No general statement about African demography is true. The variation in the continent is too great.

Africa today includes giant countries with populations near or exceeding 100 million (Egypt, Ethiopia, Nigeria) and tiny countries with populations under 1 million (Comoros, Djibouti, Cabo Verde, Reunion, Mayotte, Sao Tome and Principe, Seychelles). It includes countries where fertility is rising (Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia, Seychelles), countries where fertility is high but stable, falling by less than 1% per year (Mozambique, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, and ten others), and countries where fertility is high but falling very rapidly, 2.5% per year or more (Ethiopia, Rwanda, Kenya, Malawi, and Sierra Leone). It also includes countries where fertility rates are exceptionally high, exceeding six children per woman (Niger, Somalia, Chad, DRC, Mali) and countries where fertility has fallen to replacement levels (2.1) or below (Tunisia, Mauritius). Annual population growth rates for African countries range from under 0.5% per year (Mauritius, Central African Republic, Libya) to eight times that rate, or about 4% per year (Niger, Equatorial Guinea). Some African countries are highly urbanized, with urban populations around 60% of their total (South Africa, Angola, Botswana), while others are barely urbanized at all, with urban populations less than 20% (Burundi, Ethiopia, Malawi, Niger, Rwanda, Uganda). And while Africa has most of the world’s highly ethnically diverse countries, some African countries are quite low in ethnic diversity (Burundi, Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt).1

In short, Africa is enormously varied. About the only firm statement one can make is that Africa will be the most demographically dynamic continent in the world in this century. It will also be the source of virtually all labor force growth in the world, and by far the youngest region, in the 21st century. This paper will lay out the main aspects of Africa’s population dynamics in the coming decades, focusing on trends in mortality, fertility, population growth, labor force growth, and urbanization. I will discuss the reasons for Africa’s “demographic exceptionalism” and the main consequences of these trends for Africa’s and the world’s economy, politics, and security.

Mortality: Good News

Most of Africa has made remarkable progress in reducing mortality, especially in recent years, as improvements in nutrition, sanitation, and measures to combat malaria and other tropical diseases have led to substantial increases in lifespans. For Africa as a whole, life expectancy in the 1950s was less than 40 years, not much different from Europe in the 1700s. But by the 1980s, life expectancy surpassed 50 years, and by 2010–2015, had reached 60 years—a 50% increase. However, there is substantial regional variation; life expectancy in northern Africa is 71 years, led by Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco at 75 years, while in western Africa, life expectancy is just under 55 years, with Sierra Leone, Nigeria, and Cote d’Ivoire barely above 50.2

These gains in life expectancy are mainly due to dramatic declines in infant mortality. For Africa as a whole (and sub-Saharan Africa as well), infant mortality has fallen by 29% in just the last decade, from 2000–2005 to 2010–2015. Champions include Ethiopia (decline of 41%), Rwanda (51%), Congo (43%), and Botswana (46%). But all regions enjoyed declines of about 26–28%. Only a few countries suffering from high infant mortality had smaller declines: Burundi, Somalia, Central African Republic, Chad, Benin, and Mauritania.

Africa’s population today is thus far healthier and longer-lived than it was in the preceding century. The UN projects that by 2050–55, average lifespans in Africa (and sub-Saharan Africa) will reach 70 years, a dramatic convergence with other world regions.3

Fertility: A Conundrum

Based on the experience of other developing regions, these improvements in Africa’s mortality, especially infant mortality, would be expected to lead to similarly impressive reductions in fertility. In Asia and Latin America, fertility was similar to that in Africa in the 1950s, with about six children born per woman during her lifetime. Then with improvements in mortality and other indices of economic development, fertility steadily declined. By the late 1970s, total fertility had fallen to four, and then by the early 2000s to well below three. As of 2010–2015, fertility in Asia and Latin America is about at replacement levels, at 2.2 and 2.1 respectively. Yet in Africa, a wholly different pattern developed.

From the 1950s, fertility in Africa actually rose slightly, reaching nearly seven children per woman by the early 1970s. Fertility then sharply diverged in different regions. In northern and southern Africa, fertility began a steady decline. In northern Africa, fertility fell from seven children per woman in the 1960s to five by the late 1980s, and then to three by 2005–2010. In southern Africa, where fertility was six children per woman in the 1960s, the level fell to four in the late 1980s and down to 2.71 in 2005–2010. These regions thus followed the pattern of other developing regions, with about a one-decade delay.

By contrast, in eastern Africa in the late 1980s, fertility was still above seven children per woman. It then began a slow decline but still remains at nearly five in 2010––2015. In middle Africa, which had fertility of about six children per woman in the 1950s, fertility continued to rise all the way up through the late 1980s, reaching 6.76 in 1985––1990. Fertility then began to decline but very slowly, remaining at about six children per woman even twenty-five years later in 2010–2015. Western Africa was similar to middle Africa, with fertility rising and remaining close to seven children per woman up to the late 1980s, then falling slowly, but a bit further than in middle Africa, reaching 5.5 by 2010––2015. Western, middle, and eastern Africa have thus shown a dramatically different fertility path than other parts of Africa and other regions of the developing world. These are the only large regions of the world where, even after decades of falling mortality, fertility remains at or above five children per woman.4

Because these tropical regions dominate Africa in terms of population, overall fertility for sub-Saharan Africa remains at 5.1 children per woman in 2010–2015, and at 4.72 for Africa as a whole. Outside of Africa, except for a few small Pacific Island nations, and for the tribal Islamic countries of Yemen, Palestine, Afghanistan and Iraq, there are no other nations, much less regions, with a fertility of even 4.0. By contrast, thirty-two nations in Africa have fertility of 4.5 or higher, including giant countries like Nigeria (5.74) and Ethiopia (4.63), and extremely high fertility countries like Niger (7.4), Somalia (6.6), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (6.4), Chad (6.3) and Burundi (6.0).

As demographers Jean-Pierre Guengant and John F. May have observed, “This pattern of persisting high levels of fertility in the majority of African countries differs markedly from what has been observed in other developing countries since 1960.”5 Yet as population expert John Casterline recently observed, “there is nothing approaching consensus on the sources of this difference.”6

Why High African Fertility Persists

John Bongaarts, summing up the experience of most developing regions, notes that “As societies modernize, economic and social changes such as industrialization, urbanization, new occupational structure, and increased education lead first to lower mortality and subsequently to a decline in fertility.”7 The puzzle as to why these changes have not produced lower fertility in Africa, as they have done elsewhere, has given rise to two main answers: First, it is true that Africa has not yet experienced the same increases in education, income, and other indices of modernization that have been seen in Asia and Latin America. As Bongaarts notes, real income per capita in sub-Saharan Africa grew hardly at all from the 1970s to the 2010s, while real income in other developing regions rose sharply in these decades.8 Goujon, Lutz, and Samir have pointed out that many sub-Saharan countries had a “stall” in their progress in education that may have produced a “stall” in progress in reducing fertility.9 Thus it could be posited that Africa is simply behind in certain attainments and will eventually catch up to other regions.

Yet this is unsatisfactory for two reasons. First, northern and southern Africa did in fact follow the pattern of other regions, as would be expected; it is only eastern, middle, and western Africa that have not done so. Second, even for the latter regions, the rate and amount of their fertility decline is not comparable to what happened in other developing regions at similar levels of income and development. According to Bongaarts and Casterline, “… the median pace of change in sub-Saharan Africa (0.03 per year) is less than one-third the pace in the other regions [Asia and Latin America] (0.12 and 0.13, respectively).”10 Indeed, the behavior of fertility in sub-Saharan Africa is wholly at odds with the idea that economic progress determines the pace of fertility decline; as Bongaarts has shown, fertility rose when the region’s GDP/capita was relatively high in the 1970s, then began the onset of fertility decline in the early 1990s, when GDP/capita had fallen considerably, and then encountered a widespread stall in fertility decline in the 2000s, when GDP/capita had been rising more rapidly.11

