- Middle East

- International Affairs

- Determining America's Role in the World

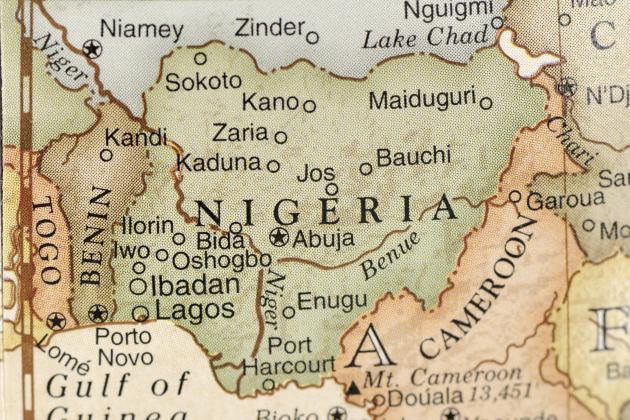

On October 31, 2025, President Donald Trump announced that he would be designating Nigeria as a “Country of Particular Concern” (CPC) over alleged persecution of Christians in Nigeria by “radical Islamists.” The next day, he upped the ante, threatening military action in Nigeria if the government failed to stop the killings of Christians. While the threat of military action surprised military officials (and may well just be an example of Trumpian bluster), this episode was not entirely unexpected, as concerns over alleged Christian persecution have long been a focus of some international religious freedom advocates and conservative lawmakers in the US, especially during Trump’s first term.

President Trump’s framing of Nigeria’s problems has domestic political appeal because it is straightforward and resonates with what a casual American consumer of the news might know about Nigeria: That it is a big African country, home to many Christians and Muslims alike, and that there is a jihadist group, Boko Haram, that gained notoriety for kidnapping a group of Christian school girls some years ago.

Those familiar with Nigeria know that there is much more to the story, but in light of President Trump’s announcements, the questions many Americans might understandably ask are more straight-forward: Are Nigeria’s jihadists not intent on killing Christians? And if so, do they pose an “existential crisis” to Nigeria’s 100-million-plus members of the faith, as Trump has claimed?

Jihadist groups, both from within Nigerian and from neighboring Sahelian countries, are indeed attempting to persecute and kill Nigerian Christians. But this does not capture the full picture of Nigeria’s insecurity. Firstly, these groups are only active in some parts of the country, while in many other parts of Nigeria, local conflicts are driven by factors other than religion. Secondly, the jihadi groups themselves employ simplistic and reductive narratives of Nigerian religious identities to justify their violence and appeal to new recruits. In their efforts to reframe all of Nigeria’s social divisions as fundamentally religious ones and spark a broader Muslim-Christian conflagration, these jihadists conveniently paper over significant complexities in the interplay between religion and ethnicity in Nigeria, as I will attempt to explain in this short contribution.

The implications are significant, though perhaps not in the ways one might think. Conflict has grown rampant in many parts of Nigeria over the past two decades, killing many Christians as well as Muslims. Yet jihadists have not always capitalized on that insecurity to expand and cement their influence in the ways that they have hoped to, in part because their fixation on religious identity and ideology leaves them ill-equipped to address the grievances and social divisions that actually drive local conflicts.

A religious conflict, or uncontrolled insecurity?

I have previously written and testified before the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom that Nigeria’s myriad conflicts cannot be reduced to a simple narrative of religious persecution. Yet when confronted by claims of Christian persecution, Nigerian officials have often been too quick to downplay the severity of insecurity and paint a rosy picture of ethnoreligious harmony. Nigeria is big, diverse, and complex, and one cannot ignore the many social cleavages that contribute to conflict in parts of the country.

