- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- State & Local

- Political Philosophy

- Comparative Politics

- Empowering State and Local Governance

- Revitalizing American Institutions

The threat of a government shutdown makes everyone shudder. Why? Because we depend on government to keep our lives orderly. From traffic laws to schools to everyday business transactions, we expect government to be there to enforce the rules and provide the funding to keep public services flowing. The more our individual lives depend on government funding, the greater the effect of a shutdown.

Native Americans are especially hard hit because individual tribal members and reservation economies are funded by an alphabet soup of federal agencies including BIA, BIE, BLM, DoT, FWS, NPS, HUD, DOE, DoEd, HUD, HIS, ONRR, OSGS, OST, OSGS, and BuRec. In 2024, Congress approved about $32.6 billion in funding and assistance intended to benefit tribal communities across such federal agencies (including health care, infrastructure, education, transportation, broadband, and other services). Because tribal economies depend so heavily on the federal government, shutdowns leave tribes with impossible choices regarding whether to keep clinics open or furlough staff; run school buses or conserve fuel; and continue patrol shifts or park their cruisers.

This past fall, the government shut down for forty-three days, the longest shutdown in US history.

During that shutdown’s first month, a daily continuity index monitored service status across 118 reservations. The index comprised eight service categories: Indian Health Service care, WIC nutrition benefits, Impact Aid for schools, Bureau of Indian Affairs program operations, Bureau of Indian Education schooling, core tribal government operations, public safety, and utilities. Evidence from a sample of 118 tribes shows that some tribes scaled back far less than others, but more than 82 percent of the reservations maintained their services, reflecting that even during a severe federal shutdown such as the country experienced last fall, many tribes found ways to keep most services operating.

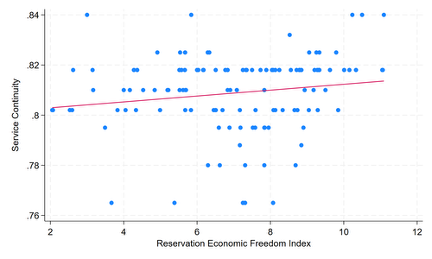

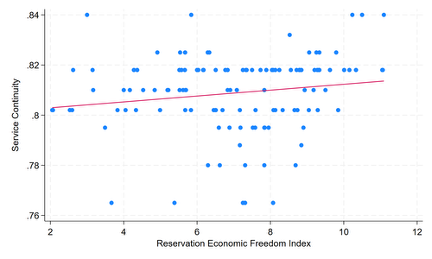

Figure 1 shows levels of tribal service continuity plotted against the Reservation Economic Freedom Index (REFI) for each reservation. The REFI was introduced in the peer-reviewed journal Public Choice in 2023 and was recently expanded to include a total of 123 tribal nations. The index measures broad institutional quality, including self-governance authority, judicial independence, commercial codes, and legislative transparency, not all of which directly relate to government operations during a shutdown.

As the Public Choice article explains, “Economic freedom rankings provide critical information to scholars and policymakers to understand the effect of institutions on economic growth.”

Figure 1. Institutional Quality and Shutdown Resilience

In figure 1, each dot represents one reservation. The upward trend (the red line) shows that higher REFI scores correspond to higher service continuity during the shutdown. Most reservations maintained service continuity around 82 percent, reflecting that even during a severe federal shutdown, many tribes found ways to keep most services operating. (The relationship is positive (p = 0.068): each additional REFI point corresponds to about 0.12 percentage points higher continuity on the 0-100 scale.)

The observations are scattered because service continuity depends on many factors beyond institutional quality. Scores cluster within a narrow band. The relationship, however, is significantly positive within conventional significance levels. It shows that a 10 percent higher REFI score corresponds to about 1 percentage point higher service continuity during the shutdown.

That 1 percentage point makes a big difference where poverty is widespread and alternatives are few. That 1 percentage point translates into after-school programs continuing, late buses still running, and clinic pharmacies staying open all week instead of closing early.

Reservations with clearer institutional frameworks and more local authorities kept more services running because better-defined rules let leaders adapt when federal offices go dark. Modern commercial codes and efficient procurement systems let councils reallocate available resources to priority needs without navigating layers of federal bureaucracy.

How did tribes cope during the shutdown?

Two institutional forces support tribal resilience. Tribes with better courts and clearer codes tend to have more efficient governance and greater self-determination authority. Put another way, stable governance institutions that support stable business climates and local self-governance rules promote the rule of law.

One specific component of institutional quality stands out: self-governance authority under the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (ISDEAA). This 1975 law allows tribes to take over federal programs and run them locally. Under Title V of the act, tribes can compact with the federal government to redesign programs, consolidate funding streams, and manage operations with maximum flexibility. Instead of waiting for distant federal offices to administer programs, tribes with Title V compacts run health clinics, schools, social services, and other programs themselves.