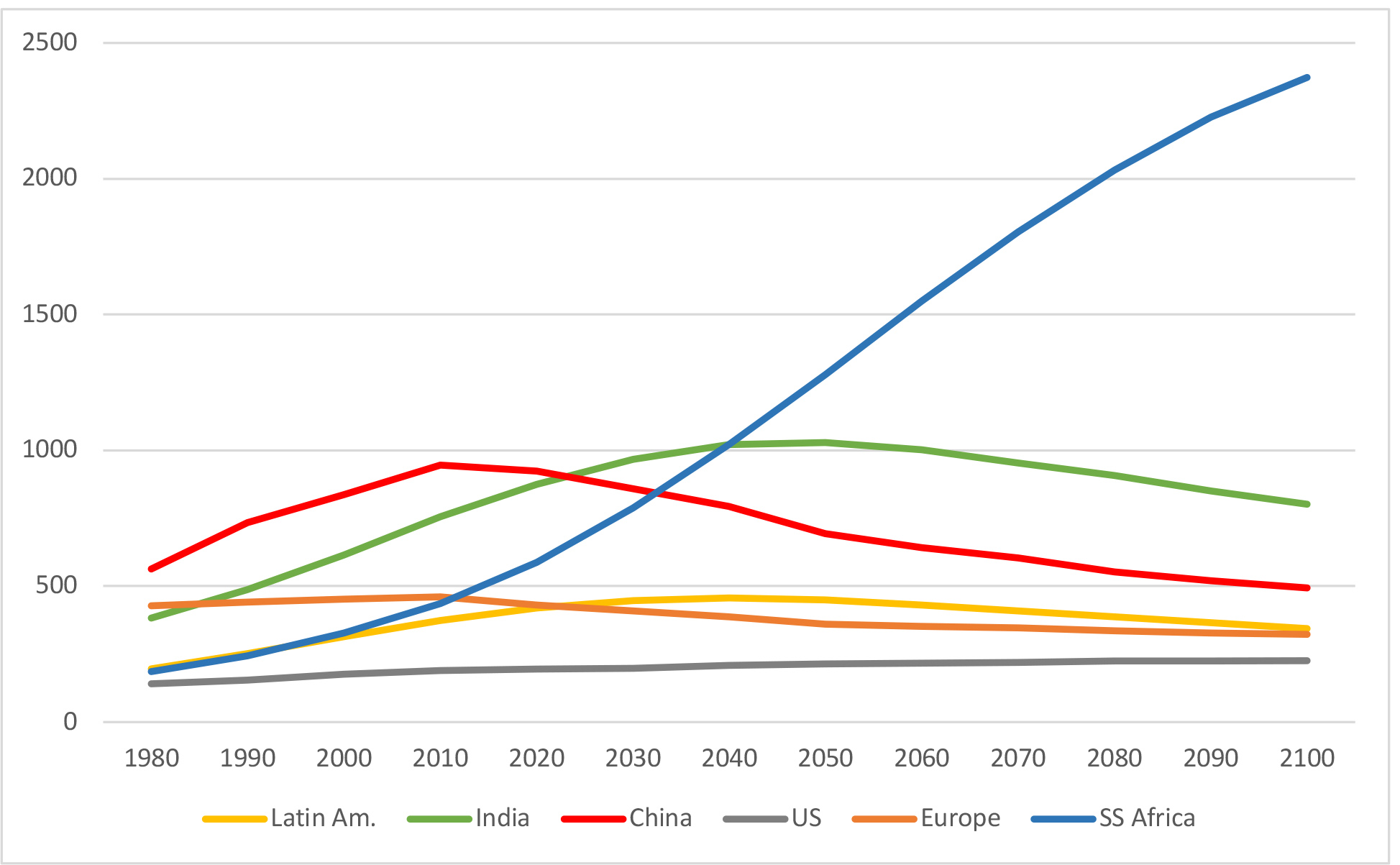

Forecasting of Africa’s demographic trajectory based on expectations that it would follow the pattern of other regions has thus been badly misleading. Figure 1 shows the difference between the decline in fertility from 1990–1995 to 2010–2015 projected by the United Nations Population Division in 1995 (shown in orange) and the actual decline in fertility as revealed by on-the-ground Demographic and Health Surveys two decades later (shown in grey).12 As can readily be seen, the UN fertility projections, based on analyzing the pattern of fertility decline in other developing regions, anticipated fertility reductions of .5 to 1 child per woman more than was actually observed.

As the slow fertility decline in Africa continues to confound expectations, the adjustments to population projections can be dramatic. Table 1 shows how the UN’s projections for Africa’s total population in various regions for 2050, as made in 2010, differ from their projections made in the 2017 revision, published in 2018. The differences—due to an expected decline in fertility that simply did not occur—are striking. By 2018, the new “medium variant” projection for the population of sub-Saharan Africa in 2050 is higher by 337 million people (15.4%) than the projection made just eight years before. For some regions, the new projections are almost thirty to forty percent higher than those of 2010. Indeed, the new 2018 “medium variant” forecasts are closer to the 2010 “high variant” forecasts, and sometimes exceed them. The new “high variants” have been similarly adjusted upwards. If, as has occurred to date, the “high variant” projections become the new “medium” projections, the forecast population for Africa in 2050 would be almost 2.8 billion, or 600 million more than the 2010 medium forecast of 2.2 billion. (See Figure 1)

Table 1. UN Population Projections For 2050 (Millions), 2010 vs. 2018

|

|

MEDIUM VARIANT PROJECTIONS |

HIGH VARIANT PROJECTIONS |

||||

|

2010 |

2018 |

Increase |

2010 |

2018 |

Increase |

|

|

AFRICA |

2191 |

2528 |

15.4% |

2470 |

2786 |

12.8% |

|

Eastern Africa |

780 |

888 |

13.8% |

879 |

982 |

11.7% |

|

Middle Africa |

278 |

384 |

38.1% |

314 |

420 |

33.8% |

|

Northern Africa |

322 |

360 |

11.8% |

368 |

399 |

8.4% |

|

Southern Africa |

67 |

86 |

28.4% |

79 |

97 |

22.8% |

|

Western Africa |

744 |

810 |

8.9% |

830 |

887 |

7.0% |

Because of the failure of Africa’s fertility to track the pattern of other regions, an alternative hypothesis has been advanced, arguing that Africa has an exceptionally pro-natalist culture that maintains high fertility even in the face of economic modernization. John and Pat Caldwell, who have led this line of argument, point to the exceptionally high desired family size that appears in African surveys.13 It has also been noted that in Africa, due to traditional taboos on post-partum intercourse and long breast-feeding periods, birth spacing was historically relatively high. This means that there is both less room to lower fertility by increasing birth spacing, and more room to increase fertility by reducing birth spacing if these traditional practices are relaxed.14

While this explanation would account for the low rate of fertility decline observed in Africa, and even the rise in fertility observed from the 1950s to the 1970s, it too has difficulties. In fact, we do observe a gradient in fertility within sub-Saharan Africa linked to modernization indices. Women in cities, and women having higher education and higher incomes generally have lower fertility than women in rural areas and with lower education and lower incomes.15 Modernization factors thus have an effect on fertility in Africa, just not quite in the same fashion as in other developing regions.

A more likely answer would be an interactive combination of modernization levels and cultural factors, such that certain regions of Africa—western, middle, and eastern Africa—have distinctive cultural patterns that affect the impact that economic development has on fertility. That is, as Bongaarts has argued, “the response of fertility to development could be fundamentally different in Africa than elsewhere in the developing world.”16

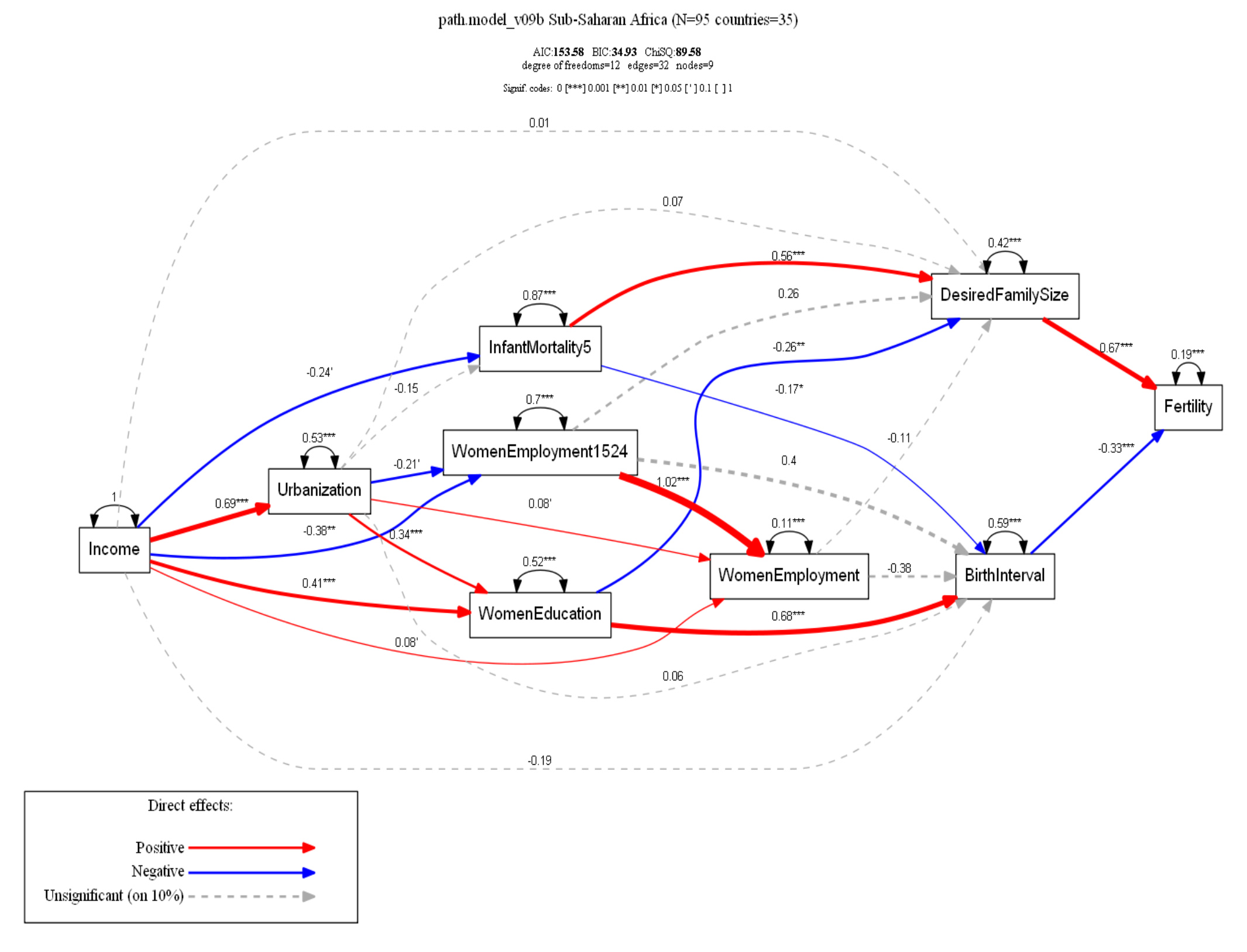

We test this hypothesis with a path analysis of how modernizing factors affect fertility in Africa vs. other developing regions.

