The Hoover History Lab and The Hoover Institution Library & Archives invite you to The Party's Interests Come First: The Life of Xi Zhongxun, Father of Xi Jinping, a book talk with the author, Joseph Torigian on Tuesday, June 3, 2025 from 4:00 - 6:00 pm PT in the Shultz Auditorium, George P. Shultz Building.

China's leader, Xi Jinping, is one of the most powerful individuals in the world―and one of the least understood. Much can be learned, however, about both Xi Jinping and the nature of the party he leads from the memory and legacy of his father, the revolutionary Xi Zhongxun (1913–2002). The elder Xi served the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) for more than seven decades. He worked at the right hand of prominent leaders Zhou Enlai and Hu Yaobang. He helped build the Communist base area that saved Mao Zedong in 1935, and he initiated the Special Economic Zones that launched China into the reform era after Mao's death. He led the Party's United Front efforts toward Tibetans, Uyghurs, and Taiwanese. And though in 1989 he initially sought to avoid violence, he ultimately supported the Party's crackdown on the

Tiananmen protesters.

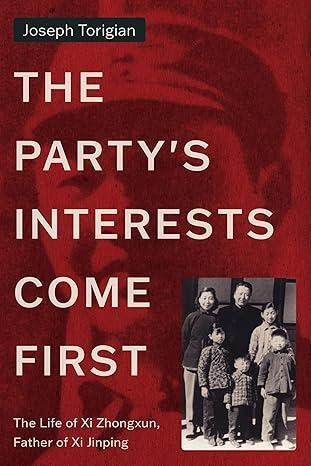

The Party's Interests Come First is the first biography of Xi Zhongxun written in English. This biography is at once a sweeping story of the Chinese revolution and the first several decades of the People's Republic of China and a deeply personal story about making sense of one's own identity within a larger political context. Drawing on an array of new documents, interviews, diaries, and periodicals, Joseph Torigian vividly tells the life story of Xi Zhongxun, a man who spent his entire life struggling to balance his own feelings with the Party's demands. Through the eyes of Xi Jinping's father, Torigian reveals the extraordinary organizational, ideological, and coercive power of the CCP―and the terrible cost in human suffering that comes with it.

>> Eric Wakin: Thank you for coming. I'm Eric Waken. I'm the Deputy Director of the Hoover Institution and the Everett and Jane Hauck Director of our library and Archives. It's my great pleasure to welcome you here today to a conversation between Joseph Torigian and Stephen Kotkin about Joseph's amazing new book, The Party's Interests Come First, the life of Xi Zhongxun, father of Xi Jinping.

I'll have more to say about two scholars in a moment. Just let me say a couple of introductory remarks and thank you. So I wanna thank our director, Condoleezza Rice, for her support of the Hoover History Lab, run by Stephen Kotkin, and of our library and archives and also our overseers, our donors, who support everything we do at Hoover.

We are almost entirely privately funded, so everything we do is through the generosity of our supporters. Also want to thank Steve, Joe Ledford, Cheryl Steets, other members of the History Lab, and my colleagues at the library and archives and on the Hoover Events and Planning team for making this possible.

We're here at the Hoover Institution because of the vision of one man, that's Herbert Hoover. I always like to say a minute or two about him, if you'll indulge me. He endowed what was in 1919, the Hoover War Library with a $50,000 gift and a telegram to collect material on war.

$50,000 then in purchasing power, now is roughly $900,000. That was his deed of gift, the telegram. 15 years before the National Archives was founded, the Hoover War Library, which became the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace, now was founded. And it's through his generosity and all the other people that followed him with the idea that collecting material on war, revolution and peace and studying them, as Joseph has done and Steve has done and many other scholars in this room has done, is the mission of this institution.

Since Mr. Hoover's donation, we've become the largest private organization dedicated to documenting, studying, discussing war, revolution, peace in the 20th and 21st centuries. We're a research center dedicated to ideas defining a free society, supporting hundreds of resident and visiting fellows, and we have the best library and archives in the country, I would argue.

Mr. Hoover said this about our mission, the institution must dynamically point the road to peace, to personal freedom and to the safeguards of the American system. And about the library, its purpose is to build up a great research institution upon the most vital of all human questions, war, revolution and peace.

I think we honor Mr. Hoover in continuing the programming that this represents. By the way, in the corner in a exhibition vitrine there, there's three items Joseph asked us to put out there. Two are diaries from Li Ray, who Joseph will refer to. Joseph will refer to him in a moment.

The other is a blanket that was given to the Dixie mission in the 1940s in a province in which Xi Jinping's father was head of the province at the time. So it's possible that this was given to the Dixie Mission by Xi Jinping's father, but Joe's going to say more about that now.

Let me introduce our scholars and then we'll get moving. Steve Kotkin is the Kleinhein Senior Fellow and founder and director of the Hoover History Lab, which functions as a hub for research, teaching and convening in the classroom and in print. The lab studies and uses history to inform public policy, develops next generation scholars, and reinforces the work of Hoover's world class historians to inform scholarship and teaching of history at Stanford and beyond.

Steve's research, as you probably all know, encompasses geopolitics and authoritarian regimes. His publications include two volumes of a magisterial three volume biography of Joseph Stalin, which is as much about Russia's power in the world as it is about Stalin's power in Russia. He's also the author of many other books analyzing the demise of Communism, which unfortunately, like Yul Brenner and Westworld, never seems to stay dead.

Steve is also hosted the National Intelligence Council at Hoover and is a consultant in geopolitics. Finally, he's the most prolific user of our library and archives, perhaps. Joe Turigian is a research fellow at the Hoover Institution and an associate professor at the School of International Service at American University in Washington.

A Center Associate of the Lieberthal Rogel center for Chinese Studies at Michigan, and he's been a visiting fellow in many places, including the China in the World program at Australian National University. A Stanton Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, a postdoctoral fellow at Princeton's Harvard China and the World Program, and has had many other appointments.

His first book was Prestige, Manipulation and Elite Power Struggles in the Soviet Union and China after Stalin and Mao. Today's talk, though is based on his recent book, which is in front of Joe and everyone else. The Party's interests come first. Joseph is also a prodigious researcher in our and other archives, as well as a scholar who has directed significant collections to Hoover.

We're very grateful for both Steve and Joseph, not for just their scholarship, but for the way they care about the archives and perpetuate it for future generations by directing donors to give their collections to Hoover. I've pulled a couple items, as I mentioned, from the event. They're displayed here right now.

Please give a warm Hoover welcome to Stephen Cochin and Joseph Turigian.

>> Stephen Kotkin: Thank you, Eric. It's great to see everybody. It's fantastic to partner again with the library and archives for a special treat. A breakthrough book. The research is prodigious. The sensitivity and understanding of the communist phenomenon.

The biographical analysis of the lives in question. Just phenomenal work. Joseph has already authored one of the great books on succession politics for any authoritarian regimes. But certainly for the specificity of the communist cases. But both the Soviet Union and China, with massive original research in both cases.

I can't recommend that first book of his more highly, it really is fantastic. Today, even better, the biography masterpiece which you're looking at over here is so richly researched. During the copy editing, which is always a long and involved process, more and more documentation was coming forward. This is about a person that the Communist Party regime still in power in Beijing doesn't want you to know the full truth.

It wants you to know a certain version of the person's life, and a certain version, of course, of his son's life. Not the version that Joseph, through this prodigious research in so many different places, unexpected places, has found original material, sometimes used by others, but not always. And never used in such a great collective enterprise like he's done.

The book is for sale outside, and Joseph will be signing copies of the book for those of you who are moved to read it. It really does repay the kind of reading sweeps you in and keeps you there all the way through to the end. We'll also have a reception afterwards in addition to the book signing.

