By Issayas Tesfamariam

There were many important battles in World War II (WWII) which occurred in the European and Asian theatres, respectively. However, there was also another important theatre of battle in WWII which is still not well known: Africa.

World War II is often discussed primarily through the prism of the conflict in Europe that started in 1939, with the discussion of African campaigns centering on operations in North Africa. Yet holdings at Hoover Archives show that the conflict in Africa spanned the entire continent. Putting WWII in the pre-war international context, it could be argued that 1) Benito Mussolini’s invasion of Abyssinia (later Ethiopia) in 1935 was an augury and 2) the beginning of the end of WWII – what British Colonel A. J. Barker called “our first real victory of the Second World War”- started in the Horn of Africa in 1941. The purpose of this article is to showcase Hoover’s possession of rare collections relating to both events. Just a brief comment on the first argument. Professor Richard Pankhurst argues that at the conclusion of the war in Europe, Italy and the United Nations signed a treaty in which all parties agreed that the World War II in Ethiopia began with Italy’s invasion of the country on October 3, 1935.[2]Hoover’s rare collection relating to the Italian-Abyssinian War, 1935-1936

The Ruth Ricci Eltse collection at the Hoover Institution Archives has correspondence, writings, photographs (including an album of photographs of Benito Mussolini and photos of Italian dignitaries and military leaders) relating to the Italian-Abyssinian War, 1935-1936.

Brian J. Griffith, a PhD candidate at the University of California, Santa Barbara, has used the aforementioned collection at Hoover extensively for his upcoming edited volume entitled: Sorella Fascista: The Collected Papers of Ruth Williams Ricci.

From the 1930-1940 period:

A telegram sent in 1936 from Duca (Duke) Amedeo D’Aosta (signed by his secretary) to J.E. Gasparini. (Note: Duke of Aosta was the Viceroy, Governor General and Commander in Chief of Italian East Africa/Africa Orientale Italiana [A.O.I.]) Duca (Duke) Amedeo D’Aosta replaced Marshal Rodolfo Graziani. D’Aosta surrendered to the British forces in Amba Alagi, Ethiopia on May 18, 1941 thus ending the era of Italian East Africa (Eritrea, Ethiopia and Italian Somaliland).

A telegram sent from Marshal Rodolfo Graziani to Engineer Andrea Fontana in June 1937. (Note: Marshal Graziani was the Viceroy of A.O.I. After an assassination attempt on his life in Addis Abeba, Ethiopia, in February 1937; Grazini ordered the massacre of thousands of people. Ian Campell has written extensively on the subject in a book entitled The Addis Ababa Massacre: Italy’s National Shame.)

A telegram sent from Marshal Emilio De Bono to Gasperini in 1939. (Note: Marshal De Bono was the Supreme Commander of Italian forces against Ethiopia in 1935. He stayed in that capacity until he was replaced by Marshal Pietro Badoglio in late 1935.)

A letter written by Dr. Malaku E. (Emmanuel) Bayen to Suffragist, Mrs. Gillett-Gatty and a September 14, 1940 issue of “The Voice of Ethiopia “(New York), organ of the Ethiopian World Federation. (Note: Dr. Malaku E. Bayen was a US educated Ethiopian physician who established the Ethiopian Research Council. Dr. Bayen was an anti-colonial and Pan-Africanist organizer.)

Hoover’s rare collection relating to the 1941 Allied Military Campaign in the Horn of Africa

In early 1941, Allied forces attacked Italian forces in the Horn of Africa. According to Colonel Barker, three parallel series of operations were going on at the same time: the attack from the north (Sudan) to Eritrea under the command of General Sir William Platt; from the south (Kenya) under the command of General Alan Cunningham; and limited military operations staged by the Ethiopian Patriot Forces (under the command of Brigadier Sandford along with the controversial figure of Orde Wingate).[3]On April 1st 1941 -seventy-seven years ago- the British and French forces along with soldiers from their respective colonies defeated Mussolini’s forces and entered Asmara, the capital city of Eritrea (located along the Red Sea coastline), Italy’s “prima-genita”/ “first-born” colony and its prized possession. And on April 8th 1941, the same forces entered Massawa, the Eritrean port city on the Red Sea coast. Rear Admiral Edward Ellsberg was commissioned by the United States Navy (USN) to salvage the ship wrecks and to make the naval base in Massawa, Eritrea, reusable. In his book, Under the Red Sea Sun, Rear Admiral Ellsberg had the following to say about the destruction in Massawa:

In the three harbors of Massawa waterfront and its off-lying islands lay

a fleet of some forty vessels, German and Italian freighters, passenger

ships, warships, crowded every berth which in addition, in the north harbor

were two irreplaceable floating steel dry docks. A tornado of explosions

swept Massawa waterfront as exploding bombs, strategically placed far

below their water lines, blew out the sides and bottoms of ships by the

dozens. The invaluable machinery in the naval shops were smashed with

sledge hammers. Electric cranes were tipped into the sea. Everything in the

way of destruction that Italian ingenuity could suggest to make Massawa

forever useless to its approaching conqueror was painstakingly carried

through. When the last bomb had gone up and the last ship had gone down,

the Italian Admiral (Bonnetti) commanding rubbed his hands in satisfaction

over such a mass of scuttled ships as the world had never seen before. Then

he surrendered Massawa.

