On October 4, 2016, before a capacity audience at the Hoover Institution offices in Washington, DC, leading researchers and university faculty presented their findings on whether alleged business practices that exploit the US patent system impede innovation. Maureen Ohlhausen and Scott Kieff, sitting commissioners of the Federal Trade Commission and International Trade Commission, respectively, also participated in the event.

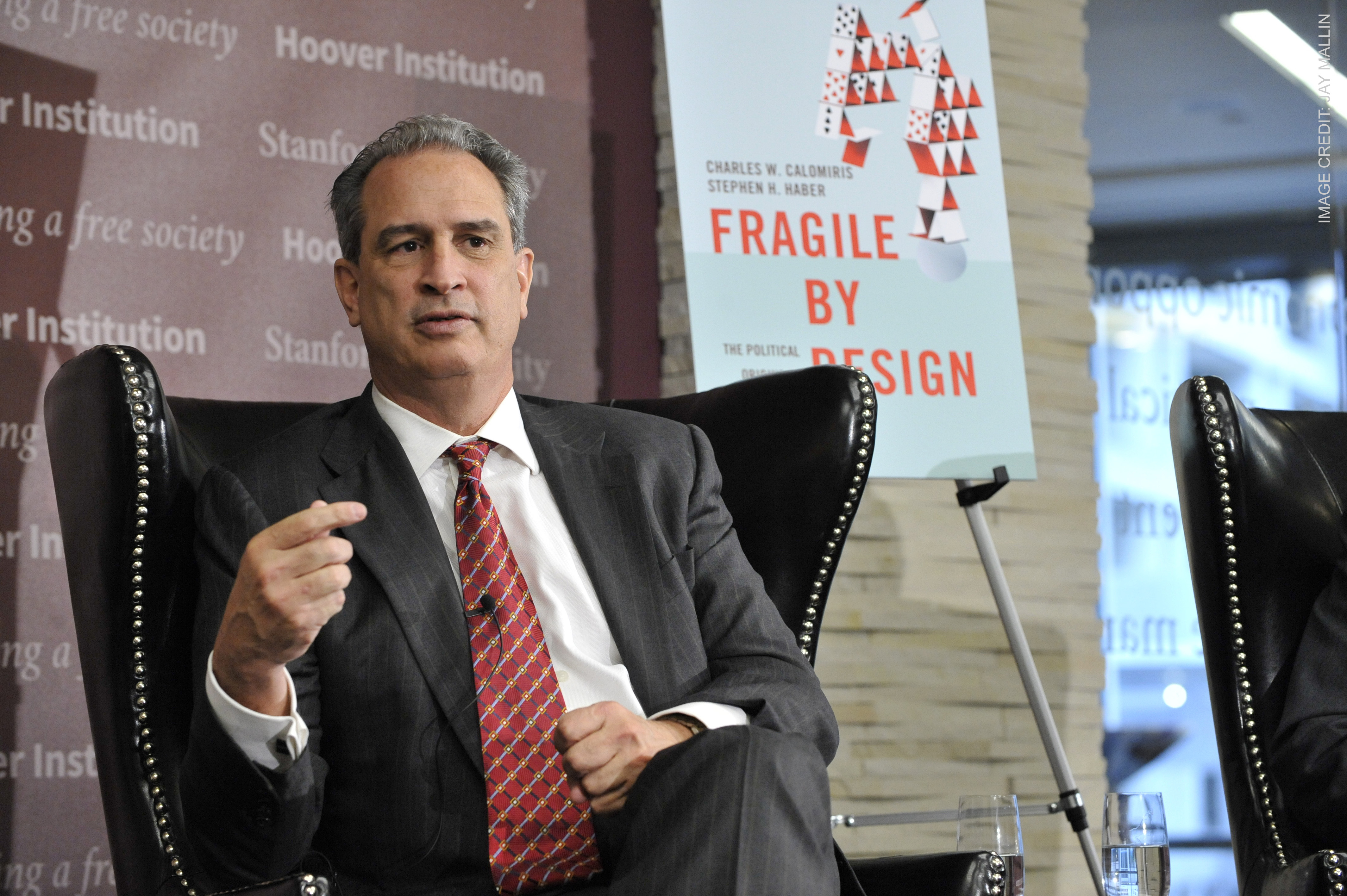

The half-day symposium, “Patent Holdup Theory: Implications for the Courts, Government, and the Legislature,” was organized by Hoover Institution senior fellow Stephen Haber and David Kappos, former director of the US Patent and Trademark Office, and sponsored by the Hoover Institution Working Group on Intellectual Property, Innovation, and Prosperity (Hoover IP²). The symposium’s goal was to provide jurists and law clerks, congressional and federal agencies staff, and others working on intellectual property issues with facts and evidence regarding patent holdup and royalty stacking.

Patent holdup occurs when the holder of a patent that is essential to the production of a product requires an exorbitant licensing fee or changes the terms of the initial licensing agreement solely for the benefit of the patent holder. Royalty stacking occurs when the production of a good requires a large number of patent licenses to be acquired and royalties paid, hence driving up the costs of producing the end product.

In opening remarks, Haber, who is the director of Hoover IP², said the symposium would address whether the US patent system allows the owners of intellectual property to engage in patent holdup and royalty stacking, thereby frustrating innovation. He said that the symposium’s goal is to look into the existence of patent holdup and royalty stacking using evidence and reason. He went on to say that when widespread patent holdup occurs in an industry, we should see prices is rising and innovation in the industry stagnating.

Panelists explained that the classical definition of holdup requires guile on the part of the patent holder, who, using opportunistic surprise, deceives those with to whom they grant licenses. It was noted that negotiating for a high licensing fee is not holdup and, further, that exercising market power and engaging in strategic bargaining alone are not indicators of holdup. It was concluded that holdup cannot be a long-run phenomenon, as producers will adapt and innovate.

Panelists agreed that monopolistic behavior and patent holdup require government intervention. They added, however, that government response has been muddled and, moreover, that various government agencies, depending on the degree to which they rely on contract law or anti-trust law, have not been clear on when they might intervene.

Data were presented from selected high-tech industries to demonstrate that royalty stacking and patent holdup are not supported by the data. In contrast to the theory, patent-intensive industries, where stacking and holdup are alleged to occur, are characterized by falling real prices and robust innovation.

The concluding advice to legislators, regulators, and jurists was that holdup and stacking are theoretically possible but infrequently (if ever) observed.

The symposium was one of the many offerings by Hoover IP², which examines broad issues of intellectual property rights through a series of conferences and symposiums and by supporting academic research.