I should say that we had a book talk not that long ago in this very room by a person, Benjamin Nathans, also a prodigious user of the Hoover Library and Archives. And he was a winner of the Pulitzer Prize this particular year for his book on dissent in the Soviet Union.

So let's just say we've set a high bar, but also a precedent. And please join me, Joseph Torigian, biographer and historian and political scientist.

>> Joseph Torigian: Well, thank you, Steve, for that very generous introduction. It really is an honor to speak to you today, which is the official book launch day at the Hoover, because if it wasn't for the collection here, this book would have been entirely impossible.

So it's deeply meaningful that I can speak to you literally feet away from the collection that made my book the book that it is. And so I'm here today to give a talk about Xi Zhongxun, not only the father of Xi Jinping, but a major figure in the revolution and a leading individual in the People's Republic of China after it was established in 1949.

So, naturally, I'm going to begin my remarks today in Iowa, specifically one of the premier tourist attractions of central eastern Iowa, a German heritage site known for beer and crafts, the Amana Colonies. And I'm not just saying that because the Amana Colonies are a few miles from the birthplace of Herbert Hoover, and I want Herbert Hoover people to buy my book, although books are on sale right outside.

But this was an interesting trip for Xi Zhongxun to go to the United States in 1980 to the Amana Colonies at 67 years old. This was a historic trip of Chinese governors to the United States. Xi Zhongxun at the time was the party boss of Guangdong Province, which was at the very forefront of China's opening to the west.

While Xi Zhongxun was leader there, the first consulate in China was established in Guangzhou, the capital of Guangdong. And Xi Zhongxun is instrumental in the creation of the Special Economic Zones, the most famous physical manifestation of China's new interactions with the outside world. The Americans who organized this trip for Xi Zhongxun that I talked to, described him as someone who was friendly, charismatic, the kind of person who would make sure that the translator had a glass of water, but that often he would go quiet, as if he had something on his mind.

And he could come across occasionally as reserved and distant. But all that changed when Xi Zhongxun visited the Amana Colonies. According to one individual who was present, Xi was enthralled. He became a different guy and was almost crawling across the table. Now, I don't think that Xi Zhongxun was this excited because he loved the beer in the Amana colonies.

Even though I've been there and the beer is quite good, I think she had such an emotional reaction because he was listening to a tour guide tell a story about how a community built on collective and utopian principles had decided, 88 years after it had founded, to disband.

It was a story, in other words, about how a communist society had become a tourist destination, why? Because the old charismatic leaders had died and their successors did not command total obedience. A system of bureaucracy and privilege had emerged. The collective organization of agriculture had proved inefficient. But most importantly, the younger generation, inspired by the outside world, wanted a more materialist, consumerist lifestyle.

So let's reflect for a moment about what kind of person with hearing this explanation of the Amana Colonies from the tour guide. This was someone who had experienced extraordinary suffering for the sake of the cause. He was arrested at 15 years old and joined the party in jail.

He nearly died fighting the Nationalists on several occasions. Before the revolution was complete on one occasion, he was arrested by other Communists and thought he was going to die. He claimed that he was going to be buried alive. And for years after, he would show the physical wounds to other people to show what he had gone through.

But the suffering didn't end. After the People's Republic was established in 1962, he was purged from the leadership and subjected to 16 years of exile, incarceration, and humiliation. One of his daughters committed suicide during the Cultural Revolution. Now, in 1980, Xi and his comrades were facing the question of whether what they had built with all of these sacrifices would endure.

And for many reasons, it didn't look good, especially from Xi's position as governor of Guangdong, why? Tens and tens of thousands of people were fleeing from communist China to capitalist Hong Kong, which bordered on Guangdong, many dying in the process. Fears of Western ideological infiltration were especially prominent in Guangdong, given its proximity to Hong Kong.

And young people who didn't think the party was moving fast enough to overcome the tragic legacies of the Cultural Revolution were taking to the streets of Guangzhou. Crime rates were exploding, especially smuggling with Hong Kong. And it was unclear whether more rule of law or a more forceful response was the right answer.

In other border regions hundreds of miles away, Beijing was shocked when representatives of the Dalai Lama were met with enthusiasm by Tibetans, not the hate that the Communist Party expected. And more and more protests were erupting in Xinjiang. Abroad, the Solidarity protests in Poland were raising questions about the Communist project globally.

And even though Mao had taught the party lessons about the dangers of strongman rule, as Xi was listening to the Amana Colony's tour guide, the autocratic Deng Xiaoping was finishing his defeat of Mao's initial successor, the more consensus oriented Hua Guofeng. There's many ways to try to tie the threads of a man's life together for a book talk, but for the reasons I've begun to illustrate with this anecdote from Iowa, today I'm going to talk about the question of Xi Zhongxun and political order.

How a man who suffered so much for a political party thought about how to make it survive while he was alive, but also decades into the future. And of course, this has special relevance for the real reason I know you're all here, which is to learn about Xi Jinping, the son of Xi Zhongxun and the current leader of the People's Republic of China.

I'll proceed by addressing five themes. Ideology, communism as a global phenomenon, Beijing's relationship with ethnic minorities in the borderlands, succession politics, and conclude with perhaps the most existential question, how to win over young people to the revolutionary project. But I'm gonna begin with ideology, because it's only with the sensitivity to the peculiarities of the Bolshevik worldview that everything else that I say today will make sense.

And it speaks to the question of political order, because ideology is how the party justifies itself and explains why it deserves so much devotion. And that's ironic for one reason, which is that when Xi Zhongxun was a young boy, he was not really attracted to the party because he was reading Das Kapital.

But he was born into a milieu of radicalism, he was born in Shanxi Province, where Qin Shi Huang had forged the first unified state and emperors had ruled for millennia from nearby Xi' An. By the time Xi Zhongxun was born in 1913, two years after the Qing Dynasty was overthrown, the area had been rocked by decades of war, hunger, and banditry.

It was a place of contradiction that led one of Xi's close childhood friends to later say that, quote, the region made people develop an extreme way of thinking. On the one hand, it has a rich cultural legacy but on the other hand, the people face a difficult situation and the chaos of war never ends.

>> Joseph Torigian: Xi, as he was starting to learn about the revolution, didn't really understand exactly what it was that Communism was all about. In fact, he was quite frank about this. Decades later, he wrote, at the time, the revolutionary situation allowed all kinds of revolutionary books and newspapers for reading.

But regrettably, because my individual study was too poor, even if I read more, that just meant that there was more that I did not understand. Because I was too young, my memory only allowed for half-baked knowledge, and my understanding of communism was still not deep. Now, why was he able to read this communist literature?

Well, when he was a very young person, the Chinese Communist Party was still in an alliance with the Nationalists, known as the First United Front. But it was in April of 1927 that Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of the Nationalists, betrayed the Communists and massacred them across the entire nation.

And so, over the course of 1927, in Xi's home province, there is a brutal crackdown on the Communists. There are two insurrections that end in failure. The schools are targeted, students are getting arrested, sometimes killed. So by the spring of 1928, a Communist Party cater tells Xi Zhongxun, then 15 years old, along with two other young boys, to attempt to poison an academic administrator at their middle school.

They fail. Several teachers are poisoned. They're arrested, put in jail, and Xi Zhongxun joins the Communist Party while in prison. And the person who formally introduced him into the party shortly after he was released from jail, committed suicide in Shanghai, apparently having suffered a mental breakdown. When Xi Zhongxun is released from jail, he's covered in eczema and boils.

He can't walk. His father dies soon after, apparently related to the mental stress of his son having been incarcerated. His mother also dies just a few months later. Two sisters are also lost, likely somehow related to the ongoing famine. He can't find the party. He's facing desperation. He's a hunted man.