Note: Rear Admiral Ellsberg was the uncle of Daniel Ellsberg of the “Pentagon Papers”.

For my extensive interview with Todd Pollard, grandson of Rear Admiral Edward Ellsberg, check out:

In 1941, the Italian forces heavily defended a limited number of towns (Keren being the most defended) in Eritrea during General Platt’s advances. Barentu, Agordat and Massawa were examples. Keren, according to Colonel Barker, was the supreme Italian effort and performance of Carnimeo’s (General) troops there has probably never been surpassed in Italian military history.

From this period, Hoover has:

1) a six-page proposal to award a medal of honor to Sergeant Major Giuseppe Pistone a member of the 22nd Battalion of the Colonial Army of the A.O.I (Africa Orientale Italiana) for his role in the defense of Barentu, Eritrea. The petition’s recommending officer is Lt. Colonel Francesco Mancuso, commander of the 22nd Battaglione Coloniale (A.O.I.),

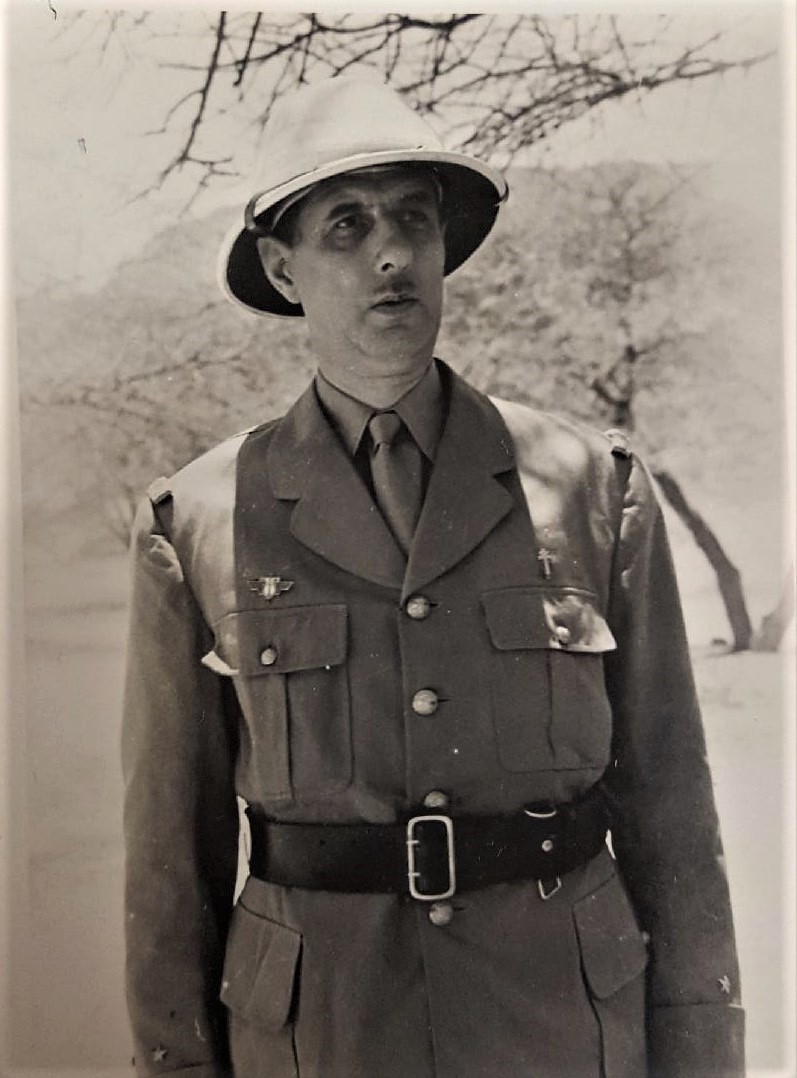

2) the Graham C. Dorsett Photograph collection which depicts the Indian (also Pakistani) Army in Italian East Africa. The collection has over 2000 photos and shows the advances and victories of the army commanded by General Platt. The pictures include General Charles De Gaulle’s visit to the British and Free French forces in Eritrea.

So, why were the Allied Forces in the Horn of Africa, in general, and Eritrea, in particular, in 1941?

The short answer is a geographic (strategic) location: a case of geography’s notable role in history and for the longer answer, I will refer to various sources.According to Commander John D. Alden, the Red Sea is probably the most forgotten theatre of fighting in WWII, and its significance during the early years of the war has been largely ignored.[6]Douglas Porch argues that the Eritrean campaign opened the Red Sea so that U.S. merchant shipping could supply Suez (Canal). Without the opening of the Red Sea these ships would have to travel thousands of miles around the Cape of Good Hope.

