- Budget & Spending

- Economics

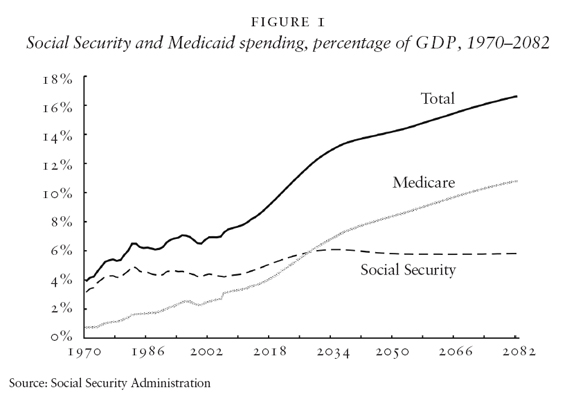

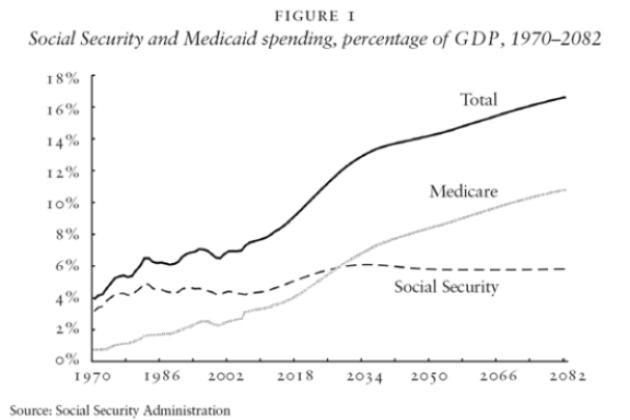

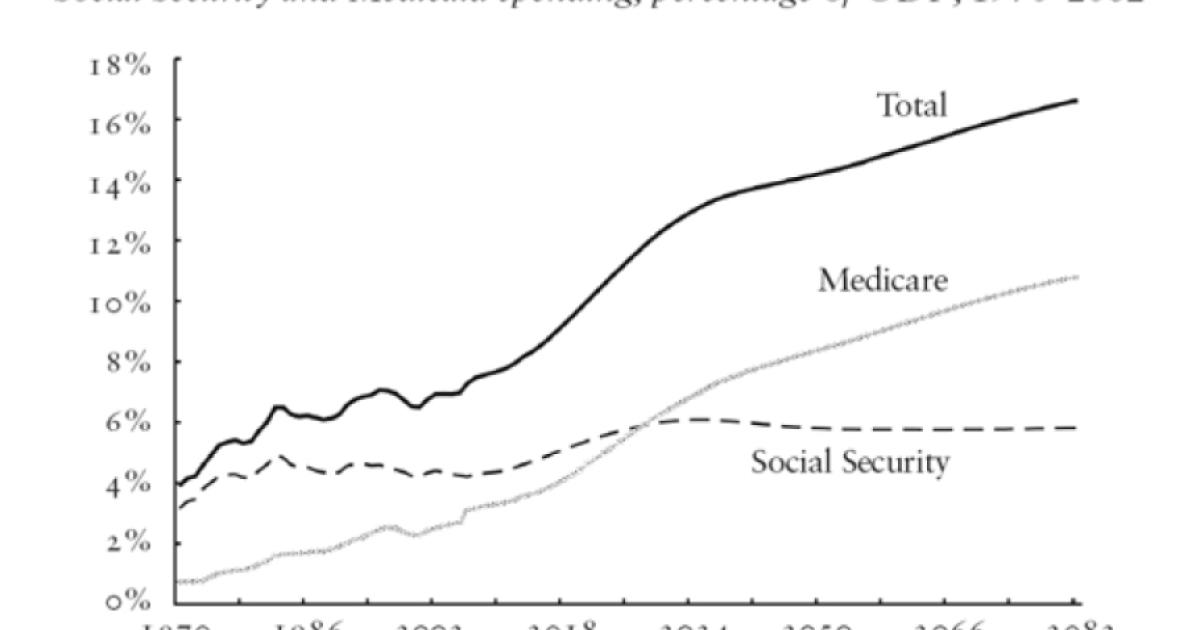

When politicians and policy wonks use the phrase “the looming entitlement crisis,” most listeners know exactly what that means: Social Security and Medicare. Spending on these programs is rampant, nearly $1 trillion in fiscal 2006, and is projected to grow exponentially over the coming decade.1 By 2082, due to the aging of baby boomers, rises in health-care expenses, and expected lower fertility rates, Social Security and Medicare are projected to cost nearly 18 percent of gdp — roughly what the entire federal government costs today. It is now common, if as yet unacted upon, wisdom in the Beltway that if the price of these programs is not reined in, Americans will have to suffer either substantial tax increases, unsustainable budget cuts, or both.

But the bad news does not end there. It turns out that Social Security and Medicare are not the only out-of-control federal entitlements. Two little known entitlement programs, Social Security Disability Insurance (ssdi) and Medicaid Long Term Care (ltc), are also increasing at unsustainable rates. Call these the forgotten entitlements.

These forgotten entitlements are already huge. Combined, they accounted for roughly $157 billion of federal spending in 2006, or nearly 6 percent of the federal budget.2 If they were combined they would comprise the fourth largest federal spending program, behind only Social Security pension payments, Medicare, and defense.3 These programs also suffer from unsustainable growth rates and threaten to widen the already critical long-term budget crisis.

But, to paraphrase Ronald Reagan, there is a pony in here somewhere. Social Security and Medicare present conservatives with a huge opportunity to show that our principles can be applied to make big government more effective while making individuals less dependent upon bureaucrats and politicians. The same mixture of traditionalist and libertarian approaches which underlay conservative social policy in the areas of education, health care, and retirement can be applied to reform the forgotten entitlements.

What are the forgotten entitlements?

