- State & Local

- California

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Campaigns & Elections

For a decade and a half now, California has lived a fantasy: Place all statewide candidates on one primary ballot, let voters choose their two favorites, and the result will be at least one hopeful who survived the primary by fashioning a centrist persona that resonated beyond partisan bases.

Or so was the vision when California voters, back in 2010, signed off on Proposition 14 and a new primary system that advanced the top two vote-getters to the general election, regardless of political affiliation. (The new system applied to elected statewide and legislative officials as well as members of Congress.)

What California candidates soon recognized: The system can be easily gamed.

Take California’s 2018 governor’s race. Faced with the prospect of a November runoff against fellow Democrat and former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, then lieutenant governor Gavin Newsom launched attack ads against Republican John Cox. Why? Because Newsom knew that such attacks would elevate the decidedly conservative Cox past Villaraigosa and into second place in the primary—i.e., easy pickings in the general election, considering that Newsom’s party enjoyed a 20-point advantage among registered voters.

The tactic repeated itself in 2024 and California’s most recent US Senate race. Rather than appeal beyond his Democratic so as to attract to Republic or unaffiliated voters, then congressman Adam Schiff ran ads targeting Republican Steve Garvey. But this plot had a twist: Then congresswoman Katie Porter (currently a gubernatorial candidate) ran ads touting the conservative bona fides of Republican Eric Early. Why would a diehard progressive like Porter, who drinks from the collectivist well of Elizabeth Warren, talk up a conservative foe in favor of limited government and free markets? Simple: Porter wanted to take votes away from Garvey and thus better her chances to finish first or second alongside Schiff.