Africa Is Different

John Bongaarts has found that while fertility in African countries generally declines in line with changes in income, education, mortality, and urbanization, in a multiple regression including all of these factors only education was consistently significant in driving fertility, contraceptive use and desired family size. In addition, he found an “Africa effect” such that for any level of development indicators, fertility was about one child per woman higher than in other developing countries. He thus concluded that both the level of economic development (especially education) and a distinctive pro-natal culture in sub-Saharan Africa contribute to Africa’s unique fertility dynamics. The finding that education was the most consistently significant factor supports the suggestion by Goujon, Lutz, and Samir that Africa’s “fertility stall” reflects a lack of progress in educational attainments.17

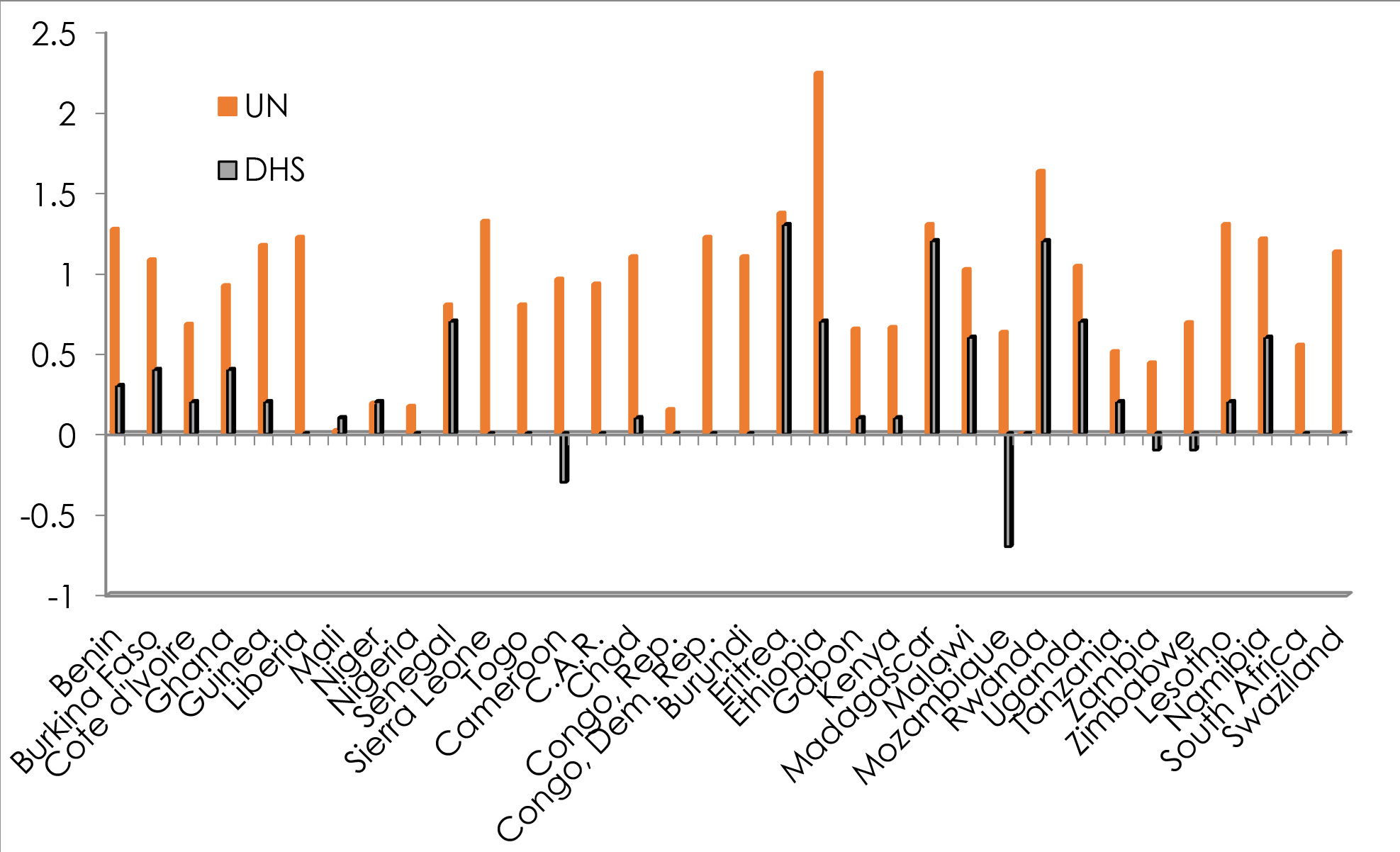

In Figure 2, I show a path model for the determinants of fertility in developing countries excluding sub-Saharan Africa. This is based on data available from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) for 31 countries at various time intervals from 1991 through 2013, making up 88 observations.18 The model follows the distinction made by Guegant and May between intermediate determinants of fertility, which are mainly socioeconomic conditions that influence fertility indirectly, and proximate determinants of fertility, which are mainly biological and behavioral and influence fertility directly.19 The intermediate determinants exert their influence on fertility through their effect on the proximate determinants. In the model, the intermediate determinants are income (real GDP/capita), urbanization (percent urban), infant mortality, women’s employment (both for young women age 15–24 and all women), and women’s education. The proximate determinants are desired family size and birth interval, which together shape total fertility.20

In the path model, positive effects are shown by red arrows, negative effects by blue ones, with the strength of the effect shown by the thickness of the arrow. Non-significant effects are shown as dotted arrows. In this model, fertility is affected most strongly by desired family size, though the effect of birth interval is also highly significant. The effects are almost all as one would expect from the development. (See Figure 2)

If we run the same path analysis on African countries, we would perhaps expect, following Bongaarts, that these relationships would still obtain but be weaker, or that, following Goujon, Lutz and Samir, that education would have a larger impact. The model using data from DHS surveys in 35 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, with 95 observations from 1991 through 2013, is shown in Figure 3. In fact, there are some surprising and marked differences. literature. Rising incomes lead to lower infant mortality, and have a direct effect on increasing birth intervals, thus reducing fertility. Rising income also leads to greater urbanization, which is associated with higher levels of women’s education and women’s employment (both for young women and all ages), and also has a direct effect on increasing birth intervals. Lower infant mortality leads to a reduction in desired family size, which greatly reduces fertility. In addition, lower infant mortality, women’s employment, and women’s education all also contribute to rising birth intervals; indeed these factors seem to impact fertility entirely through greater spacing of births rather than changes in desired family size. Still, the overall pattern is familiar—as incomes rise, urbanization and women’s education and employment rise as well, and all of these factors produce a decline in desired family size and increases in birth spacing, producing lower fertility. (See Figure 3)

Regarding similarities, in Africa rising income does lead to higher urbanization and to lower infant mortality, although the latter effect is much weaker in Africa. Lower infant mortality, in turn, has a somewhat stronger effect on reducing desired family size in Africa than in other developing countries but a much weaker effect on birth intervals. Higher urbanization is associated with higher women’s education and employment, in much the same magnitude of effect in Africa as in other developing regions.

However, there are huge differences in the results of women’s education and women’s employment. Outside of Africa, many factors contribute to larger birth intervals and hence to reduced fertility—Iower infant mortality, higher income, women’s education, young women’s employment, total women’s employment, and urbanization all have direct effects. The largest of those effects are through women’s employment, both for young women and total women. But in sub-Saharan Africa, the most powerful factor driving changes in the birth interval is women’s education. Women’s employment—whether for young women or for all women—has no significant impact at all! Moreover, in sub-Saharan Africa, but not other developing regions, women’s education also has a significant direct impact on desired family size. Also unusual is that in sub-Saharan Africa, unlike other developing regions, gains in income and urbanization have no direct effect on birth intervals at all; rather they act only indirectly through increasing women’s education.

In sum, Africa is different. In other developing regions, a cluster of modernizing changes work in tandem, reinforcing changes that stretch out birth intervals and thus reduce fertility. Most important is getting women into the workplace. Women’s education, however, has only a minor impact on birth intervals and none on desired family size. In sub-Saharan Africa, by contrast, women’s education is absolutely central, as it is the most important driver of changes in birth intervals and a strong direct factor in reducing desired family size. By contrast, women’s employment has no significant effect at all on fertility, not through family size nor through birth intervals.

