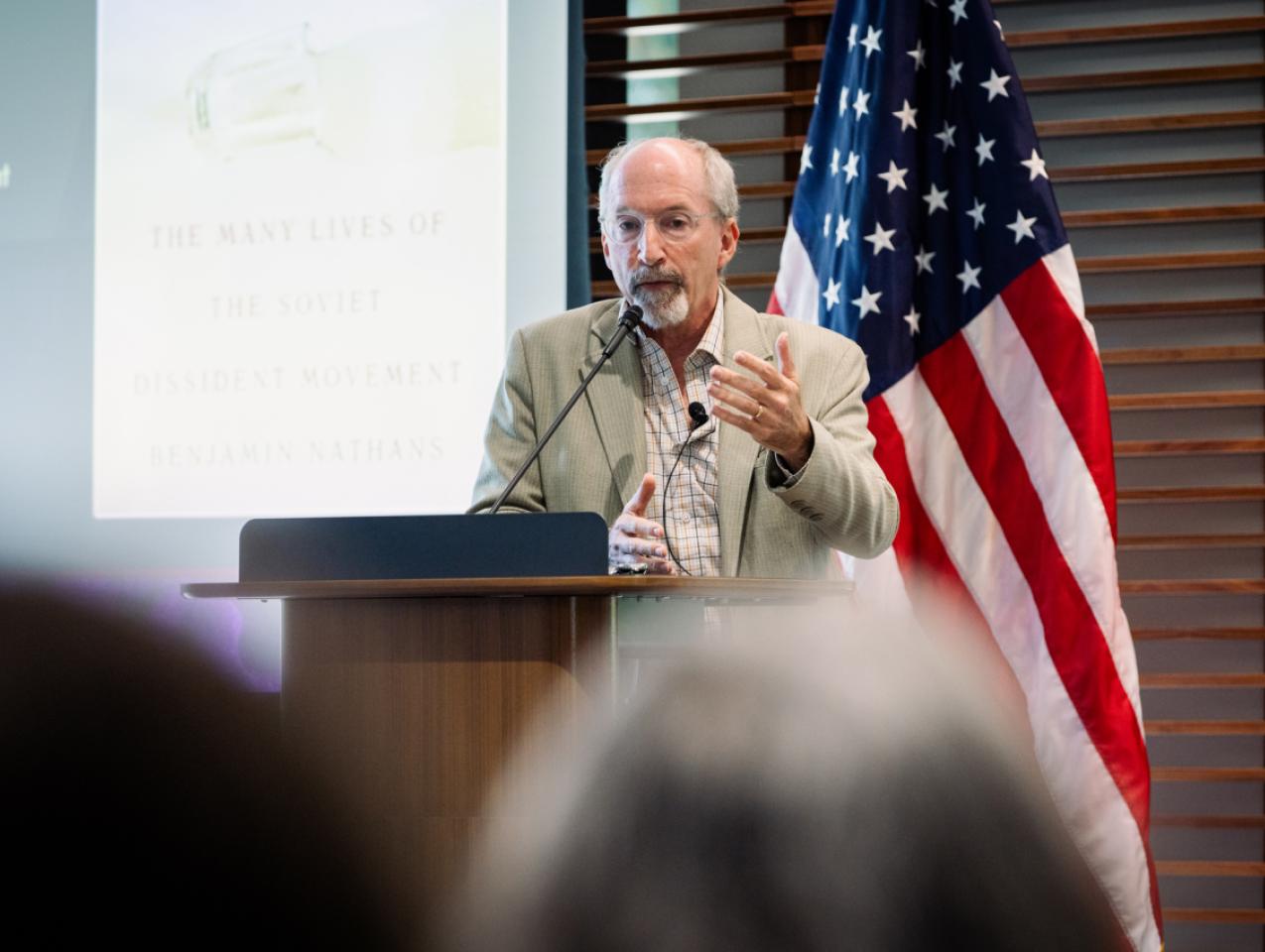

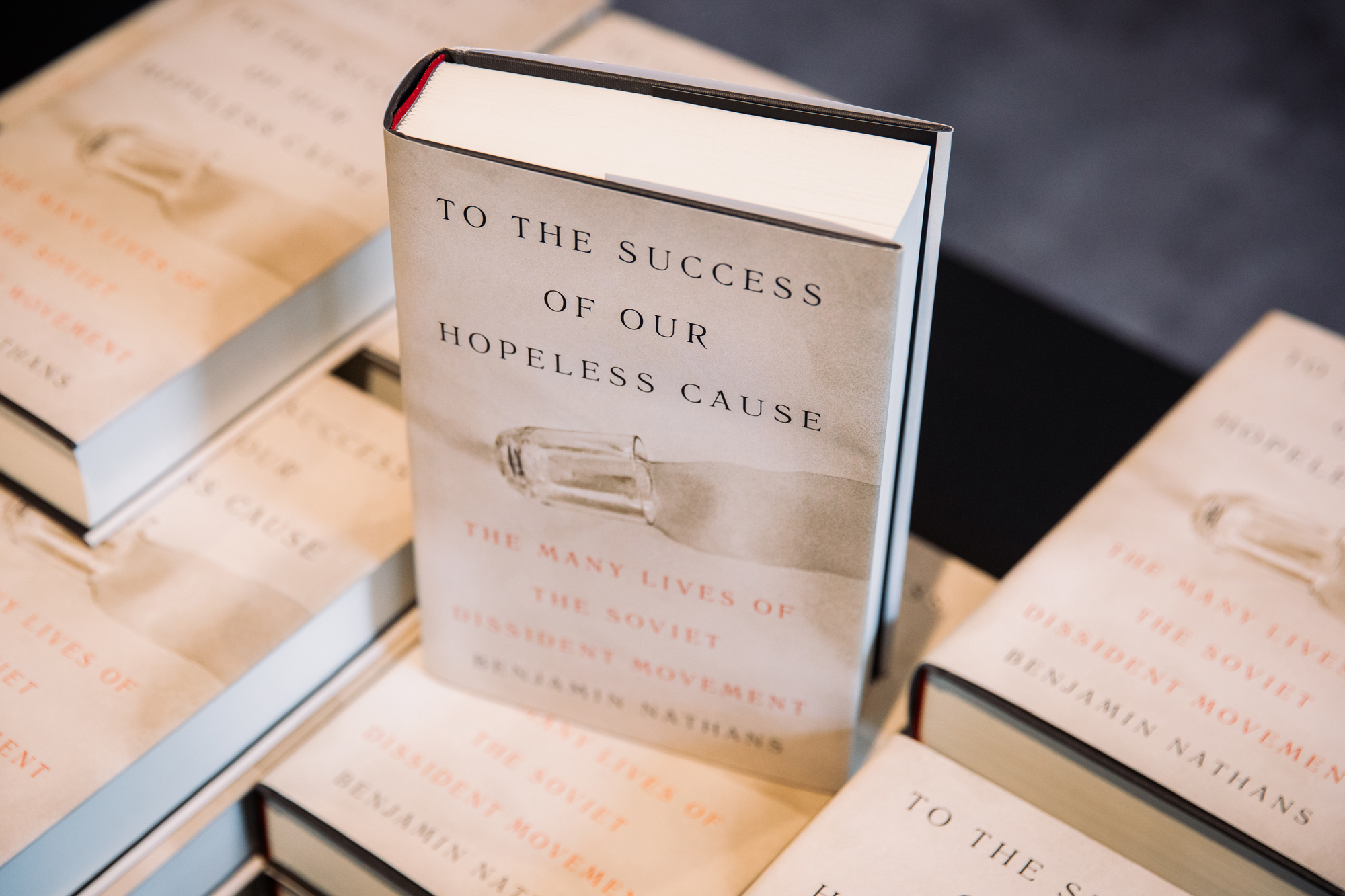

Hoover Institution (Stanford, CA)—A book on Soviet dissidents that draws heavily on records housed at Hoover’s Library & Archives detailing the absurdities of Soviet times has won the 2025 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction.

Its author, Benjamin Nathans, professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania, says putting together To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause: The Many Lives of the Soviet Dissident Movement became possible once he got access to the treasure trove of Soviet records stored and preserved at Hoover’s Library & Archives.

“It wasn't just like being a kid and walking into a candy store. It was like walking into a candy store where everything is arranged alphabetically,” Nathans said.