According to John W. Swancara,

By the Fall of 1941, Britain was being pushed to the brink of disaster

in North Africa. Time was running out and so were the combat ready

planes of Britain and its allies. Churchill asked Roosevelt for “some

help.” Roosevelt responded by authorizing a secret Air Depot to be

established and operated by American civilian volunteers under the

direction of Douglas Aircraft Company. It would be classified “Secret”

and given the title of “Project 19.”

What was the highly classified Presidential Directive called “Project 19” and its impact on the war?

According to Peter J. Schraeder,

The War Department’s efforts in Eritrea were two fold. First, in the

aftermath of a secret meeting held in Washington on November 19, 1941,

a Royal Air Force (RAF) support base was established at the Eritrean town

of Gura. Codenamed “Project 19”, the purpose of the base was to repair

and return damaged RAF aircraft to the North African battle zone with

“minimum delay”. The War Department also refurbished the Eritrean port

of Massawa to provide direct support for the British Mediterranean fleet,

as well as to maintain a naval salvage operation to raise over forty ships

scuttled by the Italian Navy.

Note: The personnel destined for Gura, Eritrea were recruited from various professions including engineers from the aerospace industry, physicians, nurses, cooks and etc. The airplanes repair part of Project 19 was assigned to and under the direction of Douglass Aircraft Company. The logistics and construction component of the project was assigned to Johnson, Drake & Piper. For a complete sociological study of the project in Gura, see E. Gordon Ericksen’s Africa Company Town: The Social History of A Wartime Planning Experiment (1964).

By the end of 1942, according to John W. Swancara, fifteen ships had brought 2,106 project employees. One of the first ships to arrive to Eritrea was the Army Transport SIBONEY. It left Brooklyn, New York on Christmas Eve, 1941 and arrived in Massawa, Eritrea, on February 2, 1942.

Hoover Institution Archives has newsletters issued on Army Transport SIBONEY. It has a complete run of the “The Trailblazer,” a rare hand typed daily paper under the editorship of Thomas Hubbard Vail Motter. “The Trailblazer”’s contents include: War (News) Flashes, Radio News, Letters to the Editor, Society Notes (Birthdays.), Entertainment (movies, poems, jokes, tournaments.), Ship’s News and Notes (Community Laundry, Lost & Found.) and Logs of the Voyage Given by Daily Keepers.

According to T.H.Vail Motter, quoting him in detail, Army Transport SIBONEY carried 600 members of three military missions and some fifty million dollars’ worth of irreplaceable construction equipment, she got through the submarine infested Caribbean and across the South Atlantic unescorted and without incident except for a false submarine scare in the Indian Ocean.

The SS OKLAHOMAN was not as lucky as the SIBONEY. According to John W. Swancara:

some ships never made it due to German submarine activity. One loss was

the SS OKLAHOMAN whose sinking was referred to by General Brereton

in his personal dairies. Quote; “The loss of this ship and cargo will set

Project 19 back at least six months.” … A second ship carrying crucial

tools, test and calibration equipment and complete Army photographic

laboratory is lost in the straits of Madagascar.”

Even though “Project 19” was highly classified operation, John W. Swancara states that it was reported that during one of the early convoys to Massawa, Lord Haw Haw, the notorious ex- British Nazi propagandist, in one of his many speeches, included the convoy size, speed. and direction and commented that “Your ships will never make their destination.”

In conclusion, Hoover’s holdings on the time period covered would help researchers investigate into what Commander Alden called the most forgotten and largely ignored theatre of fighting in WWII, and its significance during the early years of the war.

[1] Sources:

Barker, A.J., Eritrea 1941 (London: Faber and Faber Ltd., 1966) 17

[2] Richard Pankhurst, “Italian Fascist War Crimes in Ethiopia: A History of Their Discussion from the League of Nations to the United Nations (1936-1949)”, Northeast African Studies, new series, 6 (1999), 109-111

[3] Barker, A.J., Eritrea 1941 (London: Faber and Faber Ltd., 1966) 17-18

[4] Ellsberg, Edward. Under the Red Sea Sun (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1946) 11

[5] Barker, A.J., Eritrea 1941 (London: Faber and Faber Ltd., 1966) 209

[6] Alden John, D., Salvage Man: Edward Ellsberg and the U.S. Navy (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1998) 129

[7] Porch, Douglas. The Path to Victory: The Mediterranean Theater in World War II (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2004) 663

[8] Swancara, John W., Project 19: A Mission Most Secret (Spartanburg: Honoribus Press,1998) 13

[9] “Project 19” also had a sister project named “Project Cedar” whose purpose was to deliver aircraft to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.) through Iran.

[10] Schraeder, Peter J., United States Foreign Policy Toward Africa: Incrementalism, Crisis and Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994) 115

[11] Swancara, John W., Project 19: A Mission Most Secret (Spartanburg: Honoribus Press,1998) 36

[12] Ibid. 37