- Understanding the Effects of Technology on Economics and Governance

Energy realities and climate policy provide the factual foundations necessary to understand the interaction of Energy Policy, National Security, Economic Prosperity, and Environmental Stewardship.

The experts provide vital information on Energy supply, growing energy demand for AI, the limited impacts of climate policies on actual climate outcomes, and the need to accommodate energy realities as the basis for policy decisions.

Emphasis is placed on several realities; 1) The vast size of the US and global energy sector, 2) While renewables have grown rapidly, they added to energy sources that on balance have not much replaced fossil fuels, which have continued to grow and still account for 80% of energy supply, 3) The need for a full cycle evaluation of climate policies to assess their net impact.

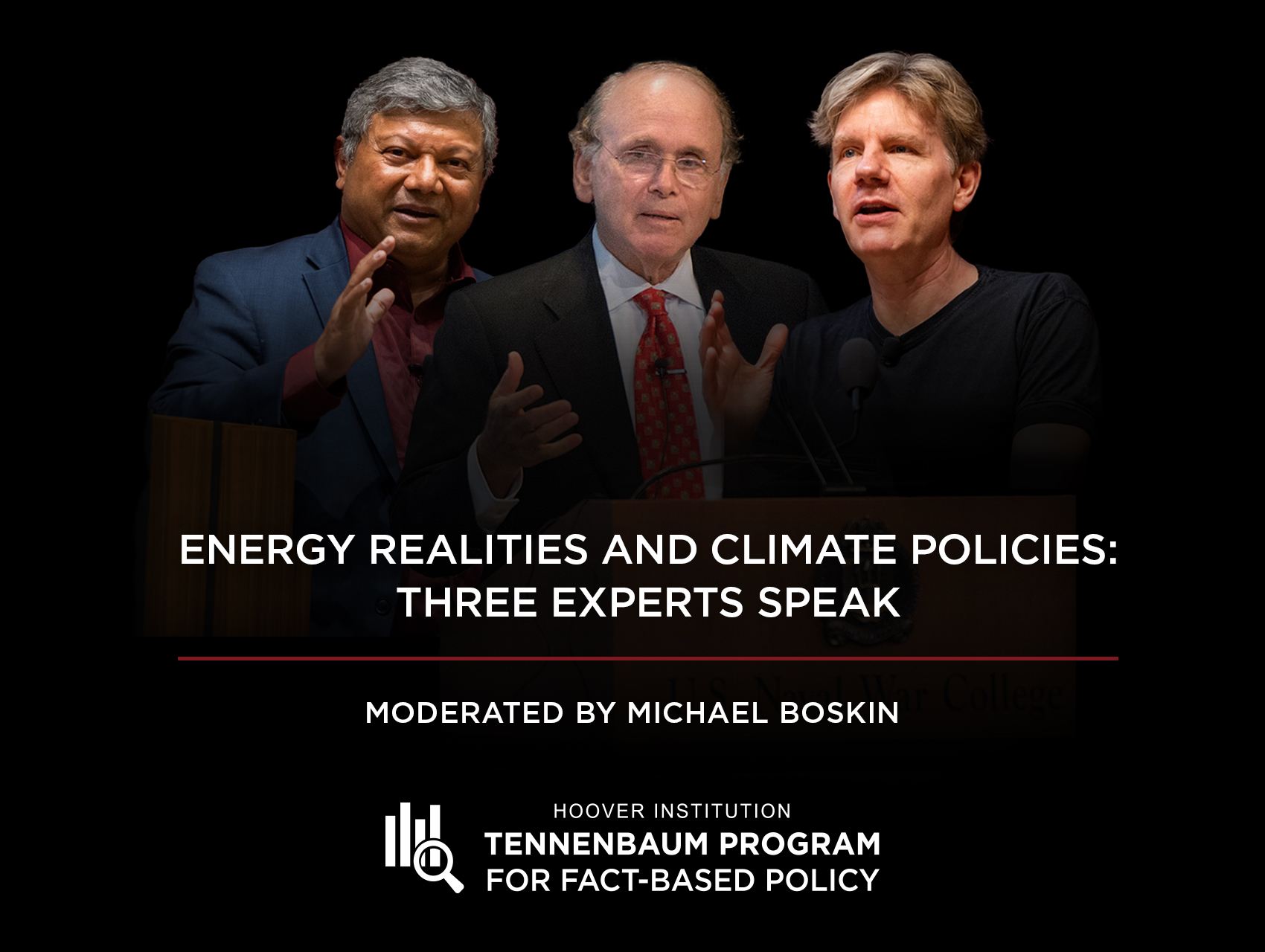

- Hello everybody. Welcome to Factual Foundations of Policy, a production of the Hoover Institutions Tennenbaum program for fact-based policy where we impartially investigate the most controversial and important public policy issues facing the United States and indeed often the world. I'm Michael Boskin, the Rose and Milton Freeman, Senior Fellow on Public Policy here at Hoover. Italia Am Freeman, professor of Economics at Stanford, and former chairman of the President's Council of Economic Advisors. Today the topic of our show is how America can generate policies that provide the conditions for the production of durable, efficient, and as necessary clean energy resources while also preserving our natural environment. But to generate constructive policies, we need to cut through the noise on what can be a contentious debate and rely on a solid foundation of facts. Joining me in conversation today are three highly regarded, distinguished experts who are, who have spent much of their careers working on these subjects, and indeed are regarded as among the most important speakers and scholars on this globally. Arun Majumdar,, one of the nation's leading voices on creating a sustainable energy future. He served as under Secretary of the Energy of Energy, and among many posts he has at Stanford, he is currently the founding dean of the Do School of Sustainability, and he was also the J Pre-court Provostial chair, professor, and a senior fellow here at Hoover. Bjorn Lomborg is a visiting fellow here at Hoover, is also president of the Copenhagen Consensus Center. His work highlights and advocates for efficient evidence-based strategies to address the world's most pressing challenges, including climate change, but also global poverty and access to efficient energy resources. Daniel Yergin is the leading authority on energy, perhaps the leading authority on energy geopolitics and the global economy, the winner of the Pulitzer Prize. He has been referred to by the New York Times as America's most influential energy pundit. Indeed, when I wanna start thinking about energy, I start with Dan and often that's sufficient. Also, he is currently vice chairman of SP Global. So with all three guests who contributed to an ongoing series of s readable and accessible essays that are available at hoover.org/tannenbaum, please access those. If you'd like to hear more about, read more about these subjects, let's start. However, after, welcome to our very special podcast. Let's start by asking a series of questions and ask each of them to comment as necessary, as desirable. And feel free, we'll go with the flow. Feel free to work, to work in anything you wanna say. We don't have to always go in ex in a precise order. But Dan, can you give us a, a brief summary of where US energy, production, consumption, trade balance, and the like stands and compared to where we were a couple of decades ago? And let me start by saying obviously immense, a number of things have changed around the world. In energy Shale, for example, is gigantic, but also Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the new geopolitics with China being a potential major adversary Europe and its energy issues, a tremendous increase in demand for electricity from ai. All those things are going on, but you're the expert, Dan, so over to you.

