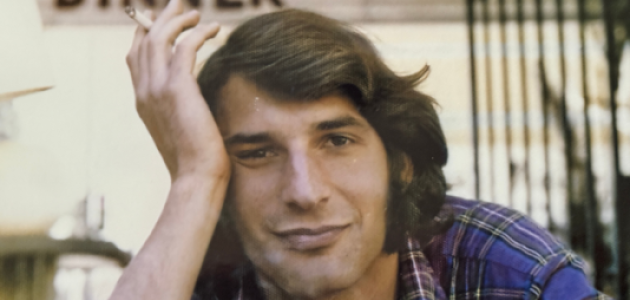

US Navy admiral Cecil Haney, who currently serves as commander of the United States Strategic Command, recently visited the Hoover Institution. In addition to private meetings with the current class of National Security Affairs Fellows and Hoover scholars, Hoover senior fellow Amy Zegart and the National Security Affairs Fellows hosted Admiral Haney for a special breakfast talk and a discussion of US strategic capabilities and deterrence in the twenty-first century.

“We underrate the strategic deterrence mission in spades,” said Admiral Haney, arguing that experts in strategic deterrence were often seen as “Cold War dinosaurs”; in reality, the field has evolved and grown increasingly complex due to changes in technology, expanding frontiers such as cyberspace and outer space, and emerging threats around the world. Strategic deterrence, according to Admiral Haney, is all about information, such as moving it and misinformation, and imagining various threats and responses to prepare ourselves for the future, in line with American democratic values but remembering that our adversaries might not operate under the same code of conduct. “How do we challenge our thinking in order to have the upper hand in managing strategic stability?” Admiral Haney asked. “This business of having a deeper understanding of our adversaries and potential adversaries . . . provides our national security apparatus, our president, etc. the decision space in which to confront these things that are key and essential to our future.”

During the discussion, Admiral Haney warned about overly emphasizing the promises of new technologies. In particular, technology can often change faster than its security, an important factor for our nation’s most sensitive information. He also discussed the US debt and budget at length, declaring that “the biggest enemy to the United States is our approach to sequestration,” characterizing it as a “meat-cleaver approach” and a “force to be reckoned with.” He ended with a warning on characterizing the United States as “weak- kneed,” arguing that there are other ways to be powerful besides military force and that “we have to be mindful of potential consequences of our activities.”