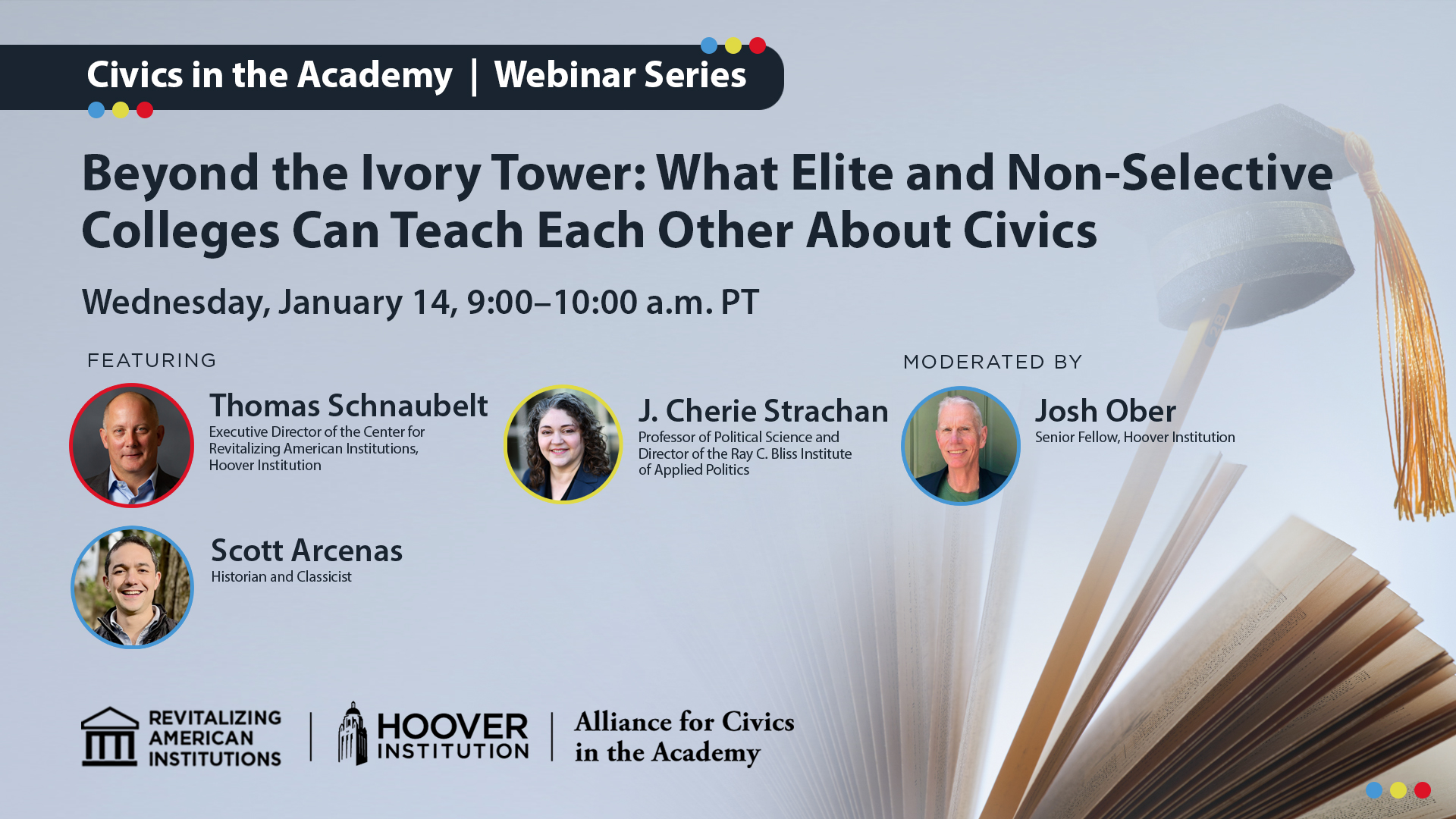

The Alliance for Civics in the Academy hosted "Beyond the Ivory Tower: What Elite and Non-Selective Colleges Can Teach Each Other About Civics" with Thomas Schnaubelt, J. Cherie Strachan, Scott Arcenas, and Josiah Ober on January 14, 2026, from 9:00-10:00 a.m. PT.

As higher education experiences a renewal of interest in civic education, much of the attention and resources have focused on elite universities. Yet non-selective institutions have a long history of producing civically minded students and often maintain deep engagement with the communities in which they are embedded. This webinar explores the comparative advantages and challenges of elite and non-selective institutions in preparing students for effective citizenship, what each can learn from the other, and practical pathways for collaboration that draw on their respective strengths.

- Welcome to the fourth webinar, sponsored by the Alliance for Civics in the academy. I am Josh Ober. I co-direct the Stanford Civics Initiative, sit on the Executive Committee of the Alliance, which was launched just a year ago as a community of practice or practitioners of civic education in America's colleges and universities membership in the Alliance. The alliance civics in the academy is open. If you're not yet a member, we urge you to join us. There's an application link in the chat, or it'll appear there momentarily. If you're not yet a member, we urge you to join us once again. Please, please do so. The series features in depth discussions on the practice and pedagogy of civics in higher education. And it's meant to foster dialogue to share best practices and contribute to pluralistic frameworks in the fast changing field of civics in American higher education. Our alliance also provides seed grants for members to host meetings on a topic of importance to civics education. We disseminate practical resources, including course syllabi and program descriptions, and we support dialogue by publishing members, commentary, research, and other field building work. If you'd like to submit resources and commentary or have other inquiries about getting involved in the a CA, please send an email to us at the email site that's in the chat. That's hoover aca@stanford.edu. Much of the attention on civics in higher education in the national press has concerned either new programs at relatively well endowed, highly selective elite universities like Stanford or Yale, or at new schools of civics established by state legislatures at flagship public universities in, for example, Texas, Kentucky, Ohio, Florida. But most American college and university students do not attend these universities. Most of them attend what are known nows colloquially, any way colloquially. Anyway, non-selective institutions, NSIs, that is colleges and universities that are closely connected to a local community and admit most of those who apply. Moreover, there's a long tradition of civic engagement and civic education at NSAs. Today, what we hope to learn, what we hope to do is to learn from the experience of the ambition of faculty and students at NSIs, and to better understand what they have to say about the future of civic education in America. So our panelists today are Sheri Stren, who is Director of the Bliss Institute of Applied Politics and Professor of Politics at University of Akron Theree applied civic education pedagogy research focuses on facilitating student led deliberation and deliberative discussions, and on enhancing the political socialization that occurs within college student organizations. Next, Scott Harena is an associate professor in World Languages and Cultures at the University of Montana at Missoula. His first book, political Violence in Ancient Greece, was published by Cambridge University Press exactly nine days ago, if I've got that right, Scott. Yeah. So congratulations on that. It's a, it's a big first. Scott teaches courses of the history of democracy and citizenship in both the ancient and modern world. Tom Schnabel is executive director of the Center for Revitalizing American Institutions at the Hoover Institution. Tom was however, formerly along with various other jobs that he's held at Stanford and other institutions, but was formerly Dean for Community Engagement and Civic Learning at the University of Wisconsin Parkside, and was the founding executive director of the Wisconsin Campus Compact. My own background, just to throw that in, was not uniquely at places like Stanford. I spent the first 10 years of my career at Montana State University. So we all have some engagement with non-selective institutions. I'd like to Cherise got Tom, I'd like to give you each a few minutes just to give us a bit of your own history of work in this area of CI Civics. Cherie, why don't you start, I know that you've been in deeply involved in civic pedagogy for a, a long time now, and you have a lot of experience in this area.

