- Education

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

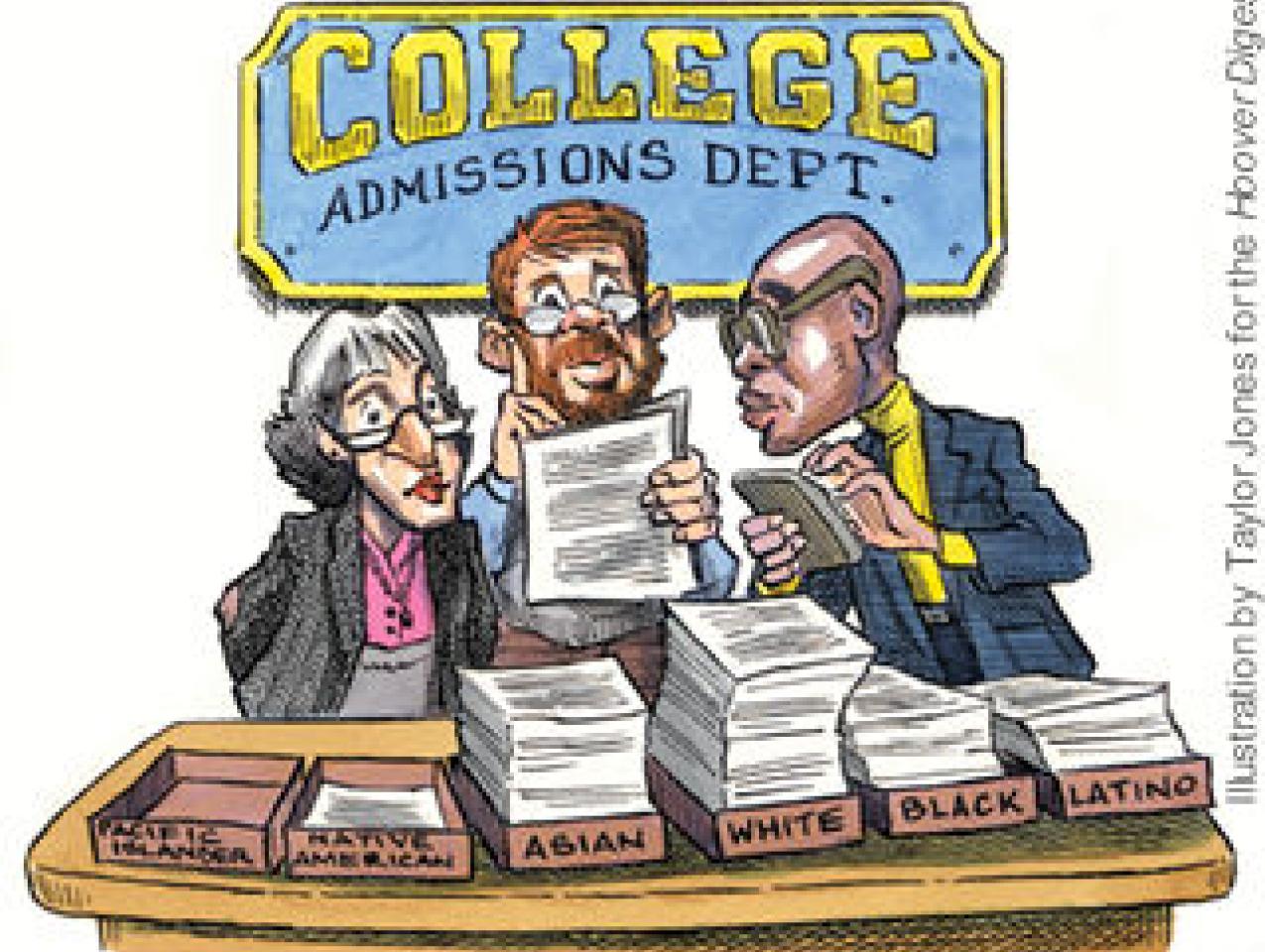

On all the key issues, race preferences won the day. Rendered academic were 25 years of disputes among legal scholars and the circuit courts as to whether Justice Lewis Powell’s cryptic ruling in the landmark 1978 Bakke case, joined by none of his brethren, was binding precedent. Erased were Powell’s creative ambiguities. Where Powell had suggested a state school’s right to employ the competitive consideration of race and ethnic origin, in assessing the University of Michigan Law School admissions procedures, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor decreed that student body diversity is a compelling state interest that can justify the use of race in university admissions. And where Powell had left for another day the question of how preferences must be narrowly tailored to achieve their purpose, Justice O’Connor gave Michigan its desired right to accept a critical mass of blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans—an approach that had functioned as a soft quota system since its first application in 1993, always producing between 10 and 17 percent underrepresented minority students per class.

