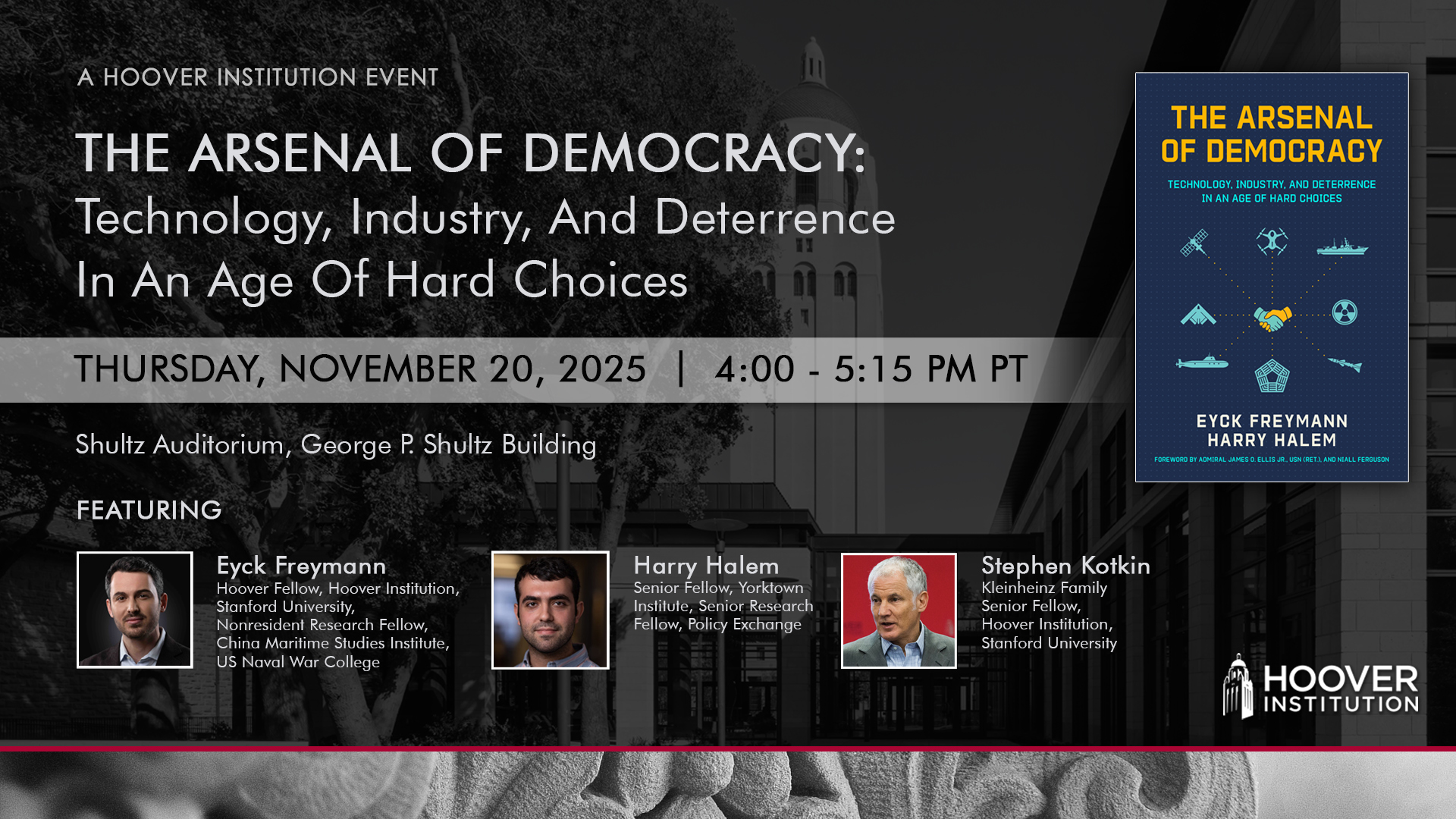

The Hoover History Lab and its Applied History Working Group in close partnership with the Global Policy and Strategy Initiative held The Arsenal of Democracy Technology, Industry, and Deterrence in an Age of Hard Choices on Thursday, November 20, 2025, from 4:00 PM - 5:15 PM PT.

The event featured the authors Eyck Freymann, Hoover Fellow, and Harry Halem, Senior Fellow at Yorktown Institute, in conversation with Stephen Kotkin, Kleinheinz Family Senior Fellow.

- Hello everybody and welcome. I'm Steven Kotkin, a senior fellow here at the Hoover Institution and the director of the Hoover History Lab. And in cooperation with the GPS program, global Policy Studies, Jim Ellis, Admiral Jim Ellis and David Federer, and also with the applied history working group, Neil Ferguson. Neither Admiral Jim nor Neil could be here today in any case, in combination with them. The Hoover History Lab is thrilled to present another really important book talk. One of the goals of the Hoover History Lab is investment in human capital. And we take particular pride in giving platforms to young people who have a lot to say on really critical policy issues. History Lab is the application of consequential history to contemporary policy challenges, but it's also young people who do this and we incorporate into our work with the greatest pride and and also with the greatest benefit. Ike Freeman is a Hoover Fellow here, multi-year assistant professor equivalent. This is not his first book. He's got another book that predates this in more coming. He also wrote a really important policy intervention on the economic security commons one the day after a Taiwan contingency, which really important intervention. And this arsenal of democracy today is a continuum, a part of that type of really important work. Harry Haem comes to us from the Yorktown Institute in Policy Exchange. And another really good thing about Ike's work is that he does it almost always in collaboration. The day after Taiwan scenarios was with Hugo Bromley, and today we have Harry Hale and we like to see that type of collaboration where the sum is greater than the parts. We're gonna do this as a conversation rather than a a formal presentation. And I'll start the ball rolling with a few questions and then we'll invite members of our live studio audiences we like to call it to, to also post some questions or make some comments. We have a lot of expertise here today in the room and we want to take advantage of that. So let me start out with the first question, which is give us a little insight into the impulse behind the book. What motivated you to take this project on? What sort of question were you aiming to potentially provide an answer for intervention? And what particular policy debate? How did this come about this book?

- Well, thank you Steven for stepping in and for hosting this today. Thank you all for being here, and thank you for outing me as the person on this stage who wrote a book about a subject. I don't know particularly much about the origin of this project about five years ago.

- I don't think I did that, but I'm, I'm listening.

- The origin of this project about five years ago was that I, as a student of China and US-China strategic competition began to get the sense that the military balance was shifting rapidly in the Taiwan Strait. And that I didn't have a handle on what the key determinants of it were and how close it was to tipping forever in China's favor.

- Hmm.

- And so I asked Harry, a friend, a naval historian, an encyclopedia of all things military to recommend the book that I should read to get a handle on what a US-China war would be like, what it would take to win, what systems, what capabilities, and then which of those things we have and can deploy and which ones we would struggle to deploy. And Harry said, well, there's no book, but I can send you about 50 people to follow on Twitter and a thousand articles from War on the Rocks.