How is this possible? In most developing countries, as women move into paid work outside the home—including young women with modest education—fertility is reduced as they have to choose between spending more time working and earning income and staying home to take care of their children. Women’s employment thus has a strong impact on fertility. However, in Africa, extended family child-care systems have developed that allow women to avoid this trade-off. The basic commitment enabling this pattern is the cultural expectation that aunts, uncles, siblings, grandparents, cousins, and even co-wives (where polygyny occurs) will take care of children while their mothers work. As Korotayev et al. note:

As long as extended families provide working women (not only agricultural workers, but ones in urban areas having paid employment as well) with relatives who are willing to come and assist with household tasks and child care, paid female employment may not only make a far smaller contribution to fertility decline in tropical Africa than that observed in other regions, but it may also actually delay fertility reduction in Africa by slowing the trend toward the nuclear family system.21

Korotayev et al. argue that the “right” to extended family childcare is rooted in longstanding cultural patterns distinct to tropical Africa. They note that this region (corresponding to eastern, middle, and western Africa) was characterized by hoe-based agriculture, in which women were the primary daily field workers, as opposed to the plow-based agriculture that prevailed in north Africa, Europe, and Asia. In the latter regions, men were the primary field workers, while women worked at textile and other domestic tasks that were undertaken inside the home and combined with child care. Tropical Africa thus commonly has extended families with widespread polygyny and large desired family size, all of which facilitate women working outside the home. When women shift to paid work outside the home this pattern simply continues and allows women to enter paid labor without worrying about child care.22 These cultural patterns buffer the effect of women’s employment on childbearing. Women’s employment thus should have no impact on birth spacing or fertility in tropical Africa, which is exactly what we find in the path model.

The factor that is central to fertility decline in Africa, more than any other, thus appears to be women’s education. It is only through their effects on this factor that other development changes seem to matter, as shown by both the path analysis in Figure 3 and Bongaart’s multiple regression showing that when total fertility, contraceptive prevalence, and desired family size are regressed on education, income, life expectancy and urbanization, only education is consistently significant. To understand future fertility in Africa, we thus need to take a closer look at its progress in education.

Africa’s Secondary Education Deficit

It is widely known that there are problems in the quality of education in developing nations. Teachers do not show up for classes, educational materials go missing, and effective testing, feedback, and cumulative growth in skills are often lacking.23 These problems are not unique to tropical Africa; they are found in many developing nations, especially in south Asia, where fertility has nonetheless declined. Yet in other nations, educational progress is far less important for fertility decline than in sub-Saharan Africa. As we have just seen, in most developing countries women’s education has a far smaller impact on fertility than women’s employment; only in sub-Saharan Africa is it the other way around.

This would suggest an opportunity for rapid fertility reduction in Africa by investing in women’s education. Yet Africa has, despite substantial increases in education in recent decades, apparently invested in the wrong kind of education for fertility reduction. That is, Africa has invested mainly in primary education, leaving a great deficit in secondary education. Moreover, such secondary education as is provided goes mainly to boys, with girls having a significant gap. Moreover, while provision of secondary education is weak across the board, with sixty percent of youth aged 15 to 17 in sub-Saharan Africa not in school in 2017, girls’ exclusion from higher secondary education is even worse, and particularly at lower income levels. For middle and low income females in sub-Saharan Africa, according to an assessment of DHS survey data in 2008, participation of female teens in secondary school was less than ten percent.24

For women, it appears that secondary education is the critical arena for reducing fertility. Women who leave school after primary education, which ends at age 12, are readily available for very early marriage and have no distinctive skills that allow them to be more productive or stand up to their husbands. Women who complete high school, by contrast, are unlikely to marry before age 18 and emerge with greater confidence and skills that allow them to shape their own fertility and make a greater economic contribution to their families.25

Moreover, as Véronique Hertrich has argued, women in Africa face particular difficulties in asserting their choices about their reproductive behavior. Women in Africa often are married while young to much older men or have to compete with co-wives in polygamous marriages. In either case, they are ill-placed to make demands about shaping family size. In addition, the extended family child-support system also carries with it pressure from the extended family to have a larger family size, since, in conditions of great uncertainty and rare opportunities, a larger family has valuable risk-spreading benefits for the entire extended family. The benefits of larger families, as well as the costs, are thus spread over a large extended family grouping, rather than the spousal couple.26 Completing secondary education makes it possible for young women to have the skills and confidence to assert themselves against these pressures and gain the ability to limit their childbearing if they choose to do so.

Demographer Joel Cohen has forcefully made the case for the effects of secondary education in high fertility societies. He writes:

Although there are other factors at work, in many developing countries, women who complete secondary school average at least one child fewer per lifetime than women who complete primary school only. In Niger in 1998, for example, women who completed secondary education had 31% fewer children (on average, 4.6 per lifetime) than those who completed only primary education (6.7). In Yemen in 1997, women who completed primary school had 4.6 children on average whereas women who completed secondary school had 3.1 children on average. In some sub-Saharan African societies, lifetime fertility is reduced only among girls who have had 10 or more years of schooling.27

However, despite its importance, the data on secondary school enrollments in tropical Africa tells a disappointing story. Overall, net secondary attendance for females in sub-Saharan Africa is only 34%; that is one-half the level in the Middle East and North Africa and one-quarter less than in South Asia.28 Table 2 provides a sample of primary and secondary enrollment rates for females in major countries of tropical Africa.29

As is clear, while considerable progress has been made in female primary education, there is a substantial gap when it comes to female’s secondary education. Even in countries where female primary attendance is over 80%, such as Tanzania, Burundi, Uganda, and Rwanda, female secondary attendance falls to 25% or less. Across all these countries, female enrollment ratios never reach even 50%.

To be sure, female education is not a necessary and sufficient condition for fertility decline. Kenya and Rwanda both have similar levels of fertility, 4.1 and 4.2 respectively, even though Kenya has almost twice the level of female secondary attendance. In Rwanda, a vigorous state-led campaign to promote contraception and legal limits on teenage marriage have had roughly the same effect as Kenya’s greater progress on female education. Yet on average, female education is the single most important factor in reducing fertility in tropical Africa. And tropical Africa severely lags other developing regions in providing women with secondary education.

In sum, the reason that tropical Africa continues to have extraordinarily high fertility is rooted in both this region’s distinctive extended family culture and its deep deficiency in secondary education. Unless the latter is addressed, we can expect that even continued growth in primary education, urbanization, and income per head will have only minor effects on reducing fertility. Given the rapid decline in mortality that Africa has enjoyed, and the still high fertility that it maintains, the future will be one of extremely rapid population growth.

Table 2. Africa’s Secondary Education Gap

|

|

Female Net Attendance Ratio |

|

|

|

Primary Education |

Secondary Education |

|

Niger |

46 |

13 |

|

Burkina Faso |

50 |

17 |

|

Nigeria |

66 |

49 |

|

Ethiopia |

67 |

18 |

|

Sudan |

67 |

45 |

|

Central African Rep. |

68 |

15 |

|

Angola |

76 |

17 |

|

Tanzania |

83 |

25 |

|

Burundi |

84 |

14 |

|

Dem. Rep. Congo |

85 |

41 |

|

Kenya |

87 |

44 |

|

Uganda |

87 |

21 |

|

Malawi |

95 |

34 |

|

Rwanda |

96 |

23 |

Growth Projections for Africa: 2050 and Beyond30

The combination of falling mortality and relatively stable and high fertility makes Africa unique among all world regions. Outside of Africa, the steady decline of fertility means that population growth will likely end in this century. The UN medium variant projection for developed countries shows their population peaking in 2054, and for less developed countries excluding the least developed countries (most of which are in sub-Saharan Africa), peak population is projected to be in 2077.

For Africa, however, with a total population of 1.2 billion in 2015, the medium projection is for population to reach 2.5 billion by 2050 and continue growing to 4.5 billion by 2100. Although fertility has fallen since its peak in the 1970s, the even greater decline in mortality since the 1980s means that population growth in Africa accelerated in the decades from 1980 to 2015. In the 1950s, before the onset of the demographic transition, Africa’s population was growing at 2.2% per year. But by the 1980s, this had increased by almost a third, to 2.8% per year. After the 1990s, growth rates declined very slightly to 2.7% for sub-Saharan Africa and a bit more, to under 2% per year, in northern Africa, where fertility declined more rapidly. But because of the growing demographic weight of sub-Saharan Africa, the growth rate for Africa as a whole remained at 2.6 % per year up through 2015 and is projected (again, the medium variant projection) to decline only slowly to 2.5% per year by 2020 and 2.4% by 2025 as fertility falls. While this decline is welcome, it must be remembered that even at an annual growth rate of 2.3%, total population doubles every 30 years.

Africa’s population would thus increase from 16% of the world’s population today to 26% by 1950, and 40% by 2100. This “medium variant” projection still presumes that fertility in sub-Saharan Africa will fall from an average of 5.1 today to 3.0 in 2050–55 and 2.2 in 2095–2100. If in fact fertility remains as high as 3.5 children per woman in 2050 and 2.65 in 2100, which is the UN “high variant” scenario, then Africa’s total population would soar to 2.8 billion by 2050 and 6.2 billion by 2100. In the following sections, we shall use the UN medium variant projections for future growth, but recall that this is a conservative, rather than “worse case,” scenario.

You may note that I have given population totals here for “Africa” and not just sub-Saharan Africa. This is because, although northern and southern Africa are distinct and have progressed further than other regions in their demographic transition to low fertility, they are still well above replacement fertility rates and hence experiencing significant growth. Moreover, over the last five years several countries in northern Africa—Tunisia, Algeria, and Egypt—have seen an unexpected increase in fertility of 8–12%. If this proves to be a sustained trend, rather than just a blip, it would contribute further to overall African growth.

