By Jonathan Movroydis

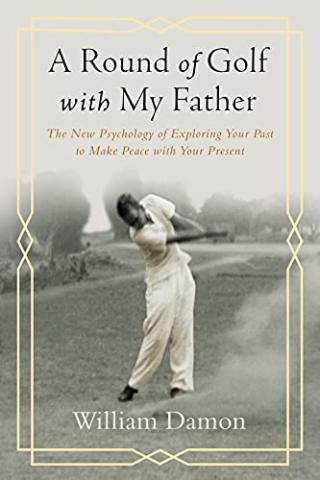

In this interview, William Damon, professor of education at Stanford University, director of Stanford’s Center for Adolescence, and senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, discusses his new book, A Round of Golf with My Father: The New Psychology of Exploring Your Past to Make Peace with Your Present.

Damon’s research explores how people develop purpose in their work and personal lives. Part memoir and part study of life-span human development, the book tells how Damon learned the true story of the father who abandoned him as a child and how he sought to find meaning and redemptive life lessons from his discoveries. Damon demonstrates how he applied on himself a “life review,” a narrative identity approach developed by renowned psychiatrist Robert Butler. With a life review, individuals can forge positive ways of thinking about the challenges of their past lives in order to achieve hopeful and purposeful futures.

Why did you write this book?

I had mixed motives. I had a professional interest in exploring a psychological approach called “life review.” It is a way of thinking about your past that's systematic and intentional and prepares you for a forward-looking future. My research at Stanford has been focused on future mindedness, goal-setting, and especially the concept of purpose. What I had not explored in my prior work was how thinking systematically about the past can contribute to these future-oriented psychological strengths.

I also had a dramatic personal interest that captured my imagination, which is that relatively late in my life, I made an enormous, surprising discovery about my own past having to do with my father who was missing from my life right from the very beginning. This discovery was introduced to me by my daughter, interestingly enough.

How does the “life review” approach work?

Everybody thinks about their past all the time. This happens quite naturally. We all tell stories about our past. Sometimes little anecdotes. Sometimes about our immediate past. We went shopping yesterday, or we went on a trip to Yosemite over the weekend, or last week we had a visit with our families. We're always telling stories about things that happened to us, but we do it in a fairly haphazard way. We can be nostalgic. We can recognize the mistakes we have made and try to figure out how to deal with them. It’s always a mixed bag of memories and images that we have. It’s natural.

I discovered a method that had been developed by a very accomplished psychiatrist, Robert Butler. Early in his career, before he became a public figure, Butler was the first director of the National Institute on Aging. He wrote a Pulitzer Prize-winning book on aging called Why Survive? Being Old in America. Early in his career, before he started writing popular nonfiction, Butler developed the “life review” approach. He dealt especially with depressed patients. Butler believed that if he could encourage the people to systematically think about memories in their past that had given them a lot of fulfillment, despite their regrets, they could help themselves better attain future purpose and build a healthier life.

I am not a clinician or a psychiatrist, but I became very interested in “life review” in relation to my own work on how people can develop purpose in life. After my late-life discovery about my missing father, I decided to try the life review approach on myself. I had a particular incentive to do this because what I discovered about my own past changed my understanding of how I came to be the person I am now. I needed to learn more about my past and the choices that I and others had made that influenced my development. This was actually important for me to both affirm my present and prepare for positive future choices.

Can you tell us about the process of applying the life review approach on yourself?

I will summarize the personal events that led me to my life review. That will, I think, help me explain what I did and why I did it. Shortly after I turned sixty, I received a call one night from my daughter, who was then in her thirties. She is an economist who travels extensively for her work and is a prodigious researcher in her own right. At the time, she was traveling in Cape Town, South Africa, and experiencing jet lag. During that sleepless night, she went online to find everything she could about her grandfather (my father), whom I had never met.

My father served in the US Army in Germany during World War II, and all I ever heard about him when I was a child was that he went missing during the war. Later, when I was in college, I was told that he actually survived. The truth be told, he actually abandoned my mother and me. I didn't want to identify with him. I didn't want to meet him. I didn’t want to know more about him. I had never even seen a picture of him. However, after her web search, my daughter called me and said, "Dad, I don't know if I should tell you this, but I found out something about your father."