- Well, I, I think first of all, it's great to be here on behalf of all, all three of us. Very pleased to be on with you Michael, and to be part of this series and, and the impact that the series has. You know, in a way you summarized it, I'll just say two things. One, if you compare it to where we were less than two decades ago, it's 180 degrees change in the US energy position. The only question decade and a half ago was how high would US oil imports go? Now the US because of the shale revolution, is the largest producer of oil in the world. Largest producer of natural gas, the largest exporter of LNG. And that has had big geopolitical consequences because I mean, you know, Putin's effort to shadow the consensus support in Ukraine might well have worked, were it not for the fact that US LNG could replace a substantial amount of that Russian gas. I will say just one other thing to add to it. Obviously you've, we're gonna get into what AI means for energy, but I think in many quarters thinking is not caught up by any means with the change either in the energy position of the US and what it means and its significance, including what it means for consumers. But in terms of prices, and it certainly as we will get into, has not caught, caught up to what we've learned over the last few years about the energy transition. But I know we'll pick that up in a few minutes.

- Yeah, I should add, by the way, that Dan and co-authors have a really important piece in foreign affairs recently, and I refer everybody to that on exactly the topic he just mentioned. Arun, let's turn to you next. You've written in our, in our series and been an advocate for policies that harmonize economic economic interests, national security interests and environmental interests. So maybe you can give us a bit of an idea of the evolution of low or zero emission energy sources, the use over the same time span and where they stand today, how far they come, how far they need to go before they actually scale to something that's much more significant than they are now.

- First all, Michael, thanks for having all of us and leading the ALM series of articles. Let me start by just picking up where Dan left off. I think the, if you look at the history of shale revolution and really with technology innovation going back to the 1980s and then it took about, you know, 25 years or so to make it with a cost coming down over time that when I was in the DOE in 2010, it became cost competitive. And that has actually pushed out, you know, coal et cetera, that is more emission, the higher emissions. So over the time, the technology evolution that you've seen also in solar and wind has actually brought the cost down substantially. I would also say that the grid, the Tesla led in grid architecture was really not designed for solar and wind, but the evolution of gas that has come down is now balancing that. And so we can now add, you know, solar and wind to the grid as well as the battery costs are coming down dramatically. And that's, we are seeing on a daily level. It's, you know, the lithium ion batteries cost has come down. And so from the electricity side, this is a really good, we have more options. Now, the only thing I would say is that the nuclear cost has actually gone up. It has a negative learning rate. And from what we are seeing right now, there's a nuclear, I would say renaissance nuclear going on in terms of both the fuel cycle as well as the technology, the small modular reactor. So we expect, we are hoping that the cost would, would come down, but it, this has been the last, I would say 20, 25 years has seen all these options, you know, come around for the grid, which were frankly not there as cost effectively before.

- Okay. So the grid remains a challenge.

- The grid remains a challenge. As you were pointing out earlier, the demand growth that we are now seeing because of AI data centers is, is dramatic. I don't think the electricity sector has seen this kind of demand growth. And there's a, you know, there's a huge amount and we can, I'm sure we'll get into it on terms of, you know, permitting reform to get transmission line and infrastructure to be built. That is one of the biggest bottlenecks going on in the United States right now.

- Well, one of the things we've seen is an about face close to 180 return on policy after lots of subsidies and mandates and regulations in the Biden earlier in the Obama administration, but certainly in the Biden administration. Lots of money being thrown at this by the federal government. We've seen in about face in the Trump administration's policies, negating, reversing, limiting, challenging some of these. And we, for a while I thought this was primarily gonna be just the federal level, but actually Governor Newsom in California has done an about face and is now encouraging fossil fuel production, trying to keep refine open, trying to reform permitting along the lines. You just said Arun, I guess some people think this is 'cause he's getting ready to run for president, he doesn't want an energy disaster in California to, to get in the way. But is this likely to continue? We've seen beyond, many nations have made these announcements and commitments and you know, targets for energy transition, net zero, all these kinds of things. And where do they stand today? Has it done much for emissions? I know there've been studies that suggest many of these policies actually haven't done much, but you're an expert on this. He's looked at it carefully. What's your, what's your analysis of where this stands today and maybe get us headed in the right, where should we go in the right direction?

- Well thanks Michael, it's great to be here. So look, fundamentally the problem here is that for the US and it's a fun sort of conversation, you've just had a lot of conversations about how you want to get more energy for the rest of the world, or I should say for the rest of the rich world. You're right, this is mostly a conversation about climate and a lot of nations, especially the European Union where I come from, we've been very focused on emissions. But the reality of course is there's not much happening, lots of promises, but very little happening. Look, remember the world keeps getting better on what we call the carbon intensity, essentially CO2 per dollar produced. It has come down certainly for the last half century or more, but it hasn't changed. It's gone down about oh 1.9% per year over the last three or four decades. And the Paris agreement, which everyone thought was gonna dramatically change how the world deals with, with the climate problem, has done nothing to change that if we were actually gonna reach our promises, we would have to see an 8% decrease every year, instead stuck around 1.9%. So we're just not doing this. We're not living up to the promises that we have made. And certainly most of the rest of the world is not really paying attention. So again, you have a few rich countries that are very focused on climate. You have a US which is not really focused on, and of course you have a very large poor or poorer world, China, India, Africa, that are just much, much more focused on getting rich and that is getting more energy. So we really have a very big difference between what most people in the world are C concerned about and this climate conversation that we've had. Just one more thing, you also asked what was the impact on the security. And as Dan also mentioned, it has been very clear for Europe that you can have lots of solar and wind if you have lots of gas as Arun also mentioned. But you really do need that gas and we got it from from Russia that turned out to be really energy unsecure. And so again, we need to go back and say what makes you secure is, for instance, what the US has ma managed to do to have fracking and get lots of gas cheaply.