- Oh, thank you. So I spent most of my career at regional Publix, and I'm a political scientist, and I did some work, you know, well over a decade ago on polarization. It was one of the, a traditional political science piece where my co-author and I really said, you know, this isn't going away and it's gonna get worse. Like, there's no incentive structure to make it go away. And you know, much to my dismay, it, it has gotten worse. But at that point in time, I was so disturbed by my own research finding, and I had been doing some work with applied pedagogy research and, and civic engagement work. But I, I was at a regional public and I could shift half of my research effort to that kind of of research and really became deeply involved in, in not only trying to teach for democratic capacity, not just for, you know, not just for political science disciplinary knowledge, but adding the learning objectives of civic skills, civic knowledge and civic dispositions, and assessing it so that I could persuade other people that there were best practices. And through that, I really became connected to, you know, there's a deep movement that started around the 1980s, you know, that that really initially focused on service learning and is the reason why service learning and campus community engagement centers are so ubiquitous, which has broadened out and, and sort of brought, widened their, their approaches in experiential learning over time, but really became connected to that, which is really a horizontal movement, right? To try to mobilize faculty across these kinds of institutions that have the bulk of college students and to embed civic learning and to make sure that they have those experiences before they graduate. And that's, you know, that involvement was, was how I landed the position where I am now. They, they wanted that focus, applied politics at this point in time can't just be training consultants and people how to run for office. It has to include citizenship. So here I am.

- Terrific. Thank you. Scott. Why don't you give us a little of your sense of how you got involved in teaching civics out in Montana?

- Absolutely. So just wanna focus on kind of how I came to believe that NSI, that's the term we're using for non-selective institutions, for those of you who aren't in the know with the ever evolving lingo. But anyway, how I came to believe that NSI is really ought to be at the heart of civic education. And in short, it's pretty simple. I started to work at a poorly funded public institution in a state with a desperate need for civic education. And this in combination with the fact that I'd attended public, elementary and junior high schools in Casper, Wyoming, helped me realize in the first place just how atypical and frankly, weird the elite institutions where I'd spent the last 10 to 15 years really were two, just how poorly students and faculty at elite institutions understood what's going on in the rest of the country. Three, how much that lack of understanding compromises their ability to do civic education well. And then finally, thanks to my unusual combination of elite and non elite background, it helped me realize that I might be able to make a real difference by establishing a model for symbiotic partnerships in civic education between elite and non elite institutions. And as I'll explain later on, I, I just really think this is crucial because if elite institutions want to save the country through civic ed, as they quite rightly want to do, they aren't gonna be able to do it alone. They're really gonna have to collaborate and in many ways take a step back and let public institutions that have complimentary strengths and weaknesses play an important role. And so, just quickly, what I mean by complimentary strengths and weaknesses, the fact that right, non-selective institutions have a lot less money, but they have a lot more in, they have a lot more students and a lot closer connections with rural communities, for example, that feel alienated for higher education. And so, again, I think that non-selective institutions really be, need to be at the core of civic education if it's going to make the impact that we'd all like it to.

- That's terrific. Thank you very much. Tom. Why don't you give us a little sense of where you're coming from.

- Yeah, thanks Josh and Cherie and Scott, it's good to be here with you. Not surprisingly, I think my career trajectory really mirrors, I think Sheri and I have a lot of shared background, and I also just wanna say I echo what Scott says, that this work has to be done across these, these boundaries, if it's gonna be done in any way that we can impact it significantly. Just that as an exercise last night, as I was preparing, I, I decided, I'm gonna go back and see all the institutions that I've either went to or worked at, what their mission statements say about this notion of preparing citizens. And it's not surprising every single one of them has some language that directly references like that we're educating students to be citizens and, and constructive contributors and that kind of thing. So I just want to say that, I mean, that starts at the University of Wisconsin Stevens Point where I did my undergraduate work, the University of Michigan, the University of Southern Mississippi, where I first became a service learning director of shere, mentioned that, you know, in the eighties these things started popping up. I was part of that. I worked at the Wisconsin Campus Compact, which was kind of an association that worked across the country, but my, my purview was the state of Wisconsin looking at how do we actually emphasize the civic mission of, of the schools. And it was public, private, two year, four year faith-based, non-faith based, that, along with the experience of working at the institute, the, the college board in Mississippi gave me kind of a really broad lens of looking at institutions. I was tempted to say that most of my life I've been working in public higher ed, but that's actually not true anymore. About half of my career has been in public and for the last 14 years I've been at Stanford, which is, as Scott points out one of those weird institutions that, that I, that I think has something to contribute. I'll, I'll close by. I, I shared this anecdote with the group as we were meeting, but one of the funny things when I, you, you move from a place like the University of Wisconsin Parkside, a very like locally focused institution to Stanford. And it was within the span of a week where at the University of Wisconsin Parkside, the big issue that we were focused on as this three county community was how do we deal with the issue of truancy in our high schools, you know, across these three counties. Flash forward, I got in my U-Haul, I from, you know, Kenosha, Wisconsin to Palo Alto, California. The next week I was in a meeting and I'm having a conversation with people who are policymakers, researchers, academics, on how do we deal with the crisis of AIDS orphans on the continent of Africa. And I, I mention that because I think for a lot of people that's really sexy that the scale of that problem. But I, I come at this work never forgetting that the problem of truancy, you know, at the local level is every bit as important. And it's, it's actually what I think we're probably gonna dive into a little bit, that really great strength of many of the NSIs are these deep connections to their local community. Yeah.