A country of roughly equal numbers of devout Muslims and Christians,[i] religion has been a fiercely contested political issue for years. The military conquests of the Sokoto caliphate in the 19th century and subsequent period of British indirect colonial rule left a legacy of suspicion among Christian Nigerians in the Middle Belt states and the south against the country’s Muslim-majority Hausa and Fulani populations in the north, with the former generally fearing political domination by the latter. In 1967, shortly after the country’s independence, Igbo military officers and civil servants from the southeast declared a separate state known as Biafra amid escalating anti-Igbo pogroms in the north that had been spurred by a bloody coup and “counter-coup” that assumed ethnic overtones; the subsequent civil war lasted three years and killed over a million people, mostly civilians in the defeated Biafran territory, a dark legacy that engenders neo-separatist sympathies in the region some half a century later. For most of the period from 1970 to 1999, successive military regimes attempted to juggle competing regional interests that diverged sharply on questions of state policy toward religion.[ii]

Following the return of civil rule in 1999, newly elected governors in the Muslim-majority northern states moved to implement sharia law as coequal with common law (while officially granting exemptions for non-Muslims), sparking widespread protests and contributing to several bouts of ethnoreligious violence that killed several thousand in the 2000s. These urban riots or “crises” as they were known have actually been less frequent since the early 2010s, but the overall security picture has deteriorated at the same time, particularly in rural communities and particularly in the north. This insecurity includes the Boko Haram conflict, ethnic violence, and an upsurge in banditry. The violence has reignited popular fears in parts of the country of northern domination and “Islamization” at the hands of ethnic Fulani in particular.

Yet the country’s violence cannot be reduced to a single religious divide or ethnic group. Nigeria is facing multiple, distinct yet sometimes overlapping conflicts in nearly every sub-national division of the country. These conflicts involve a wide range of non-state armed groups—in 2022, the Armed Conflict Location & Event Database (ACLED) estimated more than 80 significant conflict actors, though one could argue it is much higher[iii]—that are frequently motivated by different community-based grievances as well as political and economic objectives. Whether a bandit leader in the Muslim-majority northwest, a pirate who practices traditional religion and steals oil from pipelines in the Niger Delta, or the commander of a self-styled Biafran separatist group in the southeast, these militants could be considered “violent entrepreneurs” of sorts,[iv] individuals who espouse the popular grievances of their constituencies while using violence to secure political influence (de facto, and sometimes de jure) and/or personal wealth. Added to this mix is a very real threat posed by jihadist militants, whom I detail in the following section and argue are indeed waging an ideologically rooted campaign to, at minimum, establish an “Islamic state” in one corner of the country (although these militants are also factionalized).

Individually, none of Nigeria’s militants are strong enough to topple the government. But collectively, these militants have carved out various fiefdoms such that segments of the country are beyond the effective control of the Nigerian state. This is more akin to a gradual, multifaceted state failure across several decades than a concerted attempt at conquest or regime change by one group. Yet some international religious liberty advocates confusingly lump these various conflicts together with other issues such as mob lynchings and blasphemy laws in the northern states to paint a picture of Islamists (somewhat vaguely defined) subjugating the country’s Christian communities, overlooking the fact that much of the country’s violence occurs within and between Muslim communities.

While it is beyond the scope of this article to analyze and litigate every communal conflict in Nigeria, this context is relevant for the purposes of this article insofar as it can be summarized as follows: Nigeria is facing many different conflicts, and despite the presence of broader religious tensions in the country, many of these conflicts are not directly about religion per se and more about ethnicity, land, resources, and political ambition. At the same time, the country is facing genuine religious militancy in the form of jihadist groups. The jihadist groups have, for their part, attempted to turn Nigeria’s myriad local conflicts into one overarching religious confrontation. They have largely failed to do so, however, as examined below.

The Boko Haram conflict: Takfir of Muslims, unrestrained violence against Christians

Jihadist groups in Nigeria are certainly, in their own understanding, waging a holy war. The scholarship on the Boko Haram conflict has amply documented how the movement emerged as a reaction to the widespread religious tensions of the first decade of the Fourth Republic (1999 to present), specifically as a radical faction of the broader Salafist movement that grew increasingly critical of the northern Nigerian political and religious establishment for failing to implement full sharia law without any exemptions.