- Well let's pick up on that Dan, you mentioned briefly about the geopolitics, but this is a tremendous change in the geopolitics from tremendous from basically the Midea and Saudi Arabia and OPEC being the swing producer to basically shale here having an important impact on the geopolitics. And maybe you could pick up on that and how in an era now we're worried about Russia and China and great power competition again, some people even called it, you know, cold War 2.0 hopefully that's a little, hopefully that won't, won't really continue. But we certainly are worried about that. So how do you see how it's gone on in energy around the world, but importantly in the United States affecting geopolitics? Well first I have to

- Say, you know, I wrote my very first book on the Soviet American Cold War, the Cold War. Now I call it the Soviet American Cold War to differentiate it from what's going on right now, which is, it's not a cold war in a sense 'cause you're highly in highly integrated economies, which was not the case with the Soviet Union. But it is those geopolitical considerations of energy loom very large Bjorn has already referred to to it. And I have that the absolute significance of us shale gas. You know, I was just talking last night to the, a deputy chairman of an European energy company who said everybody in Europe's against shale, but it was shale gas that saved Europe and really has saved Ukraine because otherwise without those imports of us, LNG Europe could not have withstood the economic pressure 'cause Putin was trying to use the energy weapon. He calculated it would work, he miscalculated 'cause he didn't realize what the US could do. So I think it has great geopolitical significance. The Chinese are very sensitive to energy, they import 75% of their oil. They worry about that in terms of rising tension. And so that I think is maybe the number one driver, not climate for their diversification and their push for electric cars among other things. So energy continues to be very geopolitical. There's one big question out there, Michael, with there we're kind of reaching a peak in terms of US shale its growth and therefore where will you meet the, the growth? And we just had this huge turnaround from the International Energy Agency, which had, as Bjorn knows very well in a room this 2021 scenario of net zero by 2050. And suddenly they come out with a report saying that every year between now and 2050 you need $540 billion in new oil and gas investment just to keep the world running. That is a big change, $540 billion a year of investment. And that's from the International Energy Agency.

- Yeah, that's, that's a really important information Dan, we'll get back to innovation and investment and longer term horizons and policy flip-flops affecting that in a minute. But Arun, you've written a lot about the, this intersection of energy and environment and national security and economic security. If you wanna pick up on that at all, please do.

- Yeah, I think, you know, in my paper, the Hoover paper on, you know, how do you balance the policy to balance the imperatives of national security, economic security, and environment security? I think one has to really look at it in timescales. It, it is very important to look at it short term, midterm long term. If you have a national security crisis today and you have to use oil and gas, you will use oil and gas. And that's kind of the, that's a practical way to do it. Otherwise you have a national security or an economic security. But at the same time, we cannot forget the long term. And I think the long term is that you have to develop policies and the, by the way, the last thing the business community wants is fluctuating government policy that is really bad. And what you really need is the stability in the policy that incorporates the, in any environmental impact of the short-term thing. So in the long term you actually take care of it so that you balance out. So I think this midterm short, the short-term, midterm long-term is the way, at least I think about it. And, and so that you are practically pragmatic in addressing all the three securities.

- Well I think that's an important point for everybody to keep in mind. We don't wanna lose sight about that long run. Although, as Dan is suggesting, and perhaps Bjorn is also suggesting it may be stretched out a little bit in the early optimism head.

- Are you just saying a little bit?

- Well, I mean okay. For sure. A few decades more. Absolutely. Okay, so let's go on then on this theme of what works and what will generate that innovation. We need to drive the cost down, have various things scale with two, two important points. And first, Dan, maybe you could just say a word about the scale of energy. Do you go, I think most people aren't aware, they don't think in quadrillion this and terabytes of that and trillion trillion of this. So, well it's, if you've got some sense of how gigantic

- Well I got, I, I mean that the energy, you know, the total world consumption of energy is huge and people don't realize that it's the foundation for everything else. That there's no nothing. You know, our society doesn't work, we go back to the 16th century otherwise without it. And I think that that was, you know, in that foreign affairs article you mentioned identified about seven reasons that the energy transition is not turning out the way that was predicted five years ago during COVID, when demand went down and prices went down. And the starting point is simply the scale of the energy system. The energy system that supports, what is it, $115 trillion world economy. It doesn't, you can't change it that quickly. I went back and in my book the New Map and looked back at all the other energy transitions they took a long time. So there was almost a degree of hubris saying that you could transform the energy system of $115 trillion world economy that might be 200 or $250 trillion in 25 years that you could transform it in in 25 years. It was just, I think that was the first, the first sort of overstatement that underlied every underlay, everything else.

- Now would you think that one of the lazy analyses was that we were gonna replace fossil fuels rather than add to them and have Yeah, exactly. Of growth coming?

- Yeah, I mean that's, you know, I think when you look at it you say, okay, wind and solar's grown a lot from a small base, but it's grown a lot. It's 18% of China's electricity now, but conventional energy's grown a lot too, and at the same time continues to grow. So really need to think in terms of energy addition rather than just energy transition. And I was struck in, you know, in the, in the golden state of California, the head of the state energy committee in the state assembly just recently said, we've run outta magic wands. And even I love the quote from Gavin Newsom who said, we are all the beneficiaries of oil and gas. No one is naive about that. It's just kind of, that's where thinking is catching up with the complexity of this global energy system we have.