- Thank you. Terrific. I want to remind everyone in the audience that we want to hear from you. So if you have a question either for the entire panel or to any individual member of the panel, now that you have a sense of who's, who's here, please put that question in the chat. We'll be picking out some questions and as we go forward, so very much wanting you and the audience to be part of this conversation. So let's talk about some of the unique challenges that are faced by those of you going to instruct in civics at NSIs, especially when compared to the potential of more well-resourced selective schools. What are, what are some of the really, you know, things that makes your work more difficult? And then, you know, how are you trying to overcome some of those difficulties?

- I, I can lead off again, if that's Sure, sure. Jump in. Oh, I mean, part of the reason I was attracted and willing to move to the current institution that I'm at is that the institute I direct is endowed. Every other place that I've ever been, I would spend, you know, get a part-time administrative appointment, do extra work above and beyond as service or, you know, develop curriculum or co-curricular experiences. It's not tied to the budget, it's not tied to a faculty line. We'd get a budget crisis or a new dean would come in and much of it would get gutted, right? And so here, I'm, I'm in the fortunate position where the institute is endowed and the things that I build will be permanent because I'm the one that decides how to pay for them. But, but that's classic, right? Like there's good intention and desire to do good things by a lot of faculty at MSIs. There's typically, like your dean will say, sure, go right ahead, do all the extra stuff, do all the extra service, burn yourself out. But there's typically not money for course releases or there's not money for, you know, to prop up institutes. I was at a convening this summer where the talk was about establishing centers or, or departments, standalone departments of civic studies in Ohio, we just passed legislation because of financial concerns and budgeting concerns that if you graduate fewer than five majors per year or 15 on average across three, the chancellor decides not your president, the chancellor in Columbus decides whether that department is cut. Well, those are my colleagues in, you know, philosophy might have a big role in the gen ed, but not have that many majors or history, right? And, and so how do we stand up a new department of Civic studies when we're letting go of the faculty with the kind of expertise that we need to teach to compliment the experiential learning? So yeah, the, the, the financial constraints and the time constraints for, for faculty at these kinds of institutions are, are serious and real

- For sure. Though I remember that my experience in Montana State that is that sort of odd trade off the people who are most engaged, who care the most end up taking most upon themselves. And then there is this burnout factor the, to just the, the, the exhaustion factor. And you can't keep it going, Scott. No, go ahead Sherry.

- I was just gonna say, and the, you know, the tenure requirements at non-selective institutions and regional publics, it's still publish or parish, right? So unless you can find a way to turn those service activities or that pedagogy work, I turned it into a research agenda. But, you know, the institutions themselves are not rewarding the work through the tenure and promotion process because they're looking up at the elite institutions where we all got our PhDs to set the standard for our research productivity instead of thinking about what makes the most sense for these kinds of institutions. So it's, it's a struggle for sure. Sorry. For sure.

- Yeah, Scott. Yeah, so I'd agree with, with everything that's already been said. And so I, I'll speak briefly about some of the challenges at, but I also wanna talk about some of the challenges for elite institutions because I think they're, they're just as important to this conversation. But just first on the University of Montana, I, I certainly agree that the biggest challenge is money, but I think it's, it's, it's kinda a little more complicated than that and similar to what, what she was mentioning, but at, we actually have quite a lot of funding for one-off events, like a recent lecture by Robert Putnam or great extracurricular activities like civic engagement, internships or service projects, because it's relatively easy to raise private funds for activities like this. And civic ed is a, genuinely a big priority for our administration. On the other hand though, we can't make long-term commitments that are necessary to replace retiring faculty in, in core disciplines like history or poli sci. And we certainly can't create new tenure lines focused on civic thought, for example. So this makes it difficult to do curricular work on a meaningful scale. And so we end up in this world where there's actually a lot of energy around these topics, but it's always channeled into things that aren't curricular and that aren't long-term. And to me, it seems like unless you have that, that long-term perspective to create something that we know is gonna last, it's something that it, it's tough to get that invested in. It's also tough to get students to commit to making a core part of their college experience rather than just say, oh, there's a cool lecture, I'll go to that one, but am I really gonna go to the next one? Because there's no degree program associated with it because it's not predictable. So again, I think short-term money is less of a problem. It's the long-term money, the long-term commitments that are the big problem, at least for us. I

- Do the one. Thanks. Go ahead.

- Oh, just maybe I'll let, I'll let Tom chime in, but, because I do wanna talk about the challenge for lead institutions as well, but I'll maybe let Tom speak on this first.

