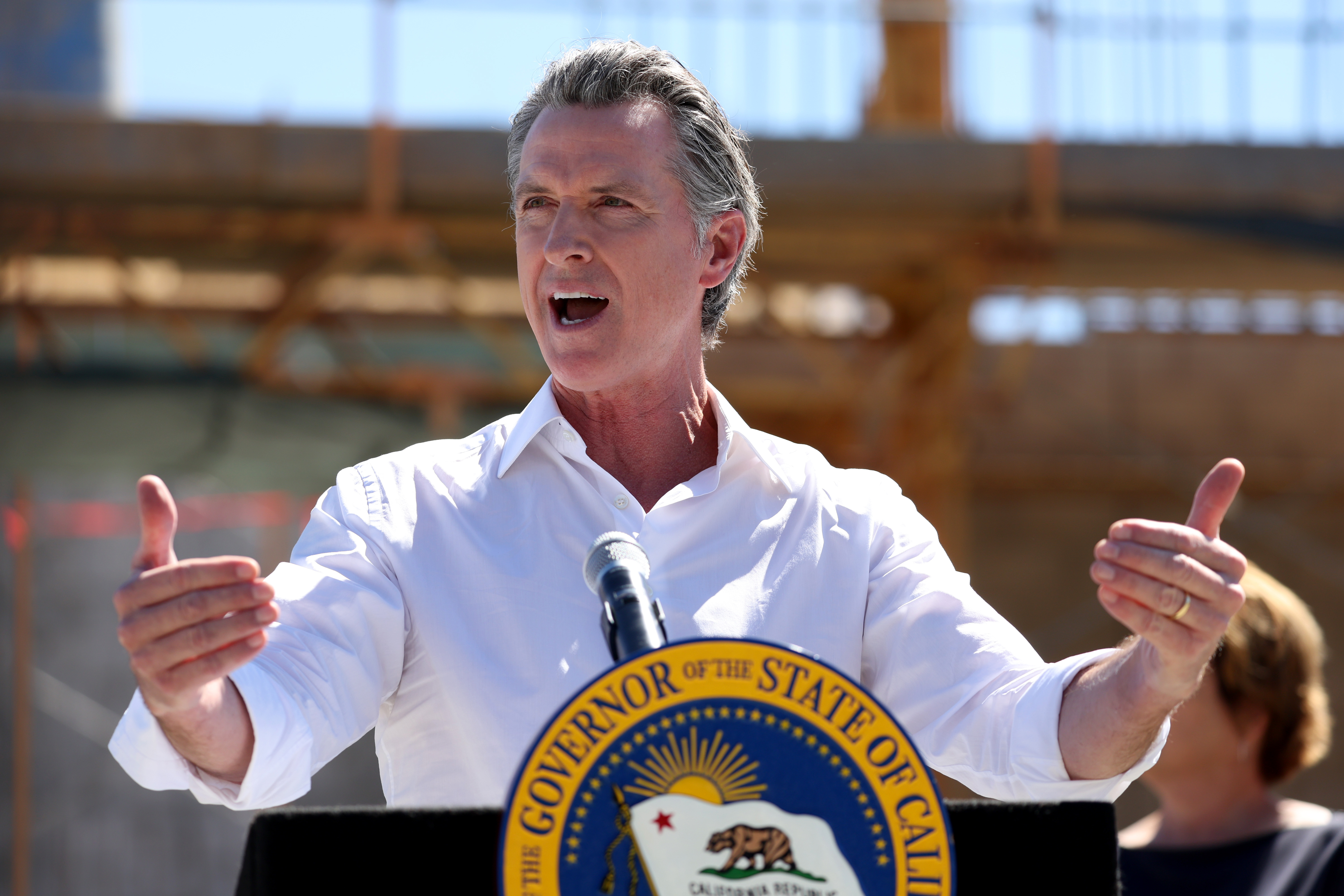

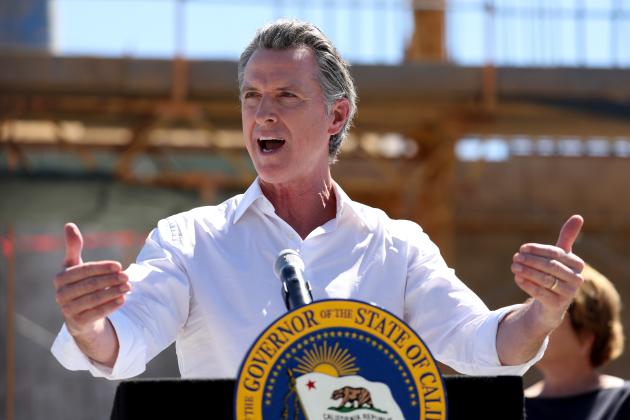

In a news account that sounded more like high school drama than it did the high ground of higher office, we’ve been informed that California governor Gavin Newsom reportedly was left “seething” after President Biden weighed in on a piece of legislation currently awaiting the governor’s signature or veto.

The matter in question: AB 2183, which would make mail-in voting available to farmworkers participating in union elections. Supporters of the bill claim it would give farmworkers the same voting luxury enjoyed by all Californians in statewide elections; critics argue that it would give unions unrestrained access to ballots, potentially opening the door to election fraud.

