Hoover Institution (Stanford, CA) — Across his careers of military service, scholarship, and teaching, Senior Fellow H.R. McMaster says, working with young people has been tremendously rewarding.

By sharing his experiences and incorporating the insights of his students, McMaster wants to ensure that the next generation of students at Stanford know that they have the knowledge, tools, and ability to overcome challenges and build a better future.

“It's really important for Americans to understand that we can achieve favorable outcomes through an effective foreign policy and national security strategy,” the former US national security advisor said. “I think a lot of Americans have lost confidence in our ability to do that, and it's led to a toxic or negative combination of resignation and defeatism.”

Throughout his courses and other exercises offered to Stanford students, McMaster encourages students to identify solutions for government and the commercial sector that improve security and prosperity.

In several of the classes he teaches for Stanford, McMaster says, he tries to give students new frameworks for understanding and solving problems as well as identifying and capitalizing on opportunities, frameworks he employed as a military commander and as national security advisor. He explains that there are three main components to that framework.

First is to develop a deep understanding of one or more of the contemporary security challenges facing the United States and avoid common pitfalls in policy and strategy development.

“Secondly, I ask students to identify the ‘so what’: why they and their fellow citizens should care about challenges to security and prosperity,” McMaster explains. “This is really important today, because many Americans are deeply skeptical about US international engagement and are advocating for retrenchment or disengagement.”

Finally, he wants the students to be able to develop and articulate well-defined goals and identify and challenge assumptions that underpin their understanding of problems and potential solutions.

Beyond the classroom, McMaster’s research assistants have identified and assessed policy tools relevant to trade, technological transfer, and international law that deal with what he calls “economic statecraft.”

Observing patterns of intellectual property theft, coercive trade practices, and research programs that initially appeared benign but later proved to be mechanisms for states like China to acquire sensitive defense-related work, McMaster asked whether there were a strategy he and the students could help develop to mitigate risks associated with academic and economic ties between China and the United States.

In the resulting paper, “we introduced a concept called small yard, high fence in terms of applying a combination of export controls and inbound and outbound investment screening, as well as other tools of economic statecraft,” McMaster said.

The recommendations in this paper later informed a 2023 memo on the topic drafted by the US Department of Commerce.

In another project McMaster leads, Geotrends, students from across Stanford participate in what Chelsea Berkey, McMaster’s senior research program manager, describes as a “mini–National Security Council.”

“It is kind of an ongoing seminar where we're learning from one another about the most significant challenges and opportunities we face in the world today,” McMaster said.

In Geotrends, students practice a distinct analytical style of writing used across the national security community. They also study and replicate decision frameworks and action plans that National Security Council members have drafted to advise the president on courses of action concerning urgent geopolitical developments.

“[We get] computer science majors, a fair amount of students from economics, but what we really do here is take an interdisciplinary approach to understanding the world,” said McMaster.

One former Geotrends participant was Arjun Tambe. At Stanford, Tambe majored in computer science, with a focus on using artificial intelligence to track the development of what he calls “symbolic systems.”

With McMaster, he identified and analyzed disinformation the Chinese Communist Party disseminated about China’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I worked on the ways that the [Chinese Communist Party] uses its state media, especially social media, to influence foreign coverage of the Chinese government,” Tambe said.

The research eventually led Tambe and another student to publish a paper about their findings in Harvard Kennedy School’s Misinformation Review.

But the partnership didn’t stop there. Tambe went on to participate in McMaster’s “economic statecraft” projects and research, with a focus on supply-chain disruptions that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Seeing the drastic changes underway in the world helped cultivate my thinking on what the world’s most important problems are,” Tambe said.

That experience shaped his next step: founding Kipo.ai, a company that uses artificial intelligence to help firms find the components they need by scouring all known suppliers of an item across the globe. It also can be used by governments seeking a complete map of what they need to procure and risks that may threaten their country’s supply chains.

Tambe credits McMaster with “shaping my thinking on how one can best influence the world.” They’ve kept in touch in the years since.

“[McMaster] has continued to be an incredible mentor,” Tambe said. “In concrete terms, he has guided my strategic business decisions and connected me to scholars and practitioners working on supply-chain resilience. Beyond that, he has helped me become an effective leader.”

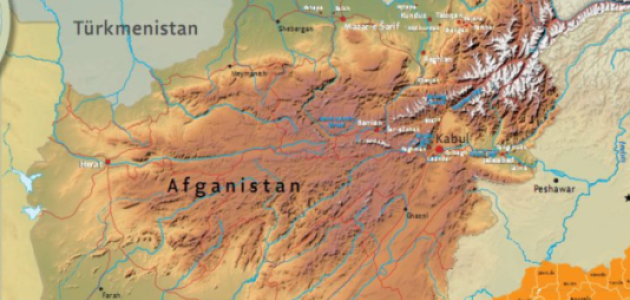

Teaching and mentoring have also meant supporting students as they confront the weight of real-world crises. McMaster saw that firsthand during the collapse of Afghanistan in August 2021, when students volunteered through the Hoover Afghanistan Relief Team to help Afghans who had supported US and allied forces.

The chaos, uncertainty, and stress of those weeks made an impression on some of McMaster’s students who assisted him. In one case, a person his students were working to get out of Kabul heard that his brother was killed by a group of Taliban fighters before they could get him out of the airport.

“The message was, don't worry about my brother anymore. He was dragged out of the house and shot in the head this morning.”

Dealing with the weight of a message like this was not something the students were accustomed to. “One of the things we did with our team is I talked with them like I would talk to soldiers who encounter combat trauma,” McMaster said.

Amid grief, students focused on the fact that their work made a tangible difference.

“What I think helped us cope with it was that we weren't standing by and just watching this, right? We were involved in making a real difference.”

The students’ efforts led to innovation as well. McMaster recalled a student, Lisa Einstein, who developed a database that could collect and store all the relevant information a person, in this case an Afghan, would need to apply for a Priority 1 or Priority 2 refugee visa.

“The State Department said, ‘This is better than anything we have,’” McMaster recalled.

The database informed the State Department’s approach to processing online Special Immigrant Visa and refugee claims in the first chaotic weeks of the withdrawal.

The work can be demanding — whether drafting sanctions recommendations or coordinating paperwork for crisis evacuations— but McMaster believes these experiences reinforce a central lesson: Resignation and defeatism are incompatible with securing a better future.

By involving students directly in addressing America’s security challenges, McMaster says, he wants them to recognize their capacity to lead and contribute to meaningful outcomes.

“A lot of this is along a theme of helping our younger generation understand that they do have agency to build a better future,” McMaster said.

Learn more about the Strategic Competence Initiative at Hoover here.