The 6-3 Supreme Court decision in the companion Gratz v. Bollinger case rejected Michigan’s rigid undergraduate admissions system, in which favored minority applicants automatically received a 20-point bonus on a 150-point admissions scale, a foot on the scale heavy enough to accommodate nearly every minority candidate unlikely to flunk out. Coupled with approval of the critical mass formula in Grutter, the two decisions provide far less of a check on naked race preferences and more of a roadmap for universities negotiating the tricky preference terrain and arriving at the desired destination safely under judicial protection. Admissions committees all across the thickly populated race preference landscape are already discovering the virtues of a critical mass, just as their predecessors discovered the joys of diversity after Bakke.

The Grutter decision took the anti-preference political community by surprise. It had begun to get used to the taste of victory. As the era of de jure discrimination receded, there were fewer instances when specific discriminatory practices of that era could be used to justify remedial preferences. Beginning with the 1989 Croson case, the Supreme Court had invalidated racial or ethnic considerations in state and federal contracting and in the drawing of congressional district lines. Voters in California and Washington State had by ballot initiative rejected preferences. In Florida, a similar policy was implemented by executive order. In Texas, the federal circuit court rejection of preferences at the University of Texas Law School had led to legislative enactment of what purported to be a race-neutral undergraduate admissions system.

Representatives of groups such as the Center for Individual Rights were thus looking for the right case to serve as a test for the preference issue, hoping to defeat race preferences once and for all. The University of Michigan seemed the ideal choice.

Background

Michigan Law School policies can be traced back to a three-year period in the mid-1960s when, with admissions determined almost entirely by academic credentials, not a single black applicant qualified for admission to the law school. As recounted by Professor Terrance Sandalow in a 1998–99 Michigan Law Review article, a horrified faculty instructed its admission officer to begin accepting black students who appeared likely to do well enough to graduate. This effort evolved into the school’s special admissions program, whose stated goal was to admit 10–12 percent of each class from an underrepresented minority category consisting of African Americans, Mexican Americans, and Native Americans. In 1992 the law faculty unanimously adopted an admissions policy document that, while recognizing the predictive relevance of the LSAT and past academic performance, also required the continuing admission of what it called a critical mass of preferred minorities who seemed likely to do well enough to graduate with no serious academic problems. Over a five-year period analyzed for trial, the record showed widely disparate admissions treatment of preferred minorities relative to white or Asian American students with similar grades and LSAT scores. In some cases the minority applicants were hundreds of times more likely to win admission.

The admissions policies—both graduate and undergraduate—were only part of the political correctness upheaval that infected Michigan and many other elite institutions in the 1980s and 1990s. Under the so-called Michigan Mandate proclaimed by President James Duderstadt in 1987, multicultural awareness became the catchphrase and dozens of diversity programs were imposed on the academic regime; speech codes were written (and ruled unconstitutional by the courts); the races adopted segregated housing; and at least one faculty member was harassed out of the classroom by the PC minions (he was later dropped from the roster of required course teachers). Eventually, even graduation ceremonies took on a flavor of apartheid as blacks held their own celebrations, receiving kente cloths along with their mock diplomas.

Like many universities that practice on the outer edges of affirmative action, Michigan was none too anxious to share its data. When philosophy professor Carl Cohen, a university scholar since the 1950s and longtime foe of race preferences, sought basic admissions information in the mid-1990s, the university complied with many of his requests only after he invoked the Freedom of Information Act. To this day, those seeking information on the class standing of preferred minorities are told no such records are kept. In interviews, university officials seek to lessen the impact of race preferences by insisting that whites from rural or impoverished urban areas also win points toward admission, but they are pitifully short of data to back up that claim.

The Legal (and Political) Battle

In choosing Michigan to make their stand, opponents of preferences ran into Duderstadt’s successor, Lee Bollinger, a tough and sophisticated aca-demician who had both the commitment and the resources to build a very formidable case. Bollinger, a former law clerk to Chief Justice Warren Burger, had been dean of the law school during the heyday of the Michigan Mandate, where he and members of his faculty had advised the code drafters and—until the court challenge was filed—watched in silence as students were prosecuted for such offenses as arguing that certain intellectual capabilities are sex-linked or noting that black dental students had experienced difficulty with one particular course. Bollinger brought to the table a wise appreciation for the importance of establishment support in a case with broad implications for society and also for building a record to support a potentially sympathetic justice searching for ways to distinguish what Michigan was doing from the quotas held illegal in Bakke. He and a core of able staff and faculty lawyers, along with two mighty Washington law firms, set about building that record. University sociologist Patricia Gurin published a study purporting to show the compelling need for a diverse campus. William G. Bowen and Derek Bok, authors of The Shape of the River, the deeply flawed defense of race preferences, offered themselves as witnesses for the university.

