By Simon Ertz, Hoover Centennial Librarian for Collection Analysis

As our users know, there is no end to the discoveries one can make in the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. The find our librarians made in fall 2021, however, was extraordinary even by our standards. A review of materials kept in our vault area brought to light a massive folio, its time-worn, nondescript cover displaying neither author, nor title, nor call number. A closer inspection revealed this weighty volume, which had been resting inconspicuously on the shelf, to be the oldest book in our library collection: a German edition of the Old and the New Testament of the Bible, translated by Martin Luther, printed in Frankfurt, Germany, in the year 1563.

How did a 16th century Luther Bible find its way into Hoover’s library stacks? So far, there are only educated guesses. While Herbert and Lou Henry Hoover nurtured a life-long passion for acquiring antiquarian books, their main interest in this area were titles on geology, metallurgy, and science. Since the Luther Bible was evidently never incorporated into the Hoovers’ personal collection of rare books (which was ultimately donated to the Claremont Colleges Library), since it was never cataloged by Hoover librarians either, and since no paper trail of its acquisition has been found, it is conceivable that it was not deliberately purchased or officially gifted. Potentially, it came to Hoover in a more fortuitous manner—perhaps as bycatch of a collection trip to occupied Germany after World War II. Possibly, further research will shed more light on its provenance.

Much easier to answer is the question of the book’s historical significance. Martin Luther’s translation of the full text of the Bible into German was a seminal event in the history of the Reformation, and in German history more broadly. True, more than a dozen German Bible translations had already appeared by the mid-15th century, in response to the slowly growing literacy of urban populations—and despite efforts of Catholic clergy to discourage lay people from individual Bible study. None of these earlier translations, however, came close in significance and impact to the one on which Martin Luther began to work right after his excommunication by Pope Leo X in January 1521.

As a church reformer, Luther’s single most important principle was that the answers to all fundamental questions of human existence lay in the biblical text itself, rather than in rules imposed by the institutionalized church and doctrines dictated by the papacy. Hence his determination to make the scripture directly accessible to believers—and to guide and direct them in its study to help them achieve a proper understanding.

When translating the books of the Old Testament from the Hebrew, Luther collaborated with several Hebraists from Wittenberg, where he had taken refuge under the protection of Frederick III, Elector of Saxony. Luther added introductions, explanations, and numerous short commentaries (glosses) in the margins. Even more groundbreaking was his translation of the New Testament, which, to him, contained the core of the divine message: that salvation was attainable through faith in God’s grace alone. Here, Luther relied on the Vulgate, the Latin Bible commonly used since the Middle Ages, as others had done before him. But unlike previous translators, who had often reproduced the chapter and even sentence structure of the Latin text, Luther rearranged its parts, aligned them with his doctrine, and, most importantly, wrote in a direct and accessible vernacular meant to appeal to all contemporary German speakers.

Luther’s first complete Bible translation appeared in print in 1534. By the time of his death twelve years later, more than 200,000 copies of hundreds of editions had entered circulation—a sensational publishing success that helped spread Luther’s teachings far and wide.

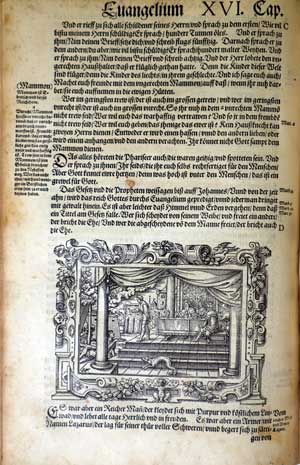

Despite this proliferation of Luther Bibles, Hoover's copy was still remarkable at the time for its impressive execution, especially for its numerous fine illustrations. First printed in 1560 by David Zöpfel, Johann Rasch, and Sigmund Feierabend in Frankfurt, the edition was adorned with 151 woodprints from the workshop of Virgil Solis (1514–1562), a prolific printmaker and book illustrator based in Nuremberg, who often adopted motifs from famous German and Italian masters. The Solis Bible woodprints were clearly a success at the time: not only were they simultaneously published in a separate volume in the style of the biblia pauperum (“Bibles for the poor”), a genre that combined pictures of biblical stories with a minimum of text to convey religious messages to the less literate; copies were also used to illustrate several other Bibles published in subsequent years in Cologne, the Netherlands, and even England. Undoubtedly, these attractive images amplified the effect of Luther’s accessible vernacular, annotations, and explanations in making this edition appeal to contemporary audiences.