I discovered that, among other things, my father had a very significant career. He also married for a second time and had other children who were my half-sisters, whom I later became interested in meeting. Most importantly, my father had accomplished feats in his life that actually had influenced my own life in ways that I never understood. We attended the same primary school and the same college. I had no idea that my father’s education determined my mother’s choice of where I would attend school. Suddenly, the reasons behind many of my choices and experiences throughout life started to make more sense.

In adopting Butler's method of life review, I began with activities such as returning to my high school and obtaining records of my father who attended there twenty years prior. My father and I even shared some of the same teachers, who wrote reports about both of us as students. These teachers had never told me about this connection with my father. My mother probably had convinced them to maintain the bubble of ignorance that I was living in. I also conducted research on his history in the army and discovered some amazing aspects about his career. I interviewed still-living friends of his and relatives of mine. My mother had already passed away at the time, but I revived some of my memories of conversations I'd had with her.

This was an extensive research project. Through interviews and the discovery of public documents, I was able to weave together a story about my father’s life. In the process, I was able to establish a clearer understanding about my qualities and what had brought me to my present life situation. It also taught me how I could improve myself and cope with my regrets and resentments stemming from my father abandoning my mother and me at an early age. Ultimately, I was able to forgive my father, which alleviated my own feelings of resentment and regret.

How did you discover qualities in yourself that you didn’t understand otherwise, especially those that you shared with your father?

One way was as simple and direct as uncovering school records, from my elementary grades through college, including comments that my teachers wrote about me. I'll give you one small example: from high school through college, many of my teachers and counselors wrote that I could be stubborn. One of my high school guidance counselors wrote, “Bill considers himself liberal and open-minded. But when he forms an opinion about an issue, he just bores into it. He doesn’t really consider other people’s points of view.” Later, in college, it was recorded that I engaged in arguments with academic advisors about my research methods. Maybe it's not too late for me to learn humility. There are also some characteristics that I share with my father that I had never recognized. He was always seen as very gregarious. That was a comment that has been made about me as well.

The reason why I titled the book A Round of Golf with My Father is that, when my daughter uncovered the truth about my father, I was surprised to find out that he was a very skilled golfer. I love golf myself, but I'm very far from a great player. I grew up in somewhat disadvantaged circumstances. My father didn’t support us financially after he left. I never could afford golf lessons. This sounds like a minor problem, but it was actually a source of my resentment. Why didn't my father ever show up? Why didn't he teach me how to play golf?

My perspective on my father’s golf game was symbolic of a whole range of feelings. I actually discovered an old scorecard from my father’s golf bag that one of my new relatives had sent me. I went to his old golf club and played nine holes, pretending that he was with me. So it was an imaginary round of golf, but a meaningful one for me. I actually played against his scorecard, but I ultimately could not match him. It was kind of a psychological exercise in redemption and reconciliation, and it gave me a sense of connection with my father that I never had.

You had mentioned that your father lived a remarkable life. What was your reaction upon learning about all of his accomplishments?

After serving in the army during World War II, my father joined the US War Department and helped with the de-Nazification of Germany. He was put in charge of some small towns and helped advance their transition to democracy. He then went on to have a significant diplomatic career in Southeast Asia. During his service in Thailand, for example, he and his second wife became friendly with the country’s king and queen. Notably, he helped establish a group of cultural centers called “America House” that promoted democratic values, first in Germany and then later in Thailand.

At the end of his army career, he was called on to testify at a high-profile war crimes trial. At that time, a lot of people refused to testify because there were so many threats. I uncovered all the records of this trial and his testimony.

I admired his moral courage. It was a positive experience for me to find out that he actually had a distinguished career on the side of liberty and democracy and in truth-telling and justice. This did not cancel out by any means the irresponsible manner in which he abandoned my mother and me. He hurt my mother very badly. But the nature of his career helped me understand his motives for not coming back to the States.

I eventually took the important step of forgiving my father. When you forgive someone, eventually it's not so much that you're doing them a favor, you're doing yourself a favor because you're relieving yourself of a lot of resentment and anger that are not psychologically in your own best interest.

What do you hope readers gain from this book, especially those people who are trying to come to grips with their past?

My first hope is that readers will find it an interesting story. It is a story with a certain amount of drama and human interest. It's a unique story, but it's not actually unique in all regards. Many of my friends and colleagues who read the book told me about undisclosed family mysteries, about early unresolved mistakes they made, as well as their resentments and parts of their past that they want to better understand. I am hoping the book will help people, through my example, understand their past more clearly so that they can make peace with their present and prepare for a purposeful and hopeful future. That's what my life review accomplished for me.