- There are no challenges, Scott, I don't know what you're talking about. No, happy to, happy to chime in there. It's funny, 'cause as I was thinking about this, it's almost like for every opportunity or benefit, there's also this sort of equal, an opport, you know, almost equal challenge that's associated with it. And I know we're already talking a lot about abundance or resources being abundant at a campus like this. And I don't want sound, I I I, I just need to preface this statement by saying like, there's a great benefit to having the resources, but I do wanna highlight some things that actually do end up becoming challenges, especially in the civic education or the citizenship space. One is, and Sheri you mentioned this sort of burgeoning, these centers that are dedicated centers. Actually, the center that I was at at the University of Wisconsin Parkside was not just the civic center actually was the, it was the continuing study center. It also was my, one of my hats was I was leading the continuing, sorry, the extension work for the campus. So there's this, what happens at Publix is you end up wearing a lot more hats than you might, and it would be dedicated. But the flip side of that is, is that when you have a dedicated center, it it's, it becomes possible. And this becomes kind of problematic at research intensive institutions where there is this published in Parish on steroids where it's like, oh, you're doing, you're doing civic stuff. There's a center over there. Just go do it over there. That's not my responsibility. And from my perspective, something like, and if you think about the mission statements of all of these institutions, it's everybody's responsibility. So it becomes too easy to abdicate and say, well, those are the specialists in this, so go work with them and I don't have to do this. That's, so that's one challenge with the abundance thing. There's also that a lot of the resources at places that are elite research intensive institutions, those research, those, those resources are directed towards the research and everybody knows it. And so there's a, there's, that is, that becomes a challenge. There's another form of abundance though, that at, at a place like Stanford, I just wanna point out, and that's, you know, I've never been at a place, I grew up on a farm in Wisconsin. I've never been at a place with this the same level of like ethnic diversity, you know, and people globally coming here. One of the challenges that that brings is that those students often come, they're very cosmopolitan. They come from way far away, but they don't have the rooted connectedness to the community that, that would natively or naturally happen at a place like a Parkside. And so they don't have the same connections to civic institutions. And I'll just cite two sort of examples here at, at Stanford, my best friends at the University of Wisconsin, Stevens Point, some of my best friends were actually involved in ROTC in the military, and they were gonna go on to military careers. Stanford hasn't had ROTC on campus at least since the, the early seventies. So like, there's not an exposure as much of an exposure to that sort of civic institution here at Stanford. The other thing, and Josh and Scott and I have talked a lot about this, is like the elites don't have as many people that are enrolling from rural places. It does not mirror what the, what the, what the country is. And so while there's great diversity, there's also, you know, and there's well-documented among the elites that there is less ideological diversity than at the publics or the NSIs among both the students and the faculty. So there, there are some challenges that I think that are very distinctive at, at, at the elites that I, I think, and this is why Scott and I have had lots of conversations about this, where it's really incumbent upon us to actually do a better job of connecting and collaborating across these boundaries.

- Yeah, absolutely. I think this is really interesting. Scott Sheree mentioned that one of the real tensions in NSIs is with a, you know, do you have a research career? Do you publish or risk perishing? You were just very recently promoted. Congratulations once again to, to associate professor with tenure.

- Not, not yet with tenure. I'm, I'm up for tenure this year, so,

- Okay, you're up for tenure this year. You're now, yeah, fingers crossed professor, but not quite. Okay, you're, you'll, you will now be, so that even more pointed then. Did you feel that tension? Did you feel that you were, in a sense getting pulled in two different directions? Either, you know, do your research, do what's necessary to, in a sense, get those publications out, or really dedicate yourself to the kind of teaching that I know that you are really wanted to do, helping students know, once again, become more effective citizens one way or another?

- Yeah, so it's definitely a tension. And I think this is something that many of my mentors both here and elsewhere mentioned was I, I was told very clearly don't do service. And I have very much ignored that advice. But it was something that I thought long and hard about. And part of the logic under underlying that is particular to my own situation. So, as you know, I know, I think Josh and Tom know my wife is a professor of American history at the University of Montana as well. And so we're the, the dual career couple who managed to find tenure track jobs in the same place, which in today's day and age is very, very fortunate. And so we've, we've always known that we'd be very unlikely to be able to move. 'cause trying to move anywhere is tough. Trying to move with two is even tougher. We also have a pretty close connection to this area. My wife's from Montana, you know, I'm from Wyoming, so kind of in, in the region. We have family in the area. And so we, we really wanna make this work. And part of our concern is that the University of Montana, like many non-selective public institutions, is in a place where it's long-term kind of survival as what we think of as the traditional research university. A place that values the humanities that values, you know, things like studying democracy and civic engagement is really under threat. And so what what we decided was that because we, we wanted to say we're gonna be here. And so that forced us to try to build programs to try to make the institution better. And you know, there's a way I could pitch this as being altruistic, but it's also very selfish. And because I don't want to be the last tenured professor in the humanities or social sciences at a once great institution, that's not an attractive thing to me to kind of be looking back on in 30 years. And so I wanna do things that will, will help build the institution. The thing is, it's, it's really hard. And I think, so I was fortunate to be in a place where my research was pretty secure, but, but the, but, but I worry for other colleagues, you know, kind of for future colleagues, a that they might face that choice and, and not be as lucky as I was. But two, my my biggest concern is that there might not be those future colleagues because all, we're really starting to talk about whether there are going to be any tenure track hires in, in, you know, these fields in the future. Hmm. And so there's a push at, and I suspect this is similar at other institutions to towards teaching faculty who will teach very high, and in my opinion, unconsciously high loads. And they might not have any research expectations, but they will have trained, will have gone to this career thinking of research as a core component of their professional identities. And so I think that's going to be, be really difficult for people. So again, I, I'm facing, I I face that, but bizarrely, my concern is that other people won't even get the cha get the chance to face that, that tension because they won't have a research capacity. And, and again, I'm hoping that's not the case, but it's something I'm increasingly afraid of.

- And can I just piggyback on that and say the, the concern that it, in addition, right, to, to thinking about treating people at my kind of institution as second class scholars, right? Who, who aren't worthy of producing research is there's all kinds of insights about the different kinds of students that attend our institutions that you will not have if we're not doing the research about what works. You know, I have unique students. We have a huge new immigrant base in Akron. We have, our students are not ideologically as polarized. We have a much more mixed campus. How do you, how do you teach at these kinds of institutions? I spent, you know, 15 years at a rural, in a rural place where, where the approach was much different. And I think it's ironic that, that we're gutting these kinds of institutions of the ability to serve our students, in part because we serve the bulk of the, like, if you want good citizens, you've gotta come to us because this is where students are going to school. But also our students are much more interested in public service, right? There was a report that came outta the Manhattan Institute. 60% of the civic and political leaders at the state level are at, you know, either like an OSU or a a, a state prominent state school, like OSU or Michigan State, but also at places like the University of Akron. Think about that at the local level. Where do your mayors go to school? Where do your city council and school board and all the people that make democracy work in a federated system as big as the United States? They're in my institutions. My students want to run for office. I have a student who just bought a house in the ward where he wants to run for city council. I have, I have students in every mayor's office around every suburb in the city of Akron. I have students who are the executive directors of the local county parties in Bo on both sides, right? So, so my students see that kind of service and those kinds of careers as where they're headed and what's rewarding. And, and I don't have to persuade them to do it. They come to me. Our, our numbers for the political science major are robust. And so unlike, you know, Stanford where you've gotta persuade them not to go into finance or not to go into management consultant, where they'll become much more wealthy. You know, my kind of students want this, this experience in this work, and yet we're cutting off the ability to serve them, which is, which is a little scary.