In mid-16th Germany, Luther Bibles were not quite cheap, and a copy of the quality of the Frankfurt folio Bible would likely have been owned by a church or other institution. Indeed, its format would have made it ideally suited for use as a lectern Bible. While we don’t know where and how exactly Hoover’s copy was used, the centuries have not left the book unscathed. Unfortunately, several dozen pages have been lost, most significantly the first 24 leaves (48 pages), including the main title page, frontispieces, the foreword and register for the first part, and the first 6 leaves of the Book of Genesis. A number of interior pages are missing as well, and a few pages were partially damaged. While some of the lost pages contained illustrations, the losses were most likely caused by external damage, and the large majority of woodcuts is still present. Presumably in the early 20th century, the book was repaired and rebound in a robust, if somewhat primitive manner. Fortunately, a complete copy of this exact 1563 Bible has been digitized by the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin and can be browsed online, including the pages that are missing from Hoover’s copy.

Regardless of how it may have come to Hoover, one might wonder how a 16th century Bible relates to a library collection that documents “War, Revolution, and Peace” in (mostly) the 20th century. While the chronological distance is indisputable, certain parallels and connections can be drawn nonetheless. To begin with, Hoover’s archival and library collections contain a welter of materials reflecting different ideas and ideologies. More specifically, sources on the activities of religious and missionary groups and organizations are present in our collections as well. The prominence in the collection of the themes of modern German history, including the history of German nationalism, provides another link. To be sure, Luther was no modern-era nationalist. Unlike Calvinists or Puritans, he always separated religion and politics, and he never promoted the idea of an exclusive, confessionally defined nation. Still, Luther did set out to reform primarily German Christendom, and he saw and deliberately used the German language as an instrument to unite the German people for this purpose. Indeed, his Bible translation “significantly contributed to the reduction of the Babel of German dialects” (Caspar Hirschi)—and thus to the formation of a linguistic German nation. Furthermore, the Hoover 1563 Bible’s use of word and images to further its message aligns with our abundant modern print publications that likewise combined rhetoric and visual language to maximize their reach in their times. Finally, there is the simple fact that the extraordinary success of the Luther Bible fueled the rise of Protestantism as a major cultural and political force in Germany and beyond, a development with far-reaching historical consequences extending well into the 20th century.

Now that it has resurfaced, our 1563 Biblia, das ist: die gantze Heylige Schrifft (Biblia, That Is: The Entire Holy Scripture), has finally been properly cataloged. While Stanford University Libraries have several historical Luther Bibles in their collections—one from the 17th and six from the 18th century—as well as facsimile editions of the 1545 edition, the Hoover Institution Library & Archives' copy is currently the only original edition of a 16th century Luther Bible available on the Stanford campus. Users who would like to experience this remarkable book in person are welcome to do so, after scheduling an appointment, in our Library & Archives Reading Room.

(All images from the Hoover Institution Library & Archives)

Image Captions:

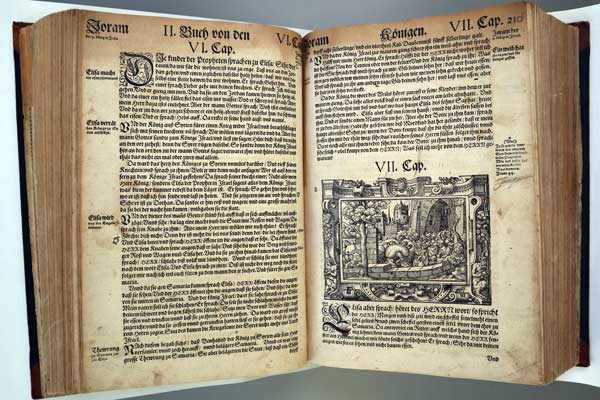

- The Bible, opened. On display is the Second Book of Kings, Chapter 6 and beginning of Chapter 7, with a woodcut illustration. The main text’s single-column layout, already chosen for the first 1534 edition, enabled Luther to add keywords for better orientation and glosses for better understanding in one margin, cross-references to other books and verses in the other margin.