- Okay, a lot of homework.

- And I was deluged in acronyms and I couldn't put the pieces together. And this began a collaboration that has continued over the past five years as we have tried to put those pieces together and provide answers to those three questions, which are clear and simple enough that regular people can understand them without acronyms. And I think in the process of doing this project, we've realized that in our national security enterprise, we have a lot of specialists who are very good at 1% of the problem or less, but relatively few people who are forced to take a look at the whole system to really grapple with the macro trends and the trade-offs that are involved in making specific choices.

- Okay. So the lack of something to get you up to speed is why you needed to get up to speed yourselves. I take that Harry, and admittedly,

- The majority of the literature that Ike was directed to back in 20 21, 22 is in the footnotes of the book. He did read it. I come at this as the military part of our duo. I'm a naval and military historian by background. I work on operational questions in Europe and the Middle East. I have another book on naval issues. And this matters in particular because for me, this project was as much about explanation as it was about research and learning. The military profession, which includes uniformed officers, but many who don't wear uniforms, many who don't serve historians, intelligence analysts, policy makers, academics, is very bad at explaining to others who work on questions of strategy, Why we matter, why military deterrence matters, particularly against an adversary like China that is so big. And that presents so many different problems. So in the end, we wrote this book to say, the deterrence problem we face in the 2020s and 2030s involves diplomatic elements, economic elements, technological elements. All those have to be gotten right. And my co-author has done fantastic work on other sections of that problem. But without military deterrence as the foundation, nothing else matters and we cannot preserve our interests. Articulating that point takes a full book, and Ike and I have fortunately made a start at writing what we hope is a good one.

- Your readers will definitely weigh in on that. So let's talk a little bit about what you discovered in the process of deciding you needed to write the book and then doing the work and executing the book. What are some of the key points that you would like to convey? Obviously you can't convey them all and people will have to read the book in order to get them all. But give us a kind of appetizer as it were for some of the things that you learned that are really important for us to know.

- So I'll go first. I think the first and most important point is that all is not lost. It was tempting for me as an amateur coming to this problem to see, well, China has more ships, they've got more aircraft, they've got more missiles, they've got more men, they've got more drones, they've got more factories, they've got more ports, they've got more airfields. How could we possibly, how could we possibly win?

- Yeah.

- If, God forbid, we had, good question. One of these confrontations, and what I discovered, which is something that is well known within the profession but not particularly well known outside, is that actually those quantitative advantages, yes, at some point they matter. But the connective tissue that makes a military operate, which is the command and control, the intelligence, the surveillance, the reconnaissance, the ability to communicate across vast distances, to organize a force to have doctrine that delivers resources and capabilities in the right places at the right time. The logistics chains, which are the sinews of the system, these things matter just as much if not more. And also in particular, you can overlearn the lessons of Ukraine. 'cause Ukraine is a land war and a, and naval wars in history just work differently. They tend to be less attritional. They tend to be more characterized by a single high stakes, high intensity engagement Where the side that strikes effectively first enjoys compounding advantages. And there's a number of reasons why that is. They're spelled out in the chapter one on the framework. But this, this finding that the United States actually has advantages in command and control, which also reflect the fact that we trust our own officers and can therefore push decision making power down the chain, gives us significant advantages in the critical early hours and days of a conflict. And therefore, if we can continue to push on those advantages, all is not lost. The second is that China has absolutely enormous quantitative advantages in some of the less prominent parts of the system. It's not just ship building, even though they have over 200 times the shipbuilding capacity that we have. It's that they have economies of scale in the componentry that goes into a lot of these systems, particularly drones that makes us and the rest of the world very reliant upon them. And this is potentially a huge problem if we need to scale production ourselves in a crisis or if they weaponize these interdependencies. And then the third is that allies matter. They matter a lot. And in this political moment, there's a temptation to call allies feckless, and in some ways they have been or free riders because in some sense they are. But allies have capabilities, they have industrial knowledge and process knowledge. In some cases they have geographic advantages that we obviously can't match. They have natural resources without closer cooperation with our allies, we have no chance of solving these significant industrial challenges that we face in time to compete with China in the 2030s when despite our technological advantages, which will probably endure, China will have such massive quantitative advantages that we do run the risk of falling behind.

- Harry, you want to answer that please.

- We're in California, we're approximate to the valley. We're in the heart of American. And in many ways global technology. The difference of course between the tech industry and the round and military questions is no individual app has ever won a war. No individual capability has ever provided such a decisive advantage as to win a military conflict, particularly between great powers

- On the conventional level.

- Instead, deterrence is a system and it's a system that includes nuclear weapons, conventional forces on the surface, in the air, under sea, in space, manned and unmanned systems, different kinds of missiles, cyber capabilities, command and control, which as Ike just put, it, integrates all of these elements together into a comprehensive effective combat system. Deterrence is a system, it can be decomposed into parts as we do in our book, but in the end, we need to reconstruct that system in our minds because that's exactly how the Chinese are thinking about the problem. We need to think synthetically and realize that it's not about one specific set of capabilities, one specific technology. It's about putting them all together, getting alignment across our bureaucracies, military and non-military between us and our allies to drive forward a series of capability developments that in the round can deter and if necessary win an enormous potentially catastrophic war with communist China.

- Let's open up the history box here a little bit further on these issues. So if you look at 1939 to 41, and especially 1941 to 43, the arsenal of democracy theme. You see a United States that is not prepared a for war, a tiny army, no significant military industrial complex in 39, growing slowly, well quickly in some people's minds, but too slowly for what's happen about to happen in 41. And so the war happens and the United States is not really a war economy, a war society, a significant military by 40 and 1941 doesn't go that well, 1942 goes even worse for the US and its allies. 1943 is a different story. And 1944 is domination, right? So it's short period of time where you, you, you go from way behind to way ahead in quantitative terms and in qualitative terms and in organizational capacity. So the reason that was possible is because there was a lot of latent military production capacity in the US civilian economy. So you had these gigantic automobile factories that could produce other things other than automobiles. When so tasked, you had skilled workers across multiple industries who knew how to weld or knew how to do something which was applicable not just in their current tasks but in other tasks. So you had inbuilt potential across many different domains that could be and was mobilized. It wasn't automatic. It took quite a lot of organizational skill and vision. It took people from the private sector being in charge. So we shouldn't just assume that if there's latent capacity, it, it's gonna all come online soon enough when, when the crisis hits. But how do we find that equivalent? Or we do, we find that equivalent. Now if we're talking about a revival of an arsenal democracy, and we're looking at assembly lines, productive capacity, skilled labor, operation of government, private sector interface, some of these variables that I'm talking about from 39 to 41 and especially 41 to 43, if you look at that today compared to some of that history, what do we see?

- Well, I think the first point is in addition to all of the challenges you just named Steven, supply chains have gotten a whole lot more complex. In 1941, it was possible to convert a Ford plant to making aircraft.

