Hoover’s documentation on Ignacy Paderewski and the restoration of Poland after World War I has expanded substantially during the past several years, first with the acquisition of the papers of Ernest Schelling, Paderewski’s American student and friend, which included the memoirs of Helena Paderewska, and now with the arrival of the archives of Zygmunt Iwanowski (1874–1944), another of the prime minister’s close associates and supporters.

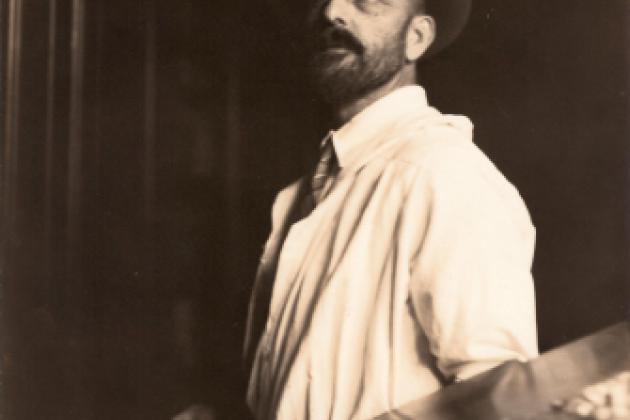

Iwanowski was born in Odessa into an artistically talented Polish aristocratic family. His three sisters were accomplished musicians, and young Zygmunt was a talented painter. He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg, graduating with a gold medal and an offer to paint the Russian royal family of Nicholas II, an honor he did not pursue. He left Russia soon after graduation, continuing his studies in Warsaw, Munich, Paris, and London, where he married Helen Moser, an aspiring American singer. In 1903 they moved to the United States, where Iwanowski established a studio in Westfield, New Jersey. He soon became recognized as an outstanding illustrator for such popular periodicals as Harper’s, Scribner’s, Ladies Home Journal, and Century. He also painted portraits, most frequently of his wife, Helen, but his likeness of President Theodore Roosevelt, now in the National Gallery in Washington, is probably his most famous. He signed his works Sigismund de Ivanowski and under that name he has a place in the history of American painting.