Ssdi is a federal insurance program, funded by the payroll tax, that provides income to individuals who are under Social Security’s full retirement age but unable to work because of a disability. The word “disabled” triggers visions of quadriplegics and speechless stroke victims, but the actual definition applies to those with ailments far less severe. Indeed, today the vast majority of those awarded benefits suffer from chronic back pain, mental problems, and other difficult-to-diagnose maladies. Gaining access to the program, and staying in it, was made easier in the 1980s and 1990s by decisions that adopted less-stringent qualifying criteria and made other such changes. Jack Kemp’s famous truism — if you subsidize something, you get more of it — has proven true for ssdi. Disability is increasingly subsidized, and in the past decade, the number of ssdi beneficiaries has grown by over 2.5 million people. Program costs have also exploded and are projected to keep rising. According to the Social Security Administration (ssa) fy2006 report, ssdi shelled out $93.5 billion, accounting for roughly 16 percent of total Social Security spending. Many projections see cash benefits soon rising to $150< billion annually and sustaining over 6 percent of the adult population.4

Medicaid ltc helps elderly individuals pay for nursing homes and other institutional and community-based care. Not everyone can qualify: Only people with low incomes and few assets receive ltc benefits. But, as we will later discuss in detail, it is relatively easy for the middle class to “spend down” their assets and end their lives in a nursing home paid for by the federal government.

The looming Baby Boom-driven explosion in the population of the aged presents Medicaid ltc with an uneasy future. Currently, Medicaid accounts for 42 percent of ltc expenditures. Since Medicaid is a federal matching program, it can be difficult to calculate the federal government’s share in ltc services because matching rates differ from state to state. The average match rate, from year to year, however, is roughly 57 percent, which puts federal spending on ltc in fy 2006 at about $63.4 billion.5 Total spending on Medicaid ltc already has increased 100 percent between 1996 and 2006 to roughly $111 billion. With the total number of elderly people projected to more than double from 2000 to 2040, from 34.8 million to 77.2 million, similar increases are in store for the coming decades.6

How ssdi costs skyrocketed

The history of ssdi is typical of entitlements: What started as a narrow program to assist the hardest cases has expanded incrementally and is now overwhelming.