- Yes,

- You couldn't do that today with an F 35 or you couldn't even do it with drones. And partly this is because we have become accustomed in the last 30 years of untrammeled globalization to rely on just in time manufacturing, very low, very low inventories, no strategic stockpiles for the commercial sector and outsourcing of production for lots, widgets and component parts without which the big stuff doesn't run. And Apple has discovered this when they try to pull production out of China. It's not just about the assembly of the iPhone, it's the whole ecosystem of suppliers and skilled workers that that's surround it. And in many of these cases, we are discovering now the Trump administration is discovering points that we talk about in our book with respect to shipbuilding, for example, that the know-how exists in allied countries other than China, who's best at building ships, its South Korea. And this is why shipbuilding has become fundamental to our new understanding with our South Korean friends. I think it's a yes and proposition because this reindustrialization of America has become political. So, so we all want to enjoy some of the benefits that having a more industrialist society used to, used to bring. And there's a sense that there's a zero sum trade off here that in order to industrialize ourselves, we need to, you know, put up tariffs on our allies. We need to buy less from them. I think one of the findings we make in the book is this is very much a positive sum situation. We need allied support in re industrializing our economy. And it's not just the capital to rebuild shipyards, it's in many cases the skilled workers and managers who are going to train our people again. But it's also that in the 2030s, which is a window when deterrence is very fragile, we are going to depend on these allies for components that we can't make ourselves and figuring out a way to merge these supply chains. So in a sense, we are assembling what we can in the United States, but relying on allies for batteries or sensors or so forth when we need it, that these, these problems are worked out in advance. We can't assume that if a crisis breaks out, we will be able to scale production as quickly as we did in the second World War. And that also means a different approach to stockpiling. And it means building magazines of certain things that we know we might need, like long range precision munitions, insufficient quantities that we have enough because we may end up using them all up in the first few weeks.

- Harry, our title is a warning more than anything else. We look back on the arsenal democracy and think the United States was able to power a global war machine that defeated the axis in not too long a time in relative terms, but in reality, the US re-arm too late to deter that war and too late to keep it contained. The pin drop in the United States is the fall of France, which transforms the European balance of power. Fortunately, it doesn't seem to us that we've had a France 1940 moment yet. The Ukraine war is ongoing. Who knows how it might end, who knows when it might end sooner or later, but Russia did not transform the European balance of power in 2022 in a few weeks like Nazi Germany did. Yes, in Western Europe, this means that we have time. So what do we do with that time? Hmm, as we put it, we need a political mandate for the task in front of us to achieve deterrence that has two separate meanings. There's the meaning that I think we all intuitively sense and understand. We need Congress, we need the executive to gain buy-in from voters. We need our industrialists and our technologists today to buy into the problem as well and apply their forces to it so that we can build the military we need with intolerable cost. That's talked about quite a bit. What's talked about less is the mandate inside of our deterrent system where we need to align our military services, our procurement authorities, the intelligence community, people beyond the armed services who work in sanctions, work in tech policy, et cetera, on how we're thinking about driving forward different kinds of force development, buying different sorts of things that also requires a mandate from the top that also requires extensive coordination with industry for what it's worth. In the 1930s and 1940s, the Roosevelt administration failed in a number of respects to execute this and was bailed out by latent capacity, latent capacity that we quite rightly don't have now. Hence, that makes the second sort of mandate, the internal mandate even more important than it was during the run up to the second World War.

- Tell us a little bit about the, the research behind this, the evidence that's in the book, the kind of statistics or interviews or what makes your argument persuasive, what lies behind the arguments that you're making?

- Each of the chapters begins with a historical framework. History is not a crystal ball. It's not going to tell us who will win a conflict that's configured in a certain way. War games can't tell us that either, by the way. And it can't tell us when certain technologies will become deployable, but it can give us a sense of why certain functions matter in maritime conflict and how changes in technology force changes in doctrine. So we will talk, in the case of scouting, for example, scouting is the ability to see across an enormous expansive ocean and then to communicate once you see the target back to the shooter, scouting is largely a function of how far you can

- Shoot. Hmm.

- Over the course of 150 years. As a series of developments in naval gunnery allowed ships to fire and then eventually carrier based aviation to strike targets from hundreds of miles away. Scouting became increasingly difficult and increasingly important. If you can hide in a vast expansive ocean, you can potentially spot your enemy and completely obliterate them in a surprise for a strike. And the United States learned that lesson at Pearl Harbor. This has become even more the case in recent decades as we now have space-based reconnaissance systems and space-based communication systems. So this is just one example of a historical framework illustrating how technological change makes certain parts of the force increasingly relevant as we see the new technologies that are emerging in the next five, 10 years being applied. We, we don't use history prescriptively though, so we try to use it to frame questions about trade-offs and hard choices where actually the answers might be unknowable, like what the future of the carrier is, and then we will then use that framework to run through the various kinds of capabilities that exist. So we'll decompose the surface fleet, what makes it up, what are the offensive tools, what are the defensive tools? And we'll, we'll then look at the relevant technologies that are emerging and talk about how they could fit in based on what we know from open sources. The limitations to this work from a methodological point of view is that this is a work of open source research. We're not talking about classified capabilities. We don't have insight into these classified programs. And the only resources we have to understand China are that limited number of PLA texts that have come out and been translated. I have an affiliation with a amazing group at the Naval War College that does, I think, the best open source work analyzing these sources. So this gives us some sense of how China sees us, what aspects of our force China sees as vulnerable, and what aspects China sees as potentially threatening. Surprisingly, these elements, even though they're all separately discussed in great detail by others, haven't been put together in a single place. So it's, it's, it's that synthesis that I think makes this book distinctive.

- We're equally indebted to not just Admiral Ellis and Neil Ferguson, but a series of individuals across Hoover and more broadly in the policy world who Ike and I have gotten to know over the past few years who are enormous subject matter experts on each individual chapter in the book. During our peer review process, we relied them extensively. They gave us an enormous amount of feedback, which in fact prompted a top to bottom rethink of how we were considering the problems and cutting the text and produced what Ike and I, I think would characterize as a book. We didn't quite anticipate being so substantively rich and in some ways difficult to write, but thereby much more impactful by the end of it. In one of our production editorial meetings, one of these individuals said, once we cleaned up the manuscript, did, you asked a bunch of changes. There's nothing like this in print at this point because no one's written for a set of audiences like yours. We are not writing simply a pop policy book about the China problem and what we need to do about it, the gray zone deterrence issue or something like that. Nor are we writing a very specific technical guide to air naval combat in the 2030s and 2040s in turn. This isn't a think tank report. I've written plenty of them in my life, so it was my co-author. Those have a very specific style and format. They come with a series of very granular, aggressive policy recommendations. What we instead do is we demonstrate why everyone's job matters in the deterrent system. We tell the program officers who are working on procuring this or that kind of weapon, this is why you need to do your job and this is why your job, the 1% half a percent contribution that it plays into our military deterrent system is enormously consequential. And it gives people like that in academia, in the private sector, in uniform, in and out of government a weapon to shape the debate and in turn a common language to really talk about, yeah, our system against the Chinese that doesn't exist yet and it's badly needed in 2025.