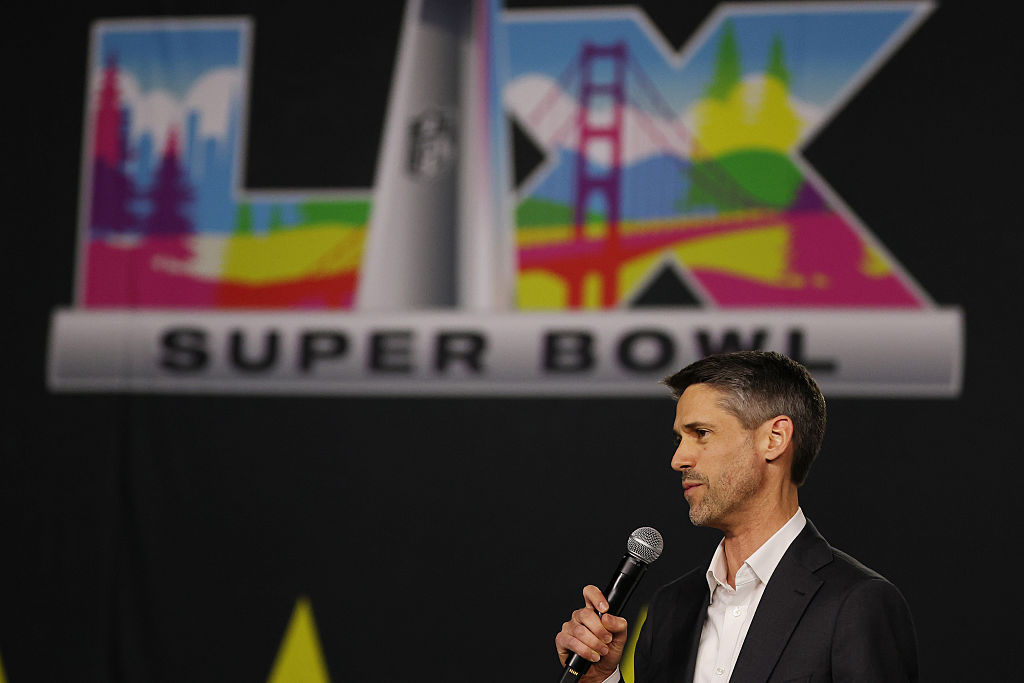

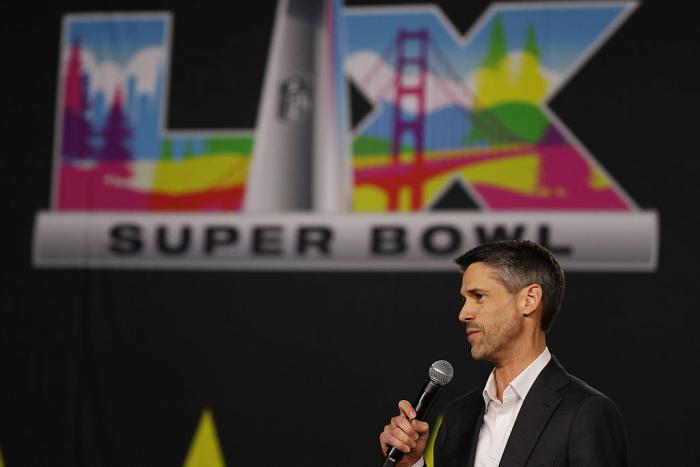

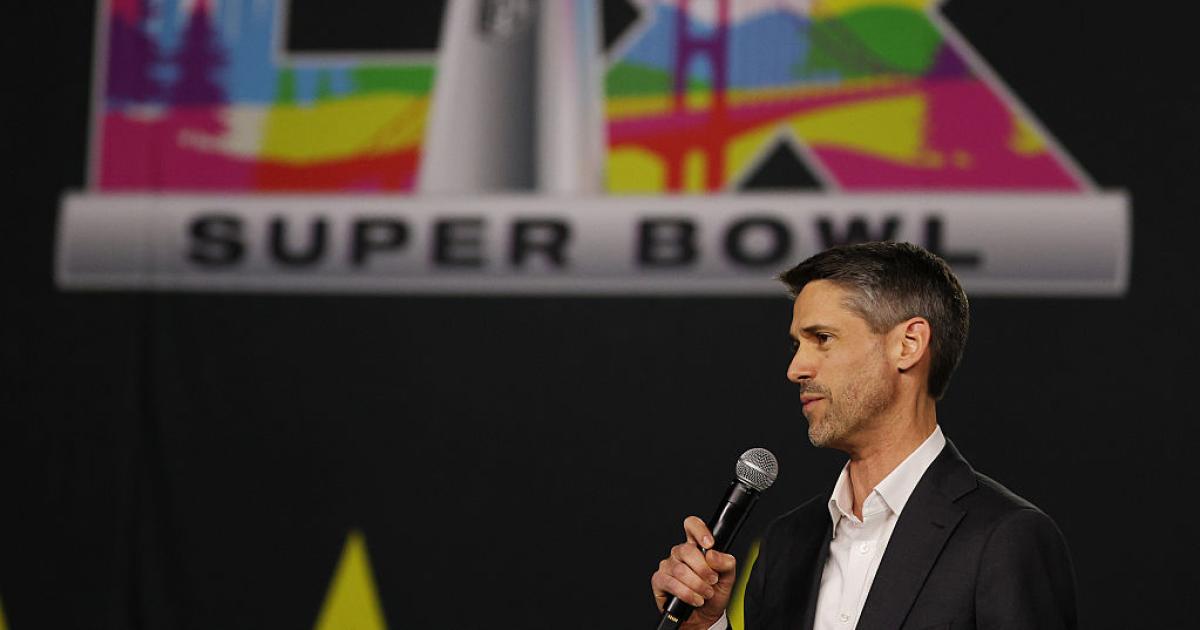

The question in 2026: Can one gubernatorial candidate use his centrist persona to survive the June primary? That would be San Jose Mayor Matt Mahan, the eighth Democrat to enter the contest but the only current incumbent willing to criticize Newsom’s job performance. (Villaraigosa likewise is running, but he hasn’t held office since 2013.)

By now, the Mahan-Newsom dynamic is well chronicled: The governor boasts, the mayor roasts.

Take the topic of homelessness. After Newsom announced a partnership last fall to help San Jose lower its unsheltered homeless population, Mahan took to social media to flame the governor: “We are literally taking over the maintenance of state land because they can’t do it. But hey, if the Governor needs to get credit to do the right thing . . . we’ll let him have it.”

Prior to that, in this August San Francisco Standard op-ed, Mahan lit into Newsom for, in effect, governing while distracted:

Gov. Newsom’s supporters say he is “breaking the internet” and “owning” Trump. But the governor, and every elected official and leader, also need to own up to the truth. And the truth is that California has the highest unemployment rate in the nation . . . and nearly half the nation’s unsheltered homeless people. We have the highest energy and housing costs in the continental United States, and, largely because of these high costs, the highest effective poverty rate in the nation.

Mahan, in his campaign announcement, didn’t take a direct swipe at Newson. That said, he made it clear that’s he’s not a fan of Sacramento’s status quo: “I’m running to bring focus back to government. To give cities the tools they need to succeed. To show that the best resistance to division is results,” Mahan said in a post announcing his candidacy. “And to prove that California can work again—for everyone.”