Table 3 shows the countries in Africa where fertility is falling most rapidly (more than 10% in the last five years) and where it is stalled or rising. As can be seen, there is wide variation. However, fertility remains high in most cases, even in countries where fertility decline has been rapid. Moreover, as the left column shows, fertility decline is slow or absent in many countries where fertility is quite high, from 4.0 to above 6 or even 7 children per woman. Only very few countries have fertility declining at double-digit rates over this period. Thus, for Africa as a whole, fertility decline in the last five years was just 3.6%. Unless that decline significantly accelerates, Africa as a whole would not reach replacement fertility of 2.1 children per woman for 110 years, well into the next century.

The UN medium variant projection generally assumes that countries with higher fertility will shift to a more rapid decline in coming years. Thus, this variant assumes that Nigeria, whose fertility declined by 3% in the five years 2005–10 to 2010–15, will in the future experience a fertility decline of 6.6% every five years to 2050. That is certainly closer to the median for Africa as a whole. But given the wide variation among African countries, it is not clear why they should converge to a median rate of fertility decline.

Indeed, for Nigeria, whose population is divided between a higher-fertility and faster growing Muslim population in the north and a lower fertility and hence slower growing Christian population in the south, it may well be that fertility decline slows as the Muslim population becomes an ever-larger portion of Nigeria’s total population.

Table 3. Fertility rates in African countries with the highest and lowest rates of fertility change, 2005–2010 to 2010–2015, excluding small island states

|

LOWEST RATES OF FERTILITY DECLINE |

HIGHEST RATES OF FERTILITY DECLINE |

||||

|

|

Fertility in 2010–2015 |

% decline since |

|

Fertility in 2010–2015 |

% decline since 2005–10 |

|

Zimbabwe |

4.00 |

0.0% |

Malawi |

4.88 |

17.4% |

|

Namibia |

3.60 |

0.0% |

Rwanda |

4.20 |

15.5% |

|

Botswana |

2.88 |

0.9% |

Djibouti |

3.10 |

14.5% |

|

Libya |

2.40 |

1.3% |

Ethiopia |

4.63 |

13.6% |

|

Niger |

7.40 |

2.0% |

Swaziland |

3.30 |

13.6% |

|

Senegal |

5.00 |

2.0% |

Kenya |

4.10 |

13.4% |

|

Gambia |

5.62 |

2.5% |

Madagascar |

4.40 |

9.8% |

|

Congo |

4.86 |

2.9% |

Eritrea |

4.40 |

9.1% |

|

South Africa |

2.55 |

2.9% |

(All others decline is less than 9%) |

||

|

Nigeria |

5.74 |

3.0% |

|

|

|

|

Lesotho |

3.26 |

3.5% |

|

|

|

|

Dem R Congo |

6.40 |

3.6% |

|

|

|

|

Egypt |

2.93 |

-11.8% (increasing) |

|

|

|

|

Tunisia |

2.25 |

-10.1% |

|

|

|

|

Algeria |

2.96 |

-8.0% |

|

|

|

|

W Sahara |

2.60 |

-1.9% |

|

|

|

Africa’s unique high fertility regime will produce high rates of population growth in coming decades. Table 4 shows how the UN medium variant projections play out for the next two generations, to 2050 and 2100, for both Africa’s largest countries and for its fastest growing countries (there is some overlap between these two groups).

Nigeria, by these projections, will be more populous than the United States by 2050 and by 2100 have more people than all of Europe. By 2050, Ethiopia, Egypt, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Tanzania will each have larger populations than Russia.

It might be tempting to dismiss these numbers as simply fantastical. Could Niger go from 20 million to nearly 70 million by mid-century, or Angola to 76 million? Could Tanzania go to 300 million by 2100, or the DRC to nearly 400? But this is change projected over only two generations, or about 85 years. And it should be recalled that Africa is, historically, a vast and underpopulated continent. The population density of Angola and Somalia today is only 24 people per square kilometer; Tanzania is at 65, the Democratic Republic of the Congo is at 37. Even giant Nigeria has but 215 people per square kilometer. For comparison, India has 450 people per square kilometer, Haiti has 400, and Bangladesh has 1,278. So there is plenty of physical space for people; the question, which we return to below, is whether the economy will provide jobs and sustenance for such populations.

Table 4. UN population projections for Africa’s largest and fastest growing countries in millions

|

|

2015 |

2050 |

2100 |

|

AFRICA |

1194 |

2528 |

4468 |

|

SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA |

969 |

2168 |

4002 |

|

LARGEST COUNTRIES |

|||

|

Nigeria |

181 |

411 |

794 |

|

Ethiopia |

100 |

191 |

250 |

|

Egypt |

94 |

153 |

199 |

|

Dem R Congo |

76 |

197 |

379 |

|

South Africa |

55 |

73 |

76 |

|

Tanzania |

54 |

138 |

304 |

|

Kenya |

47 |

95 |

142 |

|

Uganda |

40 |

106 |

214 |

|

Algeria |

40 |

57 |

63 |

|

Sudan |

39 |

80 |

139 |

|

FASTEST GROWING COUNTRIES (Not Already Shown Above) |

|||

|

Niger |

20 |

68 |

192 |

|

Angola |

28 |

76 |

173 |

|

Somalia |

14 |

36 |

79 |

|

Zambia |

16 |

41 |

94 |

|

Burundi |

10 |

26 |

54 |

|

Mali |

17 |

44 |

83 |

|

Mozambique |

28 |

68 |

135 |

|

Burkina Faso |

18 |

43 |

82 |

|

Malawi |

18 |

42 |

76 |

To be sure, vigorous programs of state-led family planning, coupled with increased education, could bend these curves. If all of Africa were to accelerate its fertility decline to the rates achieved by Kenya, Rwanda and Ethiopia, of 13–15% per year, then Africa’s total population would only reach 3.1 billion instead of 4.5 billion by 2100.31 Yet the change to mid-century would be modest; the UN “low fertility” variant projection still forecasts an African population of 2.3 billion by 2050 (instead of 2.5 billion in the “medium variant”). This is because of “demographic momentum.”

That is, virtually all of the women who will be having children from now until 2030 have already been born, so that number cannot change. Given increasing health and lifespans, more of them than ever before can have children for longer periods, and more and more of those children will themselves survive to have children. This means that even considerable declines in fertility in the next few decades will not have a major effect on population growth until after 2050. For comparison, the country that had the most rapid decline in fertility in recent years has been Iran, where fertility fell from 6.5 children per woman to 2.0 in just twenty years, from 1980–85 to 2000–05. Nonetheless, Iran’s population increased from 38.7 million in 1980, when its rapid demographic transition began, to 80 million in 2010, when the transition was completed; such is the power of demographic momentum to keep population growing even when fertility is declining. Thus, it is almost impossible to expect Africa’s population to do any less than double by 2050, and that would be an optimistic projection. Rapid progress in reducing fertility could only have a major impact in the second half of this century.

Consequences of Rapid Population Growth: Economic, Political, and International

Social science has made great progress in understanding the implications of rapid population growth. We have learned that a significant number of social changes, including urbanization, political instability, education, and democratization are all linked to changes in population structure.32 We will look at how Africa’s rapid population growth will likely affect its labor force, its cities, its politics, and the international arena.

Labor Force Growth and the Economy

Other parts of the world also have growing populations, but that is mainly because their adult populations are healthier and living longer. Africa is unique not only in the speed of its population growth, but in the fact that this growth is driven by high fertility and falling infant mortality. This means that the additions to Africa’s total population are overwhelmingly young people.