He can't go back to school. And how does he re-energize himself? How does he inspire himself? It's not by reading Marx, it's by reading a novel, a novel written by now a somewhat obscure Chinese novel author whose name is Zhang Guang Zhi, who wrote a book called The Young Wanderer.

Now, this is a very interesting moment because it shows the power of a cultural product to inspire. Now, this is not a high quality book. I think we have Chinese cultural experts in the room. They certainly know the famous scholar of Chinese literature, Tie Xiao. Well, he wrote about Zhang Guang Zhi and his readers.

Xiao wrote that Zhang Guang Zhi no doubt had his fans among the barely illiterate youths who did not care so much about the quality of the writing as the emotions he so frankly expressed. Did not Zhang's popularity in his lifetime constitute rather an unfavorable comment on the intellect of the readers of those days, who seemed merely excitable in temper and indiscriminate in taste?

So Tie Xiao writing about Xi Jinping's father without realizing he was writing about Xi Jinping's father. But what is this book about? It is a relentlessly bleak novel about a young person who just goes from one disaster to another. A character who writes that the more pain that evil society brought me, the more powerfully did my resistance develop.

And Xi Zhongxun, by the way, would tell his son that when he faced doubts, when he was scared and frightened, this was the novel that he read. So ideology can inspire, but it can also be very dangerous because in 1935, 7 years after Xi Zhongxun joins the party, he's arrested by members of his own party.

Well, why is he arrested? Well, Xi Zhongxun, he's from the region. He's fighting a revolution that tries to do justice to the local characteristics of society without being too ambitious, too aggressive, and getting themselves killed. But these younger people who come with books that were given to them by Moscow, say to Xi Zhongxun that because he's not being radical enough, that it's a manifestation of an ideological problem.

And so Xi Zhongxun is thrown in jail. So it shows how differences of tactics can suddenly turn into something more dangerous because of this ideological charge. 1952, 3 years after the regime is established, Xi Zhongxun is brought from the northwest to Beijing to become the minister of propaganda.

Meaning his job is how to explain to an entire country of people why they should believe in communism and dedicate their lives to building socialism. Ten years later exactly, Xi Zhongxun is purged from the leadership because of a novel. In 1962, Mao Zedong, worried that the party was losing its revolutionary élan, became preoccupied with the question of class struggle.

And he interpreted Xi Zhongxun's role in the creation of this novel as a manifestation of an ideological problem, and Xi Zhongxun spent, as I said, 16 years in the political wilderness because of it. Xi Zhongxun is rehabilitated. In 1978, he goes to Guangdong. Everyone knows that the cultural revolution is a disaster.

But nobody is quite sure how to justify moving in a new direction without raising so many doubts in the entire project that the whole house of cards comes down with them. So famously in 1978, the 3rd plenum, economic modernization, is now the key link, not class struggle anymore, formally.

But just a few months later, the rising paramount leader Deng Xiaoping gives a speech in which he introduces a very conservative formulation known as the Four Cardinal Principles. And all of these pro-reform people in the party saw that and said, wait a second, are we going in a new direction or not?

We're not really clear anymore. And so it leads to this contradiction between the three and the four. The three meaning the third plenum, economic modernization, and the Four Cardinal Principles, meaning ideological orthodoxy. Now, a lot of people were disappointed in Deng because of the Four Cardinal Principles, but not Xi Zhongxun.

Xi Zhongxun says at the time that only with the Four Cardinal Principles can thought be liberated in a way that is right and not wrong, effective and not formulaic. So what's interesting is he's saying we can't get the change right if we don't also continue to talk in these more conservative terms.

Now, in Guangdong, where Xi Zhongxun is the party leader, people don't understand how to think about this debate. Some people think that reform had already gone too far, that they were liberating thought all the way to Japan and the United States. States, other people thought that these ideological debates were totally meaningless and could be ignored.

Other people thought that, yet another power struggle. We're just coming out of the Cultural Revolution. Are we doing this all over again?

>> Joseph Torigian: And Xi Zhongshun says at the time that we can't move in this new direction without forgetting that we need both a material civilization and a spiritual civilization, which is kind of a remarkable thing for a Marxist to say, a materialist.

So he's saying people need to be committed to the cause but Xi Jiangxun also at this time, can't say what communism really is. He says in 1980 that China has already done socialism for 32 years, but we are still groping for just exactly what kind of road we will take.

The groping might take a long time before a relatively complete socialist system is achieved. So we need to believe in socialism, but we're not really sure what socialism is. And this explains why over the next decade, there are so many zigs and zags in Beijing. In over 1980 and 1981, Xi Zhongsheng returns to Beijing.

He goes to work at the secretariat, which is sort of the brain of the party, to work for a man named Hu Yaobang, the new General Secretary of the Party. And as soon as Xi Zhongsheng takes this cushy new post in Beijing, the people think another Cultural Revolution is happening because of the attacks on yet another cultural product, the movie Bitter Love.

Well, what is this movie Bitter Love about? Well, it's about an intellectual who is loyal to the Party, returns from overseas to contribute to socialism, and then is persecuted horribly during the Cultural Revolution. And the movie includes this famous line, you always loved the Party, but did the Party ever really love you?

And Xi Jinping is put in charge of managing this. And he kind of agrees that this kind of thing is dangerous. But he also thinks these Cultural Revolution style attacks are not a good thing. Two years later, there's another campaign, a campaign to eliminate spiritual pollution. Again, people think another Cultural Revolution is coming.

Xi Zhongsheng thinks the whole campaign was distasteful, but at the same time, he's telling foreigners who visit him that spiritual pollution is a real problem. So it's a confusion where you're seeing these challenges, but how you go after them without people thinking another Cultural Revolution is happening is not something that they can figure out.

And these tensions explode in 1987, when Xi Zhongshun's boss at the Secretariat, Hu Yaobang, is removed from power. Now, at the meetings that criticize Hu Yaobang. Some people say to Xi Zhongshun, you went even farther than Hu Yaobang in this bourgeois liberalization. But I don't think that the fall of Hu Yaobang was so much that he had a different political line from Deng Xiaoping as the inherent difficulty of moving forward with the skillet and Charybdis on either side of him.

And if you look at the self criticism that Hu Yaobang gives, he says in theory, reform and opening and the four cardinal principles can be integrated. But in practice it is very hard, and it requires a great deal of political skill. So you can see that the Communist Party of China had trouble explaining what communism was, which means it's unsurprising that they looked overseas for other models.

In 1953, when Xi Zhongshun was the minister of propaganda, the number one slogan in the People's Republic of China was the Soviet Union of today is China's tomorrow. Now they don't say that anymore. But by the way, 1953 was the year that Xi Jinping was born. Xi Jinxun, he's working at the State Council, excuse me, for Zhou Enlai during the 1950s.

What does this bailiwick include? The tens of thousands of experts from the Soviet Union who are sent to China to help them build a new society completely based on the Soviet model. Xi Jiangsheng's very first trip overseas is in 1959. Where does he go? He goes to Hungary.

That's very interesting because it was only three years previously that an insurrection there had raised questions about whether or not communist regimes were as resilient as people thought. On his way back, he stops at the airport in Moscow where he meets a man named Yuri Andropov. Andropov had been the ambassador to of the Soviet Union to Budapest in 1956, and his wife developed mental challenges for the rest of her life because of the terror she felt when she saw Communist Party catters being butchered in the streets of the capital.

Xi Jungchen returns to Moscow just a few months later. It's very bad timing because just as he's living in Beijing, there is an incident on the Sino Indian border and Chinese troops kill Indian soldiers. While Xi Zhongshun is in Moscow the Soviet communists release a statement that takes a neutral position between China and India, even though the Chinese and the Soviets are in a formal alliance.