- Can I, can I jump in there please, Tom? Yeah, let me, let me try to complicate that a little bit because the, first of all, agree with you a hundred percent Cher, but want to add a little bit more nuance to that? So I served as the executive director of the Haas Center for 13 years. And it, it's funny 'cause I kind of had rose colored glasses

- On. You wanna explain what the Haas center center is?

- Sorry. Yeah. The ha the Haas Center for Public Service is the, the, well, the center I was describing that, that stood as like this, oh, we are going to get students involved in public service and encourage them into careers in public service. They did a lot with faculty around service learning and community engaged research. So it, it was interesting 'cause my glasses were sort of rose colored about like who was coming to Stanford. 'cause the students that were walking through our door were the students that are sound very similar to what the University of Akron students were. Our big challenge was, frankly, seeing so many of those students who would be kind of fear of missing out by their sophomore year because the students, their, their colleagues, their peers were getting these really cherry offers from management consulting firms, from finance firms their sophomore year in college. And so it's like, oh, even though I wanted to go on and I, I thought about going into elected office, or I wanted to be a a teacher or that kind of thing. There's so much of that pressure. So I, and I do think that that's actually a very big challenge at elite institutions because that's, those, those firms are all targeting campuses and they know, they know the deal that they, they can, they can get to those students early then, then that, that becomes a, a, a very easy path for them. And, and so a lot of the work is to kind of convince them. The other piece of that is to convince them that it's not just jobs with the World Bank or at the federal level, you know, like these kind of massive national or international jobs. But that the actual really interesting work in some cases on the civic level is at the municipal or at the county level. And so a lot of students, that, that was a big part of our job was to try to expose them to that and in hopes that we could continue to convince them that this is a viable career path for you.

- I'd like to pick up on just a couple things that, that Tom and Cher said. So the first one is just talking about the differences between students at non-selective institutions and elite institutions. And this, I think is, is really important because the, the problems, the challenges are different, right? On the one hand, it's trying to persuade people, no, you could have a career in local government, you could run for city council, you could do these things. And the other challenge is no running for mayor of your hometown isn't beneath you. And that really is a, a problem at a, at a place like Stanford, the idea of, oh, you're just a mayor. That's, you know, like, and so I I think that like, those are fundamentally different challenges. And this is one of my concerns about the central role that elite institutions have played in designing civic ed, is that civic ed designed at Stanford for Stanford students, if it's then disseminated, adopted by other places, it'll attack the wrong problem. And so I think that, that, that's one of the reasons why we need partnerships. We need to lay central, non-selective institutions because is because the, the, the curriculum will look different. The second thing I wanna talk about is, is why research matters. So Shari kind of touched on this, but Right, so I think, right, there are fields, you know, maybe I just don't know enough about astrophysics, but I'm, I'm gonna pick astrophysics where doing research, fundamental research at a place like Stanford or MIT or things like this, that totally makes sense. It doesn't really matter that you're in the ivory tower because you're doing astrophysics. Civic education of any field is the field that is least possible to do well in the ivory tower because by its very nature, it has to engage with the civic body, it has to engage with local government, with like, you know, local refugee resettlement groups with local homeless shelters, with things like this. And so it's just, it's just not well suited to be done well in ivory tower kind of institutions. And so this is why a, as I've said, you know, I think that civic education and civic research, and that's the other point, is that we need people who are doing the research to be at these institutions. We can't just have the, the teachers there and the great researchers at Princeton or Yale will design the curriculum. So we need the researchers and the curriculum designed to be at these institutions as well. But the second thing is, insofar as people at elite institutions want to do this, they need to find ways to get out of the bubble and to go to Akron, to go to Missoula and to spend serious time in these places so they can learn what's going on, on the ground. And this is one of the reasons that I think partnerships are, are so vital, not just for institutions like mine, but also for these elite institutions.

- Terrific. Well, I wanna remind the, the audience, we'd love to have your questions. We already have some coming in, but we'll turn to questions in just a few minutes. So please do plug in your questions if you, if you have them. I thought we, maybe we little talk a little bit more about collaboration. We have some idea about, you know, the challenges that you're facing in NSIs, but also about some real advantages that you have that simply aren't shared by most elite institutions anyway. Are there ways in which we could effectively come together to learn from each other and to help one another in actually, you know, really practical, actionable kind of ways? I mean, after all, the alliance for civics in the academy is meant as a community of practice in which we learn from one another, but it's also meant to be a center for finding new ways of working together, working across institutions as well as what we do within institutions. So how might, you know, selective and non-selective institutions work together to accomplish some things in the civics domain that would be difficult or maybe even impossible if we stay in our own bubbles and we stay in our own, in our own worlds. Yeah. So Cherie, you want to, you know, jump off on

- This? Yeah, sure. I, well I think one of the things is, is helping, you know, we at the, at the non-selective institutions are sometimes our own worst enemy about our tenure and promotion standards because we absorb what we think is a successful career while we're in training at the elite institutions, right? Where we all get our PhDs and then we hold each other accountable for that. I mean, I think political sciences kind of had a sea change recently. There's a report out about teaching for Democratic capacity and I think people are taking it seriously. But for a long time even I was at a teaching institution and I had colleagues that would say, you know, we don't wanna count. This should count toward teaching excellence. You know, if you've done a multi-campus, you know, experimental design, you know, assessing some sort of pedagogy, they wanna count it as teaching excellence and not research. We need help shaping graduate students who were gonna hire to understand and value this work. And, you know, the serious effort to collect data, the serious effort. I was fortunate to be at a place when I was going up for tenure and then going up for full where any peer reviewed outlet was prima fesh evidence of a category one publication. So I forced 'em to count my, my work that was assessing, right, teaching seriously. But that's not the case for everyone. So helping the grad students who you're socializing that success doesn't have to just look like a career at Stanford, right? Like we value what you produce when it's right, when it's about these other, right. More, more centered sort of applied fields. And then the other thing is, one of the things that I've tried to do is to help create the, create those public out publication outlets for other people. So I was on the editorial team for the Journal of Political Science Education for six years, where I made sure we had calls and had good reviewers for civic engagement work that wasn't just about political science, disciplinary work. I've published in a series of edited collections that apps have published on teaching for civic engagement. There's a fourth book coming out. You know, that those book chapters can be filled, especially if they're anchored or have chapters in it by people from elite institutions. So you can take it back and make those arguments help us, right? Help us make the case that this work should be taken seriously and can be a research agenda.

