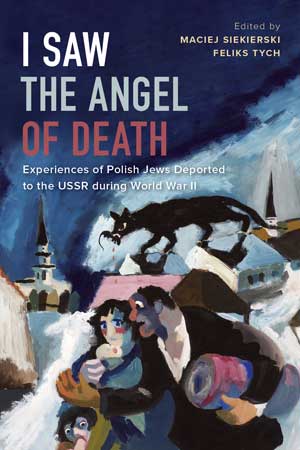

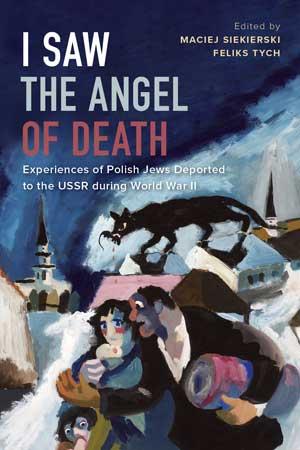

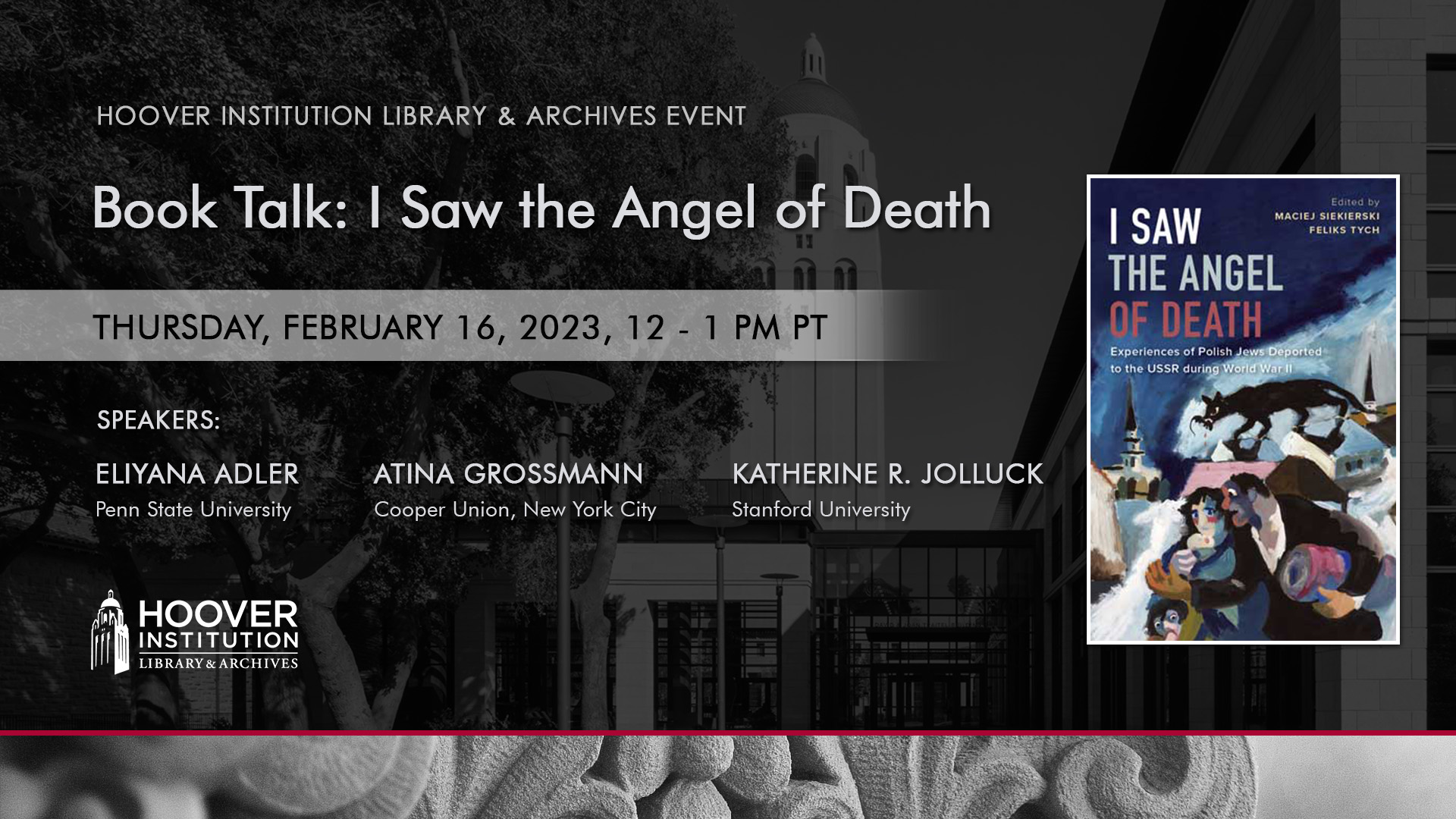

The Hoover Institution Library & Archives invites you to a book talk on Thursday, February 16, 2023, at 12:00 pm PT | 3:00 pm ET (60 minutes). Eliyana Adler, associate professor at Penn State University and Atina Grossmann, professor of history at the Cooper Union, New York will discuss the book, I Saw the Angel of Death: Experiences of Polish Jews Deported to the USSR during World War II (Hoover Institution Press, 2022). This event will be moderated by Dr. Katherine Jolluck, senior lecturer in modern East European history, Stanford University.