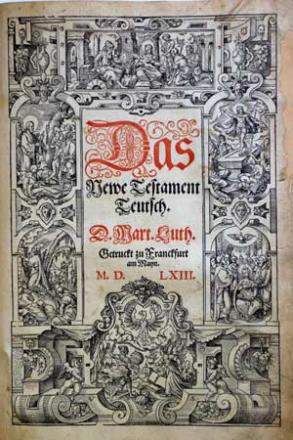

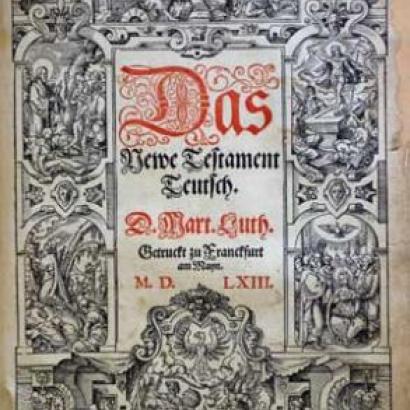

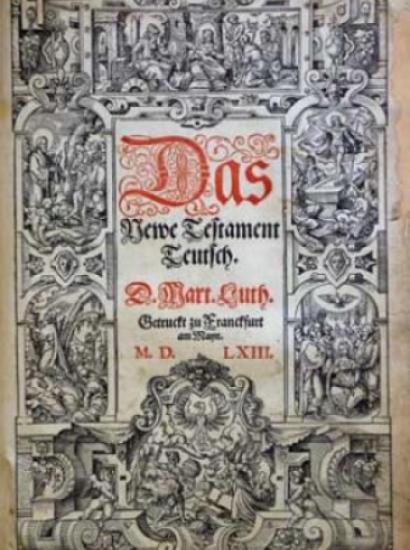

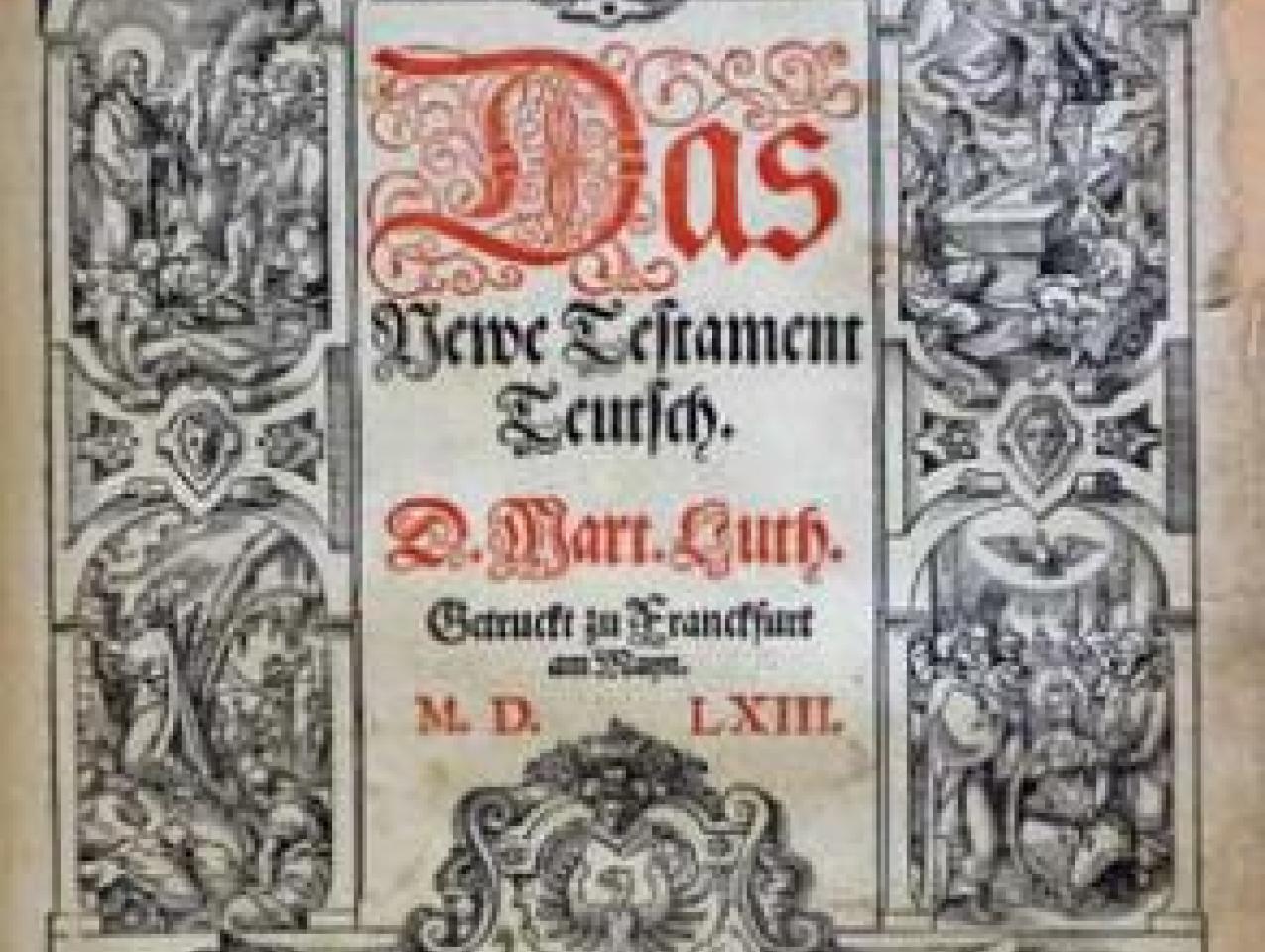

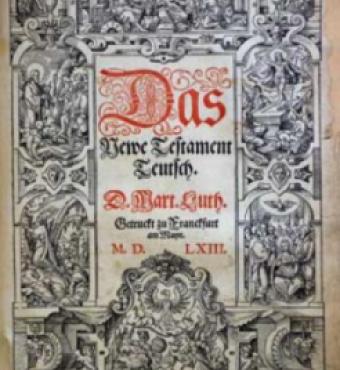

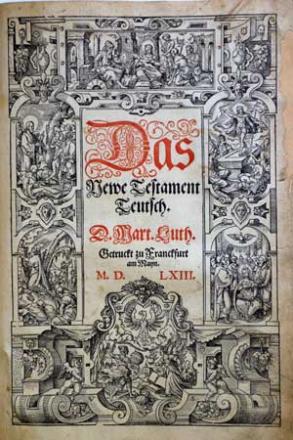

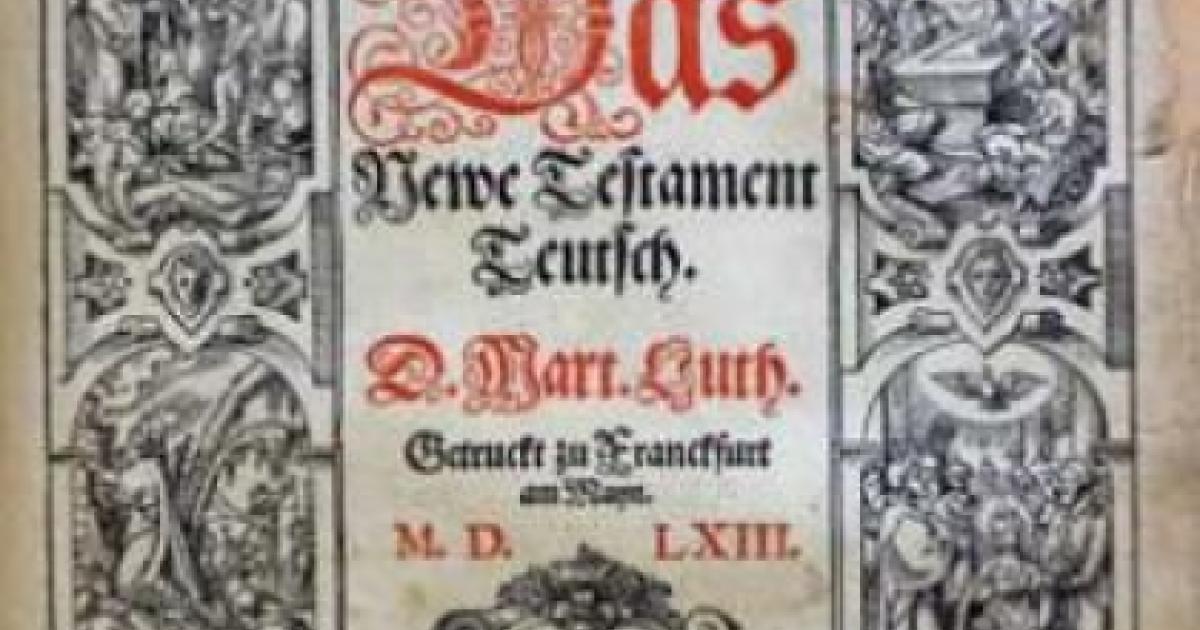

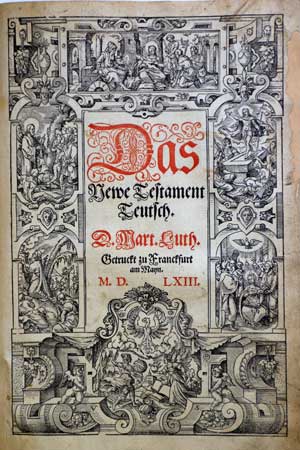

- Title page of the New Testament, the volume’s third part. While the title pages for parts one and two are missing from Hoover’s copy, the title page for the third part is present, which helped to quickly identify the edition. The inscription, translated: “The New Testament. German. D[r.] Mart[in] Luth[er]. Printed at Frankfurt, Main. MDLXIII. Note, at the bottom of the ornate frame, the initials “V” and “S” for the workshop of “Virgil Solis,” printmaker.

