Historian Margaret MacMillan observed that “we can learn from history, but we can also deceive ourselves when we selectively take evidence from the past to justify what we have already made up our minds to do.” Government regulators who use the lessons of history in to solve today’s public policy problems may, in fact, fall into such a trap. The Hoover Institution Working Group on Intellectual Property, Innovation, and Prosperity (Hoover IP²) aims to help ameliorate this problem with its latest project: a book that examines the economic and legal history of patents and patent systems.

Hoover IP² director Stephen Haber and Naomi Lamoreaux of Yale University are co-editing the volume. “The premise is that there are lots of stories about patents and inventions that have been used to make cases for or against the value of patents,” explains Haber, “but these stories are not strongly moored to the facts. This nine-chapter volume is meant to get the history right.”

The contributors hail from a variety of academic disciplines and include economic historians, legal scholars, political scientists, and economists. Contributors include

- Jonathan Barnett, Gould School of Law, University of Southern California

- Christopher Beauchamp, Brooklyn Law School

- Sean Bottomley, Max Planck Institute for European Legal History (Germany)

- Gerardo Con Diaz, Department of Science and Technology Studies, University of California, Davis

- Alexander Galetovic, Department of Economics, Universidad de los Andes (Chile)

- Stephen Haber, Hoover Institution and Department of Political Science, Stanford University

- John Howells, Department of Management, Aarhus University (Denmark)

- Ron D. Katznelson, Bi-Level Technologies

- Zorina Khan, Department of Economics, Bowdoin College

- Naomi Lamoreaux, Department of History, Yale University

- Victor Menaldo, Department of Political Science, University of Washington

- Steve Usselman, School of History and Sociology, Georgia Institute of Technology

The contributors take on historical questions that speak to current debates about the US patent system. Khan examines past national innovation systems to find which models have yielded the greatest development and diffusion of technology, while Menaldo uses the case of Spain to assess the benefits for developing countries of implementing strong protections for intellectual property rights. Bottomley and Howells and Katznelson revisit the literature that asserts that patents held up innovation or the commercialization of innovation.

Usselman documents the important role played by federal judges in California in supporting the growth of an innovative regional economy in the early twentieth century. Beauchamp’s painstaking research on historical trends in patent litigation forces us to revise our understanding of current trends in the scope and levels of such litigation. Barnett shows how federal antitrust policy reshaped the operation of the patent system in the mid-twentieth century.

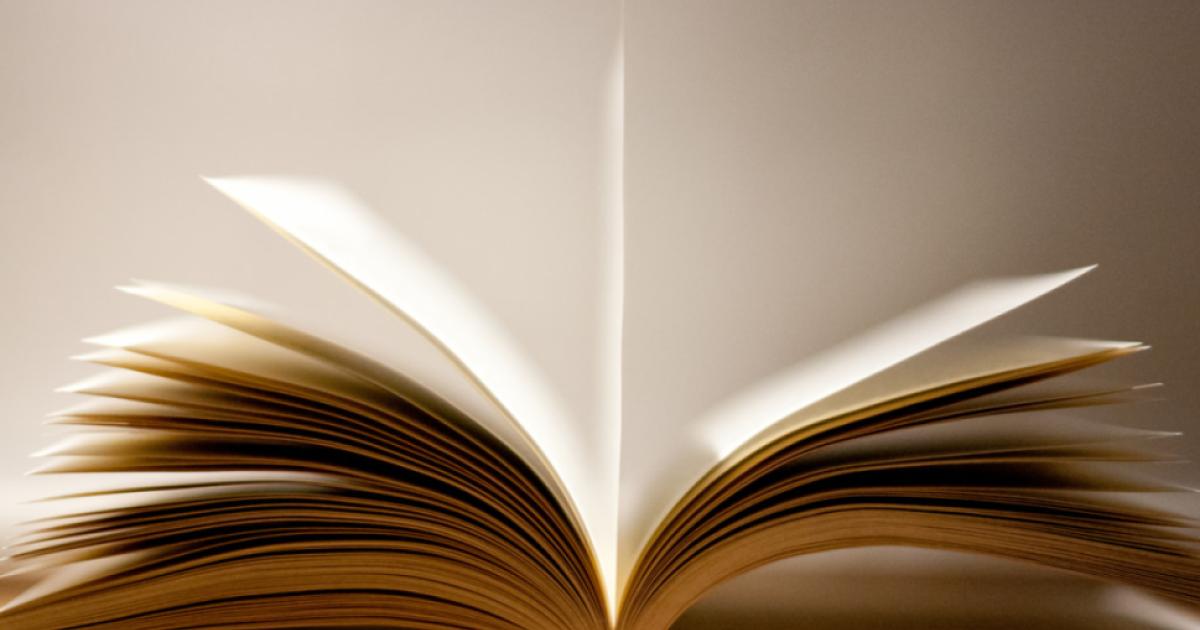

Galetovic highlights the importance of intellectual property in patents for decentralized patterns of innovation in semiconductors. Finally, Con Diaz revises the history of software patenting, showing that the Patent Office’s decision to allow such patents was not a radical break with past practice but the incremental extension of earlier efforts by hardware manufacturers to protect particular ways of programming their machines.

The contributors will present the chapters at the Hoover IP² May 2018 conference, “What Patents Really Do: Historical Perspectives on Current Debates.” For more information or to RSVP, click here.

The conference is the tenth in a series of semiannual conferences organized by Hoover IP². The conferences feature presentations of leading academic research addressing intellectual property rights, particularly how intellectual property rights affect innovation. Papers presented at the Hoover IP² conferences emphasize reason, data, and evidence over rhetoric and ideology.