Michigan’s lawyers orchestrated a wonderful assortment of amici curiae briefs representing the core of industrial, professional, and even military power in the nation: Ford, General Motors, the American Bar Association, the American Council on Education, the New York Yankees, and dozens of others. The common theme was that in a diverse global environment the United States cannot compete without being able to draw on the talents of representatives of all races and ethnic groups trained at elite institutions. They argued further that the domestic order will not be stable unless minorities are able to participate fully, particularly in those institutions associated with wealth, status, and power. Indeed participation in certain institutions is viewed by minority groups as evidence of the legitimacy of the institutions themselves. This point was driven home most forcefully in the so-called Green Brief submitted by an ad hoc group of prominent former military officers and national security officials in whose formation Secretary of State Colin Powell played a prominent behind-the-scenes role. The brief argued that racial incidents and a general breakdown in military cohesion during the Vietnam period were attributable to the presence of large numbers of blacks in the enlisted ranks but few black officers. To prevent that problem from recurring, the military depends on modest race preferences in its ROTC programs and admission to the service academies and elsewhere.

Like The Shape of the River and the Gurin Report, the amici briefs left gaping holes in fact, in logic, and in law. Neither the corporate amici nor the military, for example, ever came close to explaining why their interests could not be satisfied from a pool of minorities graduating from schools where they were well qualified to compete rather than from a pool of academic bottom dwellers at more elite institutions. But their principal job had been to provide a safe harbor of broad institutional support for the Supreme Court in general, and Justice O’Connor in particular, and in this they succeeded.

The anti-preference forces suffered another political blow when, despite the protestations of Solicitor General Theodore Olson, President Bush decided against arguing that racial preferences in education serve no compelling need, taking the position instead that the two Michigan systems under review were the functional equivalent of illegal quotas and thus not narrowly tailored, whatever the prevailing standard. The White House recommended that interested parties examine the experience of Texas, which, it claimed, had managed through race-neutral means to maintain high levels of minority participation at the state’s flagship institutions despite the circuit court edict banning race preferences. Olson argued effectively in his appearance before the Court but without the moral clarity a more ambitious portfolio would have provided. Clearly the president had faced internal pressure. Secretary of State Powell was all but publicly on the side of Michigan. National Security adviser Condoleezza Rice offered reporters the analysis that although the president’s position in the Michigan case strikes the right balance, she also believed that race must be a factor in university admissions. A third and likely decisive voice in the internal debate belonged to White House counsel Alfredo Gonzalez, considered a possible Bush choice to fill the next Supreme Court vacancy. With Democrats threatening to filibuster nominees they consider too conservative and with a large and growing Hispanic population in Texas and other important states, Gonzalez was disinclined to become the focal point for minority fury.

The Court’s Decision

Many who argue that the Grutter decision was a lost battle rather than a lost war cite the weakness of the O’Connor majority opinion, the strong and convincing arguments of the dissenters, the continuing aversion to race preferences reflected in most polls, and the fact that the Court is likely to suffer considerable attrition in the near future, most likely during the second term of George W. Bush.

Justice O’Connor’s opinion will hardly rank as a masterpiece of American jurisprudence. She declines to decide whether Justice Powell’s decision in Bakke is binding and then appropriates every substantive determination of that decision into her own. She sprints from her former analysis of the stigmatic effects of racial entitlements. She embraces the impoverished advocacy scholarship of Bowen, Bok, and Gurin despite their having been subjected to withering counter-analyses of a far higher order of scholarship. While purporting to exert strict scrutiny over racial classifications disfavored in the law, she defers to the university’s judgment on the need for a critical mass and, even more strikingly, the dimensions of such a mass, as well as the claimed absence of any race-neutral means of achieving similar results.

The dissenters offered some cogent points. Justice Clarence Thomas wondered how Michigan could claim any compelling interest whatsoever with respect to its law school graduates since only 16 percent of them remain to practice in the state. And he warned that the principal effect of the decision will be to keep enticing black students to institutions where their performance will be well below the norm: These overmatched students take the bait, only to find that they cannot succeed in the caldron of competition.

Of the critical mass formulation, Justice Antonin Scalia jibed that the admissions statistics show it to be a sham to cover a scheme of racially proportionate admissions, while Justice Anthony Kennedy termed it a delusion used by the law school to mask its attempt to make race an automatic factor in most instances and to achieve numerical goals indistinguishable from quotas. But Justice Kennedy also endorsed Justice Powell’s formulation of the Bakke standard, and Chief Justice William Rehnquist failed to join Thomas and Scalia in rejecting the race factor altogether.