Beijing is incensed and Xi Zhongshun leaves Moscow early. And when Khrushchev met Mao just a month after that, he said to Mao, said to Khrushchev your statement made the imperialists happy. Now, Mao Zedong was the kind of person who didn't take tactical differences as a sign of reasonable people coming to different conclusions.

He saw Soviet pursuit of detente with the west as a manifestation of something very serious, a degradation of Lenin's legacy and a manifestation of something he called revisionism. Meaning the Soviets weren't really Communists anymore, and that's why they weren't helping China on the international stage in the way that they should be.

And that was one of the reasons why in 1962, Mao was so preoccupied with class struggle. And when Xi Jiangchun was removed from the leadership that year, one of the accusations against him was that he was a Soviet spy. 1981, Xi Zhongsheng returns to Beijing to work on the Secretariat.

One of his jobs is China's relationship with foreign leftist, revolutionary, and Communist parties. Beijing had severed ties with almost all of them during the Cultural Revolution because of the radicalization of foreign policy. And it was Xi's job to find a way of reestablishing ties with them, even as people around the world were wondering whether China was still Communist anymore, because now they are moving in a very revisionist direction.

Now, what's interesting is at this time, over the entire Communist world, they recognize that things aren't going well, and they're trying to figure out a way of how to fix things. And Xi Jinping meets with a representative from Poland in April of 1988, and he tells them that reform waits for no one.

And it was that day that for the first time in years, more strikes appeared in Poland. And it was less than a year after Xi's words that Solidarity was legal. And it was only a few months after that that Communism no longer existed in Poland. When the Italian Communist Party Senator De Asanti visits Beijing around this time, he's struck by how much Xi Zhongshin likes Mikhail Gorbachev.

And in fact, Xi Jinping is watching the Soviets very closely. And he reads a book about Chernobyl written by a Soviet scholar, and he writes a notification on it that says, we also have a lot of mistakes like this in our work. It's certainly true that bureaucratism is much more terrible than radiation.

>> Joseph Torigian: Communism is problem a. Are collapsing all around him. 1990, he writes for People's Daily, his explanation for why China will survive anyways. He says that only the Chinese Communists, who represented the fundamental interest of the proletariat, and the broad masses of people, could find the correct road socialism for China through combining the universal truth of Marxism Leninism with China's revolutionary practice.

So you've got the universal and the particular, but he doesn't say which one matters more. But by saying this, he can kind of say that the reason Communism worked is because China said what communism was going to be for China, and then he says something else which is very interesting, which is what the threat was.

He wrote, an adverse current of negating socialism has appeared in the world. The international hostile forces more intensively pursued the peaceful evolution strategy in an attempt to subvert, and sabotage socialism, meaning the West and Western values. So in other words, when Xi Zhongxun was working in Beijing in the 50s and early 1960s, he's witnessing the beginning of the end of Beijing's communion with the global left.

And by the end of his second tour of duty in the 1980s, he's watching the end of communism as a movement globally, except in a couple places, including North Korea. The Chinese were initially skeptical of the dynastic succession from Kim Il Sung to Kim Jong Il. When Beijing finally decided to support Pyongyang, who was sent to North Korea to express support, Xi Zhongxun.

Now what's interesting is when Xi Zhongxun met with North Koreans, he told them, you need to reform, you need to be more like us, even though Kim Il Sung thought that the Chinese had become revisionists. But what's interesting is, in reports back to Beijing, Xi Zhongxun also wrote that China should learn from the ideological cohesion of the North Koreans.

So you can see over and over he thinks that China can have its cake and eat it too. Now, North Korea didn't collapse, but of course the Soviet Union did. And how did it break apart? Well, it broke apart along creases like a chocolate bar. And where were those creases drawn?

Along ethnic lines. Which gets to the next thing I wanna talk about, which is that Xi Zhongxun was a united front person. He was one of the leading figures, if not the leading figures for Beijing's relationship with ethnic minorities. Why was that? Well, in the last years of the civil war, in the early years of the People's Republic, Xi Zhongxun was head of the so called Northwest Bureau, which included a vast expanse of China.

Which was made up of not only Xinjiang, but also many other Buddhist Tibetan areas and provinces like Qinghai and Gansu, and it was Xi Zhongxun who incorporated these regions into the People's Republic. Now, this was an undoubtedly very bloody process, it's impossible to discount the that this was part of Xi Zhongxun's model of bringing these areas into the People's Republic.

But on the other hand, you see him learning certain things, you see him recognizing that there are easier ways of going about exerting power, such as winning over local power brokers, not moving too fast. Using, in his words, feudalism to overcome feudalism. He's brought to Beijing to work again for Zhou Enlai at the State Council, and he spends about 70% of his time on the United Front, on ethnic relations.

Now, 1958 and 1959, the party decides that the model Xi Zhongxun had introduced in the northwest wasn't working anymore because people weren't hearing the call to communism on their own and force needed to be used. And the Party is at literal war with these people that Xi Zhongxun had told that if they joined the regime, that the regime would be kind to them.

1959, the Dalai Lama flees, and after that, the Party declares its goal of completely remodeling Tibetan society. There is another Lama who remained in China, the Panchen Lama. Now, for people who understand Tibetan history, they know that there were two key religious and political figures, the Dalai Lama, and the Panchen Lama, and the Panchen Lama met Xi Zhongxun for the very first time in 1951, because he was in the Northwest.

And in subsequent decades, the Panchen Lama would speak about how he had a real friendship with Xi Zhongxun. In the early 1960s, the Panchen Lama writes its famous 10,000 character petition to the leadership, talking about the horrors that he witnessed in Tibetan areas, it's Xi Zhongxun who's sent to talk to him and calm him down.

But then, by the end of 1962, when Xi Zhongxun is targeted by the Party, one of the charges against him was that he was an accommodationist to the Panchen Lama and other ethnic religious figures, and that they waved their tail so high precisely because Xi Zhongxun let them think they could take the Party for a ride.

1980, again, Xi Zhongxun goes back to Beijing, and what does he spend most of his time doing? United Front. And boy, is the Party facing a crisis, because in previous years, the Party had seen any manifestation of ethnic difference as a sign of class struggle, which had brought Han ethnic minority relations to a level of crisis in intentions.

And so Xi Zhongxun says, to manage this problem, what they need to do is economic development, address grievances, empower local power brokers, allow religion to come out into the open so it can be controlled. Sort of reminiscent, actually, of the early years of the PRC, and for a few years, it looks like it's working.

But then, 86, 87, you start seeing protests, and the party is faced with a conundrum, which is, are these protests growing pains? Is it a sign that this new model needs to be improved, that it needs to be tweaked or other people in the party thought that actually, when you open things up, you don't win people over they take advantage of you because they're splittists, because they're secessionists.

And so Xi Zhongxun is a man of mixed intentions. He also thinks that maybe too many temples are opening, too many mosques are opening. But ultimately, in March of 1989, it's Deng Xiaoping who decides, facing protests in Lhasa, that they are going to be addressed with martial law and a brutal crackdown, and it signifies this very interesting moment of experimentation and ethnic politics in the People's Republic of China.

But the 1980s were not just a moment in time where people considered a new possible equilibrium in ethnic politics, they were also wondering whether elite politics at the very heart of Zhongnanhai could be managed better to avoid the pathologies of elite politics under the Mao era, especially the explosive question of succession.

Now, if you wanted to ask someone from Chinese history why succession politics were so dangerous, one person it would be good to ask is Xi Zhongxun. Why? Well, as I've alluded to already, in the 50s and part of the 60s, he was the right hand man to Zhou Enlai at the Secretariat.

Excuse me, the State Council. Zhou Enlai, of course, was the premier, and in the 1980s, Xi Zhongxun is the right hand man to Hu Yaobang working at the Secretariat. So in other words. Twice he was the Chief Deputy to the Chief Deputy. And what kinds of things would he have witnessed?