For over 60 years, the Hoover Institution Library & Archives has preserved the testimonies of more than 30,000 Poles who experienced deportation and imprisonment in the Soviet gulag during World War II. I Saw the Angel of Death is a first-ever scholarly English translation of their stories, more than 150 Polish Jewish survivors offer first-person accounts, allowing a new generation of readers to understand the harrowing experiences of Polish Jews under Nazi and Soviet occupations and in the Siberian forced-labor camps.

>> Katharina Friedla: Good day to everyone online and in our in person audience. My name is Katerina Friede, I'm the Curator of European Collections at the Hoover Institution Library and Archives. I'm delighted to welcome you to today's hybrid book event to celebrate the publication. I saw the angel of death experiences of Polish Jews deported to the US surrounding during World War II, Published by the Hoover Institution Press.

For over 60 years, the Hoover Institution Library and Archives has preserved the testimonies of more than 30,000 polish citizens who experienced deportation and imprisonment in the Soviet Gulag during the World War II. In this first ever scholarly English translation of their stories, more than 170 Polish Jewish survivors offer first person accounts, allowing a new generation of readers to understand the harrowing experiences of Polish Jews under Nazi and Soviet occupations and in the Siberian forced labor camps.

One of the protagonists of this volume, Judyta Patasz, whose picture you can see now on the slide, as well as the original testimony. She fled with her family Poland to Soviet occupied by the German invasion in 1949, from where they were deported by the NKVD to Siberia, where she had lost her parents.

In 1942, Judyta was evacuated with approximately 800 Polish Jewish children, later known as the Tehran children, from the Soviet Union to Iran and later to Palestine, where she gave her testimony to representatives of the polish government in exile. Judyta's original testimony and many others, the so called Palestinian protocols, can be found in the library and archives European collections.

Those original testimonies, the so called Palestinian protocols, and many others can be found in the library and archives. And the basis of the European Collection at Hoover began in 1919, when Herbert Hoover sent his wife, Lou Henry, a telegram stating that he would provide $50,000, almost 800,000 in today's dollars, to underwrite, "A mission to Europe to collect historical material on war".

I today we continue to realize Hoover's vision of collecting, preserving, describing, and making available the most important material about war, revolution, and peace in the world. We thank the overseers of the Hoover Institution, our board of directors, and other donors, without whose support nothing we do would be possible.

And we would also thank our director, Condoleezza Rice, for her support of the library and archives and our programs and publications like the one we are going to discuss today. Last but not least, we also want to express our gratitude to the Susanna Cohen Legacy Foundation for the generous support of this book project, as well as to our colleagues at the library and archives and at Hoover Press for their outstanding work.

And I want to thank also translator of the volume, Carolina Clermont Williams, who made a long journey from London to join us today. My special thanks go to my predecessor, Dr. Maciej Siekierski, senior Curator Emeritus of the European Collections, who initiated the English translation, which goes back to the original Polish publication from 2006, which he edited together with Professor Felix Dischem from the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw.

So for today's book talk, we ask Professor Catherine DeLuca to lead a discussion with Professor Eliana Adler and Professor Athena Grossman. Following to the discussion, we're open for questions and answers from the audience, by which time we will ask our online audience to use the Q and A feature of the Zoom window to submit questions and for our in person audience to raise their hands.

And now let me briefly introduce our three speakers who will be carrying on today's discussion. I will start with our moderator, Katherine Jolluck, senior lecturer in Modern Eastern European History at Stanford University. She's an expert in the history of 20th century Eastern Europe and Russia, with a major focus on the topics of women and war, women in communist societies, the Soviet Gulag, nationalism, anti-Semitism.

She is the author of Exile and Identity, Polish Women in the Soviet Union during World War II, and Gulag Voices Oral Histories of Soviet Incarceration and Exile. Our second speaker is Eliana Adler, an associate professor of history and Jewish studies at Pennsylvania State University. Her research revolves around the modern Jewish experience in Eastern Europe, with a particular interest in the history of education, religion, gender studies and memory.

Her latest book, Survival on the Maldives Polish Jewish Refugees in the Wartime Soviet Union, published in 2020, received many prestigious awards, among others, the Yad Vashem International Book Prize for Holocaust Research. Our third panelist is Athena Grossman, a professor of history at the Cooper Union in New York City.

She is the author of, among others, Jews, Germans and allies, Close Encounters in Occupied Germany 1945 49. She's also co-editor of Shelter from the Holocaust, Rethinking Jewish Survival in the Soviet Union and the JDC at 100 a century of humanitarianism. Her current research focuses on the Jewish Refugees from National Socialism in Iran, India and Central Asia in transnational context.

So, and now I'm turning things over to Professor Jolluck Katherine, the floor is yours.

>> Katherine R Jolluck: Thank you very much. I'm really delighted to be here to take part in the launch of, I Saw the Angel of Death. It's a very important book, and as Katerina mentioned, it offers us for the first time in the English language testimonies of individuals from the largest group of Polish Jews to survive the second World War.

Sometimes they're called the lucky ones. However, they endured extremely difficult and traumatic experiences during the war, but they eluded the grasp of the Nazis, and therefore the genocide perpetrated by them. These Jews were subjected to a different tragedy deportation to the Soviet Union. And ironically, this calamity. Saved the lives of many Polish Jews.