- Let's talk a little bit about the two different systems and then we'll open it up to the audience. So it's clear that the Chinese model and the US model are not the same the way the US goes about building things or commissioning things or deploying things versus the way the Chinese system goes about this. We imagined that our system was superior in this regard. We participated in China's aggrandizement. What is it about their system that seems to work? What is it about their system that we might wanna adapt? Was it about their system that we would not wanna adapt? And why when the systems come into competition short of a hot war, God forbid, what is it that we can learn from the contrast of the systems? And where are the systems either in overlap or there's some emulation adaptability involved there?

- It's an important question. We wrote this book with help and advice, but based on open sources. And I can tell you that our counterparts in Beijing have read all of those same open sources. So they have, they have a very detailed understanding about how our military is organized, about our strengths and about our weaknesses. They are keenly aware of our strengths and when we have demonstrated them in Desert Storm for example, we have documentation of them writing about just how formidable we are, but they can also see that the ready reserve force, which is essential to our maritime logistics, is a fleet that was largely built in the seventies and eighties

- And

- Is in dire native repair and is running out of Mariners. So they have built their own system, not accidentally to optimize for strengths that correspond to our greatest weaknesses. In a sense, that's a standard second mover advantage. And there's lots of examples of this from military history, some of which we, we talk about in the book, but that's significant. And if we want to respond accordingly, part of the challenge is one-upping them and in this next offset over the next five, 10 years, investing in the right capabilities and systems so that we can hold them at risk where they are relatively weakest, they are very good at setting numerical targets and meeting them. So every year a decision is made somewhere in the bowels of the Central Military Commission, how many ships, how many missiles, how many aircraft, how many drones, how many factories, how many officers. And then that number of things are made or that number of officials are promoted or so forth. It's, it's very top down in that respect. This principle applies across their economy, by the way. And this is a tremendous asset that the United States will not have, and this is because we're a free society with a limited government and Congress controls the purse strings and so forth. It is harder to assess the qualitative capability. And I think we have to assume that on some level there is a trade off between sprinting to build as many of the thing as possible and having them be relatively good. There is some uncertainty here and the details such as there are known tend to be classified, but that is definitely a strength. We should treat it as a strength. And then the, the third strength that I would highlight getting back to the supply chain's point because it is so important, is that in our system we rely on private contractors to do the hard work of building the stuff that our military uses. And as Jim Ellis told us in one of our early meetings for these contractors, this is a business, not a religion. They respond to incentives to demand signals that they get from Congress and from the Pentagon. And if they don't get the demand signal, they don't hire train, retain the workers, they don't retain the, the manufacturing lines and keep them warm. And this is not just true at the level of the suppliers, which are really like the final assembly, but at the level of the subcontractors that make all the components. This is a problem because as we have discovered making ammunition for Ukraine and in other areas, it's not as easy for us to scale production of some of this stuff as we would like. And it's because we haven't paid attention to the effects of our more market oriented system on those lower levels of the chain. I think there are ways that we can, you know, mitigate some of those vulnerabilities without enormous cost or without completely changing the way we structure our economy. But there are specific interventions, policy interventions that we do have to make. And that theme comes out across the book.

- I think there are two fundamental similarities that are worth highlighting because they demonstrate throughout our book that the United States faces choices. But those choices can be made to gain competitive advantages that are enormously meaningful, even if the cost behind them in total is actually quite marginal. For one, we in the United States and the PLA in China think about combat from what we understand in the open source in a pretty similar way, which is remarkable. It was not true say in the second World War in the runup to it, that the axis powers and the allies thought about combat on the ground in the air, on sea. In this similar of a manner, there were radically different doctrines, radically different force structures. America and China have different force structures, but their emphasis on scouting and strike their emphasis on what's called a reconnaissance strike complex and technical parlance is actually remarkably similar. This is no accident. Of course, they've all read the same things. They've all, they're all drawing off of the same evidence base. The Chinese has seen how effective American weapons are both in Ukraine, 1991, 2003. Yeah. This also at one level up confirms to us that despite the fact that China is an obvious authoritarian power, we are a democracy despite the fact that one man chairman Z matters a lot more than anyone else. China requires an incredibly complex strategic bureaucracy. There are a bunch of people in this country that spend day in and day out their time focusing on very specific elements of the China problem, the Russia problem, other problems. They're locked in basements and undisclosed facilities. They're incredibly smart, they're global subject matter experts on these issues. The Chinese counterparts of these people are just as good and they feed into an overall bureaucratic structure. But we know something about our bureaucracy, we know something about bureaucratic competition throughout the Cold War. It's that bureaucracies for a variety of strange structural reasons. Psychological ones tend to make suboptimal choices at times. They tend to allocate resources in very problematic ways that create path dependencies that allow someone to gain leverage over them In this context, arguably China's nuclear breakout provides an excellent example of this. Why? Well, China's sprinting for some kind of nuclear parity with the United States. China has developed a large scale, ground-based launch system based in the west of the country with hardened silos that are very much reminiscent of what the USSR deployed in the seventies and eighties. It is aggressively trying to modernize and deploy a nuclear powered nuclear armed submarine program for secure second strike capability. It is also pursuing different forms of non-strategic nuclear weapons that it can use to potentially manipulate escalation thresholds. But when we drilled down into it, some of the smartest people who we talked to said one of the best explanations here is that the guy at the top seizing ping said, huh, why did the Americans have so many nukes and why do the Russians have so many nukes and why do I have like 20 that's not quite right. I need to build more nuclear breakout is incredibly costly. It takes a lot of time, a lot of technical effort, a lot of focus that distracts from other priorities. It's a trade off, it's a choice. We in the United States can do things with our forced design to signal to the Chinese that we can find their nuclear armed nuclear powered submarines that we can detect track and potentially intercept some of their missiles that we can do hard target things in Western China. If we climb this far in the escalation ladder that disrupt their second strike capability on the ground, that forces additional spending choices and additional irrationalities in the system. That's one example. But in the round, the United States doesn't have to spend that much money activating these perception problems that we can identify on Beijing's part that is a route to preserving deterrence without breaking the bank.

- Yeah, I'm mindful of the fact that the, that we underestimated how quickly, what kind of scale and what type of quality level the Chinese could build what they've built. So no market economy the same way as ours. P and l could be suspended, bank loans could be made that were maybe not gonna be paid back or not gonna be paid back anytime soon. Workers could be moved around whether they wanted to be moved around or not and I could go on, right? And so somehow they were able to achieve what they've achieved now to the point where you're talking about the kind of threat potential potentially prevailing against the US in a war the US has generally speaking, considered itself to be an advantageous position with the free and open society, with the market economy. Is this correct? Is the Chinese system somehow able to do things that we still can't explain, but the market system is a superior form of delivering national security at scale and price that taxpayers and citizens are willing to absorb? Do we need to become more like the Chinese system in procurement practices, in centralization, in command from the top in not considering p and l in order to compete with them? Do they need to be become more like us in order to be able to prevail in this competition from a systems to systems? So you're, you're neither American nor Chinese. You are neutral third party observer looking at the system to system competition and you want to talk about the systems and how they work or fail to work.