The first disability insurance payments were sent out in 1956. Originally intended for “totally and permanently disabled” persons, the payments were born from legislation Congress passed to provide early retirement for those who could not engage in “substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment which can be expected to result in death or to be of long-continued and indefinite duration.” Benefits were, at first, restricted to nearly retired persons, those whose ages were between 50 and 64. Then, in 1960, workers under the age of 50 were included. In 1965, the definition of disability was expanded to “include impairments expected to last at least a year.”7 In1973, reforms in health-care rules qualified di beneficiaries for Medicare after 24 months of disability.

These rapid expansions of benefits and eligible population had a predictable effect. By 1977, 2.8 million non-elderly people were on ssdi, a program whose expenditures by that time exceeded revenues by 25 percent. These looming financial problems led to federal legislation in 1980: Initial applications were scrutinized more closely, which increased benefit denial rates by 15.5 percent. The Reagan-led Social Security Administration also instituted more thorough and frequent disability reviews and made eligibility requirements more stringent, determining that 380,000 beneficiaries — or 40 percent of those reviewed — no longer met the program’s medical criteria.

A congressional backlash ensued, leading to new amendments in 1984 that expanded ssdi’s scope. Eligibility was extended to those without the “ability to function in a work like setting” — a drastic change from the program’s original, medical focus on whether an applicant’s diagnostic criteria “met or exceeded a listed impairment.”8 This opened the door to granting benefits for expensive, long-term impairments like back pain, arthritis, and mental disabilities, which affect an applicant’s ability to function in the workplace. The reforms did not actually change the definition of disabilities, but the focus of disability screening moved from medical to functional criteria, meaning hard-to-diagnose ailments such as pain and discomfort were considered. At its beginning, the Social Security Administration granted 93 percent of its initial ssdi awards for strictly medical purposes.9 In 1983, this rate still stood at 82 percent. In 2000, however, the number had dropped to only 58 percent.10

Congress has stacked the deck in favor of ssdi applicants in other ways, too. Medical evaluations provided by an applicant’s doctor take precedence over those conducted by ssdi program’s medical staff and hired independent doctors. Giving priority to the decisions of an applicant’s caretakers effectively renders powerless ssdi’s evaluation measures, especially on ambiguous conditions such as depression and back pain, which comprise a large portion of ssdi applications. To appeal a Social Security Administration decision is also relatively easy; in fact, three separate avenues of appeal are open to disappointed benefit seekers. Furthermore, appellants may use lawyers hired on a contingency-fee basis to help them prepare their cases; ssa, though, is restricted in its ability to retain and use outside counsel. And while disappointed applicants can keep appealing up the legal chain until some judge accepts their claims, ssa cannot appeal an approval of benefits that it believes was unfairly granted. And only 40 percent of granted appeals are for strictly medical purposes.

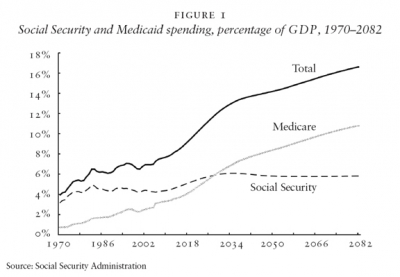

Thus, both enrollments and applicants have skyrocketed. In 1983, 3.8 million people received ssdi benefits, compared with over 8.9 million in 2007. The percentage of the labor force receiving ssdi benefits has doubled from 1983 to 2007, from 2.32 percent to 4.64 percent.11 Between 1996 and 2006 alone, the number of disabled workers and their dependents receiving benefits increased by over 2.5 million people.

