The Hoover Institution Library & Archives has recently acquired the papers of Herbert H.D. Peirce, which range between 1882–1916.

During the early years of the First World War, when the United States was not yet directly involved in combat on the side of the Allies, its neutral stance allowed it to engage in various humanitarian projects, such as the Commission for the Relief of Belgium, led by Herbert Hoover. Hoover’s namesake, Herbert H. D. Peirce, was an American diplomat appointed Minister Plenipotentiary in 1915 to assist Ambassador David Francis in Russia with special missions, like those relating to the interests of the Central Powers in Russia, such as examining the conditions in prisoner of war camps. This collection of his papers consists almost exclusively of documents relating to Peirce's studies of conditions in the camps and among German and Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war (POWs) in 1916.

Peirce was considered something of an expert on Russia. As a Harvard graduate, he had served in Russia at least since 1894, achieving the rank of first secretary of the U.S. Embassy in Petrograd by 1899. In 1902, he published an article on the country for the Atlantic Monthly. As third assistant secretary of state he greeted the Russian delegation arriving in the United States on August 5, 1905, for peace talks with the Japanese at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to end the Russo-Japanese War.

Most of the documentation consists of reports and correspondence from Peirce's travels to Siberia and the Russian Far East where he investigated conditions in the camps. It also includes a note of special permission allowing him to transport a crate of Italian vermouth and two crates of whiskey for Ambassador Francis. (Interestingly by comparison, the naval attaché, Captain Newton A. McCully, was to receive even more: a crate each of whiskey, gin, and vermouth and two crates of champagne. Among the reports is a detailed description of conditions in Krasnoiarsk, located deep in Siberia, where POWs suffered from an epidemic of spotted typhus and needed medical and other supplies. Other reports describe conditions at camps in areas of Siberia and the Russian Far East: Omsk, Kurgan, Irkutsk, Chita and Khabarovsk. There are also several letters and petitions from the prisoners themselves detailing their needs and complaints.

One of the most interesting documents is a letter dated September 1915 written while in Finland which describes the overall conditions in Russia, including the first signs of bread shortages in the capital, Petrograd (it was these shortages that provided the spark for the revolution on 1917). The author is unidentified, as the final page(s) is missing, but likely it is Peirce himself, who wrote about finding fault with the transportation system rather than the harvest as “for some days our morning rolls had been becoming small by degrees”. Ultimately, the author concludes that Russia would be better off if it put the POWs to work building railways and roads, “as she might well do under the provisions of the Hague Convention? A few, it is true, are employed upon the needs of the railway. But these are but a very few. The great bulk of the prisoners loaf idly about the camps, in absolute indolence, well fed in their abundant leisure…”.