- It's a good question. I'm curious what Harry has to say. I think it's too early to tell. They clearly have a better model for making lots of stuff. And what they have not yet shown is that they can achieve technological parody or overmatch in some of these key areas of the soft tissue which maintain, maintain our advantage.

- For example,

- For example, space undersea and cyber, we have significant advantages in launch capability. We have significant advantages thanks to SpaceX. The American private sector is leading in proliferated satellites in low earth orbit, which give us new ways to communicate in resilient ways to see the, so we're not dependent on a small number of very exquisite satellites. Our ballistic missile submarines remain the best in the world. Their anti-submarine warfare is improving but not fast enough for Cxi Jinping. And you know, the details in cyber are highly classified, it's public knowledge that they have penetrated us critical infrastructure. So clearly we're both quite good at it, but I think it's hard to explain the broader attitude of the senior people in the United States military on this problem without assuming that the US is really good at offensive cyber itself. Okay. So I think it is yet to be proven whether they can overtake us. Xi Jinping has clearly indicated that technology is the, the big focus of the next five year plan that's not just commercial. It's because he recognizes it's central to the military balance. And it's not just a question of inventing the tech in the lab, it's a question of diffusing and deploying it through the military system. They say they're trying to do that with ai. I'm not so sure remains to be seen.

- I'm not a China specialist by any means. But to your question, there are things that we can obviously learn from the Chinese, particularly in military industrial contexts. And this isn't necessarily a state capitalist issue or a state capitalist advantage. It's an accountability one. Why? Well, because the American procurement systems we all know has been fundamentally broken for a very long time. Almost every major procurement attempt for aircraft submarines, large warships tanks, helicopters since, depending on how you cut it, 1995 or 2005 has been delayed moderately to grossly over budget and had to have gone through a series of design changes that created a product that was nothing like the original or even worse, just didn't work at all. Like say the electoral combat ship. Yeah. Ships that were retiring three or five years after we built these hulls. Why does that happen? Partly because in the American procurement system, up until the Trump administration started to address this a few weeks ago, accountability and responsibility for budgetary allocations and for program management we're just not linked up at all. You would have program executives come in for a few years, oversee a program, takes you six months, they get up to speed, you're there for another 18 months and you're off another rotation. Someone else fresh comes in. These one star barons is there sometimes called in the buildings in China. They don't seem to suffer from this problem. It's curious that the Soviets also didn't fully suffer from this problem, at least for the Navy. Why? Because they had institutional continuity, not just at the top, but for the people who are tasked with delivering, say very large numbers of frigates, new submarines, more missiles. Now the Chinese have certain levers that they can pull to induce compliance, shall we say that a free and open society simply doesn't. However, I am not convinced that the threat of force is what's necessary to make sure that the Pentagon procurement bureaucracy does its job effectively, that prime defense contractors are transparent about pricing and work effectively with that bureaucracy and that newcomers to the market interesting. New companies can fit into the system. I think it's just simply a matter of transparency, incentives and accountability. The fact that we're not good at this isn't necessarily a function of capitalism. The fact that the Chinese are good at this isn't necessarily a function of state control over their economy, but we still need to catch up to them.

- Okay, yeah. I have this alternative history of the world where Edward Snowden gets captured by a cult and disappears. And as a result of which China lacks capabilities to penetrate American systems or mount signal intelligence, the situation they were in before Snowden, the same cult captures Elon Musk before 2010, when China had no electric automobile industry whatsoever. No really electric tech stack revolution. And Elon disappears into the, and as a result of which China doesn't get what Elon delivers for them. And the third member of the cult is Tim Cook. And he also is captured really early on when he was still COO of apple. And as a result of which China doesn't get Shenzhen logistics skilled workers and multiple hundreds of billions of investment in supply chains and industrial capacity. So the three of them get captured and are forced into this cult from which they can't escape. And I think, you know, why wasn't I thinking this way and why didn't I form a cult, which was like a cutout cult, not a real cult in order to affect this alternative history where you roll things back

- Alternatively, why hasn't the CIA done this already?

- I I'm not gonna comment on that because I have a lot of friends there, but certainly the alternative history conversation has come up. I mean, I've brought it up and so the, I'm not casting aspersions on any of these people. They're enormously talented people in their own right. Elon has built our electric tech stack. Without Elon, we wouldn't have any whatsoever. The fact that the Chinese also have one as a result of that is what I'm speaking about. But I don't know where we would be without Elon Musk and, and certainly Apple has delivered quality of life for the American people and beyond in ways that were hard to imagine before that company's success. And so this is, this is not personal, it's just business as they used to say. But no, it's, it's, my point being is that we've contributed to this situa to the problem. And so the the thrust of your book is how do we contribute to the solution of what we've gotten ourselves into? Nothing. No, we don't wanna take anything away from the Chinese. It's phenomenal what they've achieved. Many other countries could have invited Elon or Tim Cook or whatever to visit them and would not have achieved what the Chinese have achieved. So we can't say that their diligence and ingenuity and everything else is a small factor in this. It's a colossal factor. But I just wonder, thinking about it this way, are there any people on the Chinese side that could contribute to us? Are there any processes on the Chinese side that we can borrow? Are there any kind of reverse snowdens, reverse Musks, reverse Tim Cooks, you know, there's this thing in East Asia which called judo and it's one of the most brilliant martial arts. All martial arts are brilliant, but Juno is about using the strength, the capabilities of the adversary against that very adversary, right? It's a version of sort of lenins, the bourgeoisie will sell us the rope that will use to hang them. And you see where I'm going with this. And so I look at the Chinese achievements and I say, how do I get some of that now onto my side, the way that they got some of that from us? Is that a wrong way to look at this? Is there anything in the book that would guide us on this question? Have I lost my mind?

- Well, there's nothing on this in the book, Steven. Sorry to disappoint.

- Well give it to us now.

- No, no cults and counterfactuals. Okay. Look elsewhere. But it's a, it's a fascinating and challenging question and I wish that I could give an easy answer to you and reel off some names. I think I'm sure that there is, there are many among the hundreds of thousands of students from China currently studying in American universities who would happily set up shop in the United States and move their families here and contribute to this enterprise if there were a pathway for them to do so safely. It involves bringing their families here, not just giving them personally a pathway to remain. I'm not optimistic that there is a political road in that direction, but I mean, some have joked to me that China produces so much AI talent that maybe the US government should just pay some of these people to hang out in a office park outside Chicago and play darts and ping pong for five years.

- Yeah, that's what they do in Abu Dhabi. Now it's a good thought.