Some two decades later, the Nigerian jihadist landscape is complex and highly fragmented. For the purposes of this contribution, it suffices to emphasize three principal groups that all emerged from the original Boko Haram movement led by Mohammed Yusuf in the 2000s.[v] These are:

- Jama‘at Ahl al-Sunna li-Da‘wa wal-Jihad (JASDJ) was the main “Boko Haram” faction led by Abubakar Shekau following Mohammed Yusuf’s killing by Nigerian police in 2009. This group initiated the insurgency in northeastern Nigeria, engaging in the spectacular seizure of towns there and gaining international notoriety for kidnapping the mostly Christian Chibok schoolgirls in 2014. Shekau was killed in 2021 in an encounter with a rival faction (see below) and JASDJ is now segmented between different commanders’ fiefdoms.

- The Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) originally emerged as a faction of a JASDJ in 2015-2016 and received the Islamic State’s official recognition as the movement’s franchise in West Africa. It is now the strongest Nigerian jihadist faction, operating principally in the northeast and often fighting JASDJ for territory.

- Ansaru, an early splinter of JASDJ formed around 2011-12 that was more internationally oriented than Shekau. This group established ties with al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and was largely dormant by 2016 but has reactivated in different parts of central and northwestern Nigeria since 2020, albeit with mixed results and a degree of factionalism.

That Boko Haram emerged as a result of intra-Salafi debates and fissures is important to understanding subsequent trajectories of violence. Abubakar Shekau developed an even more radical and personalist approach than that of his predecessor, Yusuf. After Shekau took control of the movement and JASDJ began the insurgency in earnest by 2010-2011, it began killing many Muslims in northern Nigeria, including by bombing mosques. Shekau’s conceptualization of takfir, the controversial practice of declaring a fellow Muslim an apostate, was so expansive as to include virtually any Muslim who did not willingly join the JASDJ insurgency. Notably, both Ansaru and later ISWAP split from JASDJ in large part due to their rejection of Shekau’s ultra-takfiri attitudes (which, notably, even Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi viewed as theologically and strategically misguided, hence the Islamic State’s decision to recognize the splinter faction as the official “West Africa Province”).

The ultra-takfiri attitude of JASDJ in particular, both under Shekau and his current JASDJ successors, has led some analysts to question the role of ideology in the conflict, arguing that the movement is now driven more by parochial interests or even that it is merely banditry in religious garb.

Ideology stills plays a significant role, however. I have interviewed several dozen defectors from these groups over the years who have clearly described their journeys both into and out of the insurgency through a religious lens.[vi] In other words, religious self-perceptions matter a great deal to Nigeria’s jihadists.

We should therefore take Nigeria’s jihadists seriously—in their intent if not always in their capabilities—when they speak of fighting disbelievers. These words are, quite horrifically, matched by actions. Both JASDJ and ISWAP are trying to eradicate Christians in their respective corners of northeastern Nigeria. While ISWAP is generally more selective in its violence toward Muslim civilians than JAS, preferring to govern and tax them instead of raiding them, this lenience does not extend to Christians. In recent years, ISWAP has often attacked Christian villages in southern Borno and northern Adamawa states—the parts of the northeast with sizable Christian populations—around Christmas or New Year’s holidays.

Nigeria’s jihadists have more recently been seeking to expand both westward and southward to break out of a violent stalemate in the northeast that characterized the conflict in the second half of the 2010s. Each group sees diverse potential benefits in expansion. Broadly speaking, these include the possibility of further bogging down Nigerian security forces (potentially leading to some respite from military offensives in the northeast), tapping into new sources of funding, establishing logistics lines to link dispersed cells, and gaining new recruits—the latter of which is particularly important groundwork for the sort of more ambitious, sustainable expansion across Nigeria that these jihadists seem to ultimately desire.