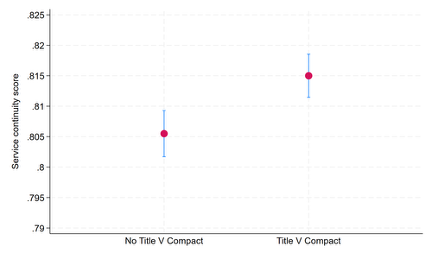

When tribal governments have clear authority and transparent processes, leaders can respond to crises by shifting funds, prioritizing essentials, and maintaining core operations despite federal constraints. Figure 2 shows the striking difference between those tribes with and without Title V autonomy.

Figure 2. Self-Governance and Service Continuity

Reservations with Title V self-governance compacts (right) maintained higher service continuity than those without (left). The dots show average continuity for each group; vertical lines show 95 percent confidence intervals. Title V tribes averaged 81.5 percent continuity, compared with 80.5 percent for non-Title V tribes, a 1 percentage point difference that is statistically significant (p = 0.0014). While both groups maintained most services, the self-governance authority provided a measurable advantage during the federal disruption.

These correlations do not mean higher institutional quality measured by REFI will eliminate federal dependency, for several reasons. Here are a few:

- Women, Infants, and Children nutrition programs: Despite tribal authority to administer these programs in some cases, federal processing delays affected nearly all reservations. When federal disbursement systems pause, local institutions can’t solve the problem.

- Previously awarded grants: Tribes could not draw down grant funds that had already been approved and allocated to them. This created artificial bottlenecks even for money Congress had already appropriated for specific tribal programs—requiring new federal approvals to access funds that agencies had already awarded.

- IHS administrative challenges: Even with advance appropriations protecting Indian Health Service budgets, the shutdown created administrative complications that affected some tribal health programs.

- BIA approvals frozen: Leases, rights of way, and land transactions requiring Bureau of Indian Affairs sign-off were frozen. No local institutional quality can override federal approval requirements when federal statutes mandate them.

What should Congress do?

The Senate Committee on Indian Affairs examined shutdown-driven disruptions at its October 29 hearing. Witnesses detailed impacts on nutrition programs, education, grant processing, and economic development. Analysts warned that current funding structures leave tribes unusually exposed, even though advance IHS appropriations helped many clinics avoid immediate closures.

There are three institutional changes that can make tribes even more resilient when the federal government shuts down.

- Extend advance appropriations beyond IHS clinics. Year-ahead funding for core tribal programs would provide the same protection IHS received. The IHS example shows why: advance appropriations insulated many clinics from immediate shutdown shocks. Congress should extend this logic. Lock in next year’s program budgets for education, nutrition, and other essential services so they continue even during shutdowns, insulating tribes from yearly budget spectacles.

- Create automatic continuity safeguards. When appropriations lapse, baseline nutrition benefits should continue flowing automatically. Tribes should retain access to already-awarded grants without needing new federal approvals. Pair this with automatic no-cost extensions and temporary waivers for minor procedural requirements. These safeguards don’t increase spending. Instead, they stop process failures from interrupting essential local governance.

- Streamline and scale ISDEAA contracting and compacting for willing tribes. The data show that tribes operating programs under Title V compacts maintained higher service continuity. Standard terms and faster timelines would let willing tribes run programs without spending months chasing approvals.

Some may worry that flexibility reduces federal oversight. The opposite tends to be true. Accountability improves when authority and responsibility sit in the same place. The alternative, accountability diffused across a faraway bureaucracy that is enduring furloughs, produces the opposite result.

Competent and capable

The evidence from the correlation between tribal resilience during the federal government shutdown and tribal economic freedom demonstrates a fundamental problem that has plagued tribes since there were relegated to reservations: the lack of tribal sovereignty. Since 1831, when the US Supreme Court declared tribes to be “domestic dependent nations,” tribes have had little ability for self-determination and self-governance. Then, under the General Allotment Act of 1877, nearly all reservation lands were placed under the trusteeship of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, forcing tribes to struggle to get the authority to manage their own affairs.

Tribal resilience during the recent government shutdown demonstrates once again that sovereignty and self-determination are keys to economic prosperity and freedom. This is not simply economic theory; it is the practical reality demonstrated during crisis. Governments work best when authority and responsibility sit close to the people affected. Tribes running their own programs adapted when the federal bureaucracy froze. Local leaders made hard choices about priorities when distant offices couldn’t respond. Self-governance did not eliminate federal dependency, but it certainly created space for tribal governments to act, and they did.

We did not have to wait for a record-breaking shutdown to recognize that Indian nations and their citizens are competent and capable. Their resilience in this recent time of crisis makes it clear that the time has come for real tribal sovereignty and self-determination.