- Pierre, let's turn to you because you've looked at a lot of these different policies and we saw a lot of the policies, however well-intentioned, maybe overly optimistic in the potential outcomes there were very costly enacted and there a lot of them were subsidies for various types of green energy mandates for use, attempts to make it more difficult, refusal to allow pipelines and things of this sort looking in the US and there's, there's been a study of many of these around the world. What's your sense of how, how effective they've been and what's your sense of where where a real serious long run solution might lie?

- Well the real problem here is that the west, so the US and all the rest of the rich world matters very little in the 21st century. And I think that's one of the things we keep forgetting. I mean Dan was pointing out the world economy is huge, but most of the energy use in the 21st century, the vast majority of carbon emissions are gonna happen in the not west, so not in the us in the EU and Canada, Australia and so on. So one scenario, obviously it's hard to predict into the future, but one scenario that's very popular sort of suggests that the rest of the 21st century will be about 14% US and other rich western world emissions and the rest come from China, India, Africa and so on. And so even if the whole rich world, so not just the EU but also the US and everyone else actually went net zero by 2050, it would matter almost nothing. If you try to run the two different things, one, the, the US and the EU just keep their policies as they were a couple years ago, or one where they go net zero by 2050, the difference in the UN climate model shows that this is a difference in temperature by the end of the century, about 0.2 degree Fahrenheit or 0.1 degree centigrade. It's just not gonna matter. We won't even be able to measure it by the end of the century. And what that really shows us is, and I think that was also what Dan was alluding to, is what matters is what the rest of the world does. So first of all, it's very, very hard to keep having consumers and voters accept high and high prices. That's what they're learning in California. And that's certainly also what we're seeing in Europe when the UK and Germany and many others are seeing incredibly high prices because of all the policies that you just talked about that is unsustainable in a political sense, but also even if it were to succeed, it's just not what's gonna matter for the rest of the 21st century. So I think it goes back to what Arun was really pointing out in the short run, you really can't do anything but the long run. You can only cut carbon emissions and get people to at least somewhat transition. If you get innovation that makes green energy cheaper than fossil fuels, it's just not gonna happen. If you have much, much more expensive green energy, voters are just gonna say no.

- Yeah, I would say two things about that and me, what I wanna comment on first is a lot of the analysis, just for example, I'm looking at electric vehicles looks just so what comes outta the tailpipe and doesn't do a full cycle analysis. And it seems to me that is one of the problems that we have to look from really where the materials are mined, what methods are being used, how they're pr, how they're processed, how they're shipped, how they're deployed, et cetera. And not just what comes out the tailpipe to use an electric vehicle for example. And it seems to me that that's a difficult concept to get across the public who may, maybe they put solar panels on the roof and they're getting subsidizing this is great and they don't understand either the scale or the need, need to understand that somebody's paying earlier in the chain or some somewhere some size. Could I di dive in on

- That point?

- Sure.

- Just for a second because I've been working on that Right now we're doing a study called Copper in the age of ai, electrification energy transition. A lot of it's about electrification. An electric car uses 2.7 times more copper than a conventional car. Ai. You can need a lot more in this system. There's a problem which is the, the supply as you say, of the raw materials of copper. It takes on average 16 years to open a new mine in the world, 29 years in the United States. And and yet when you look at all the numbers, including China's incredible advance of electric cars and batteries and everything, you know you got a double copper production. But just how that's gonna happen. And I think that was one of the other things that was not taken into account. And then thinking about energy transition, is that material constraint on it where it collides with something else, which is the geopolitical clash between the United States and China, which is playing out exactly right now on rare earth because of China's predominant position in all of those mineral supply chains.

- Or you wanna pick up on that? Maybe you could talk about, yeah, how dependent we are, what timeframe we could and what we need to do to change that to get those supplies made available. Yeah. That that's consistent with our national security and our economic security.

- Sure ha, happy to say, but just to want to point out that I think what B beyond is saying, and I completely agree with that, after solving 10 different differential equations, it comes down to cleaner must be cheaper. And that's a research r and d technological innovation, industrialization the right way. So I, I really wanna point out that I think there's a real need for government r and d to really bring down to outcompete other nations that are competing with us in, in terms of whether it's supply chain or others. And we can go into more detail, but I think that is the goal and, and I think aft and initially any new technology to be competitive needs a little bit of help to come down the learning curve and that's fine, but eventually it has to be market based and has to be cost competitive. So I just wanted to kind of point that out in terms of the copper, I couldn't agree more what Dan is saying that as you electrify things in general you'll need more copper. However, what also has to be accounted for is, and this is going in the engineering side, is the voltage, if you use higher and higher voltage, you need less copper because you, your current flow goes down. So that's why if you look at the grid that's going on that is being built in China, they're not operating at in a hundreds of kilovolts in the United States, the highest voltage is 7 65 kilovolts. They are operating at 1.1 mega volts and they wa they're testing out 1.4 mega volts because you need less metal. So you definitely need more copper but you also can operate and that's technology that's call Arun

- In the transmission lines. Don't they mainly use aluminum?

- No, they use copper. And now we can get into the reconductoring

- Because we use mostly aluminum in our long use. You spell as that copper

- And copper,

- I mean copper in the distribution and

- Yeah but even in the, in the data center for example, the architecture of this, they use copper is used up there. But if you look at the architecture, if you go to higher voltages you actually need less copper. And so, and if you could get the voltage to the chip, the chip, you operate at few volts but you need a data, you need technology to drop down from a DC voltage of tens of kilovolts to down to a few volts. And that is power electronics technology. And that is based on silicon for sure. But silicon carbide, gallim nitride and the United States is the biggest producer of silicon carbide. And so I think there's a lot of opportunities out there to innovate as well. But Michael, you asked about the supply chain and there are multiple factors out here. I mean whether it's, you know, lithium supply chain, we got to develop, you know, local supply chain out here. There's no question about it. But in terms of the supply chain for, for example, nuclear fuels, we will buy a nuclear fuels from Russia and Kazakhstan and we don't, we need to build that supply chain out here. But we just ran a workshop actually with Hoover in, in Washington DC on graphite. And graphite is not only used for, for you know, for lithion batteries but also used as arc furnaces and arc furnaces for steel making. And what we found is that most of the graphite we buy today, 99% is from China. And if you want to use, replicate their technology out here, we'll never be able to complete compete. And so one needs to then out innovate and come out cheaper so that you can actually build a supply chain out here and that requires r and d that requires new ways of making synthetic graphite. And so this is just one example and I think you can go for magnets and all of that and all the various technologies that I think we need to have supply chains with the, the biggest component, the security part of it. We have to have some domestic or French shoring these technologies.