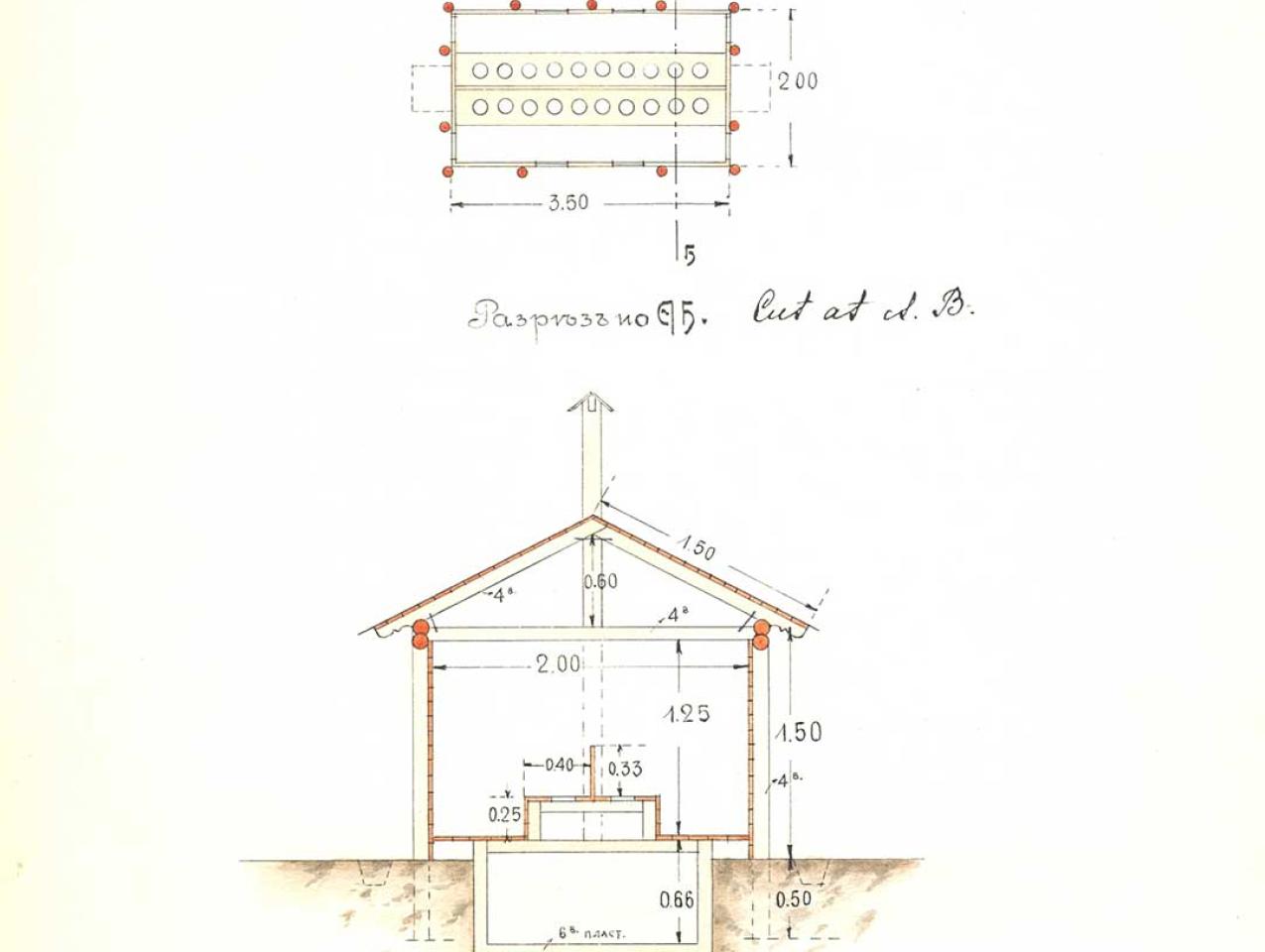

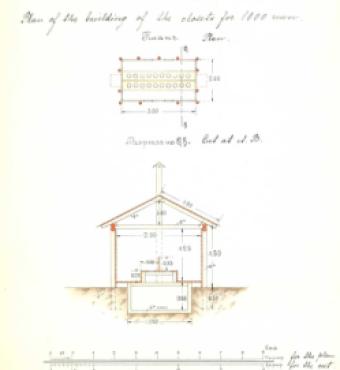

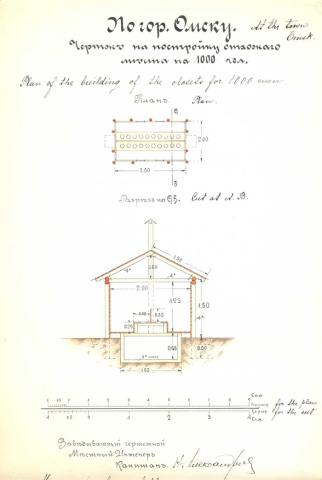

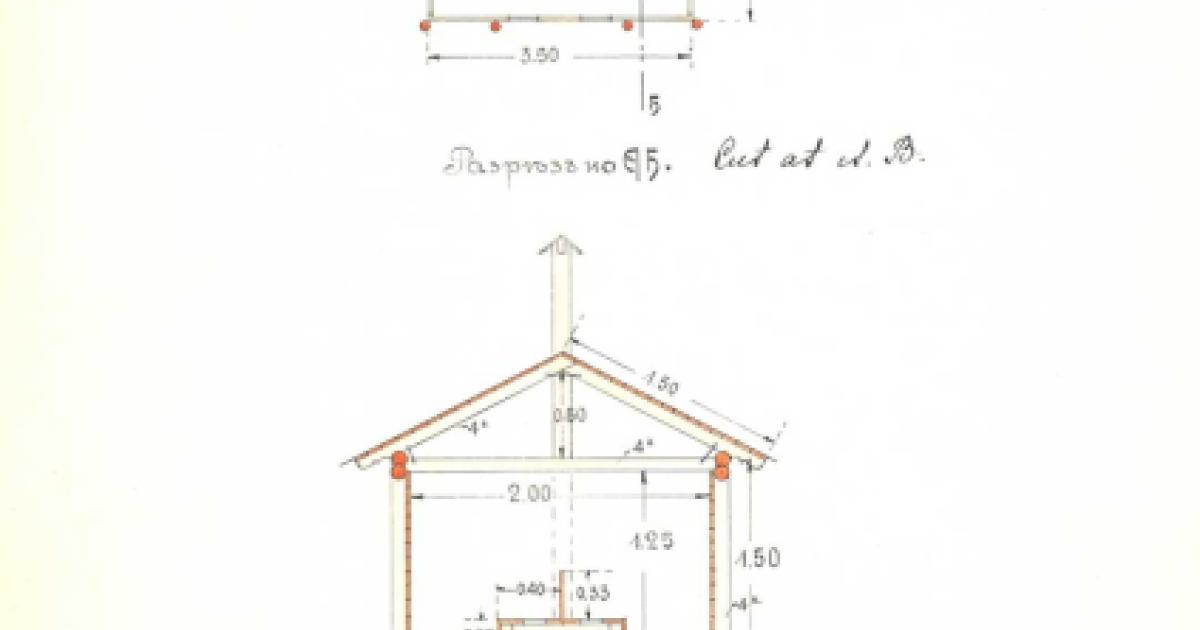

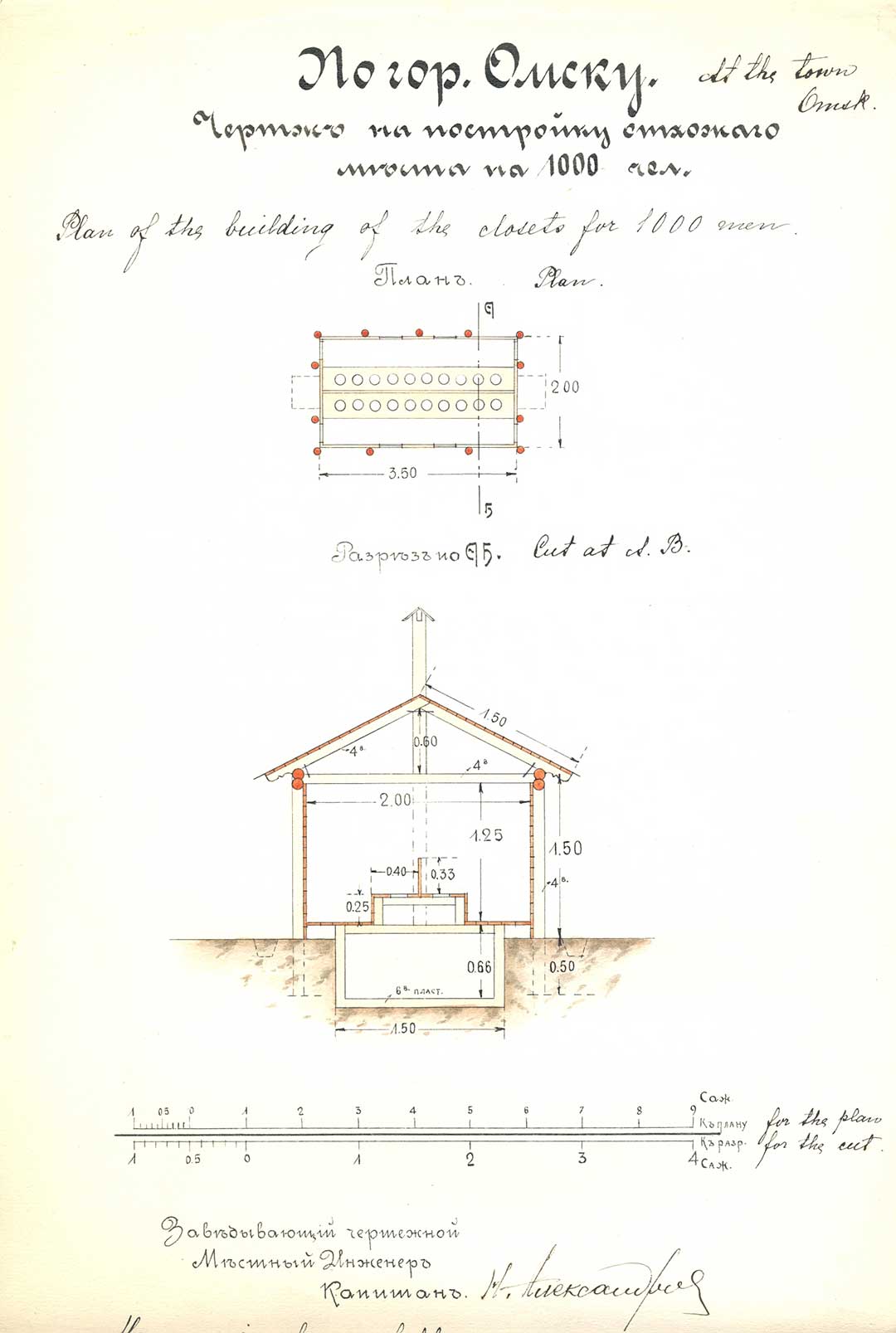

Also present in this collection is a series of architectural plans for POW camp buildings, such as the outhouse pictured here, designed for the needs of one thousand men, and a German-issued map of POW and civilian camps across the Russian Empire as of 1915.