The Pulitzer Prize Board called the book “a prodigiously researched and revealing history of Soviet dissent, how it was repeatedly put down and came to life again, populated by a sprawling cast of courageous people dedicated to fighting for threatened freedoms and hard-earned rights.”

Stories of Soviet Dissidents Housed at Hoover

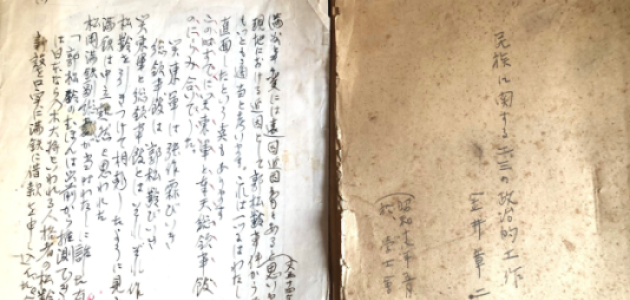

At Hoover, Nathans said he came across voluminous materials by and about the Soviet writer Andrei Sinyavsky. Under the pseudonym Abram Tertz, Sinyavsky published a series of works that satirized the Soviet regime and were published abroad.

At the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Sinyavsky was able to request his personal dossier from the KGB.

“It’s multiple volumes (long),” Nathans said. “When he died, his widow sold the collection to Hoover.”