- That's important to point out. Bjorn, you've, you've long said, long said innovation is really key. Maybe you could pick up on that. Are there some promises, maybe it's medium or longer term for decarbonization that we're not really getting enough attention that don't seem like over promises they may have been hoped for to come more quickly, but what would you say is some of the leading candidates for innovation in the future that we should be paying attention to in addition to all the things or maybe including all the things that are in set?

- So you're looking for investor tips, huh? Well the truth is I don't think any of us really know what's gonna power the rest of the 21st century. And, and and, and that sort of is inherent in innovation. We don't know where that could lead, but what we do know, and as Arun pointed out, we do need to have green energy that's cheaper otherwise, you know, most people are just not gonna pick it. We'll have a few rich well-meaning countries that will do some of their emissions from green energy technologies. For the rest we'll just simply focus on getting more energy. If we could make green energy cheaper than fossil fuels, eventually everyone would switch. So as Dan pointed out, nuclear is certainly one option. We we're talking about fourth generation nuclear, these would be small modular reactors possibly that could be type certified at the factory. So instead of what we're currently doing, and that's one of the reasons as Arun pointed out, that we're seeing negative learning or increase in cost for, for nuclear. That each nuclear power plant right now is being built as this, you know, opera house. That's just this one unique place where we have to get everything right and everything just so, which of course makes it incredibly expensive. But imagine if we could type certify at the, at the factory and then we could just ship out tens of thousands of these nuclear reactors in like a container size that could dramatically change the world around. Remember the only time when the world has really decarbonized more was during 1970 to 2000 when we had lots of nuclear being faced in, in France and many other places. This is the kind of way that we know could work. Again, we don't know whether fourth generation nuclear is gonna be cheaper than fossil fuels. Remember the other three generations were promised to be incredibly cheap and of course that didn't turn out, but what we should do is invest a lot more in research and development to see if that promise comes, comes true. It could also be geothermal. There's a lot of chatter around geothermal. We have lots of power essentially lying beneath our our feet and because of fracking we now know how to drill much better. So potentially that could be incredibly cheap and again also deliver power 24 7. One of the things we haven't really talked about, but the big problem with solar and wind of course is that they're unreliable. They, you know, we can't really determine when we get our asana, when we get our wind power and we need power 24 7, which is one of the reasons why we need gas as backup. So if we could get these 24 7 power sources like geothermal, that could be a solution. Batteries could potentially also be positioned forward, but it's gonna require much, much more than what we have right now. So I'm a little skeptical about that. And of course there's fusion, which is sort of the, the golden chalice, is that the right word? But you know, sort of the, the thing that we're all hoping would eventually happen and that happens in all the the sci sci-fi movies. But again, we don't know whether that's gonna happen. We should be spending money on all of these things because I don't know which one is gonna take over and power the 21st century. I don't think anyone knows. But it's very, very cheap to do r and d on all of these areas. Much, much cheaper than our current climate policies and much more likely to work in the long run.

- You know, graphite was mentioned, I noticed the other day that Exxon announced that it's getting into the graphite business. So we have some,

- And it's already announced that it's going into the lithium business.

- Yeah. So it's really, really an interesting, we'll see one of our leading multinational companies that's been a leader in oil and gas start thinking about these kinds of things and how they're gonna affect the entire energy ecosystem down

- The road. You know, if I could say the point that both Bjorn and Arun made is about the importance of r and d and and time I, as Arun was speaking, I was thinking it took about 30 years for solar to get commercial. It took about 30 years for this thing that absolutely could not work. It was all the textbooks said wouldn't work shale to actually prove that it could work. And so I, you know, I think both of them are saying that the most, maybe the single most important investment you can make is the investment in, in research, in science, in technology and maintaining that. And that system is under stress right now. And universities, research labs, they have a really critical role. They won't come up with the answer tomorrow, but the, what's the work that's done today? Because somebody is obsessed or some group is obsessed can have a big impact as Bjorn says in 25 years. So I think the, the flow of research money is absolutely critical underpinning of this whole discussion.

- I to just add, we do this all the time, this is the economic argument for research and development. There's a, there's a constant underinvestment in the research and development across the world because it's very hard to do big innovation that's gonna have an impact 40 years down the line because your patent will ever run out. So e essentially it's gonna be good for humanity but it's not gonna be good for your business and that's why you don't invest in it. Remember we do this all the time in medical research because we recognize that it's a good idea to spend lots of money on researchers who then investigate stuff that 40 years down the line turns into a patentable pill or injection that companies, pharmaceutical companies will get rich from. But that we will survive longer with, we should do the same for energy and we're just

- Not ru is right in the middle of that, in that whole issue knows that firsthand what's happening.

- So I was gonna turn to you to get some perspective. Obviously you're a leader in what's going on Stanford and leading university research institution, especially in this area. And others say this should go on in government inside the government for national security as others say, well it should be done in the private sector with greatly enhanced RD tax credits. What's your view about how we balance all that out as we move forward

- And in the, and there needs to be feedback loops, which is why the engagement between universities and the industry is so important because the feedback loop has to be, has to be feeding each other in a very positive way. I think the government's role as was pointed out so well is certainly to fund the r and d that is pre-competitive and an all of the above approach so that the university's and national labs are investing in ways to not only do things differently but eventually bring down the cost and make cleaner cheaper, right? So that's one the government's role is also to create the right policies where the industry can not only pick up these technologies and scale them, the universities don't scale national labs don't scale and scale is super important on this and, and scale them but have the right, you know, price for the externalities. And I go back to George Schultz and Schultz Baker approach. If there's an externality externality, which there is in terms of CO2 price, it let there be market-based approaches to to do so and we haven't gotten gotten there. And the other thing the government can do, which I would add to the Schultz maker thing in terms of r and d and the externality pricing is now we are seeing the biggest challenge is the permitting reform that is needed because otherwise we are stymied, we can't build anything in the US And so that's the other role for government is to streamline that and make sure that things can be built because we need to build things, whether it's for AI data centers for or other things, we need to be able to build this. So the role of the government on this fund r and d, if, if there are external externalities from environmental and climate point of view, price them so that there's market-based approaches and have sensible regulatory approaches to make sure that the public good is maintained. But it shouldn't take five to 10 years to build a single transmission line that is just unacceptable.