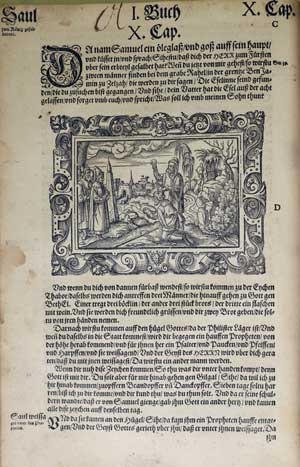

- Book 1 of Samuel, Chapter 10, with woodcut: Saul is anointed king. On the top of the page, an unknown user has left a handwritten marking in ink.

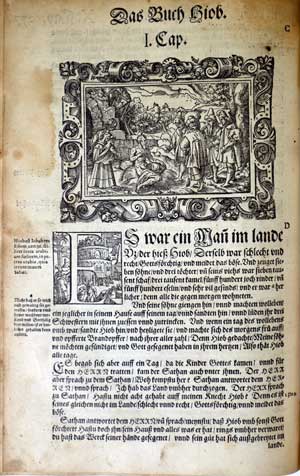

- Beginning of the Book of Job with an ornate initial and a woodcut illustration displaying Job, his body afflicted with boils, in conversation with his friends. On the margin, one of Luther’s many explanatory glosses for his readers: “It was not for his wealth and earthly power, but for his wisdom, reason, and faithfulness that [Job] was deemed more glorious than others.”

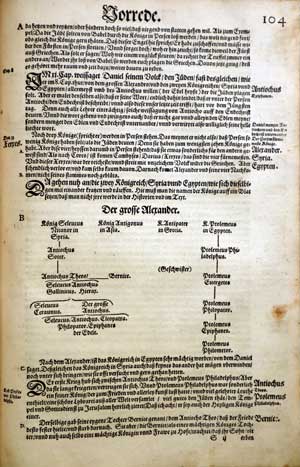

- A page from Luther’s preface to the Book of Daniel, in which he provides background information on the struggles between the kingdoms of the Diadochi, aided by a schematic genealogy of the various rulers that followed Alexander the Great: “Here, one has to put down the names of the kings on a sheet [of paper] so as not to get confused in the story and the text.”

- Gospel of Luke, Chapter 16: A page with a woodcut illustrating the story of Lazarus, who can be seen begging to be fed crumbs from the rich man’s table. In the margin, another one of Luther’s glosses. Here, he explains the meaning of “Mammon” (“Mammon is Hebrew and means wealth”), of what it means to use “mammon” in an unethical manner, and of what spiritual consequences this has.