Well, you may think that to read a book that's not about Mao or Deng, that all they did was basically take what the top leader told them to do, and that was that. Well, the life of Xi Zhongxun shows something else, which is it is not that simple at all.

And this two line system is actually quite dangerous. And there's lots of reasons for that. One is that these implementers often face an impossible situation. On the one hand, they were supposed to achieve these goals, on the other hand, they were also supposed to achieve these goals. Sometimes those goals conflicted with each other.

Sometimes it wasn't clear how they were supposed to achieve those goals. Sometimes it wasn't clear which goal mattered more. And if you go too far in one direction, you're gonna be accused of one ideological heresy. If you move too far in the other direction, you're gonna be accused of another ideological heresy.

Meanwhile, you have all these other people in the elite who hate you, who are going to Mao and saying, this other person doesn't correctly intuit what you want, and therefore I'm a better person to execute what it is your wishes are. And Mao and Deng, by the way, they were not attentive to detail.

They were people who constantly felt the need to give their deputies at least some space to make decisions. Mao was distant and not detail-oriented because he viewed himself as kind of of like a sage king, a wise emperor who wanted to take a step back from the decision-making so that he could think big thoughts.

And Deng, he was someone who wasn't like a big thinker, but he was also someone who wasn't paying attention to the day-to-day. And so even when Deng was leading the secretary to the 1950s, he didn't work nights, at night he played cards. Now, I'm not saying that Deng was a moron.

In fact, he was quite a powerful leader because what he was good at was at the end of a meeting saying, this is what the meeting was about, and this is what we're gonna do next. And people were amazed that he could just take a whole bunch of people arguing for several hours and then make a decision.

But nevertheless, these were people who, if they're not constantly telling you what they want and think, and possibly also changing their mind and evolving. And you're given tasks that are inherently impossible, and they're testing you to see whether you're a good successor, and they want to be absolutely sure that you're the right person.

Boy, is that hard to get right? Boy, is that hard to get right? And Xi Zhongxun kept witnessing it. 1958, the beginning of the Great Leap Forward. Zhou Enlai is at a conference and gives a five-hour humiliating self-criticism. He goes back to Beijing, where Xi Zhongxun is waiting for him, and he says to Xi Zhongxun, I can't do anything right, Mao just always keeps criticizing me.

Because Zhou is saying this because he's not opposing Mao, it's just he can't figure out what Mao wants. And Xi Zhongxun says to Zhou Enlai, we'll take responsibility together. The 1980s, now Deng is the leader, Hu Yaobang is the chief deputy. Hu Yaobang thinks that he has Deng's absolute trust.

He says, Deng understands me, he knows that I don't engage in conspiracies and machinations. And he says that Deng understands I know what my role is, which is not the head but the bottom of the foot for the Chinese speakers, right? Xi Zhongxun keeps saying to Hu Yaobang, you need to go see Deng more.

Xi Zhongxun's been around the block, he's much older and more experienced than Hu Yaobang. Hu Yaobang's greatest mistake was at a private meeting with Deng Xiaoping, Deng said, I'm going to retire, and Hu Yaobang said, I support your decision. And Deng Xiaoping concluded that Hu Yaobang was trying to push him out.

When Hu Yaobang was attacked in early 1987, he said, I never told Deng that he should resign. And Xi Zhongxun yelled out loudly so people could hear him, I heard Hu Yaobang say this three times.

>> Joseph Torigian: And Xi Zhongxun said during the 1980s, we've learned the lessons of strongman rule, we can't let this happen again.

But he still acquiesced to the fall of Hu Yaobang, anyways.

>> Joseph Torigian: Now I wanna talk about young people. Now, one of the triggers for Hu Yaobang's fall was student protests. And that's ironic because it's how to manage succession at the top and how to win over the younger generation at the bottom that were the two most existential questions for Xi Zhongxun.

Xi Zhongxun explicitly said that history and reality teach us that enemy forces at home and abroad have always concentrated their goal of peaceful evolution in young people. The fight for young people is a life and death struggle without gunpowder. It is related to whether there will be successors to the socialist nation for which we in the older generation risked our lives in battles across the country to found.

And it is related to whether the cause of socialism and communism will never lose its red color for thousands of years. Now, Xi Zhongxun was someone who thought a lot about how to win over young people to the cause. In 1952, perhaps the most foundational moment in the history of the Chinese Communist Party, the Yan'an Rectification.

So Yan'an is the base area, and rectification is the campaign that Mao launched to take these young people who are coming to the base areas, often from the cities and entitled backgrounds. These young people, who often were arrogant, entitled, had their own big ideas, one who had hero complexes, and forged them into something new, screws, basically tools for the revolution.

Now, that's not my valued language, that's the kind of language that they used at the time. So the question was how you take these people who understood that they wanted to be reforged, but turn them into something new was an emotionally grueling and devastating experience. It really included the total transformation of these people's lives.

And Xi Zhongxun was the dean of a university in Yan'an when it happened, which means that he was at the very heart of it. 1943, he's the party boss of a region named Suide, which is northeast of the city of Yan'an. And that's when rectification turns into something new, as it becomes more radical, a spy hunt, and it goes off the rails.

And many young people are accused of working for the Nationalists, and not a single one of them are really guilty. And Xi Zhongxun's approach is so radical that even notorious figures like Kang Sheng, known as the barrier of the Chinese Communist Party, is impressed and says that other regions should use it as a model.

The 1950s, the question of young people appears again because Xi Zhongxun is raising his own family in the capital. How are we gonna raise these new people? Well, it was an existential question, because the old guard wanted to figure out a way to ensure that these young people who are growing up in a privileged lifestyle don't lose their revolutionary line.

And so that is one of the reasons why the Xi family was notoriously disciplinarian. That's not just because Xi Zhongxun was a peasant, but it was because there was a political background that was based on the idea that you needed to be tough, even brutal. To make sure that young people grew up to be good inheritors of the revolution.

1966, 1967, the question of young people is again a question of concern for Xi Zhongxun because of who? The Red Guards. Xi Zhongxun is already kicked out of the leadership, he's working at a factory in Henan province. Red Guards from neighboring Shanxi Province kidnap him, put a mask on his face, throw him on a train, bring him to a dormitory, incarcerate him there for several months, and bring him repeatedly to struggle sessions where he, He loses hearing in one of his ears.

After the Cultural Revolution, we have the opposite problem, which is that young people are so disgusted by the tragedy and disaster of the Cultural Revolution that they don't believe in anything anymore. And they wanna make up for lost time. They wanna have fun, they wanna go overseas, they wanna make money, they wanna date.

And so when the party is figuring out who they're gonna rely on in the next generation, one possibility are the princelings, the offspring. But they're not really a wonderful choice either. People don't like them because many of the early Red Guards were princelings. And now people in society think that these princelings are benefiting from nepotism and they're entitled, and people don't like them very much.

>> Joseph Torigian: And then, of course, the question of young people comes to a head on June 4, the student protests. Now, why are students protesting? Because Hu Yaobang has died. Shortly after Hu Yaobang's death, and the students are getting more active, a member of the Politburo Standing Committee goes to Xi Zhongxun's office in the National People's Congress, the Chinese legislature, and starts crying.

And Xi Zhongxun says, now is not the time to cry. And he complains about how when Hu Yaobang was removed from power, so many other people wanted to be the general secretary. Now, people, I think, already know a lot about how the general secretary at the time, a man named Zhao Ziyang, refused to go along with the crackdown.

But what people don't know is that after Zhao Ziyang was isolated, the greatest hope among the leadership for a peaceful solution went to the National People's Congress. The head of the National People's Congress was not in Beijing at the time. In fact, he was in Canada, in the United States.

