- Military

- Revitalizing History

“Should the United States prioritize saving severely wounded service members on the battlefield in a future great power conflict, even if doing so diverts combat resources and risks strategic failure?” That is an impossible question to answer, similar to Philippa Foot's Trolley Problem. This philosophical question explores the concept of double effect, wherein she concludes that negative duties (moral obligations not to harm/injure) carry more weight than positive duties (moral obligation to aid/benefit others).

This quandary arises widely, from autonomous vehicle programming to organ transplantation, and appears in popular culture, such as Star Trek’s Spock and Kirk’s dialogue on the Vulcan phrase, “Logic clearly dictates that the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few,” followed by the addition, “Or the one.” Philosophers and writers continue to explore the limits of Utilitarianism, which prioritizes maximizing net benefits. The challenge of battlefield medicine lies in balancing moral obligations to service members with operational and strategic requirements. The answer we choose reflects how we see ourselves as a culture.

The question does not have a singular medical answer; instead, it must balance state-of-the-art trauma care to resuscitate, transport, and treat casualties with troop morale, tactical, and strategic objectives, as well as logistics and materiel resources. The crux of the question rests on two conflicting values—limitations of resources and the importance of the strategic objective. Our culture has decided that some objectives are worth dying for: numerous stories, citations, and medals honor heroes who gave all to win the day.