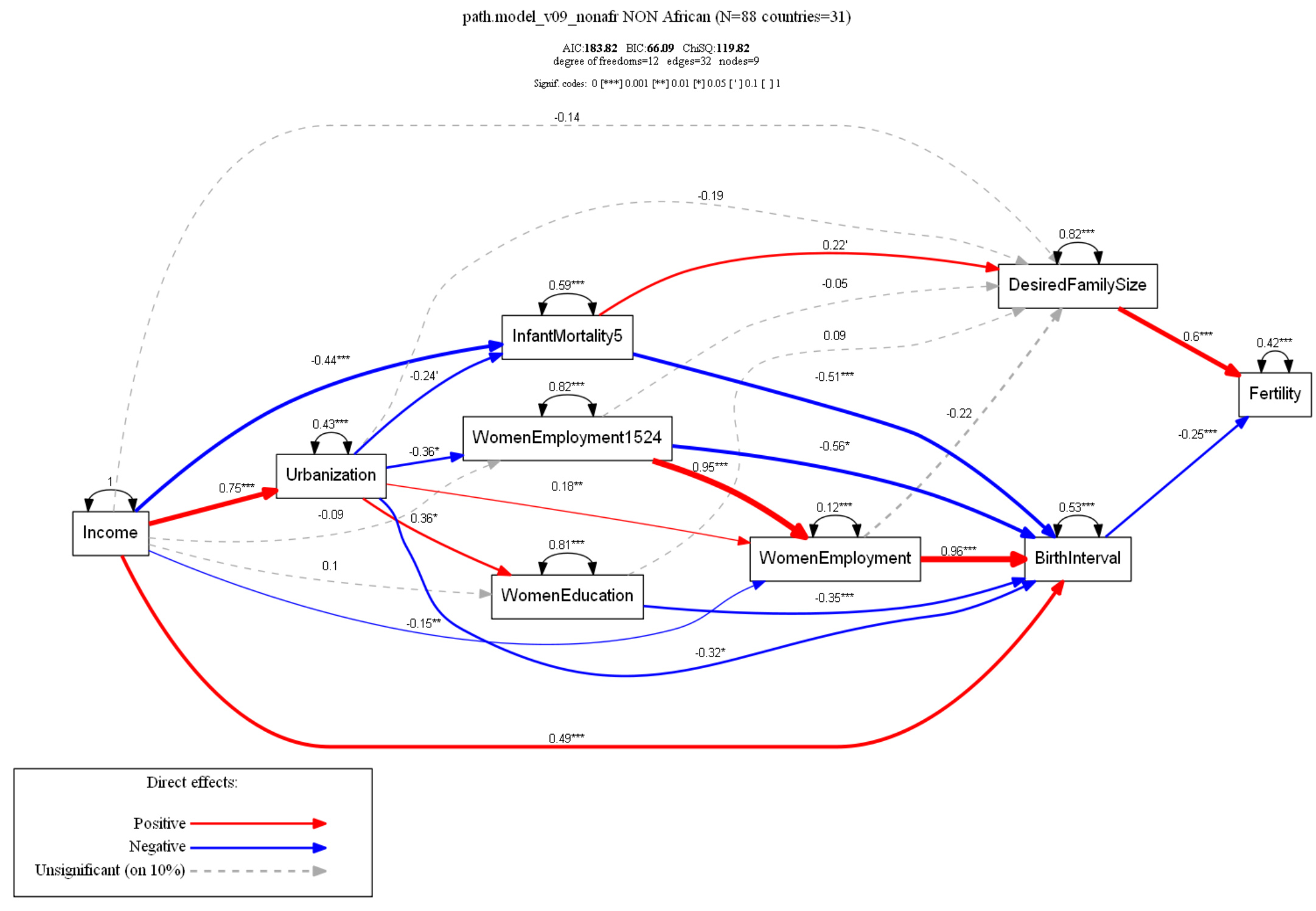

Africa will therefore have, by the second half of the century if not earlier, a surfeit of a commodity that is becoming increasingly rare in the rest of the world—young workers. Indeed, as shown in Figure 4, labor force growth (increase in the population age 15–59) in sub-Saharan Africa is far faster and greater in numbers than in any other region of the world, including China and India. After 2040, labor force age groups will be shrinking everywhere in the world, except in sub-Saharan Africa. By 2070, after thirty years in which all growth in the labor force in the world will be in sub-Saharan Africa, that region will have a working-age population of 1.8 billion, more than the United States, India, and China combined. If we focus on new entrants to the labor force, youth aged 15–24, by just 2040 sub-Saharan Africa will have well over twice the youth population of China, half again more than India, and almost three times the youth of the United States and Europe combined.33

Fundamental to the future of labor productivity in both Africa and the world will be the productivity of this massive increase in workers. As we have seen, secondary school enrollments in sub-Saharan Africa are poor. Although the numbers in Table 2 are for female enrollments, those for men are not much better. The high school completion rate among the male population up to age 21 is under 15% in Burundi, Niger, Madagascar, Burkino Faso, Mozambique, the Central African Republic, Gabon, Zimbabwe, Mali, Ethiopia, South Sudan, and Senegal. It is under 25% in, among others, Rwanda, Congo, Uganda, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. In South Africa and Kenya, who are among Africa’s leaders, it is 44%. (See Figure 4)

With an average across sub-Saharan Africa of a 31% high school completion rate for males, and 24% for females, the vast majority of African youth are unlikely to have the skills to compete with workers in south Asia or north Africa, nor to work with machinery. They are thus likely to be left to agriculture and the informal labor market, and low-productivity and low-income work—unless this changes.34

A fast-growing population and labor force could be a boon to the economy. Indeed, the countries of East Asia benefitted from a “demographic dividend” during their period of rapid population growth.35 But this only occurred after three conditions were met: (1) Fertility continued to decline so that the dependency ratio—the number of children to be supported by working adults—fell. With more of the population of working age, rather than being children, output per person rose sharply, savings increased for investment, and more could be invested in education and training for each child. (2) Investments were made to increase enrollments in secondary/vocational and tertiary education, reaching 100% for secondary/vocational enrollments. And (3) as populations moved from the countryside to the cities, they found work in factories and service firms, expanding the formal economy.

The “demographic window” for favorable development opens approximately when the population under age 15 falls below 30% of the total population, and the proportion of people 65 and older is still under 15%. Unfortunately, most tropical sub-Saharan African countries are far from this point, and with high fertility and falling infant mortality, they are not closing in on it. Almost all tropical African countries, including “good” performers like Kenya and Rwanda, are at 40 to 50% of their population aged 0–14.

Ideally, African countries would invest in secondary education—this would increase the skill level of workers and accelerate the decline in fertility. This would kick off a virtuous circle in which, as fertility fell, more money could be invested per student and worker, raising productivity further and leading to sustained and rapid economic growth. The alternative, if this is delayed, is a vicious cycle in which fertility continues to decline slowly or stall, spurring continued growth of the young population, making it harder to provide secondary education for all youth, and leaving less to invest in workers.

Africa has plenty of scope to increase its agricultural productivity and release workers for manufacturing and service jobs. Most of Africa’s farmland is not irrigated, and adoption of machinery, fertilizers, and improved species of plants and animals has just begun. Tropical parasites and diseases, which reduce human and animal productivity, are being conquered. A sorghum and cassava “revolution,” along the lines of the “green revolution” that transformed Asia, is potentially within reach.

The great difficulty is whether there will be jobs for those who move to the cities. To some degree, construction and service jobs grow in parallel with urbanization as expanding cities create their own demand. But if cities are overwhelmed with migrants, the construction of transport, housing, electricity, and sanitation lags behind, creating vast slums of substandard housing, rutted roads, and squatters. Happily, China is providing a good deal of investment in urban infrastructure in Africa, putting to use their knowledge of how to cope with fast growing megacities. Japan and other countries are investing as well. But it remains to be seen if this can keep up with the forecast urban growth.

For Africa as a whole, the urban population is projected to increase from 41% to 59% of total population between now and 2050.36 That means an increase in the urban population from 491 million in 2015 to 1.49 billion in 2050. Almost all population growth in the coming decades is thus expected to end up in cities. For example, in Nigeria, the urban population is expected to grow from 87 million to 287 million. But where will 200 million additional city-dwellers go? Will twenty million people be added to the population of each of Nigeria’s 10 largest cities in the next 35 years? Or will many dozens of new cities of 1 million or more arise from small towns? The Democratic Republic of the Congo is projected to have 100 million new urban residents by 2050, Egypt 85 million, Ethiopia and Tanzania 75 million. For comparison, China increased its urban population by 583 million in the thirty-five years from 1980 to 2015; that is only 58% of the increase in urban population that Africa is expected to add in the next thirty-five years.

In short, over the next few decades, Africa will add approximately one billion new workers to its labor force. Most of them will be young and eager for work, but unless things change radically, they will be poorly educated and poorly prepared for work. Almost all of them will be converging on cities, looking for a better life than they had in the countryside.

Some economists have worried that if robots and automation take over work in the developing world, there will not be the kind of low-wage manufacturing work for exports available for Africans that helped Asia move forward.37 Yet there are plenty of needs within Africa for African workers to address if the transport networks for intra-African trade were developed. Exports of agricultural goods are possible if Africa’s vast lands are more profitably used for high-value farming and animal husbandry; Kenya and Ethiopia are already among the world leaders in cut flowers, as well as high-value specialty tea and coffee. As we will discuss further below, Africa could also export workers to rich but aging countries who will need younger workers for landscaping, construction, and health and elderly care. Or they could trade on their climate to offer solar energy and follow Asia in developing resorts and retirement communities with lavish personal services for developed world retirees.

Sadly, these are likely to be only marginal developments. Absent truly unselfish and creative leadership, global investment, and drives to enlist labor in vast projects, Africa will be awash in under-employed youth converging on sprawling cities across the entire landscape.

Politics, Fragility, and Instability

Africa’s politics are famous for instability. Whether it is the hundreds of military coups that have taken place in African countries since independence, or the civil wars and genocides that swept across central, west Africa and Algeria in the 1990s and the multiple rebellions that have occurred in western Africa since 2000, the continent has been a byword for political instability. By 2010, there was some hope that Africa was turning a corner, and that states such as Tanzania, Botswana, Mozambique, Rwanda, South Africa, Ethiopia, Ghana, Uganda and Zambia were leading the continent toward more stable and democratic government.38 The uprisings in 2010–2011 in Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt were greeted with much hope as heralding an end to dictators and the spread of democracy. But by 2018, it had become clear that many of these states have joined the global trend toward the reassertion of strongman, autocratic rule. Only Ghana, Botswana, and perhaps Tunisia are maintaining their path to stable democracy. In Tanzania, President “Magufuli is fast transforming Tanzania from a flawed democracy into one of Africa’s more brutal dictatorships.”39 In Zambia, “the slide toward dictatorship was abrupt. Two and a half years ago, Zambia was one of Africa’s most stable democracies, a place so functional that it rarely made international headlines. Now it is ‘all, except in designation, a dictatorship,’ according to the country’s influential Conference of Catholic Bishops.”40 In Uganda, President Yoweri Museveni has held onto power for 32 years, changing the constitution as needed to remain in office indefinitely.41

Unfortunately, all these tragic trends could be forecast from the state of African demography. Numerous scholars have demonstrated that states with large youth bulges and sustained population growth suffer from a variety of political pressures.42 Whether it is the difficulties of providing jobs, affordable food, adequate housing, controlling inflation, or policing sprawling cities, governments are hard pressed to be responsive to the needs of rapidly growing populations, often falling into debt through the costs of subsidies and bloated government payrolls. Fights over resources among military or ethnic or regional factions are rendered more likely and more severe by the ready availability of young men to join factional struggles, as the young are both more drawn to ideological extremists and are more available for protest and rebellion, being less tied to jobs and responsibilities. Conflict, or the threat of conflict, promotes the seizure of power by autocratic leaders.

