This exhibition of government posters, photographs, fine art, and rare editions of poetry has been gathered from the collections of the Hoover Institution Library and Archives, the Cantor Center for Visual Arts, and the Special Collections of Stanford University Libraries. Members of Professor Peter Stansky’s class, Art and History: Modern Britain, were the guest curators.

This exhibition features two versions of British participation in the First World War (1914–18): one by the British government in thousands of posters and one in nonofficial war art, poetry, and photographs.

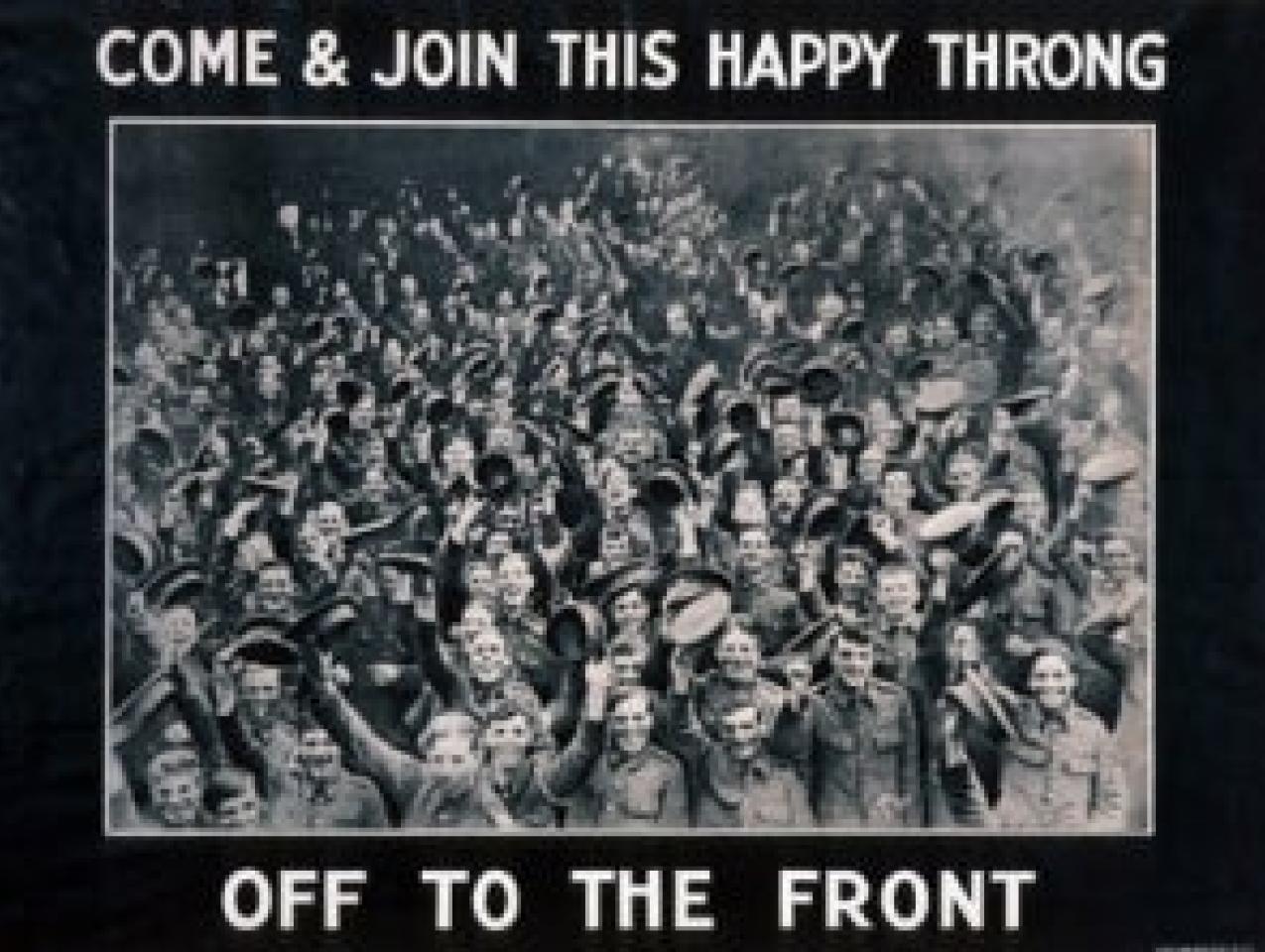

Because Britain did not introduce conscription until 1916, the country needed volunteers. Urged on by images and texts that promoted duty, the protection of women and children, manliness, and patriotism, more than two million men enlisted. Once the volunteers had spent time in the trenches, however, the war, with its anonymous death by fire power and clouds of poisonous gas, had become for them a “dance of death.”

Members of the class History and the Arts: Modern Britain, taught by Stanford history professor Peter Stansky, provided the text and chose the images for the exhibition. We would like to extend a special thank-you to the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University for the loan of the Percy John Smith Dance of Deathetchings and to Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries, for the loan of poetry texts. All other materials are from the collections of the Hoover Institution Library and Archives.

"Come & Join this Happy Throng Off to the Front" -- UK 481, poster collection, Hoover Institution Library and Archives

Below are brief descriptions of the themes in the exhibition cases. (The slide show contains at least one image from each case.) Descriptions of each theme, written by students in Professor Stansky’s class, can be viewed at the exhibition or by clicking on the title of each case.

Creating an Army

To counteract the large numbers of men conscripted by the German government, English officials had to enact an aggressive propaganda campaign. The vast output of the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee’s posters, leaflets, and newsletters, appealing to patriotism, honor, and manliness, among other virtues, resulted in a volunteer force between 2 and 3 million.

Enlisting the Irish

Recruiting for the Great War drew in a quarter of a million Irish soldiers, but was the campaign as successful as it might have been? Certainly it was successful in the north, but it may be that the recruitment efforts of the British in the Great War gave Ireland a large, trained force of soldiers who then used their skills in the fighting in Ireland that followed the war.

Mobilizing the Women

Britain mobilized not only men but also women to contribute to British victory. Propaganda posters merged women’s domestic duties with national duty, transforming domestic femininity into a form of patriotic service.

Demonizing the Enemy

Although British appeals to nationalism and the glory of empire certainly did their part, the First World War could not have been won without a certain amount of fearmongering. Despite the ruling royal family of Britain being German in origin and Germany’s having been a British ally in earlier wars, notably against Napoleon, the enemy had to be portrayed as less than human.

Helping the Old Lion

Britain, the “old lion,” the greatest imperial power at the turn of the twentieth century, was greatly assisted by its dominions and colonies in its battle against the Central Powers in the First World War. At the outset of war, in August 1914, Britain’s self-governing dominions of Canada, Newfoundland, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa joined the war effort against Germany.

Paying for the War

The British government spent as much during the years between 1914 and 1920 (£11,268,000,000) as it had during its prior 226 years, 1688–1914 (£10,944,000,000, not adjusted for inflation). By 1920, the British war debt was £8,079 million.

Illustrating a Modern War

The use of art as propaganda was overseen by Wellington House, a War Propaganda Bureau established in August 1914 to spread the British government’s view of the war to neutral and later allied countries, especially the United States.

Returning Home

The three posters in this case make clear several aspects of postwar British society, including discontent, both real and manufactured, over how the government had handled the war and its aftermath. At the same time, the public greatly respected its soldiers, making them a primary symbol for those seeking to sway public opinion.

Read an article about the exhibit, published in Hoover Digest.