- Terrific. Tom Scott, I know that you've both worked in some cases together on trying to think about, you know, how might we have a pilot that would actually get lead institutions and non-selective institutions working together, even getting students to move back and forth. Could tell us a a little bit about those plans, either or both

- To, do you wanna talk about the three P fellowships and then I can follow that up or, sure,

- Yeah. Let me, let me actually start by, I wanna reference something that I, I think is actually a really a big responsibility for people in elite or well-resourced institutions. Because as I mentioned, I spent half of my career kind of looking at those institutions and kind of saying, oh, they've developed this research model, or they've developed this thing where they often have the, the resources of the time to do that. When I came here to Stanford, I basically led this initiative to try to develop this thing called the Pathways of Public Service and Civic Engagement. And we created this diagnostic tool. But very early on I said, I, I don't wanna do this by myself. I wanna actually have a bunch of institutions. So I partnered with a bunch of people, most notably this guy Sean Crossland, who was at Salt Lake City Community College, who, who really helped us kind of make sure that the tool we were developing didn't have all that language that like elites would put in it that would be kind of accessible to both people in a community college setting as well as a place like Stanford. I, I have to, I'm, I'm really proud of him 'cause he basically for years kind of looked at that data. We, we had actually had access to the data and he recently just published a book. He's now at Utah Valley University. Tomorrow he's having a webinar where he is launching this, you know, book called Pathways to Social Impact Higher Ed for the Public Good that's gonna be with Campus Compact. So I, I think that there's a responsibility that people have when they have the resources to make sure that there's people that are drawn in. The same thing is true of this civic profile, this Myers-Briggs and sort of instrument that we're developing. Josh is a part of this working group on American citizenship and civics that we wanna make sure that anybody can use this tool actually high school or above right now, but it'll be online. And so making those resources available, but also to the faculty who are at other institutions to say, you can use this data. That's the important part of that. So, and but moving to this people politics and places fellowship, which is what Josh is referencing, and I'm gonna turn it over to you, Scott, 'cause I want you to kind of lean into some of your ideas, which are, are I think are really fascinating. So one of the things that we recognized at Stanford is, I, I mentioned this lack of rural exposure to many of our students. We, we actually developed a pilot last year we're, we're continuing at this year where we actually select a group of Stanford students in part based on their lack of exposure and work with them for a year to sort of explore this geopolitical divide. And then we've chosen several partners across the country in Alaska, in Wisconsin and California, and now in Montana. And so we're gonna be working with, with Scott on, on this, and I'm gonna turn it over to you, Scott. 'cause I think kind of what your plans around this are, are really fascinating and it's also a model of how this kind of interaction can play out and even, you know, in the future. So Scott, you want to talk a little bit about what your plan?

- Absolutely. So as Tom mentioned, we're in the initial stages of a collaborative project that will, you know, kind of take place between Stanford and the University of Montana. And so for the first stage of this, we have a two week residential civics program for Montana High school students that will be housed at the Mansfield Institute, you know, at the University of Montana. And I'll teach it for the first time in July with a team of two students from, and two students from Stanford. The Stanford students will join as part of that fellowship that Tom mentioned. And then after the institute, they'll spend about six weeks working with one of our local partners, you know, on projects that are designed to engage them in, in the civic aspects of rural life. And so next year we're then hoping to both scale the summer program and potentially the, the fellowships for the Stanford students as well. But we also want to kinda expand this partnership. So we're exploring the possibility of hosting a Stanford faculty member, or more likely a Hoover fellow at, hopefully from my perspective, in exchange for teaching a course in our democracy studies program. And then we also are hoping to recruit some Stanford participants for our third annual Democracy Summit Summit, which brings local elected officials and civic leaders to campus for conversations, experiential sessions on a chosen topic related to democracy and civic life. And I think the cool thing about this, right, is these are, these are the local elected officials, the types of people that, you know, a lot of the Stanford kind of people who are interested in this, they're gonna be more comfortable and more experienced in dealing with people from the World Bank or the federal level rather than local elected officials. So I think it would be an interesting experience for them. So despite the financial challenges that I've already mentioned, we either have or are confident in our ability to secure funding for these initial steps. And the hope is that once we've demonstrated the potential of this partnership, we'll be able to raise the funds that will be necessary to extend it. And so ultimately, right, if all goes well, we'd like to have more faculty exchanges, something like a shared postdoc in civic ed, parallel classes with joint meetings, student exchanges, collaborative research projects. I think there's a ton of potential here. But of course, as with everything we have to demonstrate proof of concept. And so I think we're at least moving pretty well in, in that direction.

- Well this is really, I mean this, this is hopeful. I mean this is, it's it's easy to become depressed about the potential for, you know, losing faculty under understaffing and so on. But this is what we're, we're hoping is that we begin to imagine ways forward that we can work together. I wanna take a couple of questions now from our audience. The first one is, and I'm quoting here, it seems to me that a central issue about education that surrounds civics, especially at NSIs is the loss of support for the humanities and related liberal arts history, political science, for example, in favor of other fields. Can we meaningfully increase civics without a national rehabilitation of the liberal arts as meaningful and worthwhile?