Demographers and political scientists have demonstrated that not only are relatively young societies more prone to political violence, rebellions, and civil wars, they are far more likely to backslide to dictatorship after venturing in the direction of democracy.43 As Leahy et al. have written, it is now clear that the impact of demographic conditions on a state’s “security, democracy, and development is significant and quantifiable.”44 They note that:

The finding that countries with very young populations are more vulnerable to conflict holds true despite the maturation of age structures globally at the end of the twentieth century. This suggests that the vulnerability of countries with a very young population was not merely a result of the large numbers of institutionally weak states in the early stages of industrialization. Although age structures in most countries in East Asia, the Caribbean and Latin America matured significantly over this three-decade period and many countries in these regions moved into more advanced age structures, the likelihood that countries with very young age structures would experience civil conflict actually increased in each decade from the 1970s to the 1990s.45

In fact, in these decades, countries in which 60% or more of the population was under 30 had more than four times a higher risk of experiencing outbreaks of violent civil conflict. That age structure still characterizes almost all of sub-Saharan Africa today.

Richard Cincotta has found that the chance of a country being a stable democracy exceeds 50% only once it has progressed in its demographic transition to the point where its median age is 29.5; the chances of being a stable democracy rise to 80% when median age reaches 35.46 With a few exceptions in northern and southern Africa, virtually all African countries have a median age below 25, and for many it is below 20. Indeed, the median age for Africa as a whole is just 19.4 years. Most African countries are thus decades away from reaching the age structures favorable to sustaining democratic rule.47

Aside from the small island states of Mauritius, Reunion, and the Seychelles (median age 35), as of 2015 no countries in Africa except for Tunisia (31) had reached a median age of 30. Several states in northern Africa—Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco—along with South Africa, Botswana, Cabo Verde, and Djibouti, with median age around 23–25, are on track to reach the 50% threshold in the next decade. But for all other African states, with median age of 22 or less, the probability of achieving stable democracy is 10–20%. This does not mean that none of these states will become democratic; but it does mean that for the next two decades, it is most likely that some 80–90% of African states will remain, or revert back to, autocracies, with recurrent waves of violent conflict.48

If there is a region to look at as a likely model for Africa’s future, one need look no further than the Middle East and North Africa. Even if sub-Saharan Africa’s economies prosper, that is not likely to resolve the problems of political disorder. The countries of the Middle East and North Africa, after rapid population growth and then progress in their demographic transition, enjoyed decades of economic growth and rapid educational expansion prior to the outburst of revolutions in 2010–2011. Yet they also exhibited a huge increase in youth population and urbanization, severely unequal distribution of the benefits of growth, high degrees of corruption and political exclusion, and struggled to keep up with prior commitments to subsidize food prices, fuel, and government employment. Syria also was affected by climate change, as a severe drought disrupted rural areas and spurred urban migration.

Many of the countries of tropical Africa are likely to follow this path in regard to both economic growth and educational progress, combined with not enough jobs, strained governments, corruption, autocracy, and extreme climate events. That was a formula that led to revolutions and civil wars in the Middle East and North Africa and will likely do the same in tropical Africa in the coming decades.

Africa and the International System

Until very recently, Africa was simply too small, in terms of its population and its economy, to matter much to the world. In 1950, the total population of sub-Saharan Africa was 180 million people. That was only twice the population of Japan, and only about one-third the population of Europe. Africa was a largely empty continent, useful mainly as a source of raw materials and notable primarily as an arena for imperialist competition among European powers. In the 1960s, imperialism was thrown off and most African countries gained their independence, but Africa’s role as mainly a source of raw materials remained. As late as 1980, sub-Saharan Africa had just 372 million people, and Africa as a whole had 480 million; at this time Asia had 2.6 billion people. Europe still had almost twice the population of sub-Saharan Africa.

This has now changed with remarkable speed. As of 2015, sub-Saharan Africa’s population, at 970 million, is now one-third larger than that of Europe. By 2040, twenty-five years from now, sub-Saharan Africa is projected (again, by the UN medium variant) to have 1.8 billion people, making it more than twice as populous as all of Europe (including Russia). In the sixty years from 1980 to 2040, tropical Africa will have gone from having half the population of Europe to having twice its population.49

Nonetheless, Africa’s economy remains quite small, due to the deep poverty of its population. As of 2018, according to the IMF, the total gross domestic product of all of Africa in current U.S. dollars is $2.3 trillion—just 50% more than the GDP of Australia and New Zealand. That is about one-tenth the GDP of East Asia or of Europe and under three percent of total global output. In short, the total economic output of Africa is not much more than a rounding error in the global economy.50

That is not likely to change anytime soon. If the global economy grows at 3% per year, and Africa’s economy were to grow consistently at 5% per year, it would take 70 years for Africa to be generating even 10% of global economic output; even though by that time Africa would likely have over one-third of the world’s population. While Africa will have a vast number of potential consumers, their actual purchasing power will be modest. Africa will likely remain, overall, an economic pygmy among giants.

Of course, inequality means there will still be a substantial middle class. With a population of 2.5 billion by 2050, the richest ten percent would comprise 250 million people with a middle class to upper class income, concentrated in some 20-30 metropolitan areas scattered across the continent. This will mean a substantially increased demand, perhaps four or five-fold, for air travel, tourism, and consumer goods compared to today’s level. Yet this market will still be of little interest to global multi-nationals. Much like China, Africa will likely disappoint as a consumer market, due to low per-capita incomes, distinctive local tastes, a large informal market, and high rates of savings to cope with an uncertain environment.51

The impact of Africa on the international system will thus depend mainly on the impact of its vast population growth. This will matter mainly in terms of regional instability, extremism, climate change and disease, and international migration.

We have already noted that Africa is likely to remain a continent of politically fragile states, mainly autocracies with chronic violence. As the world’s largest pool of youth aged 15–24, it is also likely to be an incubator and recruiting ground for all kinds of extremist ideologies. It will be a major concern for developed regions to contain the spread of violence and extremism from Africa, just as in recent decades it has been a concern to contain the spread of these tendencies from North Africa and the Middle East. At present there are already violent extremist movements active in Nigeria (Boko Haram), Somalia (al-Shabab), Uganda (Lord’s Resistance Army), Mali (Al Qaeda in the Islamic Magreb), and elsewhere. This problem is likely to grow worse as Africa’s youth population grows in the context of inequality and corrupt autocratic regimes.

Africa is also potentially a source of international risks in regard to climate change and disease. The latter risks were brought home with the outbreak of Ebola in the United States in 2014. In the coming decades, the number of travelers from sub-Saharan Africa to other continents, driven by increased population and higher incomes in Africa, is likely to increase by three or four times.

In regard to climate change, much of the world’s fate depends on what happens in Africa. At present, due to its poverty and mainly rural population, Africa is a trivial generator of greenhouse gases. In 2016, Africa as a whole emitted 1.33 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, less than Russia by itself. 80% of that comes from just six fossil fuel dependent industrializing countries: South Africa, Algeria, Nigeria, Libya, Egypt and Morocco. Africa’s CO2 output per person is thus a mere 1.1 tons per year. That compares with 1.8 tons per year in India.52

But Africa’s CO2 output per person has been growing fast, much faster than its population. That is to be expected, as increases in income and urbanization will lead to higher per capita fuel and electric consumption. From 1950 to 2016, Africa’s CO2 emissions increased by a factor of 14.53 Today, Africa has 1.2 billion people and is projected to have 3 billion by 2060. If CO2 emissions per capita by that date were merely to rise to the level of India today, Africa’s total CO2 output would quadruple to 5.45 million mt of CO2 per year—the same total as the United States today. Put another way, if by 2060 Africa achieves the same emissions level per person as India today, then even if China, the United States, India, Russia, Japan, and Germany were ALL to cut their CO2 emissions by 20%, that would not offset the increases to CO2 output from Africa.

It is thus vital that Africa be put on a course of solar, wind, geothermal, hydro, and nuclear power for its fuel needs. Otherwise, even a modest increase in Africa’s per capita emissions will make it impossible for more developed countries to make meaningful reductions in the world’s carbon loading. Fortunately, Africa has plentiful wind, hydro, uranium, and solar resources. Unfortunately, with the backing of foreign capital, mainly from China, over 100 coal-powered electric plants are in various stages of planning or development in Africa.54

Next to climate change, the largest impact that Africa is likely to have on the international system is through a growing contribution to international migration. This will have two components: labor migration and refugee movements.