And the highest ranking official who remained was Xi Zhongxun, the first vice chairman. He is writing notifications saying that the way that the party leaders in Zhejiang Province are moving forward got it right, which is to talk to the students, to win them over, to not take things so seriously that you make the situation even worse.

He's complaining that the premier, a man named Lee Peng, once has no scruples about suppression. Nevertheless, after several days of other senior revolutionaries putting pressure on Xi Zhongsheng, even before the crackdown, Xi Zhongxun comes out in support of martial law. And after martial law is declared, after 700 students who hoped that the National People's Congress would save them were killed, he comes out again repeatedly and openly to express support for the People's Liberation Army.

1990, a few months later, there's another meeting of the national people's congress. Xi zhongxun screams at the premier, sleeps on the couch, starts saying all these odd things that make people wonder about how he's doing. And a few days later, he goes to the south, doesn't return to Beijing for nine years.

And in these diaries written by a man named Li Rui, who was a close associate of Xi zhongxun, Xi's behavior was the result of, quote, years of pent up frustrations. And you can see that quote in the open diary over there in the corner. So what does this all mean for how we think about Xi Jinping?

Well, it's certainly the case that many people were surprised by Xi Jinping because of their understanding of his father, who was seen as a reformer. Li Rui, the man who I just mentioned and whose daughter is in the audience today on his deathbed, said to her, as well as one of the sons of Hu yaobang, that he simply could not understand why Xi Jinping was Xi Jinping.

Because his father was such a good person, and asked them to figure out what happened. Now in oy, Li Rui kind of got the last laugh because it's his diaries that are here at the hoover that made my book possible. That doesn't provide full answers, but maybe some context for thinking about Xi Jinping.

And I don't wanna draw a straight line from Xi Zhongxun to Xi Jinping because a man's mind is not a pool table. It's not that simple. And even Xi Zhongxun's own children have drawn different conclusions about the meaning of their father's life. One, as I said, killed herself during the cultural revolution.

One became a close associate of these pro reform senior intellectuals and comrades in Beijing who wanted constitutionalism. Other children made a lot of money, but Xi Jinping chose a different path. And there's a question at the heart of that decision, because Xi Jinping, who knows so much about the darker side of party history and who saw his father so heavily mistreated, committed his life to the party in a fundamental way.

And that really is a puzzle, because if you look at dissidents in both the Soviet union and China, including Benjamin Nathan's book, it's true that the story of their political awakening often had to do with learning what their parents did or did not do in the past. When their parents made choices that either caused or facilitated terrible tragedies that left behind political landmines for future generations, because younger people might someday ask, what kind of system could unleash such violence?

And why didn't my parents say no when the party told them to hurt people? But the children of powerful officials would have seen something else, too, that was very important, which is seeing what bending to the party's interests did to the people who bended. And it's true that in most cases, not bending would have only made things worse.

Nevertheless, a rational choice can have emotional repercussions, and many party leaders felt intense shame or guilt over their behavior, and it could affect their mental health. So Xi Jinping was someone who saw the party at its worst, including in ways that might be a little surprising for people who don't look at the Communist Party a lot.

And it's not surprising in a way that Xi Jinping himself admitted to going through a period of doubt in the revolution. But what's interesting is he says that precisely because he went through that doubt and returned to the cause, that his belief is so unshakable and is so much stronger than anyone else.

So we can wonder what kind of suffering leads to dedication and what leads to alienation. But for Xi Jinping, at least, very clearly led to dedication. And he seems to have asked, how could I defy a cause for which my father suffered so much? How can I win pride and legacy for a family that was humiliated so many times?

And how can I prove the worth of the Xi family? And his answer to those questions is quite breathtaking in terms of ambition, which is that he wants no less than to break the wheel of dynastic cycles that have marked Chinese history for millennia through a continuous re baptism in the fires of revolution.

And how is he trying to do that? Well, in terms of ideology, he's drawing from his father's story as someone who saw the dangers of taking ideology too seriously, as well as not taking it seriously enough. To pursue an ideological agenda that is at least supposed to avoid the extremism of the Mao era and the materialism of the Deng era.

Globally, he's trying to make the case that Western liberalism is not the end of history. Third, he's trying to assimilate the border regions in a way that makes the same impossible. Fourth, he's drawing from his father's story as a close associate to Mao and Deng's top deputies, witness to the dangers of succession politics by ending the succession, at least for now.

And he's using the Party's own history as moral education to win over young people, to commit their lives once again to the nation and party. And it's for that reason I think we should go back and see what exactly that history is, which is what I try to do in my book.

Let me finish with a coda. There's one other person in Xi Jinping's life that was fascinated by the story of the Amana colonies, Wang Huning. I see some people nodding because they know that he is sort of the ideological czar in Beijing. He visited the United States in the 1980s, and he wrote a book called America Against America.

And he has a chapter about The Amana colonies, in which he says that, yeah, there were lots of structural problems, but what was the biggest? They didn't get the ideology story right, and it meant young people didn't wanna do it again. So Xi Jinping recently said that Western imperialists place their bets of peaceful evolution not on the first generation who won the revolution or the second generation that was brought up by the revolutionaries, but the third and fourth generation.

And he's calling them to once again listen to this clarion of dedicating their lives to sacrifice and mission and national rejuvenation, collectivist values, and I think that many young people like Xi Zhongfen and Xi Jinping find that meaningful. But I also think that there are signs that some Chinese are weary of living ardently, and they find inspiration in a call to eat bitterness, like their forebears did, and might decide someday to do something about it.

And that's a particularly meaningful question to think about today, which is the eve of the 36th anniversary of June 4, Tiananmen Square. So I'll stop there, thank you.

>> Stephen Kotkin: So I'm struck by the fact that the protagonist of the book is the Communist Party.

>> Joseph Torigian: Yeah.

>> Stephen Kotkin: We've become very used to books on China, talks on China, expertise on China, talking about special economic zones, entrepreneurs, science and technology, manufacturing, skyscrapers, airports, and this amazing story of material success on unprecedented scale in a short period time.

And during the study of all of those phenomena which are real and which are important, there was, in many cases not all, a de-emphasis on matters of ideology, on matters of the party structure. On what people might or might not be learning in Party school, the fact that they were still going to Party school as a requirement to become a cadre.

So in some ways you're part of the movement to bring the ideology and the Party back to the center of the story, not to completely displace the advances, material progress. But to help us understand that there's something more in China under Communist rule, in fact it is Communist rule, than the great material success.

So you've got a story of the peculiarities of the Leninist structure, organizationally very prominent in the book, but you've also got a story of the search for purpose and meaning in life. It's a story of spirituality, it's a story of emotions, it's a story of feelings, connectedness, of finding purpose, losing purpose, finding purpose again.

Of subordination, of commitment, of ideals, even when the ideals are traduced or the ideals lead to massive bloodshed, as they do time and time again. It's still about ideals, and it's still about their emotions, and it's still about their search for meaning and their identification with this cause.

And that runs through the entire book, as well as the father who's got all of these amazing positions. I mean, what more could he have been responsible for, it's just astonishing, the relations with the Soviet Union, how big was that? The borderlands and the relations with the national minorities, the governing structures and Joann Lai's government and the Party Secretariat.

It's everything rolled up into a single figure again, and again, and again, of course, not all simultaneously, but through time. And then he's got more than one wife, and more than one brood of children, and so, one of those children then emerges in this fantastic story as well.

I mean, it's like fiction in some ways, that this could all come together in a single story, and then, of course, we have the diaries of LeRoy right here in house. Just a guy who saw the inside of all of this for a really long period of time and recorded it scrupulously, and it was preserved through thick and thin, of course, thanks to the family.