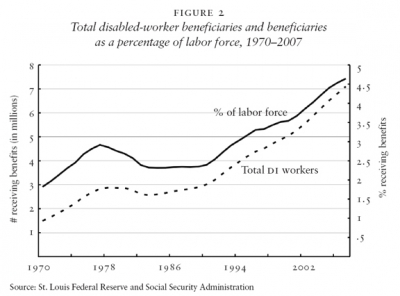

The importance of curbing ssdi can be seen when its caseload is compared to that of the most famous welfare program, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (afdc. afdc was the program by which single women with children received monthly checks and other benefits. It is what most people mean when they speak about welfare, and it was the program that the gop-led Congress rightly reformed in 1996. afdc was criticized in the 1980s and 1990s for allowing people who could work to remain idle; that the program did not require able-bodied recipients to seek and hold a job was considered to be a drain on the economy and bad for the people whom afdc was intended to help.

Today, ssdi is a larger problem than afdc was at its worst. During afdc’s peak caseload year, 1993, it supported 3.6 percent of the labor force. In 2007 the ssdi caseload supported over 4.6 percent of the labor force, and that number continues to grow. Nor are the costs of the two programs remotely comparable. In 1993, total spending on afdc equaled $31.1 billion in 2006 dollars.12 That is $62.4 billion dollars less than the nation spent on ssdi in 2006.

A rise in the after-tax income replacement rate for ssdi — i.e., a rise in the ratio of program benefits to the recipient’s former on-the-job earnings — and the increased numbers of women in the workforce (who are now workers eligible to receive ssdi) have surely contributed to the program’s caseload growth. But a recent estimate by Mark Duggan of the University of Maryland and Scott A. Imberman of the University of Houston notes that these factors account for only around a third of overall ssdi growth. The Duggan and Imberman study in fact determines that relaxed policy standards contributed to 53 percent of caseload growth for men and 38 percent for women. The ssdi caseload is also increasing because fewer people, once they start receiving benefits, ever stop receiving them. There are three main ways to “exit” the di rolls: The claimant may either reach full retirement age, die, or no longer meet the eligibility criteria. And today, even though many new ssdi recipients are more able-bodied than were their counterparts of decades past (the criteria for receiving benefits are now less stringent, remember), only 7.2 percent of ssdi recipients left the rolls in 2004 compared with 12.1 percent who left in 1985. Of those that exited in 2004, moreover, only 12percent did so for eligibility based reasons.13

These trends are rendered even more worrisome because funding for ssdi comes from the payroll tax — taxes that employers withhold from their workers’ pay. Of the total payroll tax, 15.2 percent is allocated to fund ssdi. As the ssdi caseload has risen, ssdi’s costs have exceeded its allotted percentage of the payroll tax. From 1985 to 2005, ssdi spending as a total percentage of Social Security ballooned from 10 percent to 17 percent. And every dollar allotted for ssdi comes out of Social Security pensions, which only worsens the forecast for America’s coming Social Security storm. Furthermore, ssdi is in financial turmoil. The program’s short-term financial solvency failed in the 2008 oasdi Trustees’ Report. Under the report’s high cost estimates, ssdi assets will be exhausted by 2017. In 2005, its costs exceeded the income excluding interest from the trust fund (di has a separate trust fund from Old Age and Survivors payments) for the first time. The trust fund includes the surplus funds that result when ssdi’s income exceeds its disbursements. Interest earned on the trust fund is then used to supplement disbursements. But in 2012, the costs are predicted to exceed income including interest from the trust fund, and in 2025, the di trust fund will be exhausted. Dramatic growth in payments, applicants, and enrollees has this program on the brink of collapse.

The ltc problem

Long-term care services are today a necessity for aging and disabled Americans. Historically, informal care — donated care by family members, friends, spouses, etc. — has provided Americans with help meeting their long-term needs. But many people no longer have the resources to care for their relatives or friends over a long period of time, and the elderly often need specialized assistance beyond the capacity of family members to provide. This is where ltc steps in.

