- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- State & Local

- California

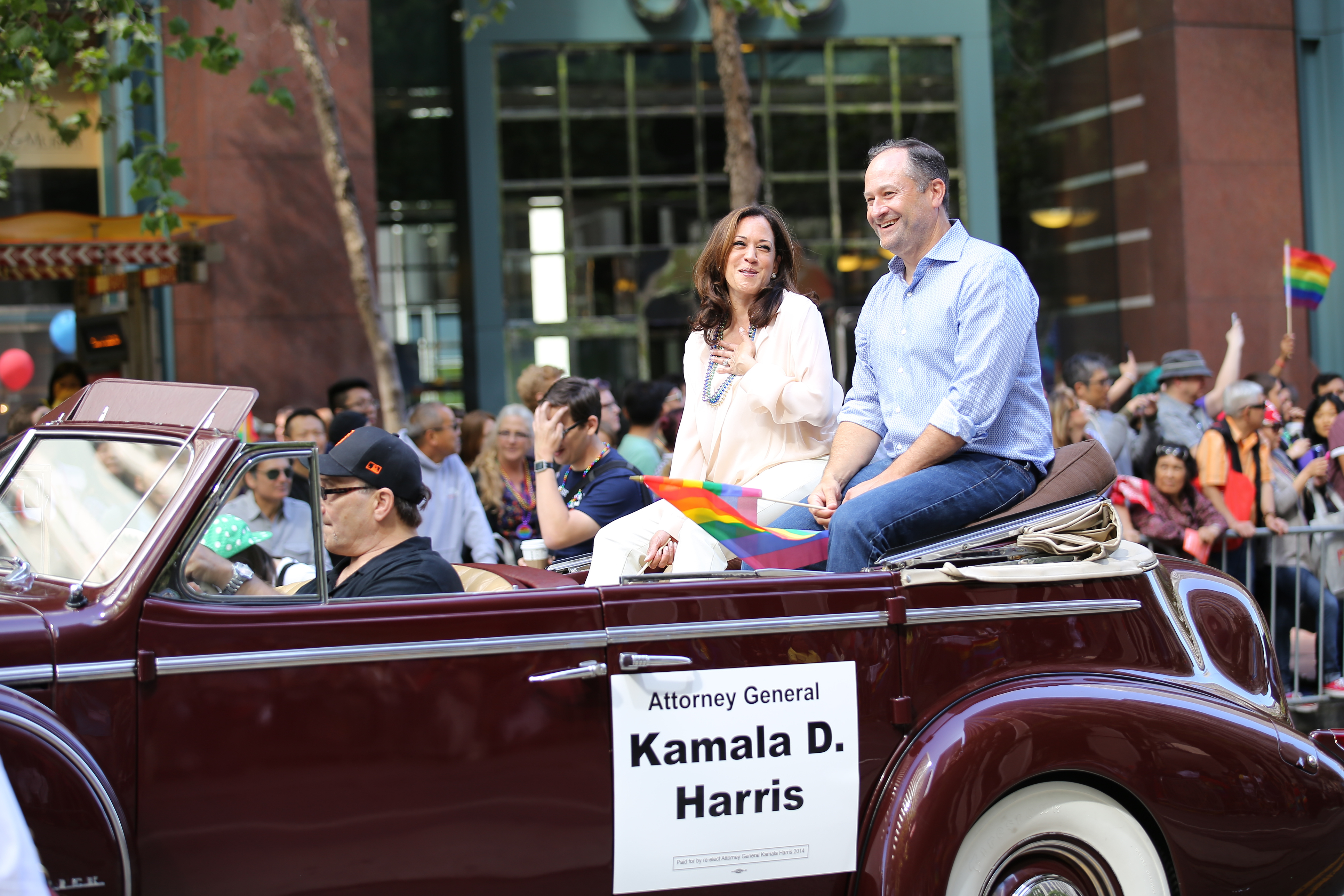

To the adage “it’s good to be king,” don’t forget the queen—in this case, California senator Kamala Harris, who may be the current ruling monarch of Democratic possibilities.

What do I mean by that?

For starters, there’s a fair-to-middling chance that Harris is part of what would be tantamount to a political coronation this summer—Joe Biden adding her to the Democratic ticket as his running mate, and making good on his promise to bring a real-life (and less profane) version of HBO’s fictional Selina Meyer to Washington.

Harris already is on most handicappers’ short lists of Biden’s possibilities. Her chances may have improved of late as: (a) former First Lady Michelle Obama seemingly has no interest in returning to the White House; (b) Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer struggles with her state’s handling of the COVID-19 crisis; and (c) former Georgia gubernatorial hopeful Stacey Abrams unsubtly campaigns for a spot on the ticket (as a rule, a presidential nominee likes to be the one doing the asking).