Their stories belong to a long understudied, and I think popularly a little known part of Second World War history, and that is the soviet occupation, or first invasion and occupation, of eastern Poland from 1939 to 1941. The occupation resulted from a secret pact between the soviet government and the nazi government to carve up Poland between the two powers.

And after invading their respective partitions in September of 1939, both powers extended their control over the populations and that involved, in both cases, getting rid of unwanted peoples. So I'd like to start by asking Eliana to just describe to us, who were these polish Jews who were deported into the interior of the Soviet Union, where they came from, and why were they deported?

>> Eliyana Adler: Sure. So briefly, and as we discussed before, we could talk a lot about all of these details, but some several hundred thousand polish Jews Fleda from the part of Poland which had been taken by the Germans to the part that had been taken by the Soviets. And then among that group, approximately 100,000 were deported by the Soviets, along with many other polish citizens who were not jewish.

This was just part of a series of deportations. But for the Jews among them, as you mentioned it, they couldn't have known at the time, but it ended up being their salvation. And essentially, they. There was a moment where they had a choice of accepting soviet citizenship and staying in those incorporated new soviet territories, or in the promise of return to the german held territories.

And they chose the latter. This group did, and it turns out that they didn't really have that option. It was a test, and they failed the test and therefore were deported, whereas the rest of the jewish population, that is, those who chose to accept soviet citizenship and those who were not given a choice, who were residents of that area, over 90% of all of those polish Jews were murdered after 1941 when the Germans invaded.

>> Katherine R Jolluck: Thank you, Athena, can you explain how it came about that a group of Polish Jews, deportees, and refugees were able to leave the Soviet Union in the midst of the Second World War?

>> Atina Grossmann: In the midst of the Second World War, at the height of the war.

And first of all, and thank you so much to Katarina for organizing this, and to everyone for putting out this extraordinary document. Well, the very short answer is with great difficulty. I think the other important thing to note is that this group of Polish Jews, who ended up for these complicated reasons in the interior of the Soviet Union, were already a minority, you know, tragically small minority of polish Jews, of whom only about 10% survived the war and the german occupation.

And the group that we are talking about here, who provided these stunning and almost unbelievably harsh testimonies, were a tiny minority among what was already a tiny minority. That is, those polish Jews who were able to escape the Soviet Union and enter Palestine again at the height of the war in 43 via Iran.

And the reason, just very quickly and simply, is geopolitical developments. June 1941, Operation Barbarossa. The Germans invade the Soviet Union. The polish government in exile becomes an ally of the Soviet Union. Now the Soviets are fighting Germany. That alliance has broken down. And that results in two related events.

The Sikorski–Mayski pact in July 30th, 1941, which is an agreement between the Polish government in exile with its headquarters in London, very influenced also by the British and the Soviet Union, to proclaim what was known as an amnesty. That is to say, provide for the freedom from the labor camps, the special settlements to which these Polish Jews, among many others, had been deported.

And along with that agreement came the promise of the formation of the Polish government in exile army, the so called Anders' Army. Anders was actually just released from prison in order to form this army. And that army was planning to go back to Europe to fight in the european theater.

And they were transiting out of the Soviet Union, out of the south via Central Asia into Iran. And so immediately, many, many polish citizens wanted to join the army. And Jews realized that this was their one opportunity to get out and maybe even get closer to Palestine. And so these are the people who managed, again, at minority among a minority among a minority, maybe 6000 altogether, we're not sure.

Soldiers and civilians, they were able to drag along to work their way into the Anders' Army under great resistance from both Polish and Soviet side. You read all about that in the text, and some of them are able to bring family with them. And there is also this group of about 800 children, the so called Tehran children, who mostly come from orphanages, who are able to join these transports that leave in the spring and summer of 42 and mostly crossing the Caspian Sea.

Some of them also go overland to Mashhad, to Pahlavi, and eventually to Tehran, where they remain for several months and are then again transported ultimately to Palestine. So it's a very long, arduous, complex journey that only a very small group of people managed to succeed in actually accomplishing.

>> Katherine R Jolluck: Eliana, who decided, once these individuals reached Palestine, who decided to collect their testimonies? And do we know much about the process of getting these stories from the polish Jews who had just been evacuated?

>> Eliyana Adler: So it's an interesting question because there's a lot of different kind of developments of this collection of testimonies, and it would appear that the first motivation was to collect material which would be useful with the allies to be able to show the way that the Soviets had treated polish citizens and the military was collected.

Doing exit interviews, and there were questionnaires, and that was happening in Iran, and then it spread, and the ministry of Documentation and Information became involved. And I tend to think over time that it spread beyond its kind of original imperative just for legal purposes and became also partly a way to pass the time.

There was a lot of waiting in all of these places and in Palestine as well, and also a way to keep people engaged with the process of this future imagined Poland coming back. So to get people talking about that and feeling part of that nation. So the interviews with children, and a lot of these in the book are with children, are, I think, part of that effort in the way that it's not obvious that children's testimonies will be useful for legal purposes.

But the ministry was interviewing them in, it would appear that they were being interviewed in Polish and Yiddish. So there were some Jewish journalists who had come earlier to Palestine who were doing some of that interviewing as well, in Yiddish. And then there were Polish non-Jews who were part of the ministry, and Jews, as well, who were working there in Jerusalem who were doing some of the interviewing and collecting this material.

