“Wonderful things”

As Sir Flinders Petrie gazed in dumbfounded silence into Tutankhamun’s tomb with the light of a single candle, his colleague asked, “What do you see?”

“Wonderful things,” he responded.

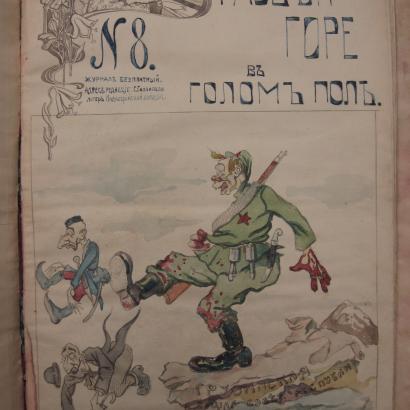

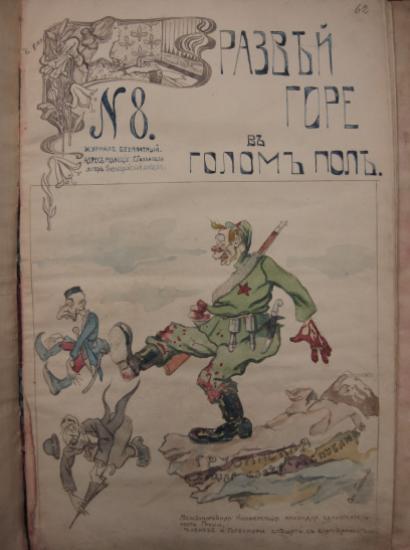

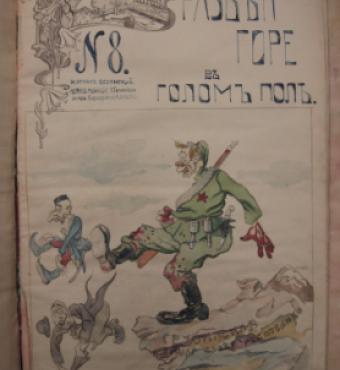

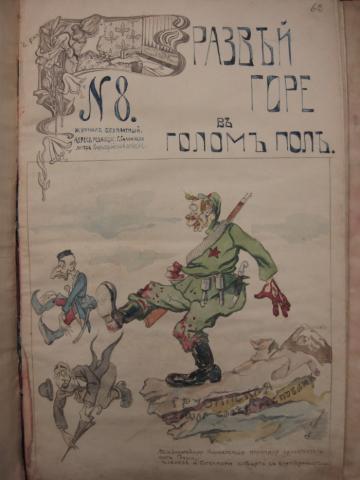

As curator, I have seen some spectacular collections come into the Hoover Archives. But only Petrie’s words could relay my feelings when I opened a newly delivered box that had arrived in the mail containing the slender bound volume containing several issues of Razviei gore v golom polie. Handwritten periodicals, each issue of which was produced in single copy for circulation among the officers and soldiers of General Petr Vrangel’s army, interned on the Gallipoli Peninsula in 1920–21, have been known to historians for some time. But this knowledge came to us from memoirs and contemporary accounts of life in the camp; very few issues had actually survived. So receiving this set of issues of Razviei gore v golom polie was indeed the equivalent of discovering a treasure that had been thought to have been lost to history and scholarship forever. The drawings, caricatures, poems, political satire, and other materials in this journal are bound to thrill researchers for many years to come. The content is varied, from short stories to historical sketches and analyses of current events, as well as humorous sketches of daily life in the camp and some of its more colorful personalities. The name of the journal is itself a pun. “Gallipoli” to the Russian ear sounds a bit like “goloe polie” or “empty field,” which is exactly what it looked like to the units of the White Army interned there. The title as a whole could be translated as “Lose Your Grief in an Open Field” referring to the lighthearted nature of the journal.

Razviei gore v golom polie is a gem for historians, literary scholars, and anyone interested in what happened to those Russians forced to leave their country after the Bolsheviks came to power in Russia. The item has been catalogued as an increment of the Vrangel’ collection.