Yet as I detail in a forthcoming study, in the process of moving into different parts of Nigeria, these jihadists have faced obstacles insofar as religious and ethnic identities do not always align in ways that are convenient for them. A notable example is in northwestern Nigeria, which faces a staggeringly complex crisis in which intercommunal conflict, organized crime, and warlordism overlap in what Nigerians refer to broadly as banditry. Such a crisis should theoretically provide opportunities for jihadists to present themselves as security guarantors to vulnerable Muslim communities and win popular support, a strategy that jihadist groups have employed effectively in the Sahel. Except in Nigeria, the jihadists are not typically indigenous to the northwest, and the communities most involved in the crisis in the northwest are both Muslim—to generalize somewhat, ethnic Hausa farmers against Fulani pastoralists (some the latter having turned to banditry). This has created dilemmas for Nigeria’s jihadists: Which side of the intense ethnic conflict represents the “true” Muslims whom the jihadists should help protect?

Jihadist attempts to work with bandits in the northwest have largely failed due to the bandits’ refusal to surrender their autonomy and submit to strict religious codes. It should not be surprising that jihadist ideology has little appeal for bandits whose grievances are principally directed at their Muslim neighbors from another ethnic group. Nigeria’s jihadists have therefore sometimes found themselves aligning with Hausa communities to fight Fulani, contrary to the picture some Americans might have of an Islamist-Fulani convergence.

Similarly, in my forthcoming study on jihadist expansion, I show how in Kogi state in central Nigeria, ISWAP and Ansaru have recruited from a radical Salafist strain among the Ebira ethnic group as well as from the much larger Yorùbá population of the adjacent southwestern states. Both the Ebira and Yorùbá are religiously mixed with large proportions of the respective populations self-identifying as Christian or Muslim while also embracing aspects of traditional religion. Intermarriage between faiths is quite common, especially among Yorùbá, whom some northern Muslims have criticized for prioritizing “tribal” allegiance over religious solidarity in national political debates.[vii]

ISWAP and Ansaru have worked hard to maintain the secrecy of their cells in Kogi and the southwest, but we can deduce some general patterns of how they have attempted to aggravate religious tensions within such pluralistic communities. For one, they have attacked traditional Ebira masquerades on the grounds that they are un-Islamic. In ISWAP’s case, it framed its attacks as targeting Christians even though such attacks should be just as likely to kill Muslims, since Christian and Muslims alike engage in these traditional ceremonies. Moreover, Ansaru’s cells seem to have tried to align with some Fulani herders in the southwest who are aggrieved with Yorùbá communities over the establishment of a local security force that they claim routinely profiles and harasses herders. Yet the jihadist approach of backing one side in a conflict between herders and farmers is not so straight-forward in the southwest, because, among other factors, many Yorùbá farmers are Muslim.

In short, jihadist narratives that frame all of Nigeria’s problems as a religious war struggle to account for intercommunal conflicts between Muslim-majority ethnic groups or further the interests of communities that have a long tradition of interreligious coexistence. Needless to say, there is ample ideological pretext within Salafi-jihadi movement broadly and in the history of the Nigerian jihad specifically for the killing of Muslim civilians on various grounds, and jihadists have effectively navigated complex ethnic conflicts before, such as in the Sahel. We should therefore not expect that Nigeria’s jihadists will be too troubled by the contradictions in their approach or significantly moderate their violence. But we should, at minimum, not treat Nigeria’s conflicts as simply mirroring some broader fissure between Islamists and Christians. As with most things in Nigeria, there is more than one layer to the story.

Conclusion

Emphasizing nuance when discussing violence of the scale and nature that Nigeria has been experiencing is not always appealing, least of all in a society as polarized as Nigeria. In some regards, whether a group of herdsmen attacked a village in Benue state as a result of jihadist ideology or grievances over anti-open grazing laws does not change or somehow justify the fact that 200 people died in one such attack alone this past June.

The nuance is important for many reasons, however, not least among them because our diagnosis of the problem has tangible implications for which solutions are pursued. Farmer-herder conflict and jihadist expansion have been managed relatively effectively in other West African contexts, but they require tailored approaches that are rooted in a clear understanding of the problem. Reducing all of Nigeria’s myriad problems to anti-Christian violence[viii] does not ultimately help Nigerians.