Where the American president and the California governor part ways: the former is calling on the latter to sign the bill into law, despite the latter’s objections to said measure (also playing a role in this drama: labor exerting all kinds of pressure on the governor to get the outcome it desires).

At this point, you might ask: why the drama between two prominent and labor-friendly Democrats? After all, it’s not like Newsom misses many chances to do favors for California’s unions, who rarely miss a chance to bankroll him in his times of need. This is the same governor who, on Labor Day, signed a measure giving organized labor considerable sway over the California fast-food industry’s wages and working conditions (on an unhappy note, a “Happy Meal” in the Golden State, in the near future, may end up costing an extra 20%).

That said, AB 2183 is a departure from the California norm in that Newsom cares not for the bill in its present form and his office has signaled that he intends to veto it—if so, repeating what happened last October, when the governor rejected a similar measure (AB 616) that would have made it easier for California farmworkers to vote by mail in union elections.

Newsom’s concern: election integrity. How odd. This is the same governor who doesn’t have a problem with the controversial practice of “ballot harvesting” (allowing third parties to collect and deliver ballots to drop-off locations). Nor has Newsom signaled any concern with an election system in which the numbers don’t always add up (in Los Angeles County, there are more registered voters than there are voting-age residents) or ballots that take weeks—not hours or a few days—to fully count (hence the term “Election Month”).

But in this case, in the aftermath of Biden coming out in favor of AB 2183, what Newsom is demonstrating is political thin skin. (“Farmworkers worked tirelessly and at great personal risk to keep food on America’s tables during the pandemic,” Biden said in a statement earlier this month. “In the state with the largest population of farmworkers, the least we owe them is an easier path to make a free and fair choice to organize a union. I am grateful to California’s elected officials and union leaders for leading the way.”)

Another way to phrase that: the governor can dish it out better than he can take it.

Keep in mind: it was only four months ago that Newsom, with all that he sees wrong in red states (this would include abortion, voting rights, and what’s read in classrooms), went on the following rant outside a Planned Parenthood office in Los Angeles: “Where the hell is my party? Where’s the Democratic Party? . . . Why aren’t we standing up more firmly, more resolutely? Why aren’t we calling this out? This is a concerted, coordinated effort. And, yes, they’re winning. They are. They have been. Let’s acknowledge that. We need to stand up. Where’s the counteroffensive?”

One way to interpret that mini-tirade: Newsom was trying to rally the Democratic faithful.

A more cynical read: it was a shot across the bow of a struggling Democratic president who may be a one-term act due in no small part to his party’s desire to pass the torch to a more youthful Democrat (if that’s the case, cue the Newsom 2024 speculation).

During the summer, Newsom’s rising national profile didn’t go unnoticed by the White House—Biden’s advisors are reportedly “irked” by Newsom generating 2024 buzz as he trolls Republican governors via his social media accounts. But the question is: Who should be more irked, the president . . . or the vice president?

It’s not a rarity for two individuals from the same state, belonging to the same political party, to compete as presidential hopefuls in the same primary cycle. The 2016 Republican field, for example, included fellow Floridians Jeb Bush and Marco Rubio, as well as fellow New Yorkers Donald Trump and George Pataki and fellow Texans Ted Cruz and Rick Perry.

But Newsom and Vice President Kamala Harris are unusual in that their political careers have been on parallel tracks—both serving as San Francisco elected officials (he was mayor, she was district attorney) before pivoting to statewide office in 2010 (Newsom elected lieutenant governor, Harris state attorney general), then advancing one or more rungs up the political ladder (Harris elected to the US Senate in 2016, then the vice presidency; Newsom elected in governor in 2018 and pretty much a shoo-in for reelection this fall).

However, the presidency puts the parallel Democrats on a collision course, assuming Biden chooses not to run, Harris opts to succeed him, and Newsom likewise enters the Democratic field as the obligatory outsider offering up his state as an ideal for the nation to emulate.

Is Harris irked by Newsom’s emergence as a national player? The White House isn’t saying.

But it’s worth noting that the vice president is channeling California’s governor in this regard: she’s out on the campaign talking up abortion rights, putting down Florida governor Ron DeSantis and Texas governor Greg Abbott (both preferred Newsom targets), and telling Democrats to vote and trying to pump up her party’s base.

So perhaps Newsom can take some consolation in knowing that at least one prominent Democrat heard what he had to say back in May, during his Planned Parenthood appearance.

But as for the governor fuming over the meddling president, a little intra-California perspective might help. Newsom governs not so much a state as the equivalent of a nation in its population, economic clout, and human and topographical diversity. It’s also a land that doesn’t pay as close attention as it should to policy matters in Sacramento —not unless the state’s actions have a very personal impact (schools closed amidst a pandemic; the state’s power grid buckling in a heat wave).

While the governor may be peeved by the president interjecting himself into Sacramento’s legislative process, it comes at a time when Californians arguably had other matters on their minds (the aforementioned heat wave, a new school year, the chances of an epic commercial real-estate crash in this new age of remote work—or, just the other day, the weirdness of howling winds and flash floods as the remnants of a tropical storm drifted into Southern California).

What this means for Newsom: better to move on from what the president had to say with regard to the plight of farmworkers, understanding that unsolicited political advice is a two-way street.

And for Vice President Harris: keep an eye on the governor on the parallel track. He may be on a collision course with you—to use an old Newsom phrase, “whether you like it or not.”