- Well I, I think we will all agree on that score but also worry that we have these big swings from administration, administration, we support a pipeline which we, we stop it, et cetera. It makes it very hard to do long run investment if you're a private firm. Dan, maybe you could pick up on that about the, the cost to the instability of the policies and how they're affecting long run business decisions to be. Well I can

- Certainly see it in terms of the commitments that companies make. This company I know that was seeking to build a transmission line to bring wind energy from Kansas to the upper Midwest and it was supported by the last, doesn't seem to be going forward at all. Lots of local opposition of the kind of RO talks about judicial reviews and so forth. And so it does make it much more difficult to, to make those investment decisions when there isn't a certain sense of a, you know, to borrow a phrase from Bjo and organization a consensus about it because you know, these investment decisions have a much longer life extension than that of a four, even an eight year administration. So the tendency becomes to disinvest and that's what's happening in California right now because of policies.

- Absolutely. Actually we're starting to see a change. And again as I mentioned earlier, whether this is for his own potential presidential bid or not, we've seen the policy change to sort of lighten some of the regulatory load that started with housing and now it's headed into well and,

- And I think the point that Bjorn made about price is really important. If you look at those new kind of populous parties in Europe, which Bjorn would be more familiar with this, I mean immigration's their number one issue, but high energy prices related to climate policy seems to be the other one. And if you take Europe right now it's going, it's supposed to increase defense spending to 5% of GTP. It has this huge problem about competitiveness that it's lacking competitiveness and yet, so it's going to have to, you know, has only, and yet the governments are under huge financial strain. So it's gonna have to re whatever the goals are, it's going to have to redirect funding 'cause it just doesn't have the Lars to do every single thing that it wants to do.

- Absolutely. These important trade-offs and as Arun you mentioned harmonizing national security, economic growth and environmental stewardship is a tough act, but it's something that has to be done in a lot of trade-offs. Bjorn, I think we, we seem to be talking, haven't said explicitly yet that the government trying to pick winners and losers isn't usually a very good idea that maybe investing in generic pre-competitive techno technology r and d is a good thing. And then we turn over the marketplace and let everyone compete on a neutral level maybe. And I think Arun was referring to a revenue neutral carbon tax as a, even though the word tax is very unpopular, it's a way to put a price on an externality. But in any event, would you care to comment on that on the, the attempts government have made to kick winners and losers and what the outcome so far seems to have been?

- Yes, Michael, it's never a good idea to government decide what should be the winners and losers. And, and so I think it goes back to what Dan started out saying. Energy really underlies pretty much all of our e economy across the world. And, and so you can't have politicians toiling about and and deciding what should deliver that power, what should deliver that energy. That's a very bad idea. What you can have politicians do is to decide what should power in the future because we're gonna make sure that that becomes a cheaper option. So by all means, I mean, Arun, I love your optimism that we can get sort of a, a good carbon tax on, on everything. It hasn't had a very easy life journey so far. But, you know, economists would tend to say that's the right way to think about it. But I think really what's gonna solve this problem is if you can find some energy source that's just so obviously cheaper that it doesn't really matter whether you got the externality price price right or not. We saw that very clearly with the shale revolution in the us which I think was sort of a, a good example of what happens when you come up with a technology that just dramatically undercuts everything else. Remember this was not intended at all as a climate policy. You know, it was funded by George Bush and many, many others. But the fundamental point was just to get more energy, but it just so happens to make gas much cheaper than coal and gas emits about half as much CO2 as as coal. So it just dramatically dropped the US emissions of CO2 because the US switched from a large part from coal to gas. So if you have an innovation that just makes one thing cheaper and preferably one that's green, you will see a switch. I mean in that sense, we should have everyone else around the world fracking because it's a technology we already know works and then of course we should move on. That's the way you go. So politicians should stay out of saying what's the right technology, but they should be funding lots and lots of research and development into green energy so that we will get more of these fracking revolutions and get that happening everywhere around the world.

- We could stick with fracking for a second in shale. Dan Aro. Is there some reason why we haven't seen an explosion of fracking all over the world? And obviously you need the ge the geology to be right and the,

- Well, I think I can jump in there at least in part of it. I mean you are seeing it in Argentina right now where there is some confidence that you'll be able to make investment and still, you know, recoup, you know, your investment. But I was talking again to a company yesterday that there's opportunities in Europe, but it's a ideological, almost religious opposition to the idea of fracking. It's just the brand is so bad in Europe, but of course the US was particularly the geology was particularly open to it. But there's, you know, and you had an ecosystem and you had independence, you had entrepreneurs, so you haven't seen a take off much elsewhere. And certainly in Europe it's, it's a no-no.

- Arun, do we know anything about where it's the geology might be conducive and if the policies change, there's more stability, the investment climate improved where fracking could make a major leap forward in some other parts of the world?

- Well I think that if I'm not mistaken, and I could be wrong, I think the biggest reserves of shale are in China and, but in addition to the reserves, you also need water. And I think where the reserves are and water is an issue and,

- And the geology and the geology I think is most the

- Geology. So, so the geology is there for the shale, but I could be wrong about this, but I think the availability of water is, is a critical need. I, I just want to, if, if you don't mind Michael, just touch upon something that, that Bo Bjorn said, I think the growth, the energy growth is not going to be uniform across the world. India for example, you mentioned that and I agree with you, it's got a massive growth coming because just economic growth and the population is the largest population is still growing a little bit, but it's tapering off. I think they've, they are importing oil because from Russia now because they don't have oil reserves out there and I think their transition to electrification of transportation, they've already done that in the rail. They wanna do that in the transportation is frankly e economic security issue and a national security issue because they would like to, you know, transition so that they can generate their own electricity and you know, essentially fuel the electric vehicles. So I think in some cases the alignment of national security and cleaner technology is there is, and I think one should leverage that opportunity to really provide the security and you know, cleaner can be cheaper but Tina can also be secure, more secure.