I mean, the exact details of how they did the interviews is not entirely clear, but it is clear that the adults were writing up these materials, and anyone who looks at them will see that they capture some of the children's language, and each one is different. You can tell that they weren't cookie cutter, exactly the same, but it is clear that adults are putting them together, are giving them headings, and it's hard to know exactly how much the children are able to control their own narratives.

I would say.

>> Katherine R Jolluck: Could you also talk about how these documents ended up here at the Hoover institution?

>> Eliyana Adler: Just like the people had to move so much, these documents have also really moved around a lot. So the ministry in Jerusalem was, during the war, sending copies of the testimonies that they were taking to the government in exile in London.

And that's in the archives here, those documents that say, we're sending now protocols 26 through 36. It's clear that some were lost along the way, because, again, if you look through the book, you'll see that the testimonies are, there's polls, they're not all there. And it was fortunate that they were being sent because the documents in Jerusalem mostly didn't survive, whereas those in London did.

And then after the war, I think a combination of the Hoover Institute wanting to collect materials, and the first priority was to try and get, of course, materials from Poland itself, underground and other materials. But there was also an interest in collecting some of the voluminous documentation of the polish government in exile, which, of course, wasn't going to go back to Poland anymore after the war.

And so I wouldn't say that anyone was particularly looking for these documents, but they just got transferred here along with a whole, you know, many, many millions, I don't know, of pages to save them from the communists, essentially.

>> Katherine R Jolluck: Athena, what do you think is the special value of having these documents that were written in 1943?

And what can we gain from them that might otherwise have been lost, say, if these individuals were asked 10, 20 years later about their experiences?

>> Atina Grossmann: I think there's inestimable value to having these very raw as structured as they were. But nonetheless, in real time, as it were, stories from people who are still really in the midst of very traumatic events, although they are now safe, as it were, in Palestine.

But which is yet another step of moving into a completely sort of unfamiliar environment, as yearned for as it might have been in dreams of getting to Eretz Israel. These are, for the most part, young Polish people, children, teenagers, we have former students. And of course, also family members of Polish Army recruits who have been uprooted from homes in pre-war Poland or had seen their homes in what had been pre-war Poland transformed.

Then are deported under kind of with shocking suddenness to the vast interior of the Soviet Union, and are working there under horrendous conditions. Then are suddenly freed and find themselves having to make decisions about where to go. End up in Central Asia or Kazakhstan, on cohouses and overcrowded cities, in what, to them, seemed like an exotic, alien environment.

Then our struggle to be accepted by the Anders army, which is, as I said, extremely challenging. Endure this very terrifying crossing, arrive in Iran, are transported to refugee camps, where they remain for several months, and then picked up again. And transported to yet another location that they had never seen and had only imagined, Palestine.

So for them to be trying to record those experiences at the time is something that is, you know, is really extremely rare. And then to have it not as just individual stories, but in this kind of mass that we can compare and see similarities and differences. On a more general level, I think it's extremely important for us to understand this always vex problem of how do we talk about the horrors of the Holocaust and of the final solution and the extermination of European Jewry?

And to talk about the situation under Stalinism in the Soviet Union in the context of the great patriotic war. And what we see in these stories, and Eliana, actually, you pointed this out in your wonderful article about the testimonies. Is that even though these are texts that were organized by the Polish government in exile, they really want a documentation of how terrible conditions were in the Soviet Union.

That, in a sense, these texts, they evade the agenda, and they tell us about the horrors of the German occupation. They tell us about the terror they endured, the killings, the torture, the difficult decision to flee. And then they give us stories of what it was like to be in the Soviet Union, what it was like to endure hunger, mosquitoes, bedbugs, beatings, terror, but yet not be subjected to systematic extermination.

We get the stories of how individual acts made a difference. If there was a kind commandant, if the relations with ethnic Poles were good or not, if it was possible to somehow maneuver your way into the army. So you get a sense of the kind of contingency of everyday life and the luck and the resourcefulness and the resilience and the desperation.

That, I think, is very, very rare. And we do get side by side stories of these two very different systems under which Polish Jews suffered enormously. And yet under one system, there was the possibility of a much greater possibility of survival. So I think that's really important. And in general, to get the story, we'll get to that question, I think, to get the story into the narrative of the history of World War II, of Jews, of refugees and also actually into the Holocaust, the history of the Holocaust.

Because, as we've said, and as Catherine pointed out at the beginning, this flight to the Soviet Union and the experience there is actually the experience of the majority of Polish, that is to say, also really Eastern European jewish survivors. And that's something that we are very lucky to have such a powerful set of testimonies to inform us.

>> Katherine R Jolluck: Before we talk a little more about their actual experiences, I wonder if, Eliana, you could tell us a little bit about these individuals. Do they come from, like, one social class? I mean, is it a uniform group, or what can you say about level of education, level of religiosity?

Is there something to be gleaned about political leanings, socioeconomics? Is it status? Is it a kind of a cross section or maybe a limited representation of Polish Jews?

>> Eliyana Adler: So the adults who are the minority, but there are some adult testimonies in the book, tend to be those who were evacuated as part of Anders army.