But what if Harris isn’t Biden’s pick, yet he still goes on to unseat President Trump in November? The first order of business for the president-elect: choosing a cabinet. In this scenario, Harris might end up on Biden’s short list for US attorney general, the California version of which Harris held prior to winning election to the US Senate.

And if that door also doesn’t open for California’s junior senator? Don’t rule out a seat on the US Supreme Court. Biden’s already pledged to name a black female to the court when the first such vacancy arises. Harris, who turns 56 in October, fits the right age demographic (Sonia Sotomayor was 55 when she joined the court in 2009). Moreover, there are but a precious few black women currently serving as appellate court judges and appointed by Democratic presidents.

And if none of those avenues are available?

There’s still the possibility of a second Harris presidential run in 2024, assuming Biden doesn’t seek another four years (he’d be a few days shy of his 82nd birthday come Election Day 2024). Another Harris campaign is assumed by most political insiders as a given should Biden lose this year’s general election.

In all, those are attractive options for a US senator with relatively little in the way of accomplishments in Washington (that may change if Democrats retake the chamber this fall). Moreover, Harris seems to have escaped with her reputation intact after a presidential run that started out with grandiose media expectations when Harris entered the race in early 2019, flew up the charts after a breakout performance in the first candidates’ debate, then crashed and burned by the year’s end with Harris quitting the race three weeks shy of Christmas and two months before the first vote in Iowa.

The funny thing about Kamala Harris’s options: should she leave the Senate prior to the end of her term in 2022, it makes for great political intrigue back in her home state.

Under California state law, Gov. Gavin Newsom would get to choose her successor, with that interim pick serving out the remainder of her term. This last happened in the Golden State in 1991, when a newly elected Pete Wilson chose the successor to the Senate seat he held prior to winning the previous fall’s governor’s race (Wilson’s choice, State Sen. John Seymour, lost to Dianne Feinstein in November 1992).

Unlike Wilson, however, Newsom likely wouldn’t choose someone who resided in the political center (during his political career, Seymour had abandoned the political right on abortion rights and offshore oil drilling, and voted to ban assault weapons and to outlaw discrimination against people with AIDS).

What Newsom would face: considerable pressure from various Democratic interest groups competing for job security.

The last elected California senator to fail at re-election, in case you’re curious: John Tunney, a one-term Democrat defeated in 1976—and the real-life inspiration for Robert Redford’s lead character in The Candidate.

California is the only state to have had both US senator positions filled by women since the dawn of the Clinton presidency. Harris was preceded by Barbara Boxer, like Feinstein a first-time winner in 1992’s “year of the woman”—‚that term sparking this response from a newly elected Maryland senator Barbara Mikulski: “Calling 1992 the Year of the Woman makes it sound like the Year of the Caribou or the Year of the Asparagus. We’re not a fad, a fancy, or a year.”

So Newsom would have to bring gender into consideration in weighing Harris’s successor. He also would have to be careful not to alienate a powerful bloc of California voters: Latinos (30% of eligible voters in the Golden State, with California accounting for roughly one-quarter of nation’s Latino electorate). A pair of Democratic Latino candidates were the runners-up in California’s 2016 and 2018 Senate contests (California’s open-primary system allows two candidates from the same party to advance to the general election). Perhaps Newsom decides to crack that barrier—and there’s an obvious choice: California secretary of state Alex Padilla.

However, even that choice might not be sufficiently “woke” for Newsom, who first burst onto the national stage in February 2004 as a recently elected, 36-year-old mayor of San Francisco who defied California state laws by issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples. Two current senators are openly LGBTQ (Wisconsin’s Tammy Baldwin and Arizona’s Kyrsten Sinema). Perhaps Newsom would add a Californian to that column.

Or maybe such Senate speculation, beginning with the premise of Harris either on a national ticket or resigning her seat for another prominent Washington role, is merely an academic exercise—one made for believers in superstition or historic coincidences.

Starting back at the beginning of the 20th century, six Californians have occupied the number-two spot on a major party’s national ticket: Hiram Johnson in 1912; Earl Warren in 1948; Richard Nixon in 1952 and 1956; Curtis LeMay in 1968; the Hoover Institution’s James Stockdale in 1992. Remove Warren and LeMay from the list and the 40-year cycle of 1912–1952–1992 suggests that California’s return to vice-presidential prominence won’t come until 2032.

Then again, what if Biden isn’t kidding and he actually does want Julia Louis-Dreyfus, a resident Californian and the Emmy award–winning actress who played the fictional “veep” on cable television? (In the HBO show, Selina Meyer’s career arc mirrors Kamala Harris’s in that her presidential bid likewise fails and she joins forces with an ex-rival.)

It’d be worth it for the lines alone. Among Selina Meyer’s better moments is the time she commits a verbal gaffe, only to admonish her aides: “I need you to make me not have said that.”

A star in her own right, with no filter between her mind and her mouth?

Sounds less like a running mate and more like the individual Biden is trying to unseat this fall.