- I'd be happy to take a first stab at this just because this is something that's very dear to my hearts, to my heart, and really the, the I, so I think that the liberal arts and the humanities really need to be central to, to civic education. And so I don't think that we can really do this without a revival of that, but I think that an increased interest in civics and a revival of civics can also be a means to the end of reviving the humanities and, and the liberal arts. So I think that I don't, I I I think again, a lot of my interest in civic education is my interest in the humanities because I do think that the humanities are, are an integral part, you know, both historically and, you know, just to me found on a practical level of, of this overall project, the one thing I'd say is that I can all, I can imagine a world where you have things like a school of civic thought or something like this that would have humanists there who would be core, you know, parts of those faculty, but who might not necessarily be housed in a traditional English department or something like that. So I, I think that, you know, we certainly need to have humanists, we need to have these, these liberal arts perspectives, but I'm not 100% committed, even though it seems more natural to me that it would look like the same administrative setup that we currently have. Yeah,

- You have you from a political science perspective,

- Yeah, much of the, much of the way that like, so the, the civic engagement movement, you know, that, that started with service learning and spread out and, and has, has sort of had traction and, and roots. It was built on the assumption that the knowledge would be taught through the gen ed, right? That those courses would exist, that your students would be required to take Western civ, that your students would be required to be exposed to, you know, whether they took a, a straight up class in political theory that they would at least be exposed to some of the, the ideas of the enlightenment, either through an English or a, a history or, you know, some sort of western civ sort of class. And so yeah, we're grappling with that now. Like how do we, you know, how do we continue to make sure that, you know, the, the experiential learning is focused on cultivating, i I do a lot of deliberative work. You know, the experiential learning is focused on cultivating the intrinsic identity and disposition, but also the skillset. How do we make sure that we are backfilling and ensuring that our students have civic knowledge when, you know, we haven't cut them yet at Akron, but I, I feel like some of those programs might be under threat. So I, I don't know, I don't know quite what that looks like going forward, but it's certainly something that we need to tackle

- For sure. There's another's just, oh, go ahead Tom.

- No, I'll just say briefly, I think the answer to the question of like whether you can do this at the national level without a revitalizing of the liberal arts is no. I mean, you can't do that. Like, no, but I, I want, I want to back out one level to that and say, I, I think the other thing, and, and Sheree mentioned this before, there's this like tension of everybody wanting to model themselves after the Harvard, the Stanford, the Yale, whatever. I think until we get to a point where people are comfortable and we can break away from that sort of institutional isomorphic kind of tendency, there's a, there's a whole burgeoning movement out there of micro colleges that are doing really amazing things around civics, you know, places like the Royal College or pipelines or Sland Institute in these really rural places. And I think that we have to be open and I don't know quite how to crack this nut. How do we actually open ourselves up to that? There is more than one model of way of being in higher ed and be comfortable with that, both as individual faculty, but also as sort of a network of institutions.

- If I can say one more thing just on the humanities specific question, just a, a plug for the a CAI don't know if the person who asked this is a, an a CA member, but I would certainly encourage you to do this if, if you're interested in the humanities and the relationship to civic ed at one of our first meetings, Peter Levine, who goes to lots of these civic focused meetings kind of told us, and it was a real aha moment. It's like, oh, you're the humanities group that does civic ed. You know, I go to lots of these things. This is, this is the kind of the people who think the humanities should be central. So I think that's certainly a shared belief that that many of us have.

- Right. Well, here's another question. This is about mentoring relationships, good mentoring relationships between more senior faculty at more selective institutions and junior faculty at less elective institutions, be a way to help legitimize and support the civics teaching and service research that these junior faculty are trying to pursue, either to help them get tenure or advance their career in the directions that they wish is

- There, I guess depends on what kind of advice they're gonna give. If, I mean, the advice that I've typically gotten from people at research intensive, right? Elite institutions as, especially when I was in my PhD program, was to not do any of this work and to publish a book. So if that's the advice they're gonna give, no, but if it's Josh, maybe, you know, maybe that's okay. I really, the people that provided the most support for me and helped me craft a career where I could dedicate a substantial portion of time to this where people who already had, had tenure at similar kinds of institutions because they understood here's how to make the argument. And I write all kinds of tenure letters now for people because they get sent to me because people know, I will say, Sol Research Scholarship of Teaching and Learning should be t that is a serious research publication, right? That should be taken seriously. And they know that, I'll say that in the letter. And so the people that helped me craft how to make the arguments that would be persuasive or, you know, recognizing that political sciences overwhelmingly quantitative. And if you want people to take this seriously, you have to build multi-campus data collection, right? Like you have to invest the time in, in cultivating the relationships to do multi-campus so that you can, you know, get a, a publication that's not a book chapter in your field. And so the people, but the people who were most helpful to me were people at similarly situated institutions with similarly situated value systems. But that's not to say that, you know, that we couldn't right. Have collaboration as long as people understand the different tensions that exist in the, you know, the way to build your tenure case at an NSI.

- Terrific. Well, this is just exactly the reason that we need, you know, resources coming from people at NSIs to help other people at NSIs think about, you know, how do you, how do you move through a career? How do you, who do you get advice from? We have one more question, we have several, but I'll try to try to choose one of these. What are some practical strategies for encouraging students at elite institutions to pursue careers in public service, especially at the local level? And what's the role of the overall campus culture given how polarized our, our politics are? Why would a student want to get involved in running for an elective office? Tom, I know you've thought a lot about this one.

- Yeah, the, well, the practical strategies I think are kind of bound up in the, essentially some of the either research opport, sorry, internship opportunities that you can provide students very early on and some of the mentoring that that can happen. And, you know, it, it coincides with going back to the abundance thing, the, the resources that a place like Stanford can have, they can actually dev, they can vast resources to say, we're gonna support students who are interested in this or to spark that interest. There's a group at Stanford called Stanford and Government. This is a student led group, and they basically started this program that was like a, if you're a first year student or a second year student and have any interest in public policy, we're gonna give you an, some resources to go do an internship. Now the, the, the what's incumbent upon the people organizing that is making sure that all of those internships aren't basically in Washington DC or Sacramento, that they also exist. Like, hey, you're gonna go to, you know, Santa Clara or Bakersfield or wherever and that, so that's one practical way of kind of doing that. Scott mentioned speakers too, like there was a, a speaker program that we created that was basically local electeds that would be in residence for a few days and they'd sit in, in our, they'd have an office and meet with students talking about like, Hey, yeah, you can go and work in DC but if you really wanna see the impact of your work and, and policy do it at the municipal or the county level and they can give the students the kind of real life, this is what I was able to accomplish. So that's, that's that. What was the second part of that question, Josh?