>> Stephen Kotkin: We have to say, and it's available for you and many other researchers, just like the Chiang Kai Shek diaries, just enormous demand for them. And so tell us a little more about how you came to this side of the story, not the side of the story of the skyscrapers and the airports, and the entrepreneurialism, and the special economic zones, again, all of which is real.

But the side of the story where the Party's interests come first.

>> Joseph Torigian: So one of the things I tried to do with this book was to demonstrate that for members of the Chinese Communist Party, even though it has this ideal of turning people into screws, as I said it during my talk, they're still human beings.

And so in the Chinese language, you have these two different words, one for partyness and another for humaneness or humanness. And often they worked in conjunction for Xi Zhongshun, I don't wanna say that it was a total divergence, but it's also true that when you put yourself into the hands of an organization that is totalizing, that you need to figure out how to continuously change yourself to remain someone who is useful to it.

And so Xi Zhongsheng repeatedly said throughout his life that individualism was like a virus or like a bacteria, and that if you allowed it to continue to grow, then it would. So there's never an equilibrium, there's never a stasis, there needs to be this constant struggle, this constant leaning forward, this constant finding out how to eliminate your own strongly held views so that you can line them up with the Party.

And rationally, I think he understood that, and emotionally, he could intuit the value of it. It was exciting to be a member of the Party, I mean, the Party was a manifestation of a world historical first, and you were the leader. And you were able to emerge from these constant defeats in your doubts, and the Party almost annihilated on so many occasions, and here you came through.

So for him to deny the Party would have meant denying himself, right? So in the West, we tend to think of Chinese leaders as either good or bad, pro reform or anti reform, and Xi Zhongxun was supposedly one of the best. One of the most humane, one of the ones who constantly thought that the Party could do a less brutal approach.

And there is some truth to that, but at the same time, by taking someone like that and show how complicated even he was, I think is enormously revealing for how the Party works.

>> Stephen Kotkin: Yeah, but how did you know to do that? In other words, where did you come from to focus on this emotional To know side, so you could have focused on the fact that the party is killing people, it's killing their friends, it's putting them in prison, and that's the main story or the predominant story, let's say you've got that, and that's very important.

You have no illusions about the nature of party rule, but at the same time you've got this human story of identification, emotions, tragedy, belief, conviction through hardship. So that when they say things like eat, bitterness, infamously, that comes from a place that's not just about imposing rule on people, but it's through life experiences that they've had that they find meaningful.

So how did it dawn on you that was the story?

>> Joseph Torigian: You're asking a more reflective question than I realized you were asking the first time. It's more about a little more about me, I suppose. That's a tougher one that requires a little bit more thought. I think that one way that I came to it really was I didn't come to the project with any preconceived notions of what the book was gonna be.

To be frank with you, the book was a little bit of an accident in the sense that I was asked to write a paper about Xi Jinping for a journal. And I said, I mostly do party history. I'm not sure whether I can be useful or not. And then the person said, well, write about party history in the Xi family.

And then I thought, okay, I'll write an article about Xi Jiangsheng and Xi Jinping. And then it became an article, two articles, one about Xi Zhongshun and one about Xi Jinping. And then it became a 700 page book about Xi Zhongshun with some parts about it with Xi Jinping.

So I didn't say, boy, I really want to write a book about emotions, or boy, I really want to write a book about ideology. But I tried to come to the evidence and allow the evidence to speak for itself. And that's not to say that facts are facts and all you need to do is dig them up and put them on the page and they're meaningful.

Because even deciding what facts matter or that it is a fact requires some level of interpretation and analysis, right? And so I've talked to Orville about this, right? The book is not like a psychological portrait of Xi Jinping, but emotions and affect. It's at the very heart of it.

So what I tried to do was to provide a story that did justice to their lives to serve as a reference for people who might want to take the next step and say what that meaning is. And so that was the purpose of the book, was to give people a sense of what the Party was like, how the Party functioned, and what it was like for China's current leader to grow up in that kind of milieu.

But there wasn't any particular, I think, methodological prior that sensitized me to allowing me to see that as the big story. It was just as a scholar, my main center of gravity is to get the story right. And I think that when you're dealing with life and death in the sense that lots of people.

My book is about, as I said before, kind of a book about suffering. And when you do a book like that, you want to get it right, right? And so to do that, like, I put a lot of work into it to help understand why these people were dying or why these people were causing other people to die.

And it's just the story that emerged was the story that emerged. I feel like this is not a very good answer, but it's the best I can do right now.

>> Stephen Kotkin: I think it is a very good answer. Let's talk before we open it up to the audience, which we'll do in a little bit.

Let's talk a little bit about the materials that you used. So I have a similar trajectory, at least in my own head, of rediscovering the centrality of the Party and of ideology and of meaning and affect as part of the moral squalor and brutality of communism at the same time.

And I also ended up on the biographical track. And so I kind of get some of this where you came from. But in my case, I had this motherload of documentation because the regime fell, it imploded, but it preserved its documentation. And that documentation, again, is here under our own roof, thanks to the great work of Charles Palm and his colleagues and the continued work of Eric Waken and his colleagues.

And so I was overwhelmed with too much material, even though during the existence of the regime and the leaders, they didn't want you to see it. Nonetheless, when it imploded, it became everything and anything. And your trouble was there was too much to look at. So the Chinese Communist regime is still in power, and they're not.

They didn't implode. Their documentation is official documentation. The state and the party archives are not sitting here. We have really important documentation that you went through, but not the main documentation of the phenomenon of the regime. So how is it possible without the regime falling, without all of their materials being declassified and open?

How is it possible to write a book that's reliable, scrupulous, that you can make conclusions about specific episodes that either they're trying to conceal or mislead on. What type of materials did you work on? Where are they located, in addition to Hoover? And what made possible not just a Leroy diaries, but what made possible a book that's scrupulous, like the one that you delivered?

>> Joseph Torigian: When these senior revolutionaries and intellectuals who wanted China to move in a constitutionalist direction first started to fear that Xi Jinping was going to be Xi Jinping. It was in a speech that he gave in 2012, and he gave several explanations for the collapse of the Soviet Union.

But one of them was, they lost control of their history. And he said that because for him, you need to have these ideals and conviction. And for that, you need to believe that the Party is an inevitable force in Chinese history and the only way of organization that can allow China to reclaim its rightful place in the world.

And the story of his father, in many ways, is a story about how people who fought in this organization saw how their histories were characterized as absolutely existential, because that was what their whole lives were all about. And how the Party described them was something that they cared so much about.

So for those reasons, it wasn't an easy book to write. And so you can't just go to one archive and collect all the material and write it up. You need to have kind of a detective mindset. You need to be sensitive to possibilities, not limitations. And you need to recognize that it's an iterative process.

So Roderick McFarchroy once said to me that a party historically criticized him for getting something wrong. And his response was, of course I got it wrong. I didn't know it happened. And it's just this very frank response to a question. And I guess your earlier question was kind of brushing up against my intellectual background and meeting people like McFarlane or Fred Tevis.

They could change their mind. And they cared so much about getting the story right. And that was a little bit different from some academic approaches that kind of come with very strong priors that are harder to change when you meet up with the evidence. So a quick aside to that.

I don't think in terms of good and bad evidence. I think in terms of getting as much evidence as I can and parsing it and interpreting it and putting together a mosaic that in some places is colored and better in some cases is not. And to do justice to the The historical record, when doubts continue.

And to be honest, the system is confusing even to people at the very top. And in the Li Ray diaries, he writes down lots of rumors that turned out not to be true, even though Li Ray was a smart guy. And so the fact that that is so confusing is also a story of Xi Zhongsheng to kind of describe how he was in a system where it was impossible to know what other people were really thinking, precisely because it was such a totalizing organization.

And so one thing you can do is, I don't know if you've heard this term Mosaic theory, but very often, even with official sources that come out, they don't know what I can do with it, because they don't know the kind of context that I can put it into.