Medicaid is the primary payer for ltc services — it pays over 42 percent of ltc costs. And ltc is a huge part of Medicaid’s budget: Though only 3.4 million people receive Medicaid ltc services, they were responsible for over 34 percent of Medicaid’s costs in 2007.14 The Kaiser Foundation has defined ltc as providing intermediate care for the mentally retarded, inpatient psychiatric services for individuals age 21 and under; other mental-health services for people age 65 and older; standard home health services; personal care; targeted case management; hospice; home and community-based care for the functionally disabled elderly; and services provided under home and community-based services waivers. Together, these services accounted for over $111 billion of the $303 billion spent by Medicaid in 2006. Federal spending paid for an estimated $63.4 billion of the $111 billion spent on ltc (states and local governments paid for the rest).

Medicaid’s income requirements are largely set by individual state programs. Most states have what is called a “Medically Needy Program” that allows an individual to pay a deductible — which is determined by subtracting the “Medically Needy Income Limit” from countable monthly income. The maximum income with which an individual can qualify is pegged at 100 percent of the Supplemental Security Income (ssi). ssi is a federal program that makes payments to low-income individuals who are either over 65 or are blind or disabled. Unlike ssdi, however, ssi is funded by U.S. Treasury general funds. Other states, called 209((b) states, have stricter rules about income and asset limitations that are also tied to ssi. In 2006, income test states — states that were not 209(b) or did not have Medically Needy Programs — set income Medicaid restrictions at 300 percent of ssi, which was $1,809 per month — i.e., applicants who made no more that $1,809 per month were eligible for Medicaid services.

But over the years, Medicaid ltc has become more readily available to middle-income citizens due to policy mechanisms that allow applicants to “spend down” their income and assets. Under this approach, certain assets, such as homes and cars, are not counted towards eligibility. People who could have otherwise paid for their long-term care have used estate planning, asset sheltering, and trusts to get Medicaid to foot the bill for them. It is fantasy to believe that Medicaid can continue to pick up all these tabs. Medicaid’s nominal expenditures for ltc have already grown by 305 percent since 1991 — an average growth rate of over 19 percent per year. There is also reason to believe that levels of informal care-giving will decrease. The costs of care-giving, rise in the female labor force, decreasing fertility rates, and high divorce rates mean that fewer avenues will be available for those in need of informal care. Average family size was only 3.1 in 2000, and is projected to fall to 2.8 by 2040.15 This, too, could spur further growth in demand for Medicaid ltc services, which would make spending skyrocket.

Private ltc insurance offers one way out of this trap. Many companies already market individual ltc policies, but so far, few consumers are buying them. In 2007, only 4 percent of ltc costs were covered by private ltc insurance programs. The Congressional Budget Office predicts that by 2020, only 17 percent of ltc costs will be covered by private policies.16 Why is the private market so small and why are consumers seemingly so uninterested in it?

One major reason is simply the availability of Medicaid. As mentioned previously, the ability for individuals to spend down their assets makes free Medicaid a viable option for many Americans, even those who are by no means impoverished. Additionally, an applicant who selects private insurance would not only be paying an otherwise unnecessary premium, but he would also forgo the value of the services provided by Medicaid. A recent paper by economists Jeffrey Brown and Amy Finkelstein illustrates the effects of this implicit tax that Medicaid places on private insurance — a tax that may be able to explain the lack of private insurance policies purchased for at least two-thirds and as much as 90 percent of the wealth distribution. Brown and Finkelstein show that for people who do not fall in the wealthiest ten percent of the population, the existence of Medicaid ltc affects their willingness to buy private policies.17 Plus, the limited size and newness of the private-insurance market means there is very little assurance that a private policy will cover all its holder’s long-term needs. Health care prices are rising sharply, so a private insurance company is forced to either charge exorbitant fees for a policy that can adapt to this changing health-care environment or offer a policy with sparser benefits.

Another reason the private market is so small is that there is a general lack of awareness about ltc needs and services. Few Americans plan for ltc needs, even though on average 69 percent of seniors will need ltc at some point in their lives.18 Because people don’t think about their future ltc needs, they don’t purchase private policies to cover them. By contrast, drivers are required to purchase car insurance, which creates a pool of safe and unsafe drivers from which the companies can collect rates and in which they can disperse risk. This keeps costs reasonable. But private markets for ltc are small, and ltc insurance buyers are generally those who will need and use their benefit — two reasons why private ltc insurance (worthwhile insurance, at least) costs a bundle and why Medicaid is so much more attractive.