To date, sub-Saharan Africa has been a modest contributor to global labor migration. North Africa has had a much higher rate of migration outside of Africa, with many north Africans working in the Gulf oil countries and, more recently, refugees from the Libyan civil war seeking asylum in Europe. Still, the number of sub-Saharan Africans seeking to move to the United States and Europe has been steadily rising. From 2010 to 2017, Europe received nearly one million asylum applications from sub-Saharan Africans who reached its shores, more than half of them in the three years 2015–2017; the United States received fewer, about 400,000 from 2010 to 2016. But many of these claims were rejected; the net increase in sub-Saharan Africans living in Europe in these years was only 420,000. In the United States, which took more students and skilled workers, the increase was 325,000 in the same period. Altogether, there are an estimated 4.15 million sub-Saharan Africans living in Europe in 2017 and 1.55 million in the United States55

Of these international migrants, about half of those living in the United States are from four countries: Nigeria, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Kenya. In Europe, there is a greater mix, with half of sub-Saharan migrants coming from Nigeria, South Africa, Somalia, Senegal, Ghana, Angola, Kenya, the DRC, and Cameroon. What are the prospects for a major increase in migration from these and other countries?

The push factors are obvious: the number of young Africans aged 15–24 is growing rapidly; their numbers will double from 230 million in 2015 to 461 million by 2050 (94% of that increase coming from sub-Saharan Africa). Many will be un- or under-employed at home. More and more of them will learn about life in Europe and the United States from friends, relatives, and media and have the resources to consider moving. While most will simply move to larger cities in their own country or to other countries in Africa or the Middle East, most who are surveyed say that their first choice of destinations is Europe or the United States But even if the number of migrants from sub-Saharan Africa to the United States and Europe were to double, or even triple, in the next three decades, the annual numbers would be less than 600,000 per year to Europe (out of a projected population of Western Europe in 2050 of 457 million, or 0.13 percent), and less than half that to the United States (or about 0.08 percent). If done in an orderly way, this volume of migration is not a threat.

One may worry that a bigger risk is a repeat of what happened in 2015 with the surge of immigrants to Europe driven by Syria’s civil war, when one million migrants entered Europe in the span of a few months, briefly pushing migrant flows up to five times higher than in previous years, creating a shock to Europe’s political system. Syria’s war created roughly five million international refugees out of a prewar population of 21 million. If, say in 2025 a combination of climate disaster and civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo (estimated population then of 104 million) or Ethiopia (126 million) or South Africa (62 million) broke out, might it also send millions of refugees streaming toward Europe? That is possible; if assistance cannot be given in place, or if refugees are not welcomed in neighboring countries, those desperate for survival might undertake the costs and risks of trying to get to Europe. The Syrian surge turned out not to have been a great economic burden for Europe but had immense political consequences. The sudden flow of foreigners to Europe’s borders raised fears of loss of identity and control among Europeans and promoted authoritarian governance.56 If roughly every decade a major crisis were to send 500,000 to one million African refugees to Europe’s borders, that could have the effect of periodically exacerbating identity crises and political extremism, reinforcing populist regimes, and doing sustained damage to European democracy.

A different and more pragmatic approach to migration would be to view the vast numbers of young workers in Africa as an untapped resource. For most resources, whether it be minerals or fossil fuels, if they are rare in Europe but cheap and plentiful elsewhere, international investment flows in to refine and upgrade the resource and export it to Europe. Why shouldn’t African labor be viewed similarly?

Europe and America are already facing severe shortages of low-wage labor for service, construction, and eldercare jobs—work that is not easily or cheaply done by robots. There are also shortages of skilled workers for jobs such as nursing and pharmacy and healthcare, shortages that will grow as the populations of Europe and America age.

Europe and America also are facing huge future costs of funding their national and local pension and health care systems with a shrinking labor force. In the United States, for example, the recent fall in fertility to record low levels has resulted in the U.S. Census reducing its population forecast for 2050 from 439 million (forecast in 2008) to 390 million (latest forecast in 2017).57 That means in 2050, the United States will have almost 50 million fewer people—most of them prime working age—than was expected just ten years ago to pay into social security and Medicare to support seniors; and that is with recent immigration rates of one million per year being sustained to 2050. Without immigration, due to low fertility, the U.S. labor force would already be in decline. The United States will need an additional one million immigrants per year for the next 35 years just to get back to the 2050 population that was expected a decade ago!

Many potential African migrants to the United States and Europe are Christians who speak French or English, mitigating anxieties about how they would “fit” into American or European society. It would therefore make sense for the United States and Europe to plan on attracting more migrants from Africa to meet the needs of their aging and shrinking native populations. This could be combined with training and pre-screening overseas to create orderly migration inflows. Increased training and migration of Africans to developed Western countries could also, as happened with India and China, create a virtuous circle of return migration over time to increase managerial and entrepreneurial skills in Africa, improving prospects for African countries’ development.

Policy Recommendations: Meeting the Challenges of Africa’s Demographic Growth

Ideally, Africa’s population growth, and the entry of African populations into the global economy as workers and consumers, would recapitulate the success stories of Eastern Asia. Even Bangladesh, once written off as a basket case, and whose own population doubled in the 30 years from 1975 to 2005, has emerged as a success, being one of the world’s fastest growing economies and raising its per capita income by 64% in the decade from 2007 to 2017.58 But Bangladesh’s performance depended on reducing its fertility from 6.9 children per woman in 1970–75 to 2.5 in 2005–10, and making investments in its human capital and infrastructure that allowed it to become a major textile manufacturer and exporter and create its own financial, steel, pharmaceuticals, and food processing industries.

To emulate that success, African countries and their Western supporters and partners need to adopt a two-pronged approach. From now until 2050, the major goals must be coping with the consequences of unavoidably rapid population growth and yet still working to lower fertility as quickly as possible so that after 2050 Africa can achieve sustained high growth in income per head. During the 30 years from 1975 to 2005 when its population doubled, Bangladesh had only modest growth in per capita income and struggled with coups and unstable government. Yet it managed to reduce its fertility and improve its education and economic infrastructure so that it was poised for rapid growth in the following decade.

For Africa to achieve similar fertility reductions in the next 30 years will be difficult. As Hertrich has explained, changing Africa’s high fertility will require changing the conditions that both lead to higher desired family sizes and weaken women’s ability to assert their preferences if they desire fewer children.59 That means empowering women through later marriage and greater education. Indeed, probably the single most important investment for international donors that can be made in Africa’s future—both for the earning capacity of its population and stemming the flood of population growth after 2050—is to target universal secondary education for both sexes.

If by 2050 Africa can turn the corner on fertility and reduce its population growth, and make the investments in its human capital and infrastructure needed to lay the foundation for future growth, then in the second half of this century Africa could be the main motor of global economic growth, much as China has been for the last thirty years and India could be for the next thirty. Yet if Africa fails to do so, the ever-larger swelling of its population will mean that its economic lags and political instability will only increase and become an even greater burden for the international system later in the century.

The pressures on Africa’s labor markets, urban centers, and political stability from the population growth that will inevitably occur by mid-century will be immense. African countries and developing nations would be wise to plan now to meet these pressures by developing a variety of stand-by quick response institutions. This would include provision of humanitarian aid for larger populations likely to be affected by extreme climate events and provision of peace-keeping and refugee settlement and support for populations likely to be affected by rebellions and civil wars. It would also include provision of social media campaigns, information sharing, and well-trained police/gendarme forces to combat the spread of extremist ideologies and extremist actors.

While it would be too much to expect most sub-Saharan African countries to achieve stable democracy before their fertility is brought down and the age structure of their societies matures, critical steps can be taken by the international community to discourage corruption, improve administrative and legislative capacity, and raise expectations regarding government behavior. Africa would likely make greater progress under regimes, whether autocratic or democratic, that respect the rule of law, develop strong private sectors, and invest in education and infrastructure than under regimes, whether autocratic or democratic, that are highly unstable, corrupt, ineffective, and invest mainly in show-projects and elite consumption.

There is also great potential for Western countries to help themselves, as well as Africa, by treating the surge of young people in Africa as an opportunity rather than a threat. By helping to train African workers in their countries and facilitating a greater but more orderly flow of migrants, Western countries can help meet their own shortages of labor, take better care of providing for their aging populations in terms of both fiscal health and physical care, and create cadres of African workers who will be capable of contributing to the world economy.

Indeed, among the literally billions of Africans who will be born in the 21st century, there are no doubt future Mozarts, Einsteins, Salks, and Picassos, as well as brilliant performers, writers, and thinkers of all kinds. To deprive the world of that talent by lack of education and opportunity would be a tragedy for all of mankind.

In the coming decades, Africa will have by far the fastest growing population anywhere in the world and will soon be the only fast-growing source of one of the most precious resources on the planet—young people. This will create risks and anxieties, tempting the developed world to try to wall itself off from Africa. Yet that would be a tragic mistake. Helping Africa to develop those youth as productive contributors to their own and the global economy, and managing Africa’s future energy transition to minimize its impact on climate, will be the vital tasks for global security and prosperity in the coming century.

Jack Goldstone is the Virginia E. and John T. Hazel, Jr. chair professor of public policy at George Mason University and a global fellow of the Woodrow Wilson International Center.

Supporting Data

Figure 1. UN Projections of Fertility Decline from 1990–1995 to 2010–2015 vs. DHS Reported Fertility Decline

Figure 2. Path Model for Fertility in Non-African Developing Countries

Figure 3. Path Model for Fertility in Sub-Saharan African Countries

Figure 4. Growth of Labor Force (Population age 15-59) in millions, 1980–2100