Rather than gazing into a crystal ball and pretending to know how the Supreme Court’s abortion decision will impact California and the November election, let’s be honest: it’s too early to tell.

The calendar tells us as much: come next Tuesday, we’ll still be 18 weeks away from Election Day. That’s plenty of time for other matters to dominate a remarkably fluid news cycle in this election year, in which a diverse set of events—Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in late February, the Uvalde mass shooting in late May, inflation and gasoline prices for months now—have taken turns dominating the headlines, only to give away to a new national obsession.

One other reason for caution when it comes to forecasting California politics: the state’s history of “wild card” occurrences that shape both candidacies and campaign narratives.

Three such examples:

In 2010, news reports that then gubernatorial hopeful Meg Whitman had fired a housekeeper/nanny on the grounds that her employee was an undocumented immigrant. The allegation that Whitman refused to help her employee earn legal status fueled the narrative of a heartless billionaire (Whitman having made her fortune as CEO of eBay) and helped pave the way for Jerry Brown’s 13-point victory that November.

Another California wildcard, one that preceded an election year: the October 1993 murder of Polly Klaas—at age 12, kidnapped at knifepoint during a slumber party in Petaluma and later strangled to death by a career criminal named Richard Allen Harris, who soon became the public face of revolving-door justice in California. The event sparked a public demand for criminal-statute reform, and the following June, 72% of Californians approved Proposition 184 and a new “three strikes” law for repeat felons (a few months later, tough-on-crime Republican candidates would prevail in the statewide contests for governor, attorney general, treasurer, insurance commissioner, and secretary of state).

And yet another wildcard: the August 1965 Watt Riots—six days of civil unrest in South Central Los Angeles set off by a young African American motorist who was pulled over and arrested on suspicion of drunk driving by a White California Highway Patrolman. The political wrinkle: then governor Pat Brown had the unfortunate luck of being on vacation in Greece at the time of the civil unrest, therefore not on site and seemingly not in control of the situation. When Brown ran a year later for a third term, his performance during the crisis, coupled with the notion that another four years in office was perhaps overstaying his welcome in Sacramento, strengthened the case for first-time candidate Ronald Reagan, whose maiden campaign was a preview of right-of-center issues that would benefit conservative candidates for decades to come.

How then to project last week’s legal decision onto California’s political landscape?

Let’s start with what’s set in motion: a ballot initiative.

SCA 10, passed earlier this week by California’s state legislature and now awaiting voter approval via the November ballot, would add the following to the state constitution: “The state shall not deny or interfere with an individual’s reproductive freedom in their most intimate decisions, which includes their fundamental right to choose to have an abortion and their fundamental right to choose or refuse contraceptives.”

Why such a ballot measure? To animate the Democratic base—the youth vote in particular (CNN polling from earlier this year shows that only 10% of under-30 voters were extremely enthusiastic about voting in November).

Second, the media’s continued fascination with California as America’s progressive safe haven.

Every weekday, the New York Times emails a “California Today” missive to its subscribers. Monday’s edition included these words from the firebrand attorney Gloria Allred: “A lot of women and girls are going to have to become abortion refugees, leaving their home, looking for another state where they can get a legal and safe abortion. We are a haven state, a sanctuary state, in California.”

Watch the media lionize Golden State lawmakers in the weeks ahead as they advance an abortion-rights agenda in Sacramento (allowing certain nurse practitioners to perform first-trimester abortions without a doctor’s supervision; protecting doctors from legal and financial penalties if they travel to other states to perform abortions; no longer requiring coroners to investigate the cause of fetal deaths from suspected self-induced abortions).

Third, keep an eye (or an ear) on candidates’ abortion rhetoric.

In the race for the vacant state controller’s seat, Democratic hopeful Malia Cohen has run hard on identity politics (she’s the first Black woman elected to California’s Board of Equalization). Among her “equity” bullet points, and listed after housing, retirement security, and the economy: “Reproductive health care is under attack. Malia will fight to protect it.” Let’s see if those words now appear in October television spots.

A fourth consideration: voter registration. As of late May, 81.5% of eligible voters were registered to participate in California elections (nearly 21.9 million Californians in all, with nearly 5 million eligible Californians unregistered). Does the Supreme Court decision bump that number? Also, do pro-choice Republicans change their affiliation from GOP to “no party preference” (at last count, Republicans account for 23.9% of registered voters vs. 22.7% NPP and 46.8% Democratic)?

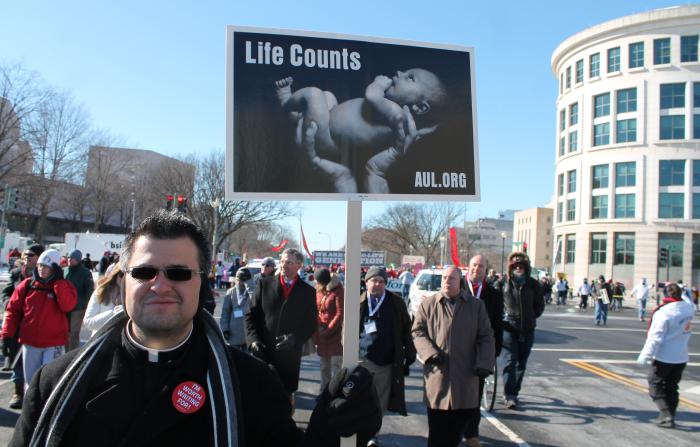

Finally, a fifth consideration: can the left harness the present outrage—multiple days of protests in downtown Los Angeles by pro-choice activists being one such example—and rechannel that energy from angry disobedience to election gains?

The last election cycle offers a cautionary tale: the May 2020 death of George Floyd prompted 140 protests across the US, with the National Guard being activated in nearly two dozen states. But amid the question of racial injustice: bad visuals (remember CNN’s “fiery but mostly peaceful protests”?) stepped on the message. Again, Los Angeles provides a good example of how to lose sympathy: last weekend’s arrest of a demonstrator accused of attacking a police officer with a “makeshift flamethrower.”

Overlooked in the sound of fury durig the last of the last presidential election was voters delivering something of a split verdict: President Trump was denied a second term; meanwhile, Republicans actually gained 14 seats, including four in California (a so-called Republican “red riptide” in 2020 appearing after 2018’s Democratic “blue wave”).

Looking inside 2020’s numbers: the total number of votes cast for Republican House candidates was 1.4 million less than Trump’s vote total, while Democratic House candidates were 3.9 million votes shy of the victorious Joe Biden.

Another way to phrase that: the Democrats’ desire to nationalize the election—i.e., turn it into a massive anti-Trump referendum in which down-ticket Republicans were dragged down by presidential suction—didn’t pan out. That was especially true in California, which Biden carried by nearly 30 points. Despite Trump’s obvious toxicity in the Golden State, winning GOP candidates survived by running on local pedigree and more local concerns (in the case of congresswoman Young Kim, among the first Korean American women to serve in Congress, a promise to deal with immigration, healthcare, and simplified business regulations).

How would this translate in 2022 terms? While Democratic hopefuls might do their best to “nationalize” the election as a referendum against a conservative Supreme Court (abortion, gun rights, school choice) and, by default, Trump (for nominating half of the bloc of six conservative justices), Republicans in California may choose to “localize” their contests by turning to more parochial matters such as the price of a gallon of gasoline or a shopping cart of groceries.

Not that this is a crystal-ball prophecy, but the November battle line may be as simple as “body” (women’s reproductive rights) vs. “pocketbook” (inflation and an uncertain economic outlook).

And which side will get the better of that argument?

The crystal ball says: check back with us in 18 weeks.