It is also worth noting that the Court had allowed 25 years of life under Bakke to pass before revisiting the issue. Quite apart from the respect for stare decisis (established precedent), the justices understand that colleges and universities throughout the country are today adjusting their admissions procedures to align themselves with the Grutter model. Two months after the Supreme Court decision, for example, Michigan itself announced the adoption of new undergraduate admission procedures, which included the individualized review of each applicant and the dropping of any bonus for race. The contribution an applicant might make toward diversity would, of course, continue to assist his chances. It would be an act approaching judicial frivolity to alter the ruling, even if one or more anti-preference justices soon joins the bench.

One must also be wary of plunging headlong into political combat against preferences. True, a majority of Americans oppose such policies in principle. And where ballot initiatives have been honestly presented, race preferences have been defeated. But as Yale law professor Peter Schuck notes in his important new book Diversity in America, preferences may be an area in which a policy’s benefits are concentrated on a relatively small but intense group while its costs are spread among a much larger but more diffuse, hard-to-organize group for which the issue is less salient. Events in Washington State and California suggest that opponents of race preferences might well prevail on a referendum only to see their advocates voted out of office as the passionate minority exacts its revenge. And, even were that not the case, it is hard to imagine that the country would now be well served by a bruising state-by-state ballot battle over racial issues.

Regarding the percent plans implemented in California (4 percent), Texas (10 percent), and Florida (20 percent), without major adjustment they would produce freshmen classes weighted down by students from failing schools who are not close to possessing the academic credentials needed to survive at elite institutions. Moreover, they apply only to state universities and have no relevance to graduate programs. Further, it has already become clear that the standard by which such programs are being judged is the ability to attract minority students in approximately the same numbers as before the abolition of race preferences. To reach that goal, one institution has decided on a more holistic approach to admissions and another has threatened to do away with SAT tests altogether. UCLA Law School provides admission advantages to students willing to specialize in critical race theory, a radical black doctrine preaching the irrelevance of the rule of law to oppressed classes. Meanwhile, Hispanic advocates urge that Hispanic students be allowed to take a Spanish proficiency exam as part of their SAT II mix. Some admission applications inquire about ways in which the applicant has experienced and overcome prejudice. These and other race-neutral contrivances serve to emphasize the fact that current race preferences that essentially amount to race-norming—judging the majority and minority candidates against others of the same race or ethnic group—produce the most academically qualified candidates of each category. The percentage plans and their race-neutral cousins will, in the end, produce something very close to the original racial and ethnic mix but without the academic efficiencies of the earlier systems.

Many race-preference opponents have in the past advocated economic affirmative action—preferences for those who are low on the socioeconomic ladder. The plans have gained few adherents because they would produce a sharp decrease in the number of blacks and Hispanics at elite schools, their places taken by low-income whites and Asian Americans with better academic credentials. In a recent paper, Anthony P. Carnevale and Stephen J. Rose of the Century Foundation conclude that adding such additional indicia of low socioeconomic status as net worth and single parentage could restore the number of preferred minorities admitted to current levels without explicitly race-conscious procedures. The credentials deficit would still be large—the beneficiaries would boast an average SAT score of only 1000—and the end result would be numerically identical to current race and ethnicity figures; but the technically race-neutral system might win the nod even from some future Court disposed to reverse the recent Michigan decision.

A Proposal for Compromise

Such political shell games ill become our legal system. The highest court in the land has issued a definitive (if narrow) ruling permitting the consideration of race in university admissions. Critical mass is the law of the land. And yet there is incentive to compromise, even for the victors. This is, after all, a volatile area of the law where past victories have proven ephemeral. True the Court has moved slowly in the education area, but, in related areas, affirmative action rulings approving employment deals and broadcast license race preferences have, in the recent past, been overturned with the speed of a brisk wind. Anti-preference ballot initiatives have prevailed in two states, and virtually every public opinion poll continues to show emphatic opposition to race preferences. Even in Michigan, despite the university’s propaganda barrage, 63 percent of those polled in one reliable survey thought preferences should go. The threat of a polarizing battle is no more pleasing to supporters of race preferences than it is to opponents.

Why not, then, experiment with a compromise system whereby colleges and universities can practice race-conscious admissions so long as each enrollment of a preferred minority is balanced with the enrollment of an otherwise rejected white or Asian American student? The approach would insulate individuals from harm and probably produce greater selectivity in the admission of preferred minorities. It is also in keeping with the tradition of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and of more recent Supreme Court holdings in the employment area, where affirmative action plans were approved only so long as majority rights were not unduly trammeled.

While subjecting the procedure to periodic review, I would not, as Justice O’Connor did, place a 25-year time limit—hard or soft—on it because I see no likelihood that the black-white academic credentials gap will narrow appreciably in the foreseeable future; if it does, race preferences will go away on their own. Furthermore, there is no benefit in encouraging a return to the race-neutral charades that have become accepted practice in the non-preference jurisdictions. My suggestion is admittedly something of an ugly duckling, but, in a pond full of ugly ducklings, this may turn out to be the swan.