Conservative principles are the answer

Describing these problems is one thing; doing something about them is quite another. Conservatives have often struggled with political approaches to domestic policy issues, understanding the tension between a pure devotion to individual liberty and the political reality and compassionate impulses which militate against a purely libertarian approach. By the mid-1990s, though, conservatives had settled on two complementary principles that combined the essential elements of libertarian and traditionalist thought. These principles finally allowed conservatives to talk about domestic policy issues such as social welfare, education, Social Security, and health care in an appealing fashion.

The first principle, largely traditionalist in nature, is that when government programs are established, their structure and administration should support and enhance traditional virtues (and certainly programs should never undermine such virtues). In practice, this means ensuring that government programs sustain and enhance attachment to the work force, encourage the cultivation of traditional moral virtues like self-reliance and ingenuity, and support rather than weaken the appeal of the traditional family. Welfare reform is the best example of this principle’s application: Welfare recipients are now told they must work, are supported in their efforts, and are not permitted to have recourse to permanent government support unless they are truly unable to function.

The second principle, largely libertarian in its impulse, is to require individuals to choose from among private providers of social services subject to minimum standards of quality. Government helps finance people’s ability to access these services through vouchers, tax credits, or personal savings accounts, but it does not seek to micromanage the providers, understanding that market actors can devise more effective and efficient services than can a slow-moving, politically bound bureaucracy. Giving the individual recipients choice among providers is also consistent with the traditionalist principle because it requires them to apply the same virtues they use in their daily lives and in their interactions with the private sector.

These two principles have united to undergird the prominent conservative domestic-policy initiatives of the last decade: welfare reform, school choice, Social Security personal accounts, and market-driven health care. Each initiative establishes clear traditional virtues as its linchpin and requires recipients to access and navigate the private sector to obtain their services.

Principles alone, though, are not enough. Successful reforms come only when principle meets expertise such that the reformed program will actually work in practice. Neither of us is an expert in ssdi or Medicaid policy, but by drawing upon the scholarship of policy experts and economists who are, we sketch out in the next section possible directions for reform.

Reforming ssdi

A traditionalist reform of ssdi could draw inspiration from the welfare-reform “help but hassle” model. Through the use of carrots and sticks, the program with which welfare reform replaced afdc, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (tanf), demanded that recipients prove that either they couldn’t work or they were actively seeking a job before it dispensed benefits. It provided job-search assistance and child-care subsidies, but it required even those who initially found private work difficult to continue their efforts and acquire and nurture those virtues needed to succeed.

Such a reform for ssdi would require the ssa to clean up the eligibility criteria and appeals process to help establish an expectation of work. To start, there must be strict guidelines about what is and is not a disability. Many people currently receiving ssdi probably can work, perhaps not full-time and perhaps not in their former careers, but nevertheless: They can work. ssdi’s failure to require those who can work to work has just as corrupting an influence on its recipients as did afdc. Furthermore, culture matters. As ssdi expands its definition of what constitutes a disability, more people have come to see work-related obstacles as disabilities and expect an entitlement to idleness. A firm, medical-based definition of disability can break these habits and cultures just as the firm work requirement in tanf did among single women with children.

An examination of ssdi’s growth in caseload illuminates the absolute necessity for policy changes that directly affect inflows of beneficiaries. David Autor of mit and Duggan have written excellent papers on the practicality and political feasibility of reforming eligibility criteria to address this problem. They suggest that eligibility criteria can be cleaned up by fixing the appeals process and placing a higher burden of proof for work unsuitability on those with “functional” disabilities. Autor and Duggan also show how a disability ranking system that allocates benefits according to level of disability may provide ssdi with much needed fiscal relief. Consider someone who is severely mentally challenged. There is very little chance such an individual will ever be able to work, which warrants a high rating on the disability scale, and, in turn, a high level of benefits. Someone with back pain or arthritis, however, will probably be able to work again — perhaps in a different capacity, but nonetheless working. This person’s lower disability rating means he would receive less generous benefits, have a higher burden of proof to claim his unsuitability to work, and undergo increased scrutiny of his efforts to find a job. And a ranking system would help ssa determine when claimants are able to return to work.