- So I I I don't have a good answer for you in the, in the judo move, but I, and and partly it's because China has always been much more sensitive about knowhow going in the other direction. Yes. And US tech firms learned this when they tried to get into China. We have learned this through joint ventures in many industries. Yes there is knowledge that goes both ways, but it always tends to be asymmetrical and no matter how you write the contract. So I'm not optimistic that there is some silver bullet here, but I do think that there is another form of judo which is to do with cooperation with our allies and partners precisely because China is so fixated on preventing us from having advantages. They're weaponizing rare earths, they're building the basis for a sweeping export control system that goes far beyond anything that we have to or would dream of having that would enable them to turn off the flow of specific technologies and products to us. But that threat applies to our allies and partners and lots of neutral countries too, not just us. And the fact that China has shown its cards and revealed itself to be unreliable as an economic and technological partner in this way in the process of its trade negotiations with Trump is having political effects in Europe, in Japan and elsewhere that are very visible, that are moving very quickly witnessed what Taichi san the new Japanese prime minister is doing right now. So the opportunity here is not necessarily to get know-how from China that we should explore ways to do it if we can. It's it's to leverage this allied scale and find know-how in our allies and put it to work revitalizing this enterprise,

- Finding a Chinese Snowden as a task again for those in Langley, Virginia. But there are I think certain lessons and elements that we can probably, if not copy then at least replicate with American characteristics. For one, we can like they do look at foreign combat experiences and much more effectively distill concepts of operations from them and test them. This seems like a rather arcane military technical thing, but it's not at all why? Because this is how the Chinese have figured out how to build the force that is so threatening that Ike and I wrote Arsenal of democracy. The Chinese haven't fought a large scale air naval war ever, yet they've been able to make a military that is still not likely to win one in our reading, but that conceivably has some probability of victory, one in five, one in 10, one in 20. That's much better than they have any right to do given their lack of experience. Okay. That process can be copied and replicated on our side. We can similarly look at how they've been able to transform themselves into a tier one intelligence actor, replicate some of that ingenuity, knowhow and aggression operationally, they're not simply operating with overseas networks anymore. They're recruiting and developing assets just like the Americans and dare I say it just like the Russians have done since the Cold War. That's a mentality question, being able to accept risk, go out and attack your adversary.

- Let's open it up to the audience. We've got about 20 minutes or so for audience questions. We're gonna have a microphone so when I call on you, you're gonna wait for the microphone. That's the bargain. If you don't wait for the microphone, we're gonna go to the next person. Not really, but you gotta try deterrents if you can. Yes. We'll go to this young lady in the front and then the young lady right behind her and then the gentleman in front of them.

- Thank you for the excellent research. I'm very curious about two areas to play adv devil's advocate here. So first of all, how do you see the impact of China's perception of the nuclear family and the social credit system on all of these areas? Because I think that's a very underestimated area. Sure, in the US we have the credit score, but the Chinese social credit system sees to that if you're a model citizen, you get direct benefits like cheaper car loans or your child has better chances at going to better university versus being a bad citizen. Your child has punishments. And it has also been my experience when I studied in, lived in London that I met daughters of CCP members who said, if I don't return to China after my studies, it's going to negatively reflect on my family and I don't want them to suffer. So even though they might want to go to the west, they usually choose to sort of stay loyal to their family and return, which of course you could argue is a negative thing. But if you look at it in the spectrum of sort of the country as a whole advancing, it does make sense in a sort of devil's advocate way. And the second thing is obviously the nuclear family, where China realized that their one child policy, which led to an overpopulation of men has hurt the country as a whole. So they made very aggressive efforts to sort of counteract that now by like really emphasizing how important it is that like women get married early and have children. Obviously here we don't have this level of insane social pressure anymore. But arguably that's kind of hurting us in this international competition because arguably you do need new people to have a strong population and you do need devoted loyal citizens whose have it in their interest to advance the country. So obviously a very controversial question, and I don't think there's a perfect answer to it, but based on your research, how do you see this country could become stronger and improve by maybe adapting certain elements of China's policies?

- Thank you for the question. I, I think it's a, it's a astute observation. China has tools to coerce its people, those in uniform and their families and so forth that we don't have, that we would never want to have in this country. We have an all volunteer force and we like it that way. And similarly, I don't think China is likely to be moved in a conflict by the fear of a few thousand casualties in the way that we are or even a few tens of thousands of casualties. I think what, what China fears both the regime and the people is systems collapse. And what is at stake in a war with the United States, God forbid if one should ever happen is not just the death of a a a few tens or hundreds of thousands of young people. It's systems collapse. And that is partly because it is just so unimaginable that our two countries could become locked in that kind of confrontation. Once you imagine that that Pandora's box is opened, all kinds of horrific escalation pathways become possible. So for deterrence, I think the lesson is we need to keep the focus on Xi Jinping, the man and on the elite leadership layer to suggest that any, any confrontation could escalate in ways that would likely get out of control. And that's why we share an interest in not going down that road. I think there is a pathway in some scenarios for the United States to speak directly to the people of China, but that would have very significant effects essentially. This is, this is not a question that directly bears on deterrents other than that we have to focus on the system level competition.

- Yes ma'am. The young lady right behind. And then the gentleman in the front and then we'll go to the back.

- Thank you very much for the book and amazing research, a very comprehensive project. I have two question and I try to be brief that, so one is about the new alignments and new allies that we are trying to expand and advance under the sort of a common adversary of the problem of China, for instance Saudi and all the new sort of countries. And, and I'm thinking that learning from the past, how we are really strategizing our new alignment with these countries that the interdependency with these countries are evenly defined. So then for instance, 2030 that you mentioned, the if new opportunities for these countries open up, they still, they're still obligated to be sort of dependent on us. So the interdependency that if we, if they help us, we help them in a way or we are embedded in their countries in a way that they cannot realign themselves given the opportunity presents 10 years from now. And the second question is about, we talked about heart powers like navy and all, you know, sort of space and all, what about biotech and bio weapons? That is, and apparently at least it's something, it's a form of weapon or a strategy that China is set that is ahead of us. And did you guys even even consider that and think of that as a form of, you know, in this system and in larger framework,