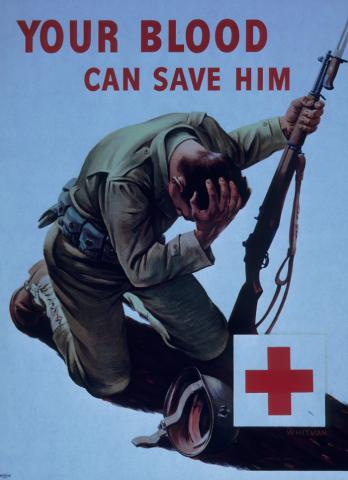

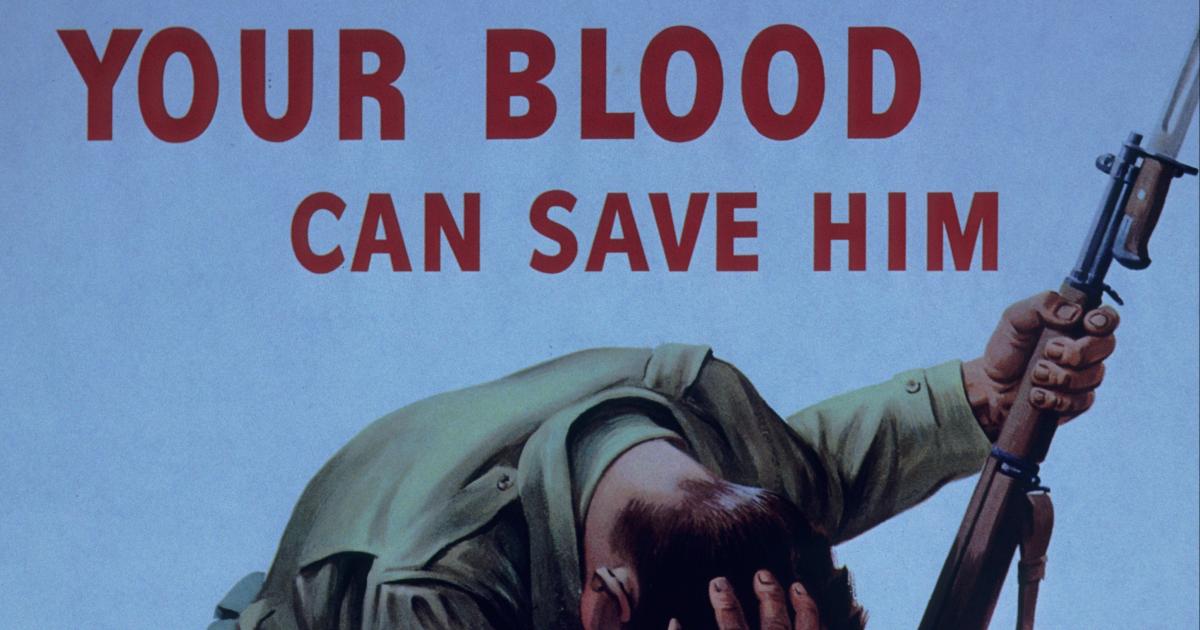

That said, we still prefer to win with the fewest possible casualties, and casualty care often requires high risk and high expense. Abandoning wounded fighters would degrade operational effectiveness by losing trained and experienced personnel requiring ongoing replacements. Importantly, not prioritizing care violates the implicit social contract between the enlisted and the U.S. military. Our citizens and our all-volunteer force believe that the government will care for them and have high expectations for that care. Abandoning the wounded would erode public and Warfighters’ trust in the military and damage morale, social cohesion, recruitment, and retention. The choice not to deliver this care risks serious moral injury, especially for medical personnel whose core moral belief is the drive to provide care.

Tangible examples of this are evident in the numerous medals awarded to both living and deceased medics for prioritizing the safety of their wounded comrades over their own. Battlefield medical care is critical to unit morale and cohesion. Knowing that the military will do everything to save them or their buddy has a profound effect on the unit and individual soldiers’ confidence to engage the enemy.

Balancing these resources is not a new concept; it has evolved alongside warfare. Napoleon’s Battalion Surgeons were early pioneers in casualty care. We have many more options today, but they also require more resources and necessitate ongoing adaptation. The use of combat drones has already changed injuries as well as casualty transport needs. Forward thinkers have brought genuine innovations and stimulated the rediscovery of older techniques.

For example, a bold vision of future battlefield surgery drove the development of robotic surgical platforms, now standard tools in hospitals. Tourniquet use represents a rediscovered technology that was abandoned after World War II and became a standard lifesaving intervention in both military and civilian medicine, and once again is undergoing evaluation and updates following improper use in recent world conflicts. Another key innovation was both real-time and retrospective evaluation of casualty care. The Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) guidelines were initially developed for special forces deployments in the 1990s to address extremity hemorrhage, the leading cause of preventable death, and subsequently became standard for all deployed service members with demonstrable results. TCCC divides care into phases: “care under fire,” “tactical field care,” and “casualty evacuation care,” with each phase balancing medical urgency against the safety of both casualties and rescuers.

The development in 2004 of the Joint Trauma System remains a key driver in the ongoing evolution of military medicine through practice guidelines, education programs, and trauma registry analyses. These programs actively address the critical need to maintain multidisciplinary surgical team readiness during the current interwar period with few war-wounded casualties. Significant challenges exist today. Injuries received downrange bear little resemblance to civilian trauma injuries, and surgical sub-specialization and procedure innovation have moved surgery away from experienced “generalists,” and from maximally invasive open to minimally invasive operative techniques. The driving question is how surgical teams can acquire and maintain critical skills to treat complex injuries.

There will always be the need to make triage and tactical decisions, but relegating severely injured patients to no treatment will have serious consequences. Strategically, it is the will of our citizens that empowers our military to prevail. That “will” would be endangered if they thought their injured sons and daughters were not being sufficiently cared for. Therefore, the U.S. Military must continue to extend significant resources to battlefield medicine. Continuous transformation of the system is crucial for maximizing the impact of battlefield medical care and minimizing the strategic operational implications.

Sherry M. Wren, MD, FACS, FCS (ECSA), FISS, is Professor of Surgery and Director of Global Surgery at the Center for Innovation in Global Health, Stanford University, and Director of Clinical Surgery/Chief of General Surgery at the Palo Alto Veterans Health Care System. She serves as Secretary of the American College of Surgeons, Professor Extraordinary at the Centre for Global Surgery, Stellenbosch University, Adjunct Professor at the Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, and former Honorary Professor at the Centre for Trauma, Queen Mary University of London. She has leadership roles across numerous national and international organizations and the recipient of the 2017 ACS International Surgical Volunteerism Award.

Dr. Wren is Editor-in-Chief of the World Journal of Surgery and has served on the editorial boards of JAMA Surgery, Surgical Endoscopy, Journal of Laparoendoscopic and Advanced Surgical Techniques, and the East and Central African Journal of Surgery. Her clinical/research interests include global surgery, surgical systems/technology, robotics, humanitarian surgery, trauma, and GI cancers. Clinically, her focus is HPB/gastrointestinal malignancy, surgical robotics, and conflict care. She has worked extensively as a surgeon with Médecins Sans Frontières in conflict zones.