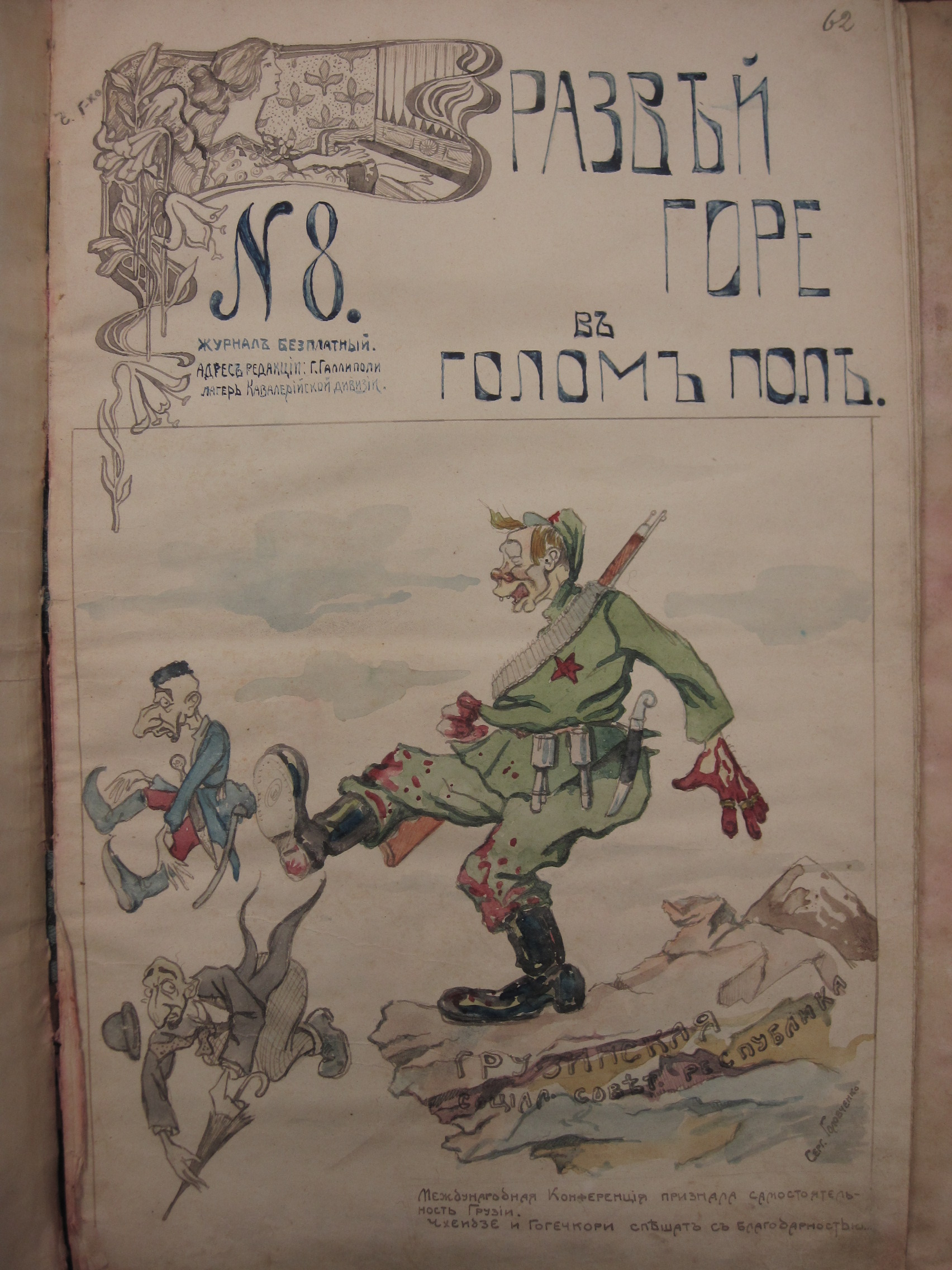

The caption to the illustration reads: “The international community has recognized the independence of Georgia. Chkheidze and Gegechkori are hurrying to Europe to express their gratitude.” Of course, Georgian president Nikolai Chkheidze and foreign minister Evgenii Gegechkori were not so much hurrying to express their thanks as heading into exile, for with the country having been overrun, as the illustration shows, by the Red Army, Georgia’s independence was short lived. The reason for the bitterness of the satire is that the independent Georgian government had exhibited great antipathy toward the White Army (which, in fact, had stood between the Georgians and the Bolsheviks for several years, though the Georgian socialist ministers felt that the Bolsheviks were the lesser evil), and the latter’s “we told you so” is palpably visible in the cartoon.

Anatol Shmelev PhD

Anatol Shmelev is a research fellow, Robert Conquest curator of the Russia and Eurasia Collection, and the project archivist for the Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Collection, all at the Hoover Institution.