By Nana Osei-Opare

On March 6, 1957, the first African socialist revolution commenced. With an estimated population of six million, the tiny new country, Ghana, captivated the globe’s attention. Its first prime minister, Kwame Nkrumah (1909-1972), confidently claimed that Ghana would “show that after all the black man [wa]s capable of managing his own affairs.” As those words reverberated around the globe, many—soaking in the occasion and the possibilities at hand—cheered while dancing to the rapid cadences of highlife music. Yet, on February 24, 1966, almost nine years after the euphoria, Nkrumah—the unflinching Pan-Africanist and the Black world’s messiah—was overthrown in a relatively bloodless coup d’état. Nkrumah’s statues were destroyed, and his ‘followers’ denounced him. What happened to Africa’s first socialist revolution? Had Nkrumah proved Africans incapable of managing their own affairs? With a predominantly agrarian-centric export-based economy, whose prices were tied to the international market, was Ghana, alongside many other post-colonial African states, set-up to fail? Had the revolutionaries, as C.L.R. James noted, “failed to create the new society?”

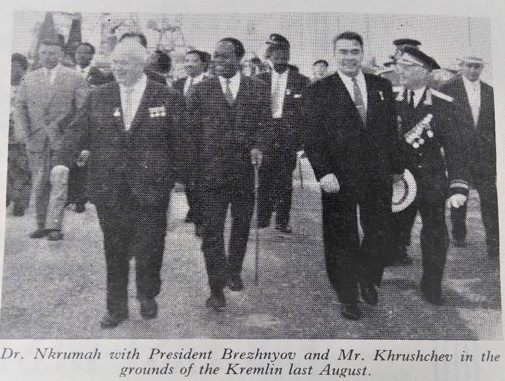

To better appreciate the first socialist African revolution, the coherency of Nkrumah’s ideas, and the Ghanaian project, my dissertation, tentatively titled, “‘Forward Ever’: Post-Colonial Capitalism and Socialism in Ghana, 1957-1966,” re-evaluates this period by re-historicizing the Ghanaian revolution, and by re-thinking both the underlining logics of Nkrumah’s economic policies and intellectual development, and Ghana’s economic and state-building methods in relation to the Soviet Union’s New Economic Policy (NEP) (1921-1928). “‘Forward Ever’” argues that NEP provides a critical framework to comprehend the Ghanaian revolution, one which profoundly shaped the Black world’s consciousness. The NEP schema provided the intellectual elasticity that permitted Nkrumah, the Ghanaian state, and other postcolonial leaders to denounce capitalism, construct complex socialist visions and realities while co-opting capitalism and capitalist enterprises. In this sense, my project seeks to understand NEP’s relationship to Nkrumah and Ghana in two different registers. First, it explores how NEP came to influence Nkrumah’s thinking. Second, based on this influence, it considers NEP as an analytical framework to comprehend the Ghanaian state and revolution from 1957-1966. More than looking at NEP’s legacies in Ghana’s history, “‘Forward Ever’” is also interested in Ghana’s relationship with the Soviet Union during Nkrumah’s era. Some of the questions I am thinking about are: what contours did the Ghana-Soviet relationship take? How much agency did the small black state have in this relationship? Furthermore, how did race and racism shape Cold War politics and nation-state relationships?

Hoover possesses an extensive but often overlooked collection of materials about Ghana (1957-1966), Ghana’s relationship to the Soviet Union, and global discourses on racism. These documents allowed me to think about the role of race and racism differently. At Hoover, I came across two events that made me question my prior assumptions about the role race played in Ghana’s relationship with the Soviet Union and the Cold War. There is an infamous story of the death of a twenty-nine-year-old Ghanaian medical student, Edmond Asare-Addo, in December 1963, in Moscow. While the Soviets claimed that Asare-Addo drunk himself to death, the Ghanaian students maintained that Asare-Addo’s death was racially motivated due to his impending marriage to a white Russian woman. In response to Asare-Addo’s death, Ghanaian and African students protested in the Red Square, carrying numerous placards. One read: “‘Moscow, a second Alabama.’” I had initially thought that the reference to Alabama was simply symbolic of white racism: segregation, lynchings, and discrimination.

At Hoover, I found newspaper articles that made me rethink that assumption. Rather than merely equating Moscow and Alabama to racism, the Ghanaian students in Moscow were referencing a specific incident that happened a few months before Asare-Addo’s death in Alabama. Near Tuscaloosa, Alabama, five white men steered their car deliberately into a vehicle containing three Ghanaian college students, drove them to an isolated spot, and physically assaulted them with a pistol, clubs, leather belts, and automobile tools. In early 1964, an American journalist quizzed the Ghanaian Envoy to the U.N. about whether the Ghanaian government would continue to send Ghanaian students to the Soviet Union due to Asare- Addo’s mysterious death. In response, the Ghanaian diplomat remarked that it is a tragedy and a serious issue when a Ghanaian student dies “mysteriously;” however, that since Ghana was a “third world country” that it did not have the luxury not to send its students abroad to educate them rapidly. Furthermore, the diplomat reminded the American journalist that Ghanaian students had recently been assaulted in Alabama and questioned whether the same journalist would recommend that Ghana not send its students to America anymore? The issue of race and racism and its role in global politics was even more telling when United States Vice-President Richard Nixon refused to say that there were any bad colonial regimes during his visit to Ghana’s Independence Day celebrations on March 6, 1957. These were vital moments and questions that shaped how African students and diplomats understood racism as a global phenomenon that cut across the Cold War binary.

I was blessed to be a Silas Palmer Fellow during the 2017-2018 academic year. The fellowship provided me with the financial and institutional support to carry out my dissertation research. The Hoover archivists and staff were extremely courteous, helpful, and knowledgeable. They never sought to stifle or hinder my research. In fact, they went out of their way to help me locate useful files and texts—an archivist even scanned a book they thought I might find useful and emailed it to me after my research stint. The staff hosted a volunteer weekly coffee break to get to know the researchers and their work better to be of better assistance to them. I have been to many archives around the world, and my experience at Hoover was thoroughly pleasant and useful. I urge other Africanist scholars to take advantage of the rich research material at the Hoover archive.