- Arun mentions India and this goes back to the basic 2050 net zero goal two As as Bjo and has said two of the three largest emitters, China and India do not have 2050 goals. They have 2060 goals, 2070 goals. Britain has a 2050 goal spending a lot of money on it. Britain's emissions are 3% of China's. What Britain does will not really have much effect. And I do wanna mention one technology that is having a big impact only very recently on the energy system, but in terms of promoting demand and that is where you start at Michael, which is ai, which is suddenly utilities, which for 25 years did not need to think about demand growth are trying to figure out how to do it. And one of the consequences of that is that it's bringing more gas to the system. It's fascinating to listen to Arun about what the technology of the voltage in the data centers and maybe maybe some of the expectations for the growth of electricity demand are exaggerated. But we see at least US electricity demand for data centers going from 4% to 10 or 11 or 12% in five years. Maybe that won't happen. But that's an example of the technology having a big impact but not in the way you are in terms of new supply but rather creating new demand.

- Absolutely. India, we were just talking about India. India has announced it's going to a national AI policy wanting to be a AI hubs and AI centers and so on. And obviously they're gonna need a lot of electricity and depend it's not just having the electricity, it's a massive amount required at peak and then it comes up and down depending on whether you're training, you're inferencing, et cetera, and ai. So

- It's a big challenge. They're investing heavily in solar and wind. They're primarily based on coal today and

- Yeah the young for coal, they can

- And they're open now this is terrific to hear. There was a Hoover team that actually went up there to talk about nuclear and actually that is very refreshing to hear that they really wanna lean into that as well.

- And I think a lot of places also think of this as a national security problem.

- That's right.

- We mentioned China and it's immense investment in AI and some people would say they're doing really well in some parts of it and maybe not in others and that the US has to stay ahead. But you see countries in the Middle East, countries in Europe, countries in Asia, all announcing big ambitions with respect to ai. Some of see an economic issue, some of the national security issue, some seem just don't want to get left behind and they're not absolutely sure and of course none of us can, as Jorn was emphasized, none of us can really know where this is gonna be 10, 20, 30 years in the future. But we know that this is gonna be boosting demand for quite some time. There was an estimate by JP Morgan the other day that a sizable, you know, a quarter to a third of economic growth last quarter was an AI data center build out. So this is a, this is a non-trivial thing and it's really sparking something heavily in the us it's already been going on in China and it's, it's spreading globally. So I think think what

- Michael wearing your economist hat, isn't it pretty clear that the AI boom is, is almost more important than what's happened to consumer demand right now for economic growth in the us?

- Well it's certainly on a par, let's put it that way. We don't want consumers to collapse. That would be really bad for the economy. Yeah, but the ai AI data center demand is really, really a big tailwind of the economy for at least for the next half dozen years. Where it winds up with the technology is where Microsoft and Meta and Oracle and all these companies, what technologies they use to get the electricity, how, what's co-located, what's gas turbine, what's fuel cells, what's other technology, small modular reactors as Bjorn was mentioning, remains to be seen. How all that plays out. I think they're gonna try different things and in different sites it may be somewhat different depending on the factors that Dan Arun have been mentioning. What makes the most sense,

- Michael, if I could just because one of the things that are incredibly important, especially for AI centers is they want power 24 7, you're right, they do need to scale up and down but fundamentally need, they need this power 24 7. Oh, absolutely. And so while, while we can certainly talk about both India and, and China increasing their solar and wind and they are, they're also just gonna say, I mean a, a large part Stan also pointed out is just simply to be less vulnerable to oil when they switch shrinks and sell electric cars. But at the end of the day, if they can't get 24 7 with solar and wind, which is gonna be very hard and they don't have enough gas, they will go back to coal because they do have lots and lots of coal and, and so I really think if anything this, this sort of pushes forward are need to get this new innovation that'll actually fix not having everyone revert to coal.

- Well you mentioned coal and that leads to geopolitics and energy mix and it's important to note that Germany, for example, for a while it was importing ignite because they wouldn't do nuclear and Entrepr Merkel shut down nuclear had very, very substantial renewables commitments. There were issues with the grid and they wound up importing coal. So I think Bjorn, your, we've all emphasized this, but I think you just made summarized it greatly that whatever's gonna work is gonna happen. And that's based heavily on economics. Whatever our longer term needs are, people in the shorter term are gonna, whether that's firms or governments are gonna do what they need to do to make it happen.

- You know, also add that I think, you know, in, especially in India, when you see fluctuation that is managed today by hydro, and I think hydro provides a big balancing in a service, which I don't know if, if you recall when COVID happened, the prime minister said that, you know, we should turn off the lights just in remembrance of people who are suffering and turn on their, the camels for a little while and they turn off the lights and actually there was a big drop in the power and the only way they could manage it in this sudden drop of power was by modulating the hydro. So I think hydro plays a big role. Now, of course Germany, I'm not sure how much hydro is there, but Switzerland is all hydro. And one you, you might, you'll know this better than I do. So I, I, I think that's another technology and as was pointed out in terms of base load technology, geothermal is something that we should be really looking at carefully. One of the bleeding edge companies in that came out of Stanford called vo, which is now with Google and all to provide geothermal electricity for data centers. And so I think that's the other option for Baseload power. You do need something baseload in addition to, you know, you know, solar and wind. But I think there's a lot of penetration and investment going on solar wind with the diurnal variation being managed by storage right now in California, Texas and other places.