Sinyavsky and another writer were criminally prosecuted by the Soviets in 1965–66, in what became the first Soviet trial where writers were tried solely for the contents of their works published abroad.

“It is just a historian's dream,” Nathans said of the collection. “There are interrogation records, personal letters, drafts of unpublished essays, and much more.”

“When I first opened up that stuff, I could not believe what I had found.”

During the trial, the wives of the defendants created an unofficial transcript of the proceedings. It was circulated via samizdat, hand typed and retyped copies that were distributed beneath the radar of Soviet censorship, and then later smuggled and published abroad.

Until Nathans completed his book, the samizdat transcript was the only known account of the trial, in which Sinyavsky was convicted and sentenced to seven years hard labor in the gulag in Mordovia, Russia.

“I always wondered, how accurate is it?” Nathans said of the unofficial transcript.

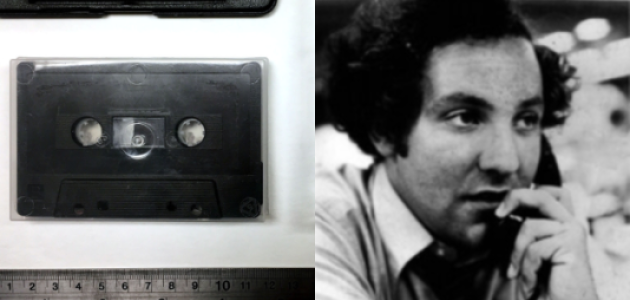

But what was sitting amongst other papers in Sinyavsky’s dossier at Hoover? An official KGB transcript of the trial, assembled with the help of an audio recording of proceedings.

Nathans compared the two.

“I was able to compare the two and to conclude beyond a shadow of a doubt, that the unofficial transcript, the one that became world famous, was about 99 percent accurate.”

“I could hardly believe what was in the Hoover archive,” he said.

Sinyavsky was eventually released and allowed to move with his wife and child to France, where he became a professor of Russian literature at the Sorbonne.

Interrogations, Pressure, Coercion

To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause chronicles other dissidents beyond Sinyavsky, including a man named Alexander Volpin. Volpin was a mathematician whom some viewed as crazy for the ways in which he opposed the Soviet regime in the early 1960s.

But his opposition was rooted in a simple demand, that the Soviet system abide by the laws it already had on its books, which would offer Soviet citizens some measure of civil rights.

For uttering that belief publicly, Volpin found himself facing tougher and tougher coercive measures of the state.

One of these measures was a lengthy interrogation.

Nathans includes the text of some of these interrogations, which could stretch for up to twelve hours in length, to highlight the banality of the Soviet system, and how Volpin drove KGB officers mad by not taking their bait.

Below, Volpin is questioned for holding a sign saying “Respect the Soviet Constitution” in Pushkin square on December 5, 1965:

Interrogator: Alexander Sergeyevich, why did you come to the square?

Volpin: In order to express that which I was trying to express.

Interrogator: But you were detained with a sign in your hands.

Volpin: I didn’t detain myself; why did others detain me?

Interrogator: No, but still, you were carrying a sign saying, “Respect the Soviet Constitution,” correct?

Volpin: Correct.

Interrogator: Why did you make such a sign?

Volpin: So that people would respect the Soviet Constitution.

Interrogator: What, do you think anybody doesn’t respect it?

Volpin: That was not written [on the sign].

“I include excerpts from interrogations throughout the book because you couldn’t make up better dialogues among the protagonists,” Nathans said.

Standing Up for a Hopeless Cause

Others who stood up to Soviet rule did so assuming their efforts would be futile—hence the book’s title, which is taken from a toast made by dissidents around kitchen tables in Moscow, Leningrad, Kyiv, and other Soviet cities. But Nathans said it was a combination of boldness and despair, wrapped together with the pervasive Russian sense of fatalism, that drove the dissidents to speak out.

“Many of them were driven, I'm convinced, even more by a sense that they just could not live with themselves if they did not do something, if they remained silent,” Nathans said. “These were in general very high-minded people, very idealistic people in an ocean of cynicism who just could not stand a version of themselves that was silent in the face of injustice or hypocrisy.”

The feeling of despair and futility came from a widely held belief amongst the public in the 1960s and 70s that the Soviet Union would go on forever.

One man who didn’t buy into that belief was Andrei Amalrik.

“He published an underground essay in 1969 called ‘Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984?’,” Nathans said. “So, he was off by seven years.”

A collection of Amalrik’s lectures in the US after he was exiled from the Soviet Union is housed at Hoover’s Library & Archives.

Nathans said of all the dissidents profiled in the book, Amalrik is the one he wished he could’ve met. But in 1986 he died tragically in an automobile accident in Spain.

“(Amalrik) was able to glimpse the fragility of the (Soviet) system in a way that almost nobody else could,” Nathans said.