And so they are predominantly male, younger, and were either soldiers or medical personnel, musicians, groups who would be more likely to be accepted into the military, or the dependence of those groups. So that's gonna be a more educated, more secular, although there were some rabbis and religious functionaries also, who were purposely brought along.

So that's gonna be a more sort of narrow group. But the children are everyone. And that's part of what's so remarkable about the children's testimonies. Entirely mixed in terms of gender, in terms of age. They're children from very religious families, from polish speaking families, from families who didn't know Polish at all, from all different parts of Poland.

Their experiences differ. What they've sort of lost differs in terms of their family lives, but in terms of sort of what they left behind when they left Poland. So they're just a remarkably diverse and wonderful group, which gives us a sense of, I think, pre war polish Jewry also.

>> Katherine R Jolluck: Well, I wonder, and this I would ask of both of you, if you can talk about what you found in these testimonies as sort of coming up as similarities. Do you see sort of a pattern in either the experiences that they document or their sort of their attitudes?

Is there sort of an overall theme or preoccupation that comes out of these rather disparate group of individuals? And then maybe the flip side would be, are there any that just stand out to you as just, you'll never forget having read, you know, someone's testimony? Because I know I had that experience in my own research, that there are individuals whose experience and way of writing about it will stay with me forever.

So I wonder if either of you would like to comment along those lines.

>> Eliyana Adler: Sure, yeah, that was a lot of questions. Let's see, similarities. I think the very kind of straightforwardness of children that they whatever it is that they've experienced, they just describe. They don't have shame, they don't have.

They're not trying to necessarily cover something up. They're just talking about what they experienced. And sometimes I think what stays with me the most are the most emotional moments where they describe this is just day to day, this, and then my father died and then we weren't able to bury him.

And then my brother died while he was trying to find a place to bury him. And that sort of description is everywhere. But if I could. Yeah, just remember one that really stayed with me. A teenager describes that his mother, on foot, followed the transport that was taking him out of soviet central Asia toward Iran for 7.

Then he says to the interviewer, I don't know if she knows how to find me here or if I'll ever see her again.

>> Atina Grossmann: Yeah, I mean, there is a kind of sort of horrifying similarity in these testimonies, which is this sort of laconic accounting of terrible, terrible hardship.

It's about hunger, it's about disease, it's about standing on line. It's about the uncertainty of, am I going to be able to get myself into this transport, where are we going next? And then this sort of roll call of deaths where it's like we were a family of seven and now there are two of us here, my brother and I.

And so the death, it's not total, that's the difference, but it is just sort of stunning in its frequency. So that's kind of the horrible sameness. And then there are these moments of. The agency of resourcefulness, of descriptions. One thing that stayed with me, so the gender historian, is the descriptions of protests, of strikes in the labor, in these soviet labor camps which sometimes actually worked.

That's another distinction between, say, the experience in the Soviet Union and under nazi occupation. For example, if people were forced to work on jewish holidays but also transfers from one camp to another, or family separation. And frequently it is said that the women were the most stubborn. One testimony says the women were the most stubborn.

And it comes up actually several times that somehow the women are seen as those. Perhaps they were considered to be less endangered if they protested. So that these moments of really trying to fight for survival and the ability to try to use every possible resource, to use connections to ethnic poles, to people in the government, in exile, in the army, sometimes it worked.

Very often, you know, very often it didn't work, so those moments strike me. And then the third thing which is particularly interesting to me as someone who works on the part of the experience that isn't mentioned here, that is interestingly silent, even though it's already happened, are the months in Iran, for example.

So what isn't discussed is that whole in between experience. I mean, we tend to think of these moments in, quote, unquote, exile as in between. But then there's the extra in between what was frequently months, somehow between two, up to seven, eight months that these children and also the adults who are giving testimonies spend in Iran.

And almost every testimony ends. And then we arrived in Iran. We went to Tehran, and now I came to Palestine. I mean, almost every testimony ends like that. So there are these whole pieces of experience that do not seem important or they weren't important to the interviewers. And I could, of course, say something about what that time in between was about because a great deal happened.

And I'll just sort of give you one image. And then, which I actually only literally just saw the other day in a film made by the Polish government in exile about, really the Polish army arriving on the shores of Pahlavi on the Caspian and the reception. And there's a child in this film, it's part documentary, part feature, but who finally gets to a refugee camp outside of Tehran, where he spends months along with hundreds of other children.

And there's a street side in the camp and it reads, these are familiar images from, I think, especially when we're talking about refugees. And so one sign says Tehran, 3 km. These camps are a little bit outside and sort of right at the shadow of Mount DEmaVend ANd the mountains around Tehran.

Tehran 3 km other direction Warsaw 4326 or 4621. And so that's the world that they are in. And in some ways, the over 4000 WaRSaw, even though many of them will never, ever get back to Warsaw, are closer in terms of their experience in Iran than the 3 Tehran, although there is quite a bit of contact, which we don't have time to talk about here.

But I think that also really stuck with me, that coda. So it's about what we learn from these testimonies and also about how we think about what they don't tell us.

>> Katherine R Jolluck: Eliana, I wonder if you could talk about what we can learn from these documents about relations between the ethnic Poles and the polish Jews in deportation and.

And even that last period of trying to get out of the Soviet Union and then making their way to Iran.