- Maybe I'll talk neutrals and you talk WMD. So two very, two very thoughtful observations. Anytime the United States and China have any kind of con confrontation, third countries become collateral damage, but they also find opportunities. And this question of who would be neutral in the US China crisis? Would the neutrals band together as one or would they form blocks? How would they try to balance between the two sides? Because in the economic domain at least they would want good relations with both. This is a critical question which has I think been under explored. Saudi is just one example. I mean imagine a world in which China is cut off from the global oil market. China consumes over 13 million barrels of oil a day. What happens if to oil prices if they can't import? Everyone has a stake because there's only one world oil market. There's only only one world copper market. There's only one world market for soybeans and pork belly and so forth. So I think the basis for us cooperation with these neutral countries has to be twofold. One relates to technology and one relates to our economic understanding of the day after. And with technology, the fundamental trade off is that if you give a neutral country access to the tech, it could leak to China. But if you don't give them access to the tech, they could join China's networks. We see examples of this in the Middle East all the time. The Trump and Biden administrations have different views on this, but I think it's fair to say that if you want the neutrals to cooperate with you, it helps if they're on your networks, your space networks, your undersea cable networks, your cyber networks, your payment networks and so on in the trade space, I think the key is to understand that any US China rupture would be one of the largest exogenous shocks that has ever hit global markets. And the uncertainty would be enormous and very possibly the markets would respond more to what the United States was doing than what China was doing because China might be playing a diplomatic game that tries to make it all look like America's fault and get the developing world in particular to side with them. If the United States doesn't want to push these countries into the arms of China, what compromises does it have to make? And one of them may be, we don't have a problem if you sell to China or if you buy from China, but what is the asterisk, what's the catch here? What is the minimum bar that we want these countries to clear? I think it probably has to do with controlling their borders. So not re-export our tech to China if we say you can't and being honest to us about what you're buying from China and trans shipping onto us. But that conversation hasn't been had and I think it matters a lot because if you think back to the World Wars I Andi, the neutrals head agency, the United States was a neutral. We had a whole lot of agency in the opening parts of both of those wars. And the neutral community would be larger and more diverse and more influential in a US-China conflict than in the first half of the 20th century. Let me hand it to Harry to talk about bio.

- The the difficult part of biological threats and chemical threats, to be honest and part of why we don't address 'em directly in the book is you are operating at a very high degree of classification and compartmentalization. We haven't seen large scale chemical deployment on the battlefield since the Iran Iraq war. Despite some trace cases in Ukraine, the Russians have not used either bio weapons or chemical weapons at large scale. We've never really seen a bio weapon deployment aside from what in stylized depictions we might call certain terrorist incidents. That being said, particularly on the bio wm, the bio weapon side, we can very much conceptually link them to other thorny nasty elements of the classified deterrence problem. Like offensive cyber, we have evidence of Chinese offensive cyber activity against American targets. We have some extraordinarily elliptical evidence of American offensive cyber activity against Chinese and Russian and Iranian and North Korean targets. If one were to look hard enough, one can identify the contours of a bio infrastructure in the United States used for classification of threat and for antidote development to threat. It is not a coincidence that the Chinese and Russian bio programs are characterized in that way as well. The difficulty, however of operational deployment is bio development is not nearly as cut and dry as we think. I think there's a misconception in the open source that one could engineer the perfect virus just to target certain Americans or certain types of Americans of a certain demographic or in a certain area and cause enormous devastation and disrupt the country. Maybe that's possible just like maybe a national scale cyber attack that destroys the entire electric grid. It's also possible we have to account for those issues, but it takes a lot of investment to develop tools in the bio space that aren't always that accurate. We can see use cases, say a Chinese bio attack on Taiwan as part of invasion against which all of the invading forces inoculated. But again, these are not exactly controllable weapons once they're out of the box. The COVID-19 experience demonstrated that you can know a lot about a virus and it can run wild in a population anyway and you have to take drastic measures to contain it. Hence there's an enormous amount of gray risk around bio issues that just doesn't lend them to being discussed and integrated as substantially into the deterrence picture. At least in the open source.

- We'll go to this young man in the front and then we have a young lady in the back and then we'll see if we have time left.

- Well first I want to thank the three of you for the lively discussion and since we're deep in the heart of Silicon Valley. I wanted to bring AI into the conversation from two angles. So one is you talk about surge production capacity and the other one you touched on the situation with drones and, and those kinds of things that we're learning from the Ukraine, Russia war. And so I wanted to see how bringing AI into those two aspects would, would transform the situation from a couple of angles. So one, to produce things in the us given the cost of labor here, it's probably five or six times more expensive per person to do it. So we're just at a major disadvantage to producing the munitions in any kind of cost effective way. However, if you were to bring AI based robotics into the equation, it's transformed, right? You might be at cost parity or you might even be at an advantage if you, if the Chinese can't do it. But frankly, also, it doesn't seem that we need to worry about whether the Chinese are, are producing as much as us. It seems like what the, at least the Taiwan strategy is to make it a porcupine, right? We're not worried about China trying to invade the United States, right? It's not that kind of scenario. So that takes me to the second question or second aspect of ai, right? That if you are able to fill the straight and make Taiwan covered with autonomous sea air, land drones that are always on, always loitering, always vi vigilant, right? It forces China to do two things. One, they have to now have kinetic firepower to try to shoot as many of these things down. They have to invest a lot in their missiles and their offensive weaponry. And the other one is they have to harden all of their targets themselves now because they can't use electronic warfare or other jamming or these other things to, to kind of mitigate that because the AI is able to, to still follow through on its missions. So does the book go into this aspect and how the US can really leverage our technological lead in AI and, and really leverage it here to kind of in the next five or 10 years, close those gaps quickly?

- So I'll be brief and I'll hand it to Harry. We don't talk about speculative tech in the book, we talk about tech that is either already basically productizable or will be soon because we're interested in this five to 10 year timeline. I think the first integrations for AI are most likely to be in cyber. And fundamental questions remain about just how autonomous these bots will become, just how much better, if they are better they will be than, than human hackers and how they will affect the relative balance of offense versus defense. I think this matters fundamentally, and we're going, we could be seeing this very soon in terms of robotics affecting supply, sping shortages and so forth. China's investing in robotics too, and I think this is a much longer term question, the outcome of which is, is much harder to predict. AI does have big implications for decision support for intelligence, and I think we will continue to explore that. But there are also counterintelligence applications like data poisoning. The effects of AI on the strategic balance at the nuclear level are also very significant. There's a lot that we don't know about this, but I think it doesn't negate the need for the physical platforms that are there present in the region that will deliver masks to the target.

- The problems that you've articulated that you think are AI problems are not AI problems. The Ukrainians have found that out almost immediately. I do a lot of work independently of this book on the Ukraine problem set. The Ukrainians aren't basing their drone ecosystems on automated purposes. Automation involves a very small amount of track to target and engagement. What they found in fact is that you can talk about automation all you want, but you still need batteries. You still need explosives, you still need warheads, you still need seekers. You still need all these traditional guidance systems, and you can actually still jam things at terminal points if you have a powerful enough repeater or emitter depending on the munition that you're dealing with. All that is to say you are dealing with a full stack technical problem in military terms that we actually understand the parameters of quite well. How does this connect quite directly to our book? We can talk as much as we want about a porcupine strategy, something that has somewhat fallen outta favor in the current administration's parlance, but that essentially involves what you've articulated in the end. However, if the United States does not have a credible force that can deter Chinese action against Taiwan elsewhere in Asia, and that can credibly threaten to defeat at tolerable costs that action, if war comes, then Taiwan's capabilities are relevant to killing Chinese soldiers, but not strategically relevant. Taiwan cannot win without American and allied support. That's the fundamental takeaway of our text, that this narrow focus on the Taiwan deterrence problem on Taiwan capabilities might be helpful in policy terms to a certain extent, but strategically, we need to make sure that we are ready and prepared to fight when we need to.