ssdi’s current appeals process is another problem. It undermines the ability to set a firm, medically based disability definition, and it must be reformed. Of those that are initially denied benefits, roughly 58 percent choose to appeal the decision — and of this group, nearly half are eventually awarded benefits.19 One effective reform would be to give equal weight to the opinion of government-hired doctors in any appeal at which benefits can be awarded. Another would permit the government to hire lawyers in any hearing before a judge. Both reforms would place the applicant and government on an equal footing in ascertaining whether benefits are appropriate.

Conservative ideas for Social Security reform also offer insight into how best to nudge people toward private disability insurance. For years conservatives have advocated a carve-out system, allowing individuals to take a portion of their payroll tax and put it in a private retirement account. The same principle can be applied to disability insurance. A system that allows individuals to carve out a portion of their payroll tax dedicated to ssdi and spend it on private insurance, purchased either individually or through an employer-sponsored group policy, might make private policies more affordable and alleviate the fiscal burden of ssdi disbursements. Alternatively, one can imagine rebating to employers the share of payroll taxes they currently pay which are earmarked for ssdi on the condition that those employers offer a meaningful long-term disability policy. Although we have no quantitative estimates of how this policy would impact ssdi or how much it would increase private policy purchases, the overall principle provides a framework for future study and reform.

This two-pronged approach — setting stricter standards for qualification and promoting the use of private insurance — translates conservative principles into practical ways to encourage and enable workers and stimulate market-based disability insurance.

Reforming ltc

Medicaid ltc is a tougher nut to crack. Its benefits are more pervasive thanssdi’s and health-care provision strikes many Americans as more important than pensions — especially for the very poor. There is also less of a perverse-incentive issue involved with ltc. Whereas those who are paid by ssdi to not work will generally be unemployed and remain so, people are very loath to relinquish their independence and therefore won’t use ltc benefits until they absolutely can no longer live on their own.

Nevertheless, the traditionalist principle can still be effectively employed to reduce the middle-class asset spend-down that plagues ltc. Right now, those with the assets to purchase private insurance are discouraged from doing so because of their ability to shift around or spend-down assets and acquire Medicaid eligibility. This discourages traditional virtues and encourages the entitlement mentality every bit as much as other easy-to-access entitlement programs. While it is very important to prevent spousal impoverishment for those married to ltc beneficiaries and maintain decent living standards for those returning from institutionalized care, policies should encourage individuals to use their assets on private plans instead of depleting them to gain Medicaid coverage.

Recent reforms are already drawing on this principle. Provisions in the Deficit Reduction Act (dra) of 2005 set new restrictions on asset transferring and denied Medicaid eligibility for those with certain levels of home equity — over $500,000 (or up to $750,000 in states that have chosen to raise standards above and beyond the federal threshold). It also made the ltc Partnership Program available in every state. Previously only available in four states, the Partnership Program allows Medicaid applicants who purchased private ltc insurance to protect their assets from being counted toward Medicaid eligibility if they have depleted the benefits from their plan. Consumers fear private programs because of the programs’ inability to cover all ltc needs. When benefits are exhausted, policyholders are left to find other sources of care, such as Medicaid. But partnership plans encourage people to purchase private plans because they are precluded from the risk of having to spend down their assets after their benefits are exhausted. States have also implemented the “Own Your Future” Campaign, which “aims to increase consumer awareness about the need to plan for long-term care and provides tools and information to help people plan for their long-term care needs.”20

Ultimately, though, the libertarian principle will take precedence in solving the ltc problem. Conservative ltc policy must rely on private-sector policies to bear the burden, much as the private sector already does for health, life, auto, and homeowners’ policies. Conservative reformers should seek ways to establish pre-funded private accounts, such as those proposed for Social Security, to help people prepare financially for the purchase of ltc policies in their later years.