>> Eliyana Adler: Yes, and I think this in many ways speaks to the integrity of the sources in that. Here's the polish government in exile ministry of it, collecting these materials for the purposes to a great deal of showing just how terrible the Soviets are.

And in many, many of these documents, the children are talking about sometimes good relations, but often horrific relations with ethnic Poles, with catholic Poles. And that that appears in these documents, I think, really speaks to that. They really were noting down what they were listening to from these children.

And also in the archives, one can see that there were actually ministry officials who were going through and sort of marking on a checklist. This one has antisemitism, this one has hunger, sort of different experiences that are common. And one of the things that I didn't mention before, when you had asked about some of the reasons these were being collected is additionally the polish government in exile in London, Washington, getting pressure in London and from the United States as well, about antisemitism in Anders army, in the polish delegates in the Soviet Union.

So they wanted to be able to find positive examples. And there are. And there's some, you know, some very beautiful ones. For example, one testimony I remember talks about how the. The camp, the person in charge of this particular labor camp was, the child describes as hated Jews, but hated Poles even more, and that the polish Jews and non Jews would help one another as they were collectively dying off of hunger in these camps and of overwork and on the accidents because of the poor labor conditions would sort of COVID for one another as they would perform their different religious burial rituals and help each other to be able to do that.

So there's some very meaningful, beautiful examples, but I think there are more examples, certainly in my reading of antisemitism going on in the the recruitment and acceptance into the Anders army, and from the children's perspective, very much in the orphanages in which they were placed, which were then, they were then taken out in those orphanages and children describing.

Not just getting beat up by other children, but the staff of these Polish orphanages denying them food and kicking them off of the transports at the very last second, and some really terrible moments. So we see a spectrum, and I think a sense of the difficulties and the competition for resources and the entrenched distrust is all there in the documents.

>> Katherine R Jolluck: Atina, I'd like to ask you if you could reflect on why you think it's important for scholars to include and consider the experience of Polish Jews who went to the Soviet Union during the war and these who made it out. Why it's important to consider that as part of the Holocaust and what you would say about the import of that.

>> Atina Grossmann: Yeah we're part of that project, Katherine, as well. It's been difficult, and it's been a long process. It certainly started, actually, already decades ago. It's just that really, in the last ten years plus, has it become part of the scholarly conversation again. And now, I think, slowly also moving its way into public memory, and in particular, also into commemorative rituals, as well as, very, very importantly, museums, which, in a sense, really define the public memory of the Holocaust.

And I think the first reason why it's important is that it reshapes our sense of who the survivors of the Holocaust actually were. And we always talk about the survivors. And, I mean, when I started working on Jews in displaced prison camps in post-war Germany, I actually did not understand that the great majority, that's how I got into this subject in the first place, cuz I was not trained as an Eastern European historian.

That the great majority of the people I was writing about and whose experiences I was chronicling, the Sh'erit ha-Pletah, the Sh'erit ha-Pletah, the surviving saved remnant of European Jewry. That the great majority of those people, whether they were settled in the recovered territories of Poland and in Silesia as repatriates from the Soviet Union to the newly constituted Poland after the war.

Or whether they ended up in displaced persons camps and allied-occupied Germany and Austria after having been repatriated and then had to flee again after the war. That those people had survived precisely because they had escaped, sometimes quite unexpectedly and involuntarily, had escaped Nazi occupation. And that that was why we had survivors.

And I think a lot of, in a sense, resistance, especially among Jewish studies scholars, Holocaust studies scholars, to opening up the story, and also the fear, in a sense, of these flight survivors themselves, was that it would overshadow the central story of the final solution and the extermination by the Nazis.

But the more I studied this, the more I felt like it was actually underscoring the virtual totality of the final solution under Nazi occupation. In that the 250,000, say, survivors, we have then gathered in the displaced persons camps and in the refugee communities of allied-occupied Europe. When the Germans looked at all these Jews suddenly appearing, or Poles, for that matter, trainloads of Jews after the war and said, wait a minute, we thought there had been an a final solution.

Those people, 250,000 Jews, did not walk out of Treblinka, nor did they come from the woods and the partisans or from passing on the aryan side. Those were for the most part, people who had been in the Soviet Union. And to understand that experience, I think, is absolutely central to the way we tell the story of the Holocaust.

It doesn't displace, obviously, the centrality of death or the survival of those who did manage to endure under Nazi occupation. So I think it tells us a great deal about the way that the Holocaust unfolded. It has now become part of what we in Holocaust studies have called a kind of globalizing the history of the Holocaust or remapping it.

I mean, we're now expanding our map to refugee locations all over the world, from Iran to the Dominican republic or Kenya or India. But it also pays attention to the role of geopolitics, the role of the Soviet Union, the importance of transnational Jewish support, the importance of the Yishuv of Palestine as a rescue destination.

It simply opens up this history as part of the history of World War II in general, part of the history of refugees. It makes it both more and less, I think, comparative. So it's very important.

>> Katherine R Jolluck: Thank you. For my last question, I'd actually like to turn to the translator, who, I hope you can see the size of this book, who translated all of these documents.

And, Karolina, I'd just like to ask you what it was like to translate these testimonies. And were there any special challenges that you encountered in doing this work?