Moreover, framing Nigeria’s crisis as a war between Muslims and Christians echoes aspects of jihadist talking points, which are more representative of the Nigeria that jihadists wish to see than the one that actually exists today. Pushing back against this framing is not simply something that should be done rhetorically for purposes of promoting some NGO-ized concept of “interfaith harmony.” As analysts and policymakers, recognizing this complexity can help forecast the evolution of these jihadist insurgencies, including by identifying parts of Nigeria where jihadists are likely to face greater skepticism or resistance from local communities.

It has been more than two decades since the first abortive uprising launched by a faction of Boko Haram. Mohammed Yusuf’s successors are no closer to achieving the Islamic state that he envisioned, but thousands of Nigerians have died with countless more injured or displaced in the intervening years, and popular confidence in the Nigerian state has been badly damaged. For each year that the conflict persists, jihadists will find more opportunities to probe into new regions and experiment with different forms of popular outreach, potentially making them more resilient as they learn from their past mistakes. The Nigerian government and its partners must take seriously the risks of jihadist expansion, while recognizing that Nigeria’s size and complexity defy simple solutions.

James Barnett is a DPhil candidate in political science at the University of Oxford and a non-resident fellow at Hudson Institute and the Centre on Armed Groups specializing in African conflict studies.

[i] Nigeria’s last official census was conducted in 2006. While official population projections based on the 2006 census show Muslims constituting a slight majority, these figures are hotly contested given their political significance.

[ii] These questions were also pronounced during a brief interregnum of civilian rule from 1979 to 1983 known as the Second Republic. Debates over the status of sharia law in northern Muslim states were particularly divisive during the constituent assembly that paved the way for the 1979 constitution, foreshadowing the divisive “Sharia politics” of the Fourth Republic (1999 to present). For more, see Vaughan, Olufemi. "Chapter seven. Expanded sharia: the northern Ummah and the fourth republic". Religion and the Making of Nigeria, New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2016, pp. 158-180. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478091172-009.

[iii] For example, the so-called bandits in northwestern Nigeria alone are organized into dozens of gangs. Estimates are highly imprecise given the loosely organized and fragmentary nature of Nigerian banditry. For more, see Peer Schouten and James Barnett, Divided They Rule? The Emerging Landscape of Banditry in Northwest Nigeria, Danish Institute for International Studies, August 2025, https://www.diis.dk/en/research/divided-they-rule-the-emerging-landscape-of-banditry-in-northwest-nigeria.

[iv] This concept as it has traditionally been understood in political science does not apply neatly to most Nigerian militants, as I am exploring in my doctoral research.

[v] Mohammed Yusuf never referred to his movement as Boko Haram, which is a name that was given to the group by its Muslim detractors in northern Nigeria. Early adherents of Yusuf’s were often referred to as Yusufiyya (literally, followers of Yusuf), while the organization that Abubakar Shekau led in the aftermath of Yusuf’s death referred to itself as JASDJ.

[vi] More often than not, these trajectories can be briefly paraphrased as: “I joined the movement because I believed what its members said about Islam, and I left the movement because I grew disenchanted with their violence against fellow Muslims, including women, children, and members of the other factions.”

[vii] Notably, no southwestern states have introduced sharia law, and recent discussion of establishing sharia courts for Muslims to voluntarily submit cases was met with widespread criticism in the region, including from some Muslims. See: https://www.theafricareport.com/375018/nigeria-sharia-panels-trigger-disquiet-in-south-west-region/.

[viii] In another variation of this framing that is common among religious liberty advocates in the West, one hears about how radical Nigerian Islamists are killing Christians and “moderate Muslims.” While this has the benefit of acknowledging the many Muslim victims of violence in Nigeria, it can also be misleading. If by “moderate” Muslim one means a non-Islamist or someone who is lax about following Islamic laws and norms, then Nigeria’s bandits are exemplars of this moderation insofar as they generally have limited religious education; do not apply anything resembling sharia law in the communities they control; engage in vices such as drugs and alcohol; and are disinterested in establishing an Islamic state. Yet these bandits have killed thousands of Muslims and Christians alike, reminding us that Islamism is not the only or even principal driver of violence in northern Nigeria.