Pairing ltc insurance policies with private life-insurance policies is another option for stimulating the private market. An effort to couple plans together would not only reduce costs but would also increase the value of ltc insurance as well. Currently, many programs do not cover inflation in health-care costs, or are capped for specified inflation rates, and policies that brace for inflation are much more expensive. With a deeper applicant pool, policies will be better able to cover costs. Plus, with ltc insurance paired with life insurance, insurance companies could better mitigate the problem of adverse selection (i.e., enrolling mostly those who are likely to use lots of benefits) in ltc.

Expanding the market for private ltc insurance will also unleash private-sector innovation. As more people enter the private market, an insurer will have more incentive to ascertain their wants and needs and to craft new insurance products accordingly.

Forgotten no more

It is imperative that conservatives remember the forgotten entitlements and seek to fix their broken parts by applying conservative principles to practical reforms. If the nation is serious about solving its fiscal crisis, these forgotten entitlements must be addressed, and their extension of the entitlement mentality to large numbers of the middle and working classes ended.

1 Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds, “The 2007 Annual Report” (U.S. Department of the Treasury, 2007). Bureau of Economic Analysis, “National Income and Accounts Table.” Social Security Administration, “ssa’s Performance and Accountability Report for Fiscal Year 2006” (2006).

2 Congressional Budget Office, The Long-Term Outlook for Medicare and Medicaid (2007). Kaiser Family Foundation, “Distribution of Medicaid Spending on Long Term Care, fy2006,” see http://www.statehealthfacts.org/comparetable.jsp?ind=180&cat=4&sub=47&yr=29 &typ=4. (accessed January 4, 2009).

3 Executive Office of the President of the United States, Budget of the United States Government Fiscal Year 2007, see http://www.gpoaccess.gov/usbudget/fy07/browse.html (accessed January 4, 2009).

4 David H. Autor and Mark G. Duggan. “The Rise In The Disability Rolls And The Decline In Unemployment,” Quarterly Journal of Economics118 (2003).

5 Kaiser Family Foundation, “Distribution of Medicaid Spending on Long Term Care.”

6 Ellen O’Brien and Risa Elias, Medicaid and Long-Term Care, (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2004).

7 Kaiser Family Foundation, “Distribution of Medicaid Spending on Long Term Care.

8 David H. Autor and Mark G. Duggan. “The Growth in the Social Security Disability Rolls: A Fiscal Crisis Unfolding”, Quarterly Journal of Economics (2006).

9 Social Security Advisory Board, “The Social Security Definition of Disability” (2003), see http://www.ssab.gov/documents/SocialSecurityDefinitionOfDisability.pdf (accessed January 4, 2009).

10 Social Security Advisory Board, “The Social Security Definition of Disability.”

11 Social Security Administration, “Social Security Beneficiary Statistics,” see http://www.ssa.gov/oact/stats/dibenies.html (accessed January 4, 2009).

12 U.S. House of Representatives, Ways and Means Committee, Overview of entitlement programs: 1994 Green Book, see http://aspe.hhs.gov/94gb/sec10.txt (accessed January 4, 2009).

13 Autor and Duggan, “The Growth in the Social Security Disability Rolls.”

14 Judith Kasper, Barbara Lyons, and Molly O’Malley, Long-Term Services and Supports: The Future Role and Challenges for Medicaid(Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2007).

15 Kasper, Lyons, and O’Malley, Long-Term Services and Supports.

16 Kasper, Lyons, and O’Malley, Long-Term Services and Supports.

17 Jeffrey Brown and Amy Finkelstein, “The Interaction of Public and Private Insurance: Medicaid and the Long-Term Care Insurance Market” (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2004).

18 Ari N. Houser, “Long-Term Care” (aarp, October 2007

19 O’Brien and Elias, Medicaid and Long-Term Care.

20 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Long-Term Care Reform Plan (2006).