>> Karolina (Translator): Thank you, Katherine. So the main thing, I think it would be interesting to reflect on, which inevitably, we touched on in the discussion, is just how many layers of interpretation these people's lived histories, so actual things that happened to them, have had to go through for us to have this book here.

And this is something that inevitably, as a translator, I have thought about every day on this project. So first, we've got something that Eliana, I think, touched on, so the lay of memory. So these people, reaching back those few years to remember those events, then we have the act of collecting these testimonies.

So interviewers and how that, again, affects what is remembered and what actually ends up on the page. And then the great honor that I had, which is the last layer of then translating that from Polish to English. So I think if I were to summarize my experience working on this project, which took me the better part of two years, it's this heavy responsibility that I felt on my shoulders in working on this.

I think it's a project that will stay with me forever in the best way possible. And as much as I regret that it's a truism to say now seems like a time when this work is particularly crucial.

>> Katherine R Jolluck: Okay, now I would actually like to open it up for discussion and questions from the audience.

And let me just remind the people who are joining us via Zoom that you can also ask questions and they will be passed on to me. But let's start with Norman.

>> Norman: Thank you. That was great. Thank you so much for coming. And it was a wonderful panel and I learned a lot.

Thanks. Really. It was really eye opening in a lot of ways, even though I know the documents and I've worked with them. So if I can, I'd like to ask one sort of fat question. Maybe not so fast, but try to be fast question of each of you.

Eliana, I haven't had a chance to read your article, but you've explained a lot about this sort of question I'm interested in, which is the extent to which, in some senses, these documents are censored. And if you could bear down on that question a little bit. I mean, you talked about it, but it's unclear to me just how much they were censored.

I just don't know. And so, to the extent you can tell us that. Athena, I was particularly interested in your remarks about these Polish Jews, more or less as Zionists. I mean, you expressed they wanted to get there at Israel. My memory of the documents and reading them was not that.

And I wonder where that comes from. And then this question you asked yourself, or you posed to us about what happened to them in between the time they were in Iran and in Palestine. And here I was thinking about the British, who really didn't like Jews to come to Palestine, as you know all too well, both before and after the war and during the war, it wouldn't have been any different, right?

And so why did they even send them there in the first place? And in the second place, are there british documents that tell us much about this? In other words, wouldn't we be able to learn something from the british archives, perhaps about the status of the Jews in between the time they were in the Soviet Union and when they came to Palestine?

And finally, the Jews themselves, these polish Jews themselves, did they change when they came to Palestine? Did they become, in some sense, a zionist? And where did they end up? My memory is. And again, I don't know exactly. Most of them left, but I don't know for sure.

So those are my questions.

>> Atina Grossmann: Okay, I think-

>> Eliyana Adler: Should I start-

>> Atina Grossmann: With the censorship?

>> Eliyana Adler: Okay, great. Thank you. Yeah, I guess I wouldn't use the word censorship, but certainly mediation. I mean, these, as you know, I'm sure from working in these documents that the Hoover Archives does have some of the questionnaires that were taken by the military in Iran, for example.

You can actually see the handwriting of the soldiers who are answering each question. And that we don't have, we will never find if there was an original, even of these, maybe it was just a conversation which was then written up as an essay afterward. So it's hard to know exactly how much mediation, but I think we need to understand that the adult is controlling this narrative, what we have in our hands.

And to Karolina's point about the kind of multiple translations, I would add that we also don't know how many of these were originally taken in Yiddish and then were translated into Polish before they were sent to London. So it could be that you're translating a translation of a mediated text, because some of the Yiddish, a handful of the Yiddish originals are in an archive in Bnei Brak in Israel.

And so we can compare them, and they're not greatly different, but it's fairly clear to me, I mean, logically, that there wouldn't have been any point in translating back into Yiddish. So I think that those that we have the Yiddish of definitely were originally taken in that language.

So it's hard to say. But I do think that the. I mean, they're different, the children, some of them are more laconic, some of them are more sarcastic. Some of them use kind of turns of phrase that feel like quotations, even though they're not in quotations. So you definitely get a sense of some personality in the text, even though it's hard to know how much.

>> Atina Grossmann: Yeah, it's also, I think, very interesting to compare these texts to later memoirs and later testimonies, of which we have a remarkable number. And once historians started getting attuned to the importance of this question. There's a huge amount of material actually to draw on. Now in terms of your question about the status of Zionism and the desire to go to Palestine.

Well, we're dealing here with two specific, and as I said, minority within a minority groups of Jews. One are the men who were able with great difficulty to make their way into the Anders army, sometimes bringing family members with them. And the other group is the children. So I think that for those people who joined the Anders army, I do think that it was only a minority.

And that was part of what the polls said was the reason that they didn't want to accept the Jews, that they were going to, you know, they were disloyal potentially. They weren't real poles. Only for a small group was there this desire to fight as patriotic Poles for the fatherland.

And indeed, there were those who continued on all the way to Monte Cassino and became heroes of the fatherland, in many cases dying for that cause. But it does seem, and statistically it's borne out, that the majority did have in mind exactly what they were suspected of, which was.

That they knew that the Anders' Army had to pass through Palestine and that that would be an opportunity to desert. The most famous deserter, of course, is Menachem Begin. He always insisted that he didn't really desert, but he certainly left. So I would make the distinction between a desire to get to Palestine as an imagined, at least, safe haven and a way out of the Soviet Union and having some sort of zionist ideology.

