- History

- Military

The passing of president George Herbert Walker Bush has, inevitably, recalled his role in the most momentous moments of the late 20th century: the fall of the Berlin Wall in the fall of 1989 and the complete collapse of the Soviet empire two years later. That this came about peacefully is still something of a wonder, and is alone more than enough to enshrine our 41st president as a superb statesman.

A more complete history of the first Bush years would include other significant triumphs, most notably the rallying of the Desert Storm coalition in 1990 and the crushing of Saddam Hussein’s “Republican Guard” in the spring of 1991, a lopsided demonstration of American military preeminence foretold in the lightning campaign to oust Manuel Noriega from Panama in 1989. The president was a man for his time, from his heroism as a naval pilot in World War II through his presidency, and he embodied the very best of the tradition of the late-century American establishment.

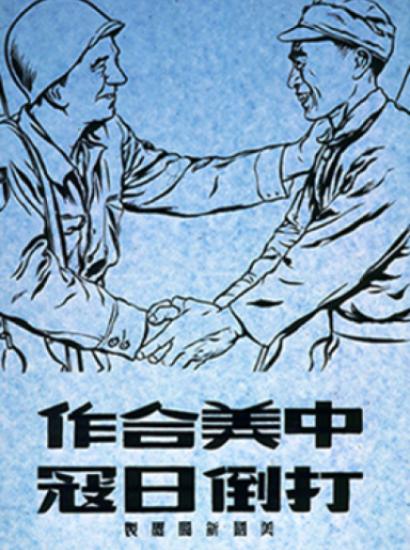

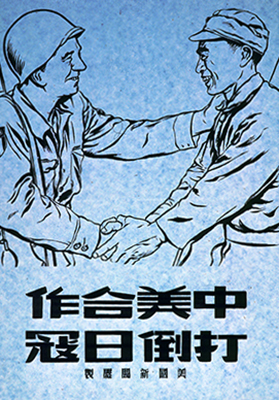

But the story would also include ambiguities that, in retrospect, mute the Bush glow. In particular, the fumbled response to the Tiananmen Square uprising and, in June 1989, the massacre of dozens of democracy demonstrators reveals the limits of the tradition and establishment that positioned “The Relationship” with the Beijing regime at the center of American strategy-making. This questionable judgment is still a powerful one, despite the current administration’s admission that China has become a global great-power competitor.

In his memoir A World Transformed, written with his long-time sidekick and national security adviser Brent Scowcroft, Bush was candid and unapologetic about his handling of the Tiananmen crisis. He recorded in his diary for June 20, more than two weeks after the killing of dozens of demonstrators, that “I’m sending signals to China that we want the relationship to stay intact, but it’s hard when they’re executing people….Dissident Fang [Lizhi, who had sought refuge in the U.S. embassy in Beijing] is making things much worse and Fang’s son showed up at a [Senate Foreign Relations Committee] hearing under the patronage of [North Carolina Republican Sen.] Jesse Helms—stupid—and it just makes things worse.”

Tiananmen came six months before the Wall fell, but even after the break-up of the Soviet Union there was no real reassessment of the strategic partnership with Beijing. The tradition was no longer a guiding light but a set of blinders, and enthusiasm for the economic reforms of Deng Xiaoping swept other concerns aside. Running against Bush in 1992, candidate Bill Clinton excoriated the president for kowtowing to “the butchers of Beijing,” only to usher China into the World Trade Organization on generous terms.

So, if rethinking The Relationship was beyond the ken of President Bush, a proud “China hand” and ambassador to Beijing, it has taken decades and the icon-busting contrariness of Donald Trump to look beyond it. And who can say whether future presidents—or Trump himself—will retreat to the comfy chair of tradition? What Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger have joined, can anyone rend asunder?