reinforced negative perceptions of the park as a site of anti-Americanism. Examining their personal letters, memos on law enforcement, and copies of Reagan’s speeches offered much insight into how the state used property law to argue that the park infringed upon the university’s right to own and develop land as a right of American citizenship. In addition, I was able to hear speeches in 1979 reflecting back on the People’s Park riot in the Ronald Reagan Radio Commentary Recordings collection, that evidence how the issues of power in public space remained a subject of contention a decade after the creation of People’s Park.

Finally, two expansive collections that proved helpful were the New Left Collection and the South African Subject Collection. While the New Left Collection contained extensive materials on People’s Park, broader Berkeley-area activism, and racial power movements, the South African Subject collection was of particular significance because it housed non-digitized primary sources on Johannesburg-area People’s Parks as well as anti-apartheid actions like UC Berkeley’s and Stanford’s shantytowns. The diversity of materials and subjects in these extensive collections made them the most rewarding excavations of my trip. Additionally, these collections helped whet my appetite for my next project analyzing race, gender, and the body politics of performance in Vietnam War-era food justice organizing.

Taken together, linking the methodologies and ideologies of People’s Parks across national, racial, and historic borders reveals a transnational movement of community-based design as a coalitional method of spatial and environmental protest. With the help of archival research at the Hoover Institution, my investigation into the visual, material, and spatial culture of these parks will ultimately illuminate how group, activist, and national identities are constructed within the territories they occupy and the meanings and myths they bring to that occupation.