- We're now in injury. Time means someone got injured during this presentation, and so as the moderator, I'm gonna add a tiny amount of injury time to the, to the, so this will be the final question. What's happened in life is that everyone has aerated to themselves. Two questions used to be one question was considered sufficient if you got called on now, if you get called on automatically at least two, which deprives everyone else who's got their hand up to ask one. So I have to figure out how to manage this better because I failed. We'll go to the young lady in the back and then we're done.

- I had two questions. I'll ask one. I did have two questions. So when you look at Brinksmanship and you look at the Cold War and what happened then, you know, we have a much better understanding of the US of when we might press that red button when we might go forward. I, I think China from our studies is so much more willing to lose so many people, millions of people, not just hundreds of thousands. They've been shown to laugh that we change political leadership every four, eight years. They have such a long view. I, I guess my question is how are they, where would their leverage be? Where they would be able to say, you know what, we're gonna call war on this because we have leverage in electrification or in another area where they feel like they have leverage and they will go to war. Like what and how did they get that approved? So is it one person? Is it, you know, a group of people? How is it different from how we view war and also how they view people. We cared in World War II if a woman, a, a mom lost five sons. I don't think they do. They are willing to expend those people. So what, where did they come in and say, we're willing to go to war?

- Yeah, I'd like to know the answer to that also.

- I don't know where their line is, but I think we should stop thinking about them. It's about him. The decision lies in the hands of a single man who's got his hold on the reins of power. As far as we can tell, though, there has been some, some turmoil in the leadership of the Central Military Commission, so who knows? But we should assume he does at some point. He will have to retire, even if he lives to 150 as he seems to think he will. He'll have to hand off some of the day-to-day, but he'll be forced to to others. So he's thinking about this from a deeply personal perspective about his legacy, but also about his life and limb and that of his family as he enters his golden years. And so we should stop thinking about this problem as how do the American people deter the Chinese people? They don't have a vote here. The question is how we deter Cxi Jinping and we need to show a credible combination of resolve and restraint. We have to communicate what we care about and why. And we have to lead him to understand that there is a pathway to get most of the things that he cares about, which he calls national rejuvenation that are in line with what we will accept. And then we need to make him believe every day when he gets out of bed. Not today, it's been 4,753 days since he took over the Central Military Commission. That's 4,753 days that he has gotten out of bed. He's lived his day and he's gotten in bed at the end of the day. And he hasn't attacked us forces. He hasn't attacked us, ally or our partner. That's, that's the task. How do we keep doing this one day at a time?

- Do I, does my intervention count as the second question at this point or

- No? You can certainly speak to the question. We are an injury time, however,

- And I'll, I'll keep it, keep that in mind so that no one else has to get carted off. I think we should be skeptical of the i the Chinese claims that they're willing to take an enormous amount of pain, and I think we should be skeptical of Chinese claims that the American and system and democratic and western systems are shortsighted. The Ukraine war is a laboratory for many things, for military technology, for operational concepts, for strategy, well or poorly applied. It's also a laboratory for how societies respond under pressure. Ukraine and Russia are both societies that were in profound demographic crisis before February, 2022. This has accelerated. This war has accelerated such a crisis. There are not that many men in both countries. Their population profiles are incredibly narrow in the middle during the collapse of the Soviet Union during those years. And yet both these societies, until today, for every day of this war, and by my reckoning at least I know there's some debate about this, but by, by rec, by my reckoning tomorrow and the day after and the day after, we'll send their men, young, middle aged, some old to fight and die in the mud and they will bury them with flags on their coffins. Without question. The Ukrainians will do this because this is their land and this is their life. Now, I ask you for a China that as we heard before, experiences of variety of demographic problems for a China that's in many ways in urban areas, wealthier and more developed than Russia and then Ukraine. Are Chinese parents seriously willing to feed their sons into the meat grinder to fulfill the ambition of the man? Who decides when the chips are down, are they going to take day after day of horrific conflict? Are they going to risk the lights going out in their cities? Are they going to risk the food supply collapsing in their cities? And are they going to risk the suns that they bore and that they wish to marry and grow up and have good families and good lives coming home in body bags or not at all? I hear a lot from critics of our argument that the American people won't stand for a war over Taiwan. We won't send our sons and daughters to go fight over this rock. That means nothing to us. I put the question to the Chinese and you know, I am not sure if we would see them line up to fight and die in the mud. I'm less sure about them than I am about us.

- Ladies and gentlemen, arsenal of democracy, Ike Freeman, Harry Haem. Let's give it up.

The US military stands at a moment of profound risk and uncertainty. China and its authoritarian partners have pulled far ahead in defense industrial capacity. Meanwhile, emerging technologies are reshaping the character of air and naval warfare and putting key elements of the US force at risk. To prevent a devastating war with China, America must rally its allies to build a new arsenal of democracy. But achieving this goal swiftly and affordably involves hard choices.

The Arsenal of Democracy is the first book to integrate military strategy, industrial capacity, and budget realities into a comprehensive deterrence framework. While other books explain why deterrence matters, this book provides the detailed roadmap for how America can actually sustain deterrence through the 2030s—requiring a whole-of-nation effort with coordinated action across Congress, industry, and allied governments.

Rapidly maturing technologies are already reshaping the battlefield: unmanned systems on air, land, sea, and undersea; advanced electronic warfare; space-based sensing; and more. Yet China’s industrial strengths could give it advantages in a protracted conflict. The United States and its allies must both revitalize their industrial bases to achieve necessary production scale and adapt existing platforms to integrate new high-tech tools.

FEATURING

Eyck Freymann is a Hoover Fellow at Stanford University and a Non-Resident Research Fellow at the U.S. Naval War College, China Maritime Studies Institute. He works on strategies to preserve peace and protect U.S. interests and values in an era of systemic competition with China. He is the author of several books, including The Arsenal of Democracy: Technology, Industry, and Deterrence in an Age of Hard Choices, with Harry Halem, and One Belt One Road: Chinese Power Meets the World. His scholarly work has appeared in The China Quarterly and is forthcoming in International Security.

Harry Halem is a Senior Fellow at Yorktown Institute. He holds an MA (Hons) in Philosophy and International Relations from the University of St Andrews, and an MSc in Political Philosophy from the London School of Economics. Mr. Halem worked for the Hudson Institute’s Seapower Center, along with multiple UK think-tanks. He has published a variety of short-form pieces and monographs on various aspects of military affairs, in addition to a short book on Libyan political history.

Stephen Kotkin is the Kleinheinz Family Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution as well as a senior fellow at Stanford’s Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies. He is also the Birkelund Professor in History and International Affairs emeritus at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs (formerly the Woodrow Wilson School), where he taught for 33 years. He earned his PhD at the University of California–Berkeley and has been conducting research in the Hoover Library & Archives for more than three decades. Kotkin’s research encompasses geopolitics and authoritarian regimes in history and in the present.