- Oh, just given how polarized our politics are, why would anyone want to get involved? But that's, maybe that's just an impossible question to answer.

- It's, it's, it's, I i I, I don't know why, but I do why people would get involved. But I think that the why for me, the more important why is that's why we do this work. Like we have to do this work in a way that, you know, and, and I, I think the example, and I I I take Scott's point about not just porting out what's done at Stanford or Yale or whatever, but that college 1 0 2 course, Josh, that I know you had a really big part in creating the, the, the, the citizenship in the 21st century where they spend a lot of time, I'm teaching it this quarter, we spend a lot of time in the very beginning talking about why disagreement is important, how you do it. Well you know, what, what is the point that John Stewart Mill would say, why do we have free expression? Why is, and it's interesting how few students actually get exposed to that before they come here. And so I think I, it's not maybe the, the answer to why that the audience member was looking for, but I think the why, it's the, the why we do this. So that's, that's so important.

- Ironically, I, I have research findings from my multi-campus scholarship of teaching and learning that shows one of the things that can increase willingness to be involved in politics is exposure to, to civil discourse. Whether that even just video clips of, of political actors like trying to solve a problem across partisan divide or ideological divide where they're, where they're not name calling and being rude, whether it's on a debate stage or at the local level, just a series of clips. But then when you involve them either in like real deliberative work on campus to solve a campus problem or with the, we have an initiative right now with Unify America that's doing a citizens deliberative assembly in Akron with Akron when they, when they see the possibility of what can be accomplished through right, using right free speech to be civil and engage even when you disagree, then like their eyes widen and they, they haven't been exposed to that enough. And then they're much more willing to think about, you know, political science as a major or running for office as a career. They just don't have enough role models. So there are lots of really tangible, simple things that we can do, and it helps when you've assessed it and know that it's a best practice and that it actually works. It helps when you go to your dean or your president and go, here's the data. This will actually work.

- Terrific. Well, we had other questions that I wish we had a chance to get to, but I want to just wrap up by thanking Sheri Tom Scott for certainly was a conversation I learned a lot from, and I'd like to reiterate our hope that you and the audience will want to get involved with the Alliance for Civics in the academy. This is a shared endeavor. There are, as we've already seen here, many approaches to determining how to provide the best knowledge, skills, dispositions, and experiences, essential for effective citizenship in the 21st century. The American Eco. You know, the American Academy is a diverse ecology of teaching, of learning and research, and we need to make the most of that. Our community of practice will be most valuable when we share ideas and resources from across the full spectrum of higher education, public, private, red and blue, big and small, well and poorly resourced. So please do join us if you're not yet a member. Send us your resources, send us your ideas. Let us know how we might be able to help you best. The relevant websites, once again are available in the chat. And finally join us for the next episode in our webinar series, which is going to be on February 18th. At the same time, we'll be talking about new and effective approaches to civics pedagogy and how these could be adapted at a wide range of institutions. Once again, let me just reiterate my thanks to our terrific panel and we'll be looking forward to seeing all of you on February 18th and for the continuing series in this, in this webinar. Thanks again.

- Thank you. Thank

- You.

- Thank you.

ABOUT THE SPEAKERS

Thomas (Tom) Schnaubelt, PhD, is the Executive Director of the Center for Revitalizing American Institutions at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. Tom came to Stanford in 2009 and served as an Associate Vice Provost for Education and Executive Director of the Haas Center for Public Service for 13 years while also serving as a resident fellow in Branner Hall, Stanford’s public service and civic engagement theme dorm. Prior to Stanford, Tom served as Dean for Community Engagement & Civic Learning at the University of Wisconsin-Parkside, launched and directed Wisconsin Campus Compact, and led several national service and service-learning programs in Mississippi. He earned a PhD from the University of Mississippi, MA from the University of Michigan, and a BS from the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point.

Scott Lawin Arcenas is a historian and classicist who specializes in the history of democracy and political violence. His first book, Political Violence in Ancient Greece: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches to Stasis, 500-301 BCE (forthcoming, Cambridge University Press) examines the nature, frequency, and intensity of political violence in fifth- and fourth-century Greek city-states. It also introduces new methods and tools to overcome three of the most significant obstacles that confront attempts to study Greek history on a panhellenic scale: the scarcity, ambiguity, and deep biases of the evidentiary record. In recent years, Professor Arcenas has published articles on travel and transportation in the ancient world, digital history, Roman numismatics, Thucydides, and digital pedagogy. At the moment, he is working on three research projects: an introduction to Athenian democracy for The Basics (Routledge), a monograph on epistemic uncertainty in narrative histories of Greek city-states, and a series of articles on the relationship between political violence and the Greek economy.

At the University of Montana, Professor Arcenas teaches courses on Greek history, Roman history, Latin, Greek, the history of democracy, and citizenship in both the ancient and the modern world. He is a passionate advocate of civic education and General Education curricula--both at the University of Montana and elsewhere. Before arriving at UM, he taught at Stanford University, Dartmouth College, and George Mason University.

J. Cherie Strachan is Professor of Political Science and Director of the Ray C. Bliss Institute of Applied Politics. Her political science research combines interests in political participation, voluntary civic and political organizations, and political communication. Recent work explores the #MeToo movement and women’s political ambition, as well as the effects of partisan polarization, rudeness, and civility on political engagement. Her applied civic engagement pedagogy research focuses on facilitating student-led deliberative discussions sessions and on enhancing the political socialization that occurs within campus student organizations. Strachan is also co-author of the textbook Why Don’t Women Rule the World? and co-editor of the APSA-published resource Strategies for Navigating Graduate School and Beyond.

Moderator

Josiah Ober is the Constantine Mitsotakis Chair in the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford University, Senior Fellow of the Hoover Institution, and Founding Director of the Stanford Civics Initiative. His primary university appointment is in Political Science; he holds a secondary appointment in Classics and a courtesy appointment in Philosophy. His most recent books are Demopolis: Democracy before liberalism (2017), The Greeks and the Rational: The discovery of practical reason (2022), and The Civic Bargain: How democracy survives (2023, with Brook Manville).