- So that's, I think, I think Michael, I think I just heard you utter what we can call the Baskin axiom. You said, I wrote it down, whatever works you said it will happen. Ash phrase

- Where we have, we have lots of business firms competing here and around the world, we have governments making policies, et cetera, but in the end they have to keep the citizenry happy, they have to prevent prices from becoming so high that there's a revolt as beyond was saying some of which is going on as Stan mentioned in Europe. Certainly in California people are upset about it and there's a lot of pushback. So there's a lot going on. But maybe we can conclude with a little bit about final, final word on politics and geopolitics. We mentioned this 180 shift from one administration to another and so on. And it's important to have stability if our firms can plan for the long-term investment. So I guess I would ask on the political front, do you see any reason why we could be optimistic that we won't be bouncing back and forth in competing ways depending on which parties in power and the, like that we can get some stability here or elsewhere in the world? Do we see some capability of having a political enough consensus to do a variety of things? Whether that's permitting reform, whether that's, you know, higher voltage grids that may, may be people not wanting their neighborhoods, et cetera, all these things. Do we see some ability to generate that or to, to use a phrase that wanted you used earlier so that we could have a political consensus that's sustainable Because we see in the public opinion polls whenever there's an economic problem, concerns about the environment plummet to the bottom, people are, you know, economic concerns just force everything else in that situation. So the question is, do you have any thoughts about how we might do that? And we, we'll, and I'll ask one more question about the geopolitics of it all.

- I think fundamentally what happened with the GLO global warming conversation was that it became so end of the world that that, you know, in the US one party, but in the rest of the world, many parties went along with this end of the world sense. So we had to do everything, we had to throw everything in the kitchen sink at this problem. And that means a very, very wide shift from administration to administration. If you one that sort of says it's the end of the world, you'll have sort of a Trump administration coming in and saying, oh, we're not gonna believe it at all. I think if we could get back to a sensible sort of middle of the road sort of understanding as you point out permitting reform, I think there would be a lot of political understanding for that. And then a sensible approach. And I think one of the things that we've kept referring to here is get lots more r and d. So green r and d is something that's both incredibly cheap compared to climate policies and will actually deliver a lot of other things as they, you know, somewhat incorrectly said, you know, we sent a man to the moon but we got Velcro. That you'll also get other innovations out of this kind of thing that you'll get you know better batteries for your cell phone, which will be great. So I think we could spend money on r and d and get a wide political sense of consensus on that, and that would help a long way. So stop this end of the world, which is not correct and stop the not happening at all and get sort of a sensible climate policy. Yet there is a long-term problem, but we can also solve it sensibly by spending a lot more on green r and d.

- Arun, you wanna pick up?

- Yeah, I would say that, I'll take a global view on this. I think every country starting from a different initial condition and there different constraints and they need to think about including the United States, the short term, midterm, long term, and from a security point of view, the economic security, national security, and the, and the environmental security. So I, I think the policies will be different, different parts of the world. And because they have their own imperatives out there. So I think from, from that point of view, if he could, th this is where, and I definitely don't want to make, I wanna make sure that the burden on climate is definitely on the G seven and, and maybe the G 20, but I don't want a country in Africa that is trying to get out of poverty to be burdened by climate policies because they have to live. They have to survive. So I think it is imperative that we take the climate policy and make sure that the biggest emitters come together. And actually, you know, at restaff, but I, something that we did not talk about, which I, I think is very important, is that the climate is, the weather is changing, the climate is changing, and there are extreme, the data is suggesting that the temperatures are reaching extremes. That has implications on food security, that has implications on water security, the heat security. And I think we really need to look at the climate adaptation part very carefully in addition to decarbonization. 'cause that may be more urgent than, than some of the other issues that we are dealing with because, and at the end of the day, I think a climate policy for the long term is, or, or energy policy for the long term that takes climate into account is really important. Any fluctuation is really bad for investments and long-term investment in infrastructure.

- Dan, I'll let you have a final word.

- Well, I think that, you know, we started talking about the importance of energy to the economy. And I think, and picking up on what both Arun and Bjorn have been talking about, that's very important for the developing world. If they don't have energy for development, then whatever our migration crises are now in Europe and North America, they're only going to get worse. And therefore you need an ecumenical approach. You need natural gas as part of the development. And I was, as Bjorn was talking, I was thinking, you know, things got so apocalyptic in one direction that you get that reaction in the other direction. You know, again, just so opposed where, what we've heard here is that more in the center, and I think that, I always go back, one of my favorite quotes from woods to Churchill, when he converted the Royal Navy from coal to oil, he said, safety and energy basically said oil. That energy buys a variety and variety alone. So we want diversification of energy supplies, not overdependence. We need that spending on an r and d and it that is such an small investment, relatively, but so important. And then you need, you know, a an atmosphere where these things can proceed and that climate is an issue, an important issue, but one of many, many other issues, which is exactly where Europe is now, and it's really in a tough position. So I think maybe at the end of the day, the most important thing here of all is some clear thinking.

- Well, I couldn't agree more of that, obviously. And I wanna thank all of you for this informative and indeed enlightening discussion about a variety of facts that lie at the heart of the Bates about energy and the environment. So Arun, Dan, and Bjorn, thank you so much for participating in this tandem bomb program on Fact-based policy podcast. If you'd like to learn more about this program, please go to hoover.org. If you have additional topics you would like to have us discuss, please send in, send them in, and we'll see if we can follow up in additional podcasts. And please go to hoover.org for informative essays, books, and podcasts about these important issues that we are producing in Thetan bomb program and elsewhere, Hoover, and please follow up as best you can. This is only the beginning of a long conversation that's going to have to happen in the US and Europe and India and China, everywhere else and among these nations as we move forward to eco a more prosperous economy, but also one that is consistent with some environmental stewardship. So thank you again, Arun, Dan, and beyond for this terrific conversation.

- Thank you, Michael. Thank you. Thanks for, nice to meet you. Yeah, likewise.

- Thanks. - You've been listening to Factual Foundations of Policy, a production of the Tandem Bomb program on fact-based policy where we conduct impartial investigations into the most controversial public policy issues facing Americans to read the essays discussed in the show, as well as other content, including episodes in this podcast series and other engaging, accessible and educational content in written video and audio formats. Visit visit hoover.org/tanenbaum.

RELATED SOURCES:

- B. Lomborg, Climate Change Is Not An Apocalyptic Threat- Let’s Address It Smartly, Hoover Press, Sept. 2024.

- D. Yergin, US Energy Security, Hoover Press, Sept. 2024.

- A. Majumdar, Energy Policies That Harmonize Three Securities, Hoover Press, Sept. 2024.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION:

- Prefer the podcast version? Subscribe here.