So there is this chronology, three or four books that came out right before my book was done. And if I had read it at the beginning, it wouldn't have been that interesting, but when I read it with everything I had already known, I don't know if they knew or not, but it could be explosive in my hands.

Once I could put it with memoirs and blah, blah, blah, but just on the nitty gritty of the sources, a lot of primary documents, including archives, are available at American libraries, cuz they fell off the back of a truck or something, and they somehow got here, a lot of it, right.

Lots of stuff published in Hong Kong and Taiwan outside of censorship. My book could not have been possible if I didn't draw on the historians of Chinese people themselves that were published during a period of openness, before Xi Jinping, or outside of censorship in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

And I also did things like I saw every time that he met with a foreigner, and then I went to their archives or interviewed those people, so he knew the Dalai Lama. I talked to the Dalai Lama, I got the verbatim transcripts of the negotiations between the Dalai Lama's emissaries and Xi zhongshuan in the 1980s in Tibetan and had them translated into English.

I went to the Italian Communist Party archives, I went to the Serbian archives, I went to the Polish archives. And then slowly, you can kind of put together a picture that's not complete archives, but at least gives us enough that it's, I think, useful to get a sense of what his life was generally about.

>> Stephen Kotkin: The internationalism of communism turns out to be really valuable for researchers.

>> Joseph Torigian: Absolutely.

>> Stephen Kotkin: And also the fact that communism is so proud of itself and so talkative about itself that the official sources which are endless, and they want you to think a certain thing, but you can actually discover things they don't want you to think in those official materials because you've got that mosaic of all.

>> Joseph Torigian: By the way, when they lie, it's also very revealing because when you see a lie in a memoir, that tells you something, and when you see them actually Dr. A public version of a speech, you know exactly what they're worried about. So that's also a form of evidence, the lying itself is a form of evidence, like how they characterize the past as a form of evidence.

And when rumors are true, the fact that the rumor existed in the first place is also something that has its own social power that should be recognized, so you can see I get excited in this direction of discussion, so.

>> Stephen Kotkin: I think it's really important for us to understand how an important book like this is possible.

We sometimes have the impression that the regime is hiding everything, and therefore it's just really hard to write a reliable book that's factually rich, and not speculative about episodes or following rumors as if they're true. Or just writing what we wanna be true, because we don't like the regime or the specific person.

So I think it's just important for people to understand the level of scholarship that's possible despite the obstacles that the regime will put in people's lives.

>> Joseph Torigian: Yeah, one of the other purposes of this book was to leave a lot of breadcrumbs for other people who want to do party history, so have fun with these guys.

>> Stephen Kotkin: At which point we'll go to the audience, we have some microphones. If you'll raise your hand and identify yourself. We got one in the very back there, thank you.

>> Speaker 4: Thank you so much for giving the wonderful lecture. This is a three part question. I said a little at the beginning of your speech that we're interested in Xi Jinxing because we are more interested in Xi Jinping.

So by writing the book, how much the life of Xi Jinxing give you more clarity of who Xi Jinping is? And that's one, two is, do you think, I know it's hard question, so do you think the Xi Jinping the hard line stance have been taken surprise everybody including both overseas and within China.

So if you have to take a guess, is that some switch in his career, or he's like a lay low watching his son die kind of bide his time, and then that's always who is? The third question is, since you already wrote the book of Xi Jin the father, are you gonna move on to write about the son?

>> Stephen Kotkin: Okay, thank you.

>> Joseph Torigian: So the book is about Xi Zhongshun, not Xi Jinping, and I think it does have relevance for Xi Jinping in two ways. One is that it's a book about the Party and how the Party works. And so certainly, if you look at the details that I found that are new in the book about the relationship between Xi Zhongshun and Xi Jinping, certain things that he does becomes meaningful in that context.

And at the very least, who he became was possible, maybe even prime, because of the history as I describe it in my book. But I also don't wanna say that xi Jinping was 100% Xi Jinping in 2012, because we just don't know, in fact, I think that he also had a trajectory.

There's a very interesting quote in my book from Xi Zhongshun where he says privately that power corrupts and changes people. And so one of the other funny things that Li Ray says in his diaries is, he keeps meeting these people who he was really nice to, and then they become the top leader, and they change, and he gets really upset about it, right?

So in that sense, part of what I say in my book about Xi Zhongshun is that he himself was a product of multiple centers of gravity, and he could change his mind. And sometimes it could be hard to guess what he would do in a particular situation, because politicians are flexible and pragmatic, and concrete situations have their own specific characteristics.

And so I think that applies to Xi Jinping, just like it does to Xi Zhongshun. But most meaningfully, I think that what the book says about Xi Jinping is how he faces the same dilemmas that his predecessors face. And what he faces are dilemmas that can be managed, not problems that can be solved.

Which means that he's not changing the nature of the Party, but he's bringing his own approach to addressing these problems. And the way that he describes it is kinda middle approach, right? Of learning from the past and not going too far in any direction. And you can see how that works in theory, but you can also wonder whether that's just kind of muddling through in another way.

And whether or not by trying to immortalize the regime, he may actually be accelerating forces in society that will be hard to manage after he finally leaves the scene, which is something I think that's interesting to think about. I haven't decided whether I'll write a biography of Xi Jinping yet.

When I think of everything I would need to do to do it justice, I get a little dizzy, but maybe someday.

>> Stephen Kotkin: Yes, who's next? Yes, over here in the front. You need the microphone because we have a big online audience.

>> Speaker 5: Okay, well, I'm interested in the history that you've described, and the work that you've done is kind of a profound study that I had no idea that something like this could be done or that anybody was doing this.

But I'm really interested in what's next, and how does the work that you have done cause you to have any view about what influence it may have on what's going to happen tomorrow? And then take that a little bit further, let's go up. And let's take a look at the next generation of people who are gonna be living in a society that has this history to build on.

But what can they make of it? And what are you hoping will come from the work that you've done? What's your ambition with regard to the work that you've done?

>> Joseph Torigian: So I think that what history can do is allow us to structure questions, question assumptions, see possibilities, make the limited evidence that we do have more manageable, give us an interpretive lens for how we might be able to understand it.

And that gives us the tools to forecast different scenarios and allows us to think about possible directions in the future and what things would have to happen for those outcomes. But it can't tell you what's gonna happen tomorrow, it can give you context that is a useful tool for watching as things change and to make sense of it.

So I think sometimes when people look at my book, they try to say what it means for the tariff war, right, and whether Xi Jinping will back down. In fact, that's how they talked about it on Taiwanese news recently. And so I think it's useful to read my book if you wanna wrestle with that question.

But I also don't think it's gonna tell you when they're gonna have the phone call, right? So in that sense, right? So one purpose of the book is I wanted to give voice to these people, I wanted to do justice to their lives. And that's just like an intrinsic value, it's not like an instrumental value, right?

I think that's part of the history it's just that people, especially who suffer so much, we should figure out what happened and their name should be in a book somewhere. And that's one of the great regrets of my book is when I was cutting to meet word count, that some of those stories are kind of lost.

But part of it also is to facilitate other people to draw meaning from it and draw their own conclusions. So as I said, there's a lot of interpretation to figure out what matters and how to say what happened in the past. But I also didn't want to draw too fine of a conclusion, sometimes because the conclusions are obvious, and maybe more obvious without me saying them.

But because as I said, different people find different meaning in suffering, even in the same family, and this was a story of extreme suffering. So to the extent that this book facilitates people thinking about that, it facilitates people thinking about the immortal conundrum of servicing an organization and putting the organization's interests first.

But also remaining human, how you balance tactics and principles, all of these are parts of the book.

>> Stephen Kotkin: Yes, let's go to the woman in the back, thank you.