As for Mahan’s platform, the slogan is “Back to Basics,” summed up in five policy points: Build more housing; build more homeless shelters; require treatment for the homeless population’s drug, alcohol, and mental health woes; root out government fraud before resorting to higher taxes; bring back the SAT and the “science of reading.”

(A historical footnote: if elected, Mahan would be the first California mayor in modern times go straight from city hall to the governor’s office. Los Angeles mayors Tom Bradley and Sam Yorty—each running twice for governor in a two-decade stretch from 1966 to 1986—Newsom, Pete Wilson, and Jerry Brown (in his second incarnation as governor) all were former mayors at the time of their election.)

The next question is: How far can Mahan get with his message, designed to reach beyond the Democratic base? The answer involves at least three variables.

Money. Unlike the billionaire Tom Steyer, a hedge-fund founder who’s poured millions of his personal fortune into an inescapable ad blitz for weeks now, Mahan doesn’t possess a vast personal fortune. (At least count, Steyer’s $27 million in expenses since entering the race three months ago is nearly seven times that of the next biggest spender, Republican Steve Hilton.)

What the mayor does have: wealthy and perhaps generous friends in high places (half of the world’s 10 richest billionaires live in proximity of San Jose). They include Mahan’s Harvard dorm mate Mark Zuckerberg (presumably impressed by Mahan’s opposition to a proposed ballot measure that would impose a one-time 5% tax on California billionaires).

A word of caution about wealthy donors: Under state law, an individual can give $39,200 in both the primary and the general elections to a gubernatorial candidate. But there’s another, perfectly legal way to show support: Give millions to an independent expenditure (IE) committee to boost a candidacy (which happened in California’s 2018 governor’s race when charter school advocates like Michael Bloomberg and the late Eli Broad bundled millions to help Villaraigosa). Don’t be surprised if a pro-Mahan IE emerges as the contest moves closer to the June 2 primary.

Payback. Newsom, when asked about Mahan’s candidacy, went out of his way to seem nonchalant: “I don’t know enough about him, I wish him good luck.”

Having myself worked in the communications shop of a California governor who cared little for intraparty critics (the aforementioned Wilson), I can assure you: Newsom—and his hyperbolic social media operation that rarely lets a dig go unignored—are very aware of Mahan’s candidacy.

The question: Is Newsom willing to engage in the race—not by endorsing one of Mahan rivals but by letting Sacramento’s special interests understand that if you want to play ball with the governor in his last year in office, do not donate to the Mahan campaign?

Downsizing. Mahan enters a crowded field that includes eight fellow Democrats: Villaraigosa, Porter, and Steyer; former State Attorney General and US Secretary of Health and Human Services Xavier Becerra; former Assembly Majority Leader Ian Calderon; US Rep. Eric Swalwell; State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond; and former State Controller Betty Yee.

And on the Republican side: Hilton, a former Fox News host; Riverside County Sheriff Chad Bianco; and tech entrepreneur Jon Slavet.

While polling in the race is scant, it’s this mid-January sampling that may prompt Democrats to consolidate their side of the field by the March 6 filing deadline.

What that poll showed:

| Bianco | 17% |

| Hilton | 14% |

| Porter | 11% |

| Swalwell | 11% |

| Steyer | 8% |

| Becerra | 5% |

| Villaraigosa | 3% |

| Thurmond | 2% |

| Calderon | 1% |

| Slavet | 1% |

If this pattern holds through the remainder of this month, look for two things: pressure on the single-digit Democrats to drop out of contests; and perhaps the same mischief as in previous primaries, i.e., Democrats spending money to elevate Slavet’s campaign and thus try to push Hilton or Bianco into third place.

Meanwhile, open-primary math makes for odd politics—for example, Hilton, using the recent candidates’ debate in San Francisco to tear into not only an absent Bianco, but Mahan as well. Why would Hilton bother with Mahan? Simple: to try to limit Mahan’s crossover appeal with independents and Republicans.

Such are Mahan’s challenges between now June 2: to raise money, to elevate his name recognition beyond the San Francisco Bay Area media market, and to light a fire in a contest most notable for who’s not running (former Vice President Kamala Harris and US Sen. Alex Padilla).

And should Mahan’s nonconformist campaign come up short, Californians once again can ask: Why doesn’t an open primary designed to benefit centrists and coalition builders keep failing to live up to its promise?