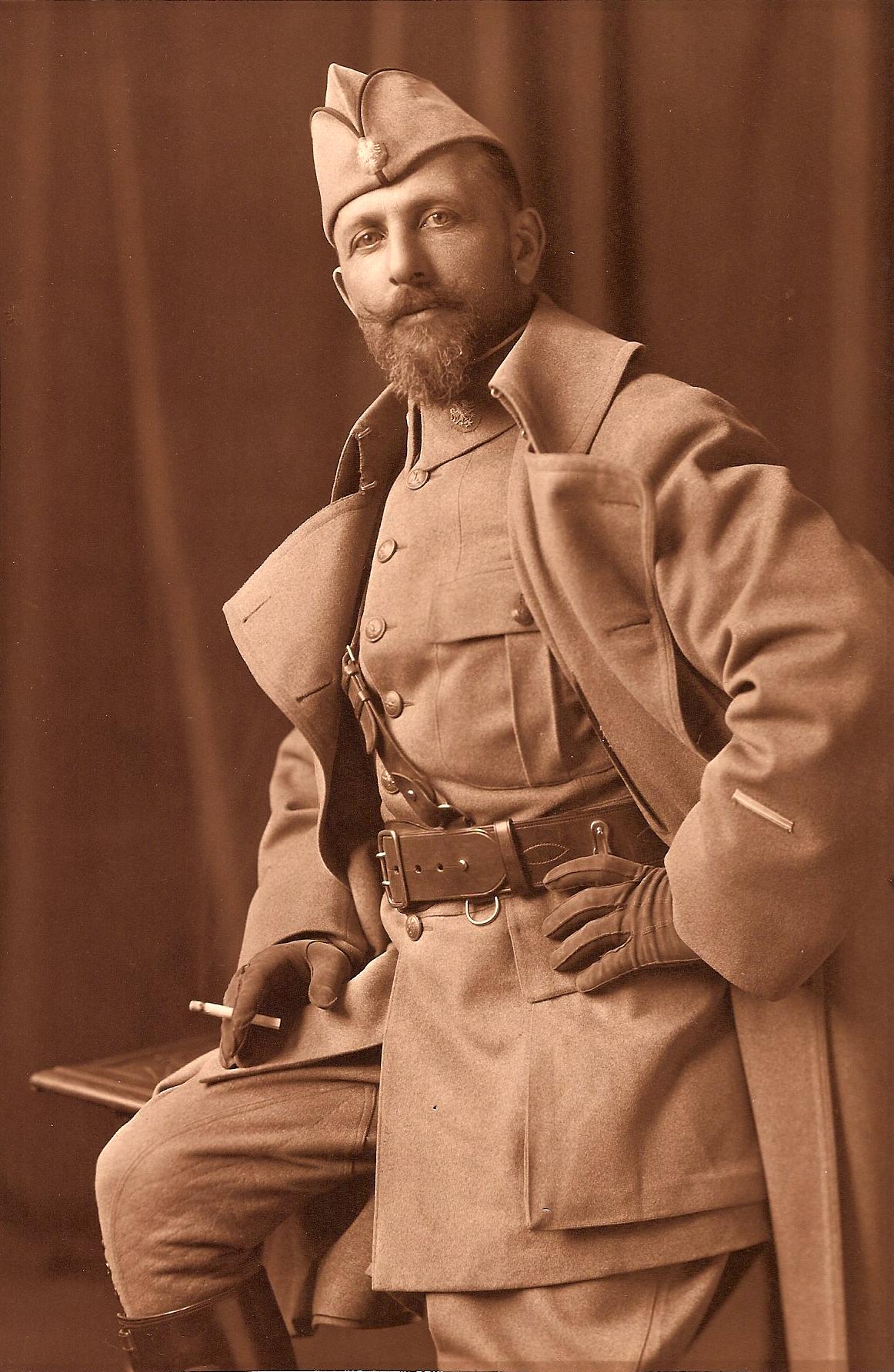

Iwanowski had been a fan of Paderewski’s music for more than twenty years; in 1917 he met the Polish virtuoso and political leader in person in Washington, DC, and there became Paderewski’s inseparable companion and trusted adviser. Iwanowski closed his Westfield studio and donned the French-style light-blue uniform of the newly formed Blue Army, a volunteer Polish force of some twenty-five thousand men recruited in the United States and equipped and trained by the French and the British in camps in Canada. The Blue Army was sent to France, where it fought with distinction against the Germans. A Polish intellectual, a fellow artist, fluent in French and English, Iwanowski was ideally suited to be Paderewski’s attaché, responsible for the recruitment effort and liaison with the Allies. Zygmunt Iwanowski was honored by the French government with the Legion of Honor for his work of organizing the Blue Army.

After the November 1918 armistice, Zygmunt and Helen Iwanowski joined Ignacy and Helena Paderewski in their triumphant return to Poland. In Warsaw, Iwanowski continued his work as military aide to Paderewski, accompanying him during all his domestic and foreign trips, including those to the peace conferences of 1919. Helen, having learned Polish, assisted Madame Paderewska with her numerous social and charitable establishments and organizations. The Iwanowskis returned to the United States several years later, broke but satisfied with the work they had done in Poland, and returned to their quiet artistic life in Westfield, New Jersey.

The Iwanowski Papers include personal correspondence, most notably with Ignacy and Helena Paderewski, documentation on the political and economic situation in Poland immediately after World War I, and materials on Iwanowski’s artistic career.

The acquisition of the collection is an interesting story in itself and testimony to the complexities of archival collecting and the wide reach of the Hoover Institution. Research indicated that Iwanowski’s only child, Irena, died in 1979 and that his grandson, David Perry, died in 2000 while teaching English literature at Wuhan University in China. Perry never married and had no children. The trail seemed to have reached a dead end, until a call from Poland, followed by several calls within the United States, confirmed that there indeed was an Iwanowski archive and that it was held by a musician, first violin at the Phoenix Symphony, who happened to be a former student and protégé of Iwanowski’s grandson. Curator Maciej Siekierski’s visit to Arizona to meet with the Chinese American violinist convinced him to donate the Iwanowski papers to Hoover.

For additional information, contact Maciej Siekierski at siekierski@stanford.edu.