Although the influence of zionist youth organizations and zionist political parties, as well as the Bund in the Soviet Union among Polish Jews was significant, that was one of the things that was important about being in Central Asia. There was still this opportunity to maintain networks for the children.

Just very quickly, their children, they're in these orphanages. They are picked up and plucked, or the surviving parent puts them into an orphanage so that they have a chance of survival. By the time they arrive in Palestine, they have been trained, they have been socialized, they have been, if you will, indoctrinated.

However, they have become little jewish scouts. They have had their. The emissaries from Palestine have been sent to Iran to train them, to teach them, to start talking to them about this magical place that they are going to come to. So I would say yes. By the time they arrive and they're questioned and they're asked to write, to contribute to their own stories, they have learned a great deal, and they have marched, and they have heard stories, and they have started to learn Hebrew about this land to which they are going.

Again, this is a very small group, but, yes, I would say that Palestine is extremely important. I would love to say more, if we have time, about what happened in between. But one thing that happened was a lot of zionist training.

>> Katherine R Jolluck: Thanks, our next question will come from the online audience.

>> Katharina Friedla: Yes, so, unfortunately, our time is running out. We've got a lot of questions via Zoom chat. We will answer them later. But I want to address one question from Steven Schreier. He asked, do you observe any similarities to the tragic Holocaust events of World War II happening again today with Russia's war in Ukraine?

>> Eliyana Adler: I mean, it's certainly, one can't, at every single location that we hear things happening in Ukraine. I think for those of us who study the Holocaust, there's all these layers of meaning to them. What happened in Kherson or Kharkiv or all of these places, Kyiv. So there's that resonance happening at every time, hearing about these places and certainly hearing about massacres in these places, about deliberate attacks on civilians.

All of that is all too familiar. But it's a different war under different circumstances in which, yeah, with different players. And so I also think we have to be aware of. Of those factors, but certainly very tragic and terrible what's going on in the human loss.

>> Atina Grossmann: Yeah, I guess I would simply say that one of sort of the horrifying aspects of the current war is this complete misappropriation of the term great patriotic war, or antifascist initiative on the part of Putin's Russia against Ukraine.

And simply to note that, I mean, the notion of the great Patriotic War and the role of the Red Army in defeating the fascists was something that certainly in later memoirs, plays a really significant role for the Polish Jews. And again, I would say especially for children who are sometimes able to go to school if they're not out spending all their time trading or being sick or caring for sick and dying family members.

So they do follow the war. They do put little marks on the map. They do identify with the progress of the Red army, even as they are being repressed and terrorized at times and sharing in the hardships. So I think for us to think about the meaning of that great patriotic war in all of its multiple contradictions, as experienced, particularly behind the lines on the Tashkent front, and the ways in which that history is just being so criminally misread and misused, is perhaps something that we can learn also from these texts.

>> Katherine R Jolluck: Since we have a large online audience, we will need to wrap up soon, formally, although those of you who are in the room can continue to stay and ask questions after sort of the formal end. Right now, I would like to, of course, thank Atina and Eliana for sharing their expertise and insights into this very important book and the history behind it.

And I wanna turn it back over to Katerina.

>> Katharina Friedla: So thank you so much, Katrina. Thank you, Eliana, Atina. Thank you, Karolina, for your lively and really extremely stimulating discussion. And thanks to everyone for having join us virtually and in person. I would strongly recommend everybody in the audience to acquire and read this incredible, moving collection of testimonies.

And want to add that the Hoover Institution Press is offering a 30% off discount code when ordering through Hoover Press bookstore, which is valid through February 28. Thank you, everyone, for being here. We hope you enjoyed our discussion, and we look forward to seeing you again at one of the Hoover Institution Library and Archive's upcoming events, which are listed on the screen.

Thank you so much and goodbye.

PARTICIPANT BIO

Eliyana Adler is an associate professor at Penn State University and historian of the modern Jewish experience in Eastern Europe with particular interests in the history of education, religion, gender studies, Holocaust historiography and memory. Adler has co-edited volumes on the history of Jewish education in Eastern Europe, the memory of Eastern Europe in the American Jewish community, and family and the Holocaust. Her latest book, Survival on the Margins: Polish Jewish Refugees in the Wartime Soviet Union (Harvard University Press, 2020) is the first English language scholarly book to describe the experiences of the over 200,000 Polish Jews who survived the war and the Holocaust in the unoccupied regions of the Soviet Union.

Atina Grossmann is a professor of history in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the Cooper Union in New York City. Her current research focuses on “Trauma: Privilege, Adventure in Transit: Jewish Refugees from National Socialism in Iran, India, and Central Asia in Transnational Context.” Her book Jews, Germans, and Allies: Close Encounters in Occupied Germany (Princeton University Press, 2007, German, Wallstein 2012) was awarded the George L. Mosse Prize of the American Historical Association and the Fraenkel Prize in Contemporary History from the Wiener Library, London.

Katherine R. Jolluck is a senior lecturer in modern East European history at Stanford University. She is a specialist on the history of twentieth-century Eastern Europe and Russia, she focuses on the topics of women and war, women in communist societies, the Soviet Gulag, nationalism, anti-Semitism, and human trafficking. Interested in public service, she offers service